Imagination and Its Place in the Christian School © Richard J Edlin June 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unveiled Hope

UNVEILED HOPE By Scotty Smith (This content is used with permission of Scotty Smith) UNVEILED HOPE INTRODUCTION: The Fulfillment of Our Great Hope As I write these words I am sitting at the foot of the Swiss Alps in the little fishing village of Iseltwald, just outside of Interlaken. All of my God given senses are engaged and heightened with an exhilarating intensity. Never have I seen bluer skies with a richness of hue that betrays description. I can feel the fiery warmth of the fall colors in the trees along the ridge of the Alps. And, I can taste the pure vanilla of the fresh white morning snow. Is there something that can be called too beautiful? Am I close to sensory overload? Before me is Lake Brienz whose blue-green waters seem so vast, so inviting, so absolutely calming. No tempest, just a tapestry of peacefulness that resonates with something deep in the core of my soul. It is so good to be here, right now, drinking in this astonishing vision..... for it has been a hard year, really, a hard season of life. So many changes, so many demands ..... I don't know when spiritual warfare has seemed as intense. Good friends are overwhelmed. Family members are facing loss and the adjustments forced with the advancing years. Maybe that's why this setting is just drawing me in. I feel like I am inhaling something much more vital than oxygen. The quiet of this place is so pronounced, so obvious, so centering. All I can hear is the rolling movement of a passenger train on the other side of the lake making its way to the wood carving village of Brienz. -

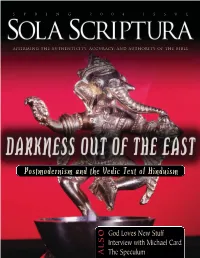

Sola Scriptura Magazine #6

SPRING 2004 ISSUE affirming the authenticity, accuracy, and authority of the bible Postmodernism and the Vedic Text of Hinduism God Loves New Stuff Interview with Michael Card ALSO The Speculum CONTENTS SOLA SCRIPTURA MAGAZINE : SPRING 2004, ISSUE 6 Founder Robert D.Van Kampen (1938-1999) Publisher Sola Scriptura Executive Director Scott R.Pierre 6 Darkness Out of the East Editor-in-Chief Dr.Dan Hayden Postmodernism and the Vedic Text of Hinduism : Our culture Managing Editor Stu Kinniburgh has taken us where we don’t want to be. The philosophical Creative Director Scott Holmgren landscape is all rather confusing. Truth is relative, reality is Contributing Writers Dr.Herbert Samworth,Dr.Dan Hayden, illusive, and ultimate destiny is anybody’s guess. We are Charles Cooper essentially a Hindu society, only we don’t call it that. We call Contributing Editor Dean Tisch it postmodernism, and we like to think of it as progress. So where did Hinduism come from, and what are its sacred Sola Scriptura magazine is a publication of Sola Scriptura,a non-profit min- texts? How do their scriptures compare with the Bible? istry that is devoted to affirming the authenticity,accuracy,and authority of the Bible—the standard for truth. BY DAN HAYDEN The pages of Sola Scriptura are designed to be evangelistic and pastoral in 14 One of God’s Favorite Words nature: evangelistic in that the magazine is dedicated to proclaiming and God Loves New Stuff : The Christian life is about being new, defending the historic gospel of Jesus Christ; pastoral in that the magazine is committed to equipping and encouraging believers through sound biblical different, and changed. -

6-SESSION BIBLE STUDY Lifeway Press® Nashville, Tennessee 1 Published by Lifeway Press® • ©2016 Lysa Terkeurst

6-SESSION BIBLE STUDY LifeWay Press® Nashville, Tennessee 1 Published by LifeWay Press® • ©2016 Lysa TerKeurst No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, except as may be expressly permitted in writing by the publisher. Requests for permission should be addressed in writing to LifeWay Press®; One LifeWay Plaza; Nashville, TN 37234-0152. ISBN 9781430053521 Item 005784578 Dewey decimal classification: 248.84 Subject heading: CHRISTIAN LIFE \ DISCIPLESHIP \ JESUS CHRIST— TEACHINGS Unless otherwise noted all Scripture quotations are from THE HOLY BIBLE, NEW INTERNATIONAL VERSION®, NIV® Copyright © 1973, 1978, 1984, 2011 by Biblica, Inc.® Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide. Scripture quotations marked ESV are from The Holy Bible, English Standard Version® (ESV®), copyright © 2001 by Crossway, a publishing ministry of Good News Publishers. Used by permission. To order additional copies of this resource, write LifeWay Church Resources Customer Service; One LifeWay Plaza; Nashville, TN 37234-0113; FAX order to 615.251.5933; call toll-free 800.458.2772; email orderentry@lifeway. com; order online at www.lifeway.com; or visit the LifeWay Christian Store serving you. Printed in the United States of America Adult Ministry Publishing, LifeWay Church Resources, One LifeWay Plaza, Nashville, TN 37234-0152 2 FINDING I AM CONTENTS 4 MEET THE AUTHOR 5 INTRODUCTION 6 ABOUT THIS STUDY SESSION 1 10 VIDEO & GROUP GUIDE 12 WEEK 1: BREAD SESSION 2 38 VIDEO & GROUP GUIDE 40 WEEK 2: LIGHT SESSION 3 66 VIDEO & GROUP GUIDE 68 WEEK 3: SHEEP GATE & SHEPHERD SESSION 4 100 VIDEO & GROUP GUIDE 102 WEEK 4: LIFE SESSION 5 132 VIDEO & GROUP GUIDE 133 WEEK 5: VINE SESSION 6 158 VIDEO & GROUP GUIDE 160 LEADER GUIDE 168 ENDNOTES 3 MEET THE AUTHOR Lysa TerKeurst is passionate about God’s Word. -

El Shaddai Notes.Pages

www.4HisKingdom.one Unwrapping El Shaddai El Shaddai, El Shaddai, El-Elyon na Adonai, Age to age You're still the same, By the power of the Name. El Shaddai, El Shaddai, Erkamka na Adonai, We will praise and lift You high, El Shaddai Through Your love and through the ram, You saved the son of Abraham; Through the power of Your hand, Turned the sea into dry land. To the outcast on her knees, You were the God who really sees, And by Your might, You set Your children free. Through the years You've made it clear, That the time of Christ was near, Though the people couldn't see What Messiah ought to be. Though Your word contained the plan, They just could not understand Your most awesome work was done Through the frailty of Your Son. El Shaddai — ‘God Almighty’ El-Elyon na Adonai — ‘God most High, O, Lord’ Erkamka na Adonai — ‘We will love You’, or more accurately ‘I love You, O Lord’ YHWH (Yahweh) is the real and personal name of God. This is the name God revealed to Moses and Israel on Mount Sinai and this is the name by which God himself said people should remember him: ‘This is my name forever; the name by which I am to be remembered generation to generation’ (Exodus 3:14-15 - NIV). The word El is used in the most general way as a designation of a deity, whether of the true God or of the false gods, even of the idols used in pagan worship. -

Leviticus Sermon Illustrations

Leviticus Sermon Illustrations Sermons Illustrations Book of Leviticus Today in the Word Copyright Moody Bible Institute. — Used by permission. All rights reserved Our Daily Bread -Copyright RBC Ministries, Grand Rapids, MI. — Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved Related Resources Multiple Commentaries and Sermons on Leviticus Leviticus Sermon Illustrations - Today in the Word Leviticus Sermon Illustrations 2 - F B Meyer Our Daily Homily Alexander Maclaren Sermons on Leviticus See also - Our Daily Bread Devotionals on Leviticus See also - Spurgeon's Devotionals on Leviticus Randy Kilgore (Our Daily Bread) has this devotional... Do I really have to read Leviticus?” A young executive asked me this in earnest as we talked about the value of spending time in reading the Bible. “The Old Testament seems so boring and difficult,” he said. Many Christians feel this way. The answer, of course, is that the Old Testament, including Leviticus, offers background and even contrasts essential to grasping the New Testament. While Isaiah challenges us to seek God (Isa 55:6), he also promises us that God’s Word accomplishes what the Lord wants it to accomplish (Isa 55:.11). Scripture is alive and powerful (Heb. 4:12), and it is useful to teach, correct, and instruct us (2 Tim. 3:16). God’s Word never returns void (Isa. 55:8-11), but sometimes it is not until later that God’s words come to mind as we need them. The Holy Spirit uses the truths we’ve stored from reading or memorization, and He helps us to apply them at just the right time. For example, Leviticus 19:10-11 speaks of business competition and even caring for the poor. -

Leviticus Commentaries & Sermons

Leviticus Commentaries & Sermons EXODUS NUMBERS LEVITICUS RESOURCES Leviticus Commentary, Sermon, Illustration OVERVIEW CHART OF BOOK OF LEVITICUS Click chart to enlarge Chart from recommended resource Jensen's Survey of the OT - used by permission Another Overview Chart of Leviticus - Charles Swindoll A third Overview Chart of Leviticus LEVITICUS: INTRODUCTORY COMMENTS LEVITICUS THE BOOK OF SANCTIFICATION AND WORSHIP Adapted and modified from C. Swindoll Leviticus 1-17 Leviticus 18-27 The Way to God The Walk with God Access Lifestyle The Approach: Offerings Practical Guidelines The Representative: Priest Chronological Observances The Laws: Cleansing Severe Consequences Physically & Spiritually Verbal promises Ritual for Worship Practical for Walking Worshipping a Holy God Living a Holy Life Location: Mt Sinai for one full year Theme: How sinful humanity can approach and worship a holy God Key Verses: Lev 17:11, 19:2, 20:7-8 Christ in Leviticus: In every sacrifice, every ritual, every feast Time: about 1446BC Key words: Holy - 90x/76v (with forms of the root for holy 152x) more than in any OT book (Lev 2:3, 10; 5:15f; 6:16f, 25-27, 29f; 7:1, 6; 8:9; 10:3, 10, 12f, 17; 11:44-45; 14:13; 16:2-4, 16f, 20, 23f, 27, 32f; 19:2, 8, 24; 20:3, 7, 26; 21:6-8, 22; 22:2-4, 6f, 10, 14-16, 32; 23:2-4, 7f, 20f, 24, 27, 35-37; 24:9; 25:12; 27:9f, 14, 21, 23, 28, 30, 32f); Atonement - 51x/45v - (Lev 1:4; 4:20, 26, 31, 35; 5:6, 10, 13, 16, 18; 6:7, 30; 7:7; 8:15, 34; 9:7; 10:17; 12:7f; 14:18-21, 29, 31, 53; 15:15, 30; 16:6, 10f, 16-18, 24, 27, 30, 32-34; 17:11; -

The Scars That Have Shaped Me: How God Meets Us in Suffering

“Vaneetha writes with creativity, biblical faithfulness, com- pelling style, and an experiential authenticity that draws other sufferers in. Here you will find both a tested life and a love for the sovereignty of a good and gracious God.” —JOHN PIPER, author of Desiring God; founder and teacher, desiringGod.org “The Scars That Have Shaped Me will make you weep and rejoice not just because it brims with authenticity and integrity, but because every page points you to the rest that is found in entrusting your life to one who is in complete control and is righteous, powerful, wise, and good in every way.” —PAUL TRIPP, pastor, author, international conference speaker “I could not put this book down, except to wipe my tears. Reading Vaneetha’s testimony of God’s kindness to her in pain was exactly what I needed; no doubt, many others will feel the same. The Scars That Have Shaped Me has helped me process my own grief and loss, and given me renewed hope to care for those in my life who suffer in various ways. Reveling in the sovereign grace of God in your pain will bolster your faith like nothing this world can offer, and Vaneetha knows how to lead you to this living water.” —GLORIA FURMAN, author of Missional Motherhood and Alive in Him “When we are suffering significantly, it’s hard to receive truth from those who haven’t been there. But Vaneetha Risner’s credibility makes us willing to lean in and listen. Her writing is built on her experience of deep pain, and in the midst of that her rugged determination to hold on to Christ.” —NANCY GUTHRIE, author of Hearing Jesus Speak into Your Sorrow “I have often wondered how Vaneetha Risner endures suffering with such amazing joy, grace, and perseverance. -

XXIX. Genesis in Biblical Perspective the Gospel of Christ from Genesis the Land, the Seed, Kings and Other Things Genesis 17 By: Dr

XXIX. Genesis in Biblical Perspective The Gospel of Christ from Genesis The Land, The Seed, Kings and Other Things Genesis 17 By: Dr. Harry Reeder In this study we will look closer at the Abrahmic covenant, how God’s promises are made and how to understand them. Let’s look at God’s Word. It’s the truth. Genesis 17:1-8 says [1] When Abram was ninety-nine years old the LORD appeared to Abram and said to him, “I am God Almighty; walk before me, and be blameless, [2] that I may make my covenant between me and you, and may multiply you greatly.” [3] Then Abram fell on his face. And God said to him, [4] “Behold, my covenant is with you, and you shall be the father of a multitude of nations. [5] No longer shall your name be called Abram, but your name shall be Abraham, for I have made you the father of a multitude of nations. [6] I will make you exceedingly fruitful, and I will make you into nations, and kings shall come from you. [7] And I will establish my covenant between me and you and your offspring after you throughout their generations for an everlasting covenant, to be God to you and to your offspring after you. [8] And I will give to you and to your offspring after you the land of your sojournings, all the land of Canaan, for an everlasting possession, and I will be their God.” The grass withers, the flower fades, the Word of our God abides forever and by His grace and mercy may His Word be preached for you. -

Wonderand Wonder Asfire

Faith HG4M0815 Interim Director, King Institute for Faith and Culture and Faith for Institute King Director, Interim Bristol,TN37620 1350 KingCollegeRoad Harris, Shannon — you might fi nd. fi might you Engaging Come into the spaces of wonder, and see what what see and wonder, of spaces the into Come and revelation, transcendence and creation may be found. be may creation and transcendence revelation, and hospitable spaces where mystery and wonder, redemption redemption wonder, and mystery where spaces hospitable re-enchantment, of recognizing and living into those those into living and recognizing of re-enchantment, poets, historians, and writers about the possibilities of of possibilities the about writers and historians, poets, with artists, theologians, philosophers, musicians, musicians, philosophers, theologians, artists, with Culture encounters thoughtful into us brings Culture and Faith The 2015–2016 program of the King Institute for for Institute King the of program 2015–2016 The of complacency, whispers us out of apathy. apathy. of out us whispers complacency, of learning to love, to be moved to awe. Wonder jolts us out out us jolts Wonder awe. to moved be to love, to learning us. For it is in being attentive that we learn to love, and in in and love, to learn we that attentive being in is it For us. rain, as Mary Oliver, that poet of awareness, pleads with with pleads awareness, of poet that Oliver, Mary as rain, how God moves among us. Notice the clear pebbles of the the of pebbles clear the Notice us. among moves God how 2016 – 2015 And later, we might be awed by the spaces of wonder and and wonder of spaces the by awed be might we later, And our attention in these thin places, present in grief and joy. -

2011 Media Idea Book

media idea book Bringing the Stories to You. Starting the Discussions for You. 2011-2012 The InterVarsity Press publicists would like to present to you our annual Media Idea Book! Angles, talking points and author highlights have been included for our most recent topical books. We hope you find this useful for articles and broadcasts, with our titles and authors organized into the relevant and timely categories listed below: Spiritual Formation Current Events Cultural Critique Relationships Sexuality African American Interest Biblical Interpretation Professional Science If you don’t find the topic you are looking for in the Media Idea Book, please feel free to contact one of us, and we’ll be happy to assist you. Be sure to visit the recently redesigned Media Idea Center (ivpress.com/media) for press kits and information about our most recent titles. While there you can check out “InterVarsity Press in the News,” our Facebook page devoted to bringing you our most timely and newsworthy happenings. You can also catch up on our latest news by following us on twitter @ivpress. Let us know if you would like to see review copies or if you want to set up interviews with any of our authors. Suanne Camfield, Print Publicist – IVP Books, [email protected], 630.734.4012 Alisse Wissman, Print Publicist – IVP Academic, [email protected], 630.734.4059 Krista Carnet, Broadcast Publicist, [email protected], 630.734.4013 Adrianna Wright, Online Publicist, [email protected], 630.734.4096 spiritual formation ivpress.com/media RICHAR D J. FOSTER Foster opens the door to meditation Author of Celebration of Discipline Angle and Talking Points Sanctuary of the Soul Distraction is one of the deepest cultural problems we face today. -

Directory of Contemporary Worship Musicians 3

Directory of Contemporary Worship Musicians Copyright 2011 by David W. Cloud ISBN 978-1-58318-226-0 Tis edition August, 2020 Tis book is published for free distribution in eBook format. It is available in PDF, Mobi (Kindle), and ePub formats from the Way of Life web site. See the Free Book tab at www.wayofife.org. We do not allow distribution of our free eBooks from other web sites. Published by Way of Life Literature PO Box 610368, Port Huron, MI 48061 866-295-4143 (toll free) - [email protected] www.wayofife.org Canada: Bethel Baptist Church 4212 Campbell St. N., London Ont. N6P 1A6 519-652-2619 (voice) - 519-652-0056 (fax) [email protected] Table of Contents Introduction ...............................................................................9 Directory of Contemporary Worship Musicians ................12 7eventh Time Down ................................................................12 Abandon ...................................................................................13 Alpha Course ............................................................................15 Amerson, Steve ........................................................................17 Arends, Carolyn .......................................................................17 Assad, Audrey ..........................................................................19 Audio Adrenaline ....................................................................20 Baloche, Paul ............................................................................24 Beatles -

A Biblical-Theological Survey of Moses, Prophets and the Writings Latter Prophets: Introduction to the Prophets & Prophetic Word Rev

Cycle 3: Theological Survey A Biblical-Theological Survey of Moses, Prophets and the Writings Latter Prophets: Introduction to the Prophets & Prophetic Word Rev. Charles R. Biggs, Th.M. February – March 2019 INTRODUCTION TO THE PROPHETS Michael Card, ‘They Shall Know' I will speak This is salvation I will wait This is their great hope and mine I will send prophets among them He will come That they might hear My own Son That they might see A Word faithful hearts can't help hearing And understand how much I love them And by His death With His last breath Then they will know that I am Father A Father's forgiveness comes flowing Then they will know I am Lord They'll walk with Me Then they will know And be My people That I am Savior I'll walk with them as their God I am Redeemer and Friend As their God Immanuel, The God who is with them The God who gives all He can I will strike He is salvation I will scourge He is the kingdom And carry out vengeance upon them To know Him is paradise But I will heal the wound that I make Then they will know that I am Father And tenderly take them back to me Then they will know I am Lord I am Lord. Then they will know that I am Father Then they will know I am Lord They'll walk with Me And be My people I'll walk with them as their God This is heaven Songwriters: Michael Card / Scott M.