The Local Historian

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The History of Policing 97

THE HISTORY 4 OF POLICING distribute or post, copy, not Do Copyright ©2015 by SAGE Publications, Inc. This work may not be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means without express written permission of the publisher. “The myth of the unchanging police “You never can tell what a man is able dominates much of our thinking about to do, but even though I recommend the American police. In both popular ten, and nine of them may disappoint discourse and academic scholarship one me and fail, the tenth one may surprise continually encounters references to the me. That percentage is good enough for ‘tradition-bound’ police who are resistant me, because it is in developing people to change. Nothing could be further from that we make real progress in our own the truth. The history of the American society.” police over the past one hundred years is —August Vollmer (n.d.) a story of drastic, if not radical change.” —Samuel Walker (1977) distribute INTRODUCTION: POLICING LEARNING OBJECTIVES or After finishing this chapter, you should be able to: AS A DYNAMIC ENTITY Policing as we know it today is relatively new. 4.1 Summarize the influence of early The notion of a professional uniformed police officer English policing on policing and the receiving specialized training on the law, weapon use, increasing professionalization of policing and self-defense is taken for granted. In fact, polic- in the United States over time. post,ing has evolved from a system in which officers ini- tially were appointed by friends, given no training, 4.2 Identify how the nature of policing in the provided power to arrest without warrants, engaged United States has changed over time. -

Constables Accounts

Worfield Constables Accounts 1590-1675 this series is P314/M constables accounts [P314/M/1/2] 1590 Robert and Roger … constables for carrying a load of wood for the coronation 15d for bringing a poor woman to Claverley 3d for bringing a poor woman to Stockton 3d for bringing a … to Bridgnorth and for his diet 3d for bringing a poor woman on Syverne 3d for going 2 times with hue and cry to Bridgnorth 6d laid out at the muster at Shifnal 4s 8d paid at Bridgnorth to the justices for one soldier, conduct money 41s for mending a calinder flaske and tuchbox 12d for a girdle 6d for one locker and two chapes for daggers 6d for 2 sword girdles 2s 4d for the charges of a prest soldier 16d for the carrying of furniture to Bridgnorth and expenses there for mending 2 girdles 3d for bringing a lame man in a cart to Stockton 6d for wages of soldier and expenses of the training 2 days 16d for a sheffe of arrows for a bow for a quiver [ page torn] [next page] … laid out to a soldier who went into Ireland 36s for his diet and carrying his furniture to Shrewsbury and for a ?girdle 2s 11d for mending a flask, tuchboxe and headpiece 4d for a flask and matchbox 4s 4d for match and powder 8d for other charges at Bridgnorth14d for bringing a man to Pattingham 6d for keeping to boys to Bridgnorth as prisoners for the space of 3 days 8d for bringing them to Bridgnorth 2d for bringing them to Shrewsbury 3s 4d laid out at Bewdley concerning carriage of the councell stuff 21s 3d for ten calyvers and furniture to them 33s laid out at the subsidy at Bridgnorth 20d for -

Harvest Edge, Wyre Common Offers Over Neen Savage, Nr Cleobury Mortimer, DY14 8HG £399,999 Harvest Edge, Wyre Common

Harvest Edge, Wyre Common Offers over Neen Savage, Nr Cleobury Mortimer, DY14 8HG £399,999 Harvest Edge, Wyre Common Neen Savage, Nr Cleobury Situated on the edge of Cleobury Mortimer this four bedroom bungalow offers versatile accommodation for any family with outstanding and far reaching views across the valley, including the famous crooked spire of St Marys Church. From the opposite direction when driving through the town of Cleobury Mortimer the property can be clearly seen on the horizon. • Four bedroom bungalow • Outstanding far reaching views • Located in the Parish Neen Savage • Excellent schooling • Parking for five Plus cars • Secluded spot Directions From Ludlow head over Clee Hill and continue on that road until you come to the small town of Cleobury Mortimer, continue through the village and take the left hand turn towards Bridgnorth and Neen Savage and head towards golf course, the property is located on the right hand-side diagonally opposite the entrance to the Golf course. Introduction Do you have a property to sell or rent? The property benefits from a master bedroom with the scope for a potential En We offer a free market appraisal and Suite currently being used as a dressing room, a double guest bedroom with En according to Rightmove we are the number Suite, two further bedrooms, a hobbies room, drying room and a family bathroom. one agent across our region for sales and The living space consists of a kitchen which flows into the dining room with dual lets agreed* aspect windows with views out, a spacious lounge, with double doors out to a decking BBQ area with garden surrounding and study. -

Urban Policing in Early Victorian England, 183586: a Reappraisal

Urban Policing in Earlv Victorian J England, 1835-86: a reap p r ai sa1 Roger Swift Chester College of Higher Education hirty years have now elapsed since the publication of Jenifer Hart's seminal study of early Victorian policing.' Subsequently, the T historical debate on the development of policing in the towns and cities of early Victorian England has focused largely on three inter-related themes, namely the circumstances which prompted the advent of the 'new police', the levels of efficiency which the reformed forces attained, and the degree of public acceptability which they received. Police historians have been divided on these issues. Some, including Charles Reith, Sir Leon Radzinowicz, T. Critchley, and J.J. Tobias, have viewed provincial police reform largely in terms of the Benthamite march of progress, whereby the unreformed system was swept away by a centralised and efficient system for the prevention and detection of crime which owed much to the Metropolitan model established by Peel in 1829 and which soon received a general measure of public support and co-operation.' Others, including Robert Storch, David Philips and Tony Donajgrodzki, have argued that police reform was but one strand in the extension of control over working-class society and that the priorities, organisation and methods of ' J. Hart, 'The Reform of the Borough Police, 1835-56: E/nglish] Hlisrorical] Rleview], 1955, cxx, 411-27; see also J. Hart, 'The County and Borough Policc Act, 1856, Public Administration, 1956, 34. ' See, for example, C. Reith, A New Study ofPolice Hirfory (London, 1956); L. Radzinowin. A History of' English Criminal Law and its Administrution from 17.50 (4 vols, London, 1948-68); T.A. -

Northumberland and Durham Family History Society Unwanted

Northumberland and Durham Family History Society baptism birth marriage No Gsurname Gforename Bsurname Bforename dayMonth year place death No Bsurname Bforename Gsurname Gforename dayMonth year place all No surname forename dayMonth year place Marriage 933ABBOT Mary ROBINSON James 18Oct1851 Windermere Westmorland Marriage 588ABBOT William HADAWAY Ann 25 Jul1869 Tynemouth Marriage 935ABBOTT Edwin NESS Sarah Jane 20 Jul1882 Wallsend Parrish Church Northumbrland Marriage1561ABBS Maria FORDER James 21May1861 Brooke, Norfolk Marriage 1442 ABELL Thirza GUTTERIDGE Amos 3 Aug 1874 Eston Yorks Death 229 ADAM Ellen 9 Feb 1967 Newcastle upon Tyne Death 406 ADAMS Matilda 11 Oct 1931 Lanchester Co Durham Marriage 2326ADAMS Sarah Elizabeth SOMERSET Ernest Edward 26 Dec 1901 Heaton, Newcastle upon Tyne Marriage1768ADAMS Thomas BORTON Mary 16Oct1849 Coughton Northampton Death 1556 ADAMS Thomas 15 Jan 1908 Brackley, Norhants,Oxford Bucks Birth 3605 ADAMS Sarah Elizabeth 18 May 1876 Stockton Co Durham Marriage 568 ADAMSON Annabell HADAWAY Thomas William 30 Sep 1885 Tynemouth Death 1999 ADAMSON Bryan 13 Aug 1972 Newcastle upon Tyne Birth 835 ADAMSON Constance 18 Oct 1850 Tynemouth Birth 3289ADAMSON Emma Jane 19Jun 1867Hamsterley Co Durham Marriage 556 ADAMSON James Frederick TATE Annabell 6 Oct 1861 Tynemouth Marriage1292ADAMSON Jane HARTBURN John 2Sep1839 Stockton & Sedgefield Co Durham Birth 3654 ADAMSON Julie Kristina 16 Dec 1971 Tynemouth, Northumberland Marriage 2357ADAMSON June PORTER William Sidney 1May 1980 North Tyneside East Death 747 ADAMSON -

Pounds Text Make-Up

A HISTORY OF THE ENGLISH PARISH f v N. J. G. POUNDS The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge , UK http: //www.cup.cam.ac.uk West th Street, New York –, USA http://www.cup.org Stamford Road, Oakleigh, Melbourne , Australia © N. J. G. Pounds This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typeset in Fournier MT /.pt in QuarkXPress™ [] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress cataloguing in publication data Pounds, Norman John Greville. A history of the English parish: the culture of religion from Augustine to Victoria / N. J. G. Pounds. p. cm. Includes index. . Parishes – England – History. Christianity and culture – England – History. England – Church history. Title. Ј.Ј – dc – hardback f v CONTENTS List of illustrations page viii Preface xiii List of abbreviations xv Church and parish Rectors and vicars: from Gratian to the Reformation The parish, its bounds and its division The urban parish The parish and its servants The economics of the parish The parish and the community The parish and the church courts: a mirror of society The parish church, popular culture and the Reformation The parish: its church and churchyard The fabric of the church: the priest’s church The people’s church: the nave and the laity Notes Index vii f v ILLUSTRATIONS The traditional English counties xxvi . -

The London Gazette. Fop &Ut|Jortt£V

flllUlf). 26276. 2079 The London Gazette. fop &ut|jortt£v . FRIDAY, APRIL 8, 1892. Lord Chamberlain's Office, St. James's Palace, the Lord Chamberlain at the Levee, in order that March'SO, 1892. there may be no difficulty in announcing them to "VpOTlCK is hereby given, that Her Majesty's His <Royal Highness. -L T! Birthday will be kept on Wednesday, the LATHOM, 25th of May next. Lord Chamberlain. Lord Chamberlain's Office, St. James's Palace, Lord Chamberlain's Office, St. James's Palace, April 4, 1892. March 29, 1892. OTICE is hereby given, that The Queen OTICE is hereby given, that— N will hold Drawing Rooms at Buckingham N His Royal Highness The Duke of Edin- Palace, on Monday, the 16th, and Wednesday, burgh will, by command of The Queen, hold a the 18th of May next, at three o'clock. Levee, at St. James's Palace, on behalf of Her Majesty, on Thursday, the 5th of May next, at REGULATIONS two o'clock ; TO BE OBSERVED AT THE QUEEN'S DRAWING His Royal Highness The Duke of Connaught ROOMS. will, by command of The Queen, also hold a By Her Majesty's Command, Levee at St. James's Palace, on behalf of Her The Ladies who propose to attend Her Majesty, on Thursday, the 12th of May next, at Majesty's Drawing Rooms are requested to bring two o'clock. with them to the Drawing Room two large cards, It is The Queen's pleasure that Presentations to with their names clearly written thereon, one to be Their Royal Highnesses at these Levees shall be left with The Queen's Page, in Attendance, and considered as equivalent to Presentations to Her the other to be delivered to the Lord Chamberlain, Majesty. -

The Old-Timer

The Old-Timer produced by www.prewarboxing.co.uk Number 1. August 2007 Sid Shields (Glasgow) – active 1911-22 This is the first issue of magazine will concentrate draw equally heavily on this The Old-Timer and it is my instead upon the lesser material in The Old-Timer. intention to produce three lights, the fighters who or four such issues per year. were idols and heroes My prewarboxing website The main purpose of the within the towns and cities was launched in 2003 and magazine is to present that produced them and who since that date I have historical information about were the backbone of the directly helped over one the many thousands of sport but who are now hundred families to learn professional boxers who almost completely more about their boxing were active between 1900 forgotten. There are many ancestors and frequently and 1950. The great thousands of these men and they have helped me to majority of these boxers are if I can do something to learn a lot more about the now dead and I would like preserve the memory of a personal lives of these to do something to ensure few of them then this boxers. One of the most that they, and their magazine will be useful aspects of this exploits, are not forgotten. worthwhile. magazine will be to I hope that in doing so I amalgamate boxing history will produce an interesting By far the most valuable with family history so that and informative magazine. resource available to the the articles and features The Old-Timer will draw modern boxing historian is contained within are made heavily on the many Boxing News magazine more interesting. -

An Archaeological Analysis of Anglo-Saxon Shropshire A.D. 600 – 1066: with a Catalogue of Artefacts

An Archaeological Analysis of Anglo-Saxon Shropshire A.D. 600 – 1066: With a catalogue of artefacts By Esme Nadine Hookway A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of MRes Classics, Ancient History and Archaeology College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham March 2015 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract The Anglo-Saxon period spanned over 600 years, beginning in the fifth century with migrations into the Roman province of Britannia by peoples’ from the Continent, witnessing the arrival of Scandinavian raiders and settlers from the ninth century and ending with the Norman Conquest of a unified England in 1066. This was a period of immense cultural, political, economic and religious change. The archaeological evidence for this period is however sparse in comparison with the preceding Roman period and the following medieval period. This is particularly apparent in regions of western England, and our understanding of Shropshire, a county with a notable lack of Anglo-Saxon archaeological or historical evidence, remains obscure. This research aims to enhance our understanding of the Anglo-Saxon period in Shropshire by combining multiple sources of evidence, including the growing body of artefacts recorded by the Portable Antiquity Scheme, to produce an over-view of Shropshire during the Anglo-Saxon period. -

The Times , 1992, UK, English

ES MONDAY FEBRUARY 3 1992 JAMES GRAY Minister backs wider choice Abductor linked TODAY IN THE TIMES to food GETTING AWAY poison threats m&K- m** - By Craig Seton &*+ ~ .. * *#:- * POLICE are investigating whether the kidnapper of mi=T.r^ Europe, Asia, grammar school Stephanie Slater could be a America., faffed “consumer terrorist” MM •> wherever the who tried to exton money by in By threatening world want to 4tew John O leary, higher education correspondent to contaminate you supermarket food. * a«~ -*r go, a friend can THE Conservative party schools could reappear would lead to the re-emer- Tom Cook, head of a joint 9k -r- fly free and stay sprung a pre-election sur- throughout the counby, as gence of grammar schools: police investigation into the fa> t*C*. free with the six prise yesterday by signal- long as there were not too Jack Straw. Labour's educa- abduction of Miss Slater and Times privilege ling the return of gram- mapy in each area. tion spokesman, said: “The the murder last year of Julie He has always opposed a Conservatives are paralysed Dan, said yesterday tokens being mar schools as part of a that pos- return to the mix ofgrammar on this issue because they sible links were being exam- more diverse state educa- published earn * and secondary, modern know that the remtraduction ' ined with seven or eight faffed tion system. I’ day this week. ..'.SV* ' schools created by the 1944 of selection at 11 is not want- d> attempts at extortion involv- In a significant shift of l Collect the second Education Act, arid he reiter- ed by the majority of parents. -

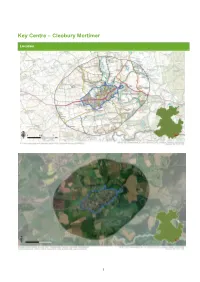

Cleobury Mortimer

Key Centre – Cleobury Mortimer Location 1 Summary of Settlement Study Area and Location Introduction Cleobury Mortimer, in south east Shropshire has been identified as a Key Centre within the Shropshire Pre-Submission Draft Local Plan (2020). This Green Infrastructure Strategy has defined the study area as a 1km buffer around this settlement. Cleobury Mortimer, is a rural market town located on the western side of the River Rea, just over 4km east of the Clee Hills and 3km west of the Wyre Forest. It is around 17km to the east of Ludlow and a similar distance to the west of Kidderminster. The town has a population of just over 3,000. And around 1,306 dwellings. Development context Existing development allocations in the town are set out in the SAMDev (2015)1, however the Shropshire Local Plan is currently being reviewed. The Pre-Submission Draft Local Plan (2020) proposes other sites, which are not yet adopted. The Shropshire Pre-Submission Draft Local Plan (2020) outlines that Cleobury Mortimer Town Council are developing a Neighbourhood Plan and so it is intended that Shropshire Council will work closely with the Neighbourhood Plan Steering Group to provide an overall housing guideline for the town, with the Neighbourhood Plan determining how growth should be managed and potentially identifying a development boundary for the town and any specific allocations. The Plan Review identifies that the town has a remaining residential requirement of approximately 120 dwellings and 1ha of employment land to be delivered over the Plan period up to 2038. The locations of potential allocations to deliver these requirements are to be determined by the Neighbourhood Plan. -

Round 9 2021 Row Volume 2 · Issue 9

The FRONTROUND 9 2021 ROW VOLUME 2 · ISSUE 9 FROM THE START TAKE A TOUR OF RUGBY LEAGUE'S HISTORIC SYDNEY BIRTHPLACES INSIDE: NRL Round 9 program with squad lists, previews & head to head stats, Round 8 reviewed LEAGUEUNLIMITED.COM AUSTRALIA’S LEADING INDEPENDENT RUGBY LEAGUE WEBSITE THERE IS NO OFF-SEASON 2 | LEAGUEUNLIMITED.COM | THE FRONT ROW | VOL 2 ISSUE 9 What’s inside From the editor THE FRONT ROW - VOL 2 ISSUE 9 Tim Costello From the editor 3 A fascinating piece from our historian Andrew Ferguson in this A rugby league history tour of Sydney 4-5 week's issue - a tour of some of Sydney's key historic rugby league locations. Birthplaces of clubs, venues and artefacts NRL Ladder, Stats Leaders. Player Birthdays 6 feature in a wide-range trip across the nation's first city. GAME DAY · NRL Round 9 7-23 On the field and this weekend sees two important LU Team Tips 7 commemorations - on Saturday at Campbelltown the Wests THU South Sydney v Melbourne 8-9 Tigers will done a Magpies-style jersey to honour the life of FRI Penrith v Cronulla 10-11 Tommy Raudonikis following his passing last month. The match day will also feature a Ron Massey Cup and Women's Premiership Parramatta v Sydney Roosters 12-13 double header as curtain raisers, with the Magpies facing Glebe SAT Canberra v Newcastle 14-15 in both matches. Wests Tigers v Gold Coast 16-17 Kogarah will play host to the other throwback with the St George North Queensland v Brisbane 18-19 Illawarra club celebrating the 100th anniversary of St George RLFC.