The Crown Commercial Service

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UK Open Government National Action Plan 2016-18

UK Open Government National Action Plan 2016-18 May 2016 © Crown copyright 2016 You may re-use this information (not including logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence. To view this licence, visit www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/ or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email [email protected] Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us at [email protected] This publication is available for download at http://www.gov.uk/government/publications/uk- open-government-national-action-plan-2016-18 Foreword by the Minister for the Cabinet Office and Paymaster General This government is determined to deliver on its fundamentally changing how power is manifesto commitment to continue to be the distributed and the scale and speed of human most transparent government in the world. This connection. These changes don’t just make it is an ambitious task - but we are building on a possible to open-up as never before - they strong base. I am proud of our global demand it. reputation as a pioneer and leader on open government, and I am determined that we There is much to be proud of in this, our third continue to stretch ourselves to stay at the Open Government Partnership National Action forefront of this exciting agenda. Plan: It is staggering to think how far we have • unprecedented visibility on how already come. Until the late 18th century it was government spends money illegal to report on parliamentary proceedings. -

Digital Public Administration Factsheet 2020 United Kingdom

Digital Public Administration factsheet 2020 United Kingdom ISA2 Digital Public Administration Factsheets – United Kingdom Table of Contents 1 Country Profile ............................................................................................. 4 2 Digital Public Administration Highlights ........................................................... 9 3 Digital Public Administration Political Communications .....................................12 4 Digital Public Administration Legislation .........................................................23 5 Digital Public Administration Governance .......................................................27 6 Digital Public Administration Infrastructure .....................................................35 7 Cross-border Digital Public Administration Services for Citizens and Businesses ..44 2 Digital Public Administration Factsheets – United Kingdom Country 1 Profile 3 Digital Public Administration Factsheets – United Kingdom 1 Country Profile 1.1 Basic data Population: 66 647 112 inhabitants (2019) GDP at market prices: 2 523 312.5 million Euros (2019) GDP per inhabitant in PPS (Purchasing Power Standard EU 27=100): 105 (2019) GDP growth rate: 1.4 % (2019) Inflation rate: 1.8 % (2019) Unemployment rate: 3.8 % (2019) General government gross debt (Percentage of GDP): 85.4 % (2019) General government deficit/surplus (Percentage of GDP): -2.1 % (2019) Area: 247 763 km2 Capital city: London Official EU language: English Currency: GBP Source: Eurostat (last update: 26 June 2020) 4 Digital -

Ministerial Departments CABINET OFFICE July 2015

LIST OF MINISTERIAL RESPONSIBILITIES Including Executive Agencies and Non- Ministerial Departments CABINET OFFICE July 2015 LIST OF MINISTERIAL RESPONSIBILITIES INCLUDING EXECUTIVE AGENCIES AND NON MINISTERIAL DEPARTMENTS CONTENTS Page Part I List of Cabinet Ministers 2 Part II Alphabetical List of Ministers 4 Part III Ministerial Departments and Responsibilities 8 Part IV Executive Agencies 64 Part V Non-Ministerial Departments 76 Part VI Government Whips in the House of Commons and House of Lords 84 Part VII Government Spokespersons in the House of Lords 85 Part VIII Index 87 Information contained in this document can also be found at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/government-ministers-and-responsibilities Further copies of this document can be obtained from: Cabinet Office Room 208 70 Whitehall London SW1A 2AS Or send your request via email to: [email protected] 1 I - LIST OF CABINET MINISTERS The Rt Hon David Cameron MP Prime Minister, First Lord of the Treasury and Minister for the Civil Service The Rt Hon George Osborne MP First Secretary of State and Chancellor of the Exchequer The Rt Hon Theresa May MP Secretary of State for the Home Department The Rt Hon Philip Hammond MP Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs The Rt Hon Michael Gove MP Lord Chancellor, Secretary of State for Justice The Rt Hon Michael Fallon MP Secretary of State for Defence The Rt Hon Iain Duncan Smith MP Secretary of State for Work and Pensions The Rt Hon Jeremy Hunt MP Secretary of State for Health The -

Framework Agreement for the Supply of Non Medical Non Clinical (NMNC)

Crown Commercial Service ___________________________________________________________________ Framework Agreement for the Supply of Non Medical Non Clinical (NMNC) temporary and fixed term staff RM971 ___________________________________________________________________ Crown Commercial Service The Supply of Non Medical Non Clinical Temporary and Fixed Term Staff RM971 Framework Agreement Attachment 5 1 DATED [dd/mm/yyyy] CROWN COMMERCIAL SERVICE and [SUPPLIER NAME] THE SUPPLY OF NON MEDICAL NON CLINICAL (NMNC) TEMPORARY AND FIXED TERM STAFF FRAMEWORK AGREEMENT (Agreement Ref: RM971) Crown Commercial Service The Supply of Non Medical Non Clinical Temporary and Fixed Term Staff RM971 Framework Agreement Attachment 5 2 [PRE-FRAMEWORK AGREEMENT CONCLUSION GUIDANCE NOTE: 1. Attention is drawn to the various guidance notes to the Authority highlighted in green, and the square brackets and information/text to complete/settle therein highlighted in yellow in this document. 2. Before this Framework Agreement is signed, the parties should ensure that they have read the guidance notes, taken any actions necessary as indicated in the guidance notes and/or square brackets and then delete the guidance notes and the square brackets (and the text included in the square brackets if not used) from this document. 3. The Authority and the supplier will agree between them where the supplier needs to provide certain information to enable the Authority to complete this task. 4. The guidance notes are not exhaustive but have been included to assist the parties in completing any information required with sufficient detail.] Crown Commercial Service The Supply of Non Medical Non Clinical Temporary and Fixed Term Staff RM971 Framework Agreement Attachment 5 3 TABLE OF CONTENT A. -

Contract Management Handbook

The University of Texas at El Paso CONTRACT MANAGEMENT HANDBOOK The University of Texas at El Paso Page 1 Contract Management Handbook TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter 1 Introduction .......................................................................................................... 4 1.1 Purpose 1.2 Definitions 1.3 Acronyms 1.4 Training for Purchasing Personnel and Contract Managers 1.5 Ethics Standards and Policies 1.6 Conflict of Interest 1.7 Ethics Requirements from Senate Bill 20 (2015) 1.8 Disclosure of Interested Parties Chapter 2 Planning .............................................................................................................. 22 2.1 Contract Management Team 2.2 Determining Competitive Procurement Method 2.3 Planning for Contract Content 2.4 Information Security; Access to Electronic and Information Resources 2.5 Record Retention Chapter 3 Preparing the Solicitation .................................................................................... 47 3.1 Historically Underutilized Business (HUB) Requirements 3.2 Contract Term 3.3 Background Information 3.4 Proposal Submission Requirements 3.5 Evaluation of Proposals 3.6 Solicitation Requirements 3.7 Payment Types Chapter 4 Publication of the Solicitation .............................................................................. 65 4.1 Advertising 4.2 Solicitation Announcements 4.3 Communication with Respondents 4.4 Written Questions 4.5 Pre-Proposal Conferences 4.6 Solicitation Submission and Opening Chapter 5 Evaluation and Award ........................................................................................ -

Cabinet Office | Annual Report and Account 2019-20

Annual Report and Accounts 2019-20 HC 607 DIRECTORS’ REPORT Cabinet Office | Annual Report and Account 2019-20 ANNUAL REPORT AND ACCOUNTS 1 2019-20 (for period ended 31 March 2020) Accounts presented to the House of Commons pursuant to Section 6 (4) of the Government Resources and Accounts Act 2000 Annual Report presented to the House of Commons by Command of Her Majesty Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed on 21 July 2020 HC 607 D Cabinet Office | Annual Report and Account 2019-20 This is part of a series of Departmental publications which, along with the Main Estimates 2020-21 and the document Public Expenditure: Statistical Analyses 2019, present the Government’s outturn for 2019-20 and planned expenditure for 2020-21. 1 © Crown copyright 2020 This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-Government-licence/version/3 Where we have identified any third-party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. This publication is available at: www.gov.uk/official-documents Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us at: [email protected] ISBN – 978-1-5286-2083-3 CCS – CCS0620706748 07/20 Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fibre content minimum. Printed in the UK by the APS Group on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office D Cabinet Office | Annual Report and Account 2019-20 Contents 3 D Cabinet Office | Annual Report and Account 2019-20 Cover Photo 4 70 Whitehall DIRECTORS’ REPORT Cabinet Office | Annual Report and Account 2019-20 DIRECTORS’ REPORT 5 D Cabinet Office | Annual Report and Account 2019-20 I want to put on record here my admiration for Cabinet Office’s Foreword resourceful and public-spirited staff, and their dedication to mitigating the effects of coronavirus. -

Contract Management Program Flyer

Division of Continuing Education Contract Management Certificate Program: Online Focusing on core competencies recognized by the National Contract Management Association, program coursework addresses the most up-to-date 446,942 information available in the procurement and contracting fields – whether JOBS (2018) commercial, government or international. Students will develop a solid under- standing of the contracting process and key elements of procurement and acquisition, including contract formation, negotiation, financial analysis and risk management. Students will also explore new business areas such as global out- 9.5% sourcing, international contracting, doing business with the federal government PROJECTED GROWTH and building strategic alliances. (2018-2028) WHO SHOULD ATTEND: This program is for people working in large or small organizations, government and $ $ commercial entities, or as entrepreneurs. It will benefit those working as contract 75k- 140k administrators, subcontractors, procurement managers, project managers, quality ANNUAL SALARY assurance personnel, and others who wish to enter the field or advance their career. (25TH-75TH PERCENTILE) PROGRAM BENEFITS: • Gain an understanding of the contract life cycle, sub-contracting, outsourcing, CERTIFICATE PROGRAM: developing strategic alliances, negotiation, financial analysis, and implementation. ONLINE • Explore the components and processes of commercial and government contracting. • Expand your awareness of the legal, risk, and ethical issues related to contracting and -

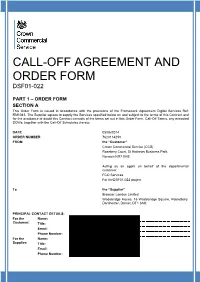

CALL-OFF AGREEMENT and ORDER FORM V3

CALL-OFF AGREEMENT AND ORDER FORM DSF01-022 PART 1 – ORDER FORM SECTION A This Order Form is issued in accordance with the provisions of the Framework Agreement Digital Services Ref: RM1043. The Supplier agrees to supply the Services specified below on and subject to the terms of this Contract and for the avoidance of doubt this Contract consists of the terms set out in this Order Form, Call-Off Terms, any executed SOWs, together with the Call-Off Schedules thereto. DATE 05/06/2014 ORDER NUMBER 7620114259 FROM the “Customer” Crown Commercial Service (CCS) Rosebery Court, St Andrews Business Park, Norwich NR7 0HS Acting as an agent on behalf of the departmental customer: FCO Services For theDSF01-022 project To the “Supplier” Browser London Limited Wadebridge House, 16 Wadebridge Square, Poundbury, Dorchester, Dorset, DT1 3AQ PRINCIPAL CONTACT DETAILS: For the Name: Claire Perry Customer: Title: Marketing and Communications Manager Email: [email protected] Phone Number: 01908 745338 For the Name: Julian Morency Supplier: Title: Managing Director Email: [email protected] Phone Number: 020 3355 6891 DSF01-022 FRAMEWORK SCHEDULE 3 - CALL-OFF TERMS Digital Services Framework Agreement – RM1043 SECTION B 1. TERM 1.1 Commencement Date: 23/06/14 2. CUSTOMER CORE CONTRACTUAL REQUIREMENTS 2.1 Services required For the provision of transition and redevelopment of website under the DSF01-022 project and as shown within Schedule 3 and Schedule 7 2.2 Warranty Period 90 Days 2.3 Location/Premises FCO Services, Hanslope Park, Milton Keynes, MK19 7BH 3. SUPPLIER’S INFORMATION 3.1 Supplier Software and Licences None 3.2 Commercially Sensitive Information None 4. -

Ministerial Departments CABINET OFFICE March 2021

LIST OF MINISTERIAL RESPONSIBILITIES Including Executive Agencies and Non- Ministerial Departments CABINET OFFICE March 2021 LIST OF MINISTERIAL RESPONSIBILITIES INCLUDING EXECUTIVE AGENCIES AND NON-MINISTERIAL DEPARTMENTS CONTENTS Page Part I List of Cabinet Ministers 2-3 Part II Alphabetical List of Ministers 4-7 Part III Ministerial Departments and Responsibilities 8-70 Part IV Executive Agencies 71-82 Part V Non-Ministerial Departments 83-90 Part VI Government Whips in the House of Commons and House of Lords 91 Part VII Government Spokespersons in the House of Lords 92-93 Part VIII Index 94-96 Information contained in this document can also be found on Ministers’ pages on GOV.UK and: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/government-ministers-and-responsibilities 1 I - LIST OF CABINET MINISTERS The Rt Hon Boris Johnson MP Prime Minister; First Lord of the Treasury; Minister for the Civil Service and Minister for the Union The Rt Hon Rishi Sunak MP Chancellor of the Exchequer The Rt Hon Dominic Raab MP Secretary of State for Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Affairs; First Secretary of State The Rt Hon Priti Patel MP Secretary of State for the Home Department The Rt Hon Michael Gove MP Minister for the Cabinet Office; Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster The Rt Hon Robert Buckland QC MP Lord Chancellor and Secretary of State for Justice The Rt Hon Ben Wallace MP Secretary of State for Defence The Rt Hon Matt Hancock MP Secretary of State for Health and Social Care The Rt Hon Alok Sharma MP COP26 President Designate The Rt Hon -

Crown Commercial Service Annual Report and Accounts 2014/15

Annual Report and Accounts 2014/15 Crown Commercial Service Annual Report and Accounts 2014/15 Presented to Parliament pursuant to Section 4 (6A) (b) of the Government Trading Funds Act 1973 (as amended by the Government Trading Act 1990). Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed on 20 July 2015. HC207 © Crown copyright 2015 This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/ doc/open-government-licence/version/3 or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected]. Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. This publication is available at www.gov.uk/government/publications Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us at www.gov.uk/ccs Print ISBN 9781474116671 Web ISBN 9781474116688 ID 12031501 07/15 Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fibre content minimum Printed in the UK by the Williams Lea Group on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office Crown Commercial Service Annual Report and Accounts 2014/15 Contents Welcome 05 Chair’s overview 06-07 Chief Executive’s review of the year 08-11 Key statistics 12-13 Accounts for the year ended 31 March 2015 Management commentary Part 1: Strategic report incorporating the sustainability report 16-25 Part 2: Directors’ report 26-31 Remuneration report 32-35 Statement of Crown -

UKSA Annual Report 2018-19

UK Statistics Authority Annual Report and 2018/19 Accounts Annual Report and Accounts 2018/19 ISBN 978-1-5286-1218-0 CCS0419089792 07/19 HC 2115 HC 2115 UK Statistics Authority Annual Report and Accounts 2018/19 Accounts presented to the House of Commons pursuant to section 6(4) of the Government Resources and Accounts Act 2000 Accounts presented to the House of Lords by Command of Her Majesty Annual Report presented to Parliament pursuant to section 27(2) of the Statistics and Registration Service Act 2007 Annual Report presented to the Scottish Parliament pursuant to section 27(2) of the Statistics and Registration Service Act 2007 Annual Report presented to the National Assembly for Wales pursuant to section 27(2) of the Statistics and Registration Service Act 2007 Annual Report presented to the Northern Ireland Assembly pursuant to section 27(2) of the Statistics and Registration Service Act 2007 Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 4 July 2019 HC 2115 UKSA/2019/01 Note UK Statistics Authority is referred to as ‘the Statistics Board’ in the Statistics and Registration Service Act 2007 This is part of a series of departmental publications which, along with the Main Estimates 2018/19 and the document Public Expenditure: Statistical Analyses 2013, present the Government’s outturn for 2018/19 and planned expenditure for 2018/19. © Crown copyright 2019 This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3 Where we have identified any third-party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. -

Contract Management Handbook

The University of Texas System CONTRACT MANAGEMENT HANDBOOK The University of Texas System Administration Page 1 Contract Management Handbook (9-6-2019) TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter 1 Introduction ..................................................................................................... 4 1.1 Purpose .................................................................................................. 4 1.2 Definitions .............................................................................................. 6 1.3 Acronyms ............................................................................................. 11 1.4 Training for Purchasing Personnel and Contract Managers ................ 12 1.5 Ethics Standards and Policies .............................................................. 13 1.6 Conflict of Interest ................................................................................ 15 1.7 New Ethics Requirements from Senate Bill 20 (2015) ......................... 17 1.8 Disclosure of Interested Parties ........................................................... 19 Chapter 2 Planning ......................................................................................................... 21 2.1 Contract Management Team ............................................................... 22 2.2 Communications Plan ......... 24 2.3 Determining Competitive Procurement Method ................................... 25 2.4 Planning for Contract Content .............................................................. 34 2.5 Information