Feasibility Study Priory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

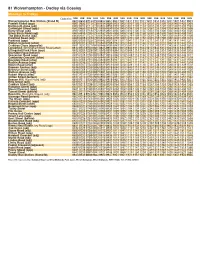

81 Wolverhampton

81 Wolverhampton - Dudley via Coseley Mondays to Fridays Operator: NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB Wolverhampton Bus Station (Stand B) 0600 0650 0715 0748 0832 0857 0931 1001 1031 1101 1131 1201 1231 1301 1331 1401 1431 1501 Powlett Street (opp) 0601 0652 0717 0750 0834 0859 0933 1003 1033 1103 1133 1203 1233 1303 1333 1403 1433 1503 Dartmouth Arms (adj) 0602 0652 0717 0750 0834 0859 0933 1003 1033 1103 1133 1203 1233 1303 1333 1403 1433 1503 Cartwright Street (opp) 0603 0653 0718 0751 0835 0900 0934 1004 1034 1104 1134 1204 1234 1304 1334 1404 1434 1505 Derry Street (adj) 0604 0654 0719 0752 0836 0901 0935 1005 1035 1105 1135 1205 1235 1305 1335 1405 1435 1505 Silver Birch Road (adj) 0605 0655 0720 0753 0837 0902 0936 1006 1036 1106 1136 1206 1236 1306 1336 1406 1436 1507 The Black Horse (adj) 0606 0657 0722 0755 0839 0904 0938 1008 1038 1108 1138 1208 1238 1308 1338 1408 1438 1508 Parkfield Road (adj) 0608 0658 0723 0756 0840 0905 0939 1009 1039 1109 1139 1209 1239 1309 1339 1409 1439 1510 Parkfield (opp) 0609 0700 0725 0758 0842 0907 0941 1011 1041 1111 1141 1211 1241 1311 1341 1411 1441 1511 Walton Crescent (after) 0610 0701 0726 0759 0843 0908 0942 1012 1042 1112 1142 1212 1242 1312 1342 1412 1442 1513 Crabtree Close (opposite) 0611 0702 0727 0800 0844 0909 0943 1013 1043 1113 1143 1213 1243 1313 1343 1413 1443 1514 Lanesfield, Birmingham New Road (after) 0612 0703 0728 0801 0845 0910 0944 1014 1044 1114 1144 1214 1244 1314 1344 1414 1444 1515 Ettingshall Park Farm (opp) 0612 0703 0728 0801 -

82 Wolverhampton

82 Wolverhampton - Dudley via Bilston, Coseley Mondays to Fridays Operator: NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB Wolverhampton Bus Station (Stand P) 0620 0655 0715 0735 0755 0815 0835 0900 0920 0940 1000 1020 1040 1100 1120 Moseley, Deansfield School (adj) 0629 0704 0724 0746 0806 0826 0846 0910 0930 0950 1010 1030 1050 1110 1130 Bilston, Bilston Bus Station (Stand G) ARR 0640 0717 0737 0801 0821 0841 0901 0924 0944 1004 1024 1044 1104 1124 1144 Bilston Bus Station (Stand G) DEP0600 0620 0643 0700 0720 0740 0802 0824 0844 0904 0927 0947 1007 1027 1047 1107 1127 1147 Wallbrook, Norton Crescent (adj) 0607 0627 0650 0707 0727 0747 0809 0832 0852 0912 0935 0955 1015 1035 1055 1115 1135 1155 Roseville, Vicarage Road (before) 0613 0633 0656 0713 0733 0753 0815 0838 0858 0918 0941 1001 1021 1041 1101 1121 1141 1201 Wrens Nest Estate, Parkes Hall Road (after) 0617 0637 0700 0717 0737 0757 0820 0843 0903 0923 0946 1006 1026 1046 1106 1126 1146 1206 Dudley Bus Station (Stand N) 0627 0647 0710 0728 0748 0808 0832 0855 0915 0934 0957 1017 1037 1057 1117 1137 1157 1217 Mondays to Fridays Operator: NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB Wolverhampton Bus Station (Stand P) 1140 1200 1220 1240 1300 1320 1340 1400 1420 1440 1500 1523 1548 1613 1633 1653 1713 1733 Moseley, Deansfield School (adj) 1150 1210 1230 1250 1310 1330 1350 1410 1430 1450 1510 1533 1558 1623 1643 1703 1723 1743 Bilston, Bilston Bus Station (Stand G) ARR1204 1224 1244 1304 1324 1344 1404 1424 1444 1504 1524 1547 1612 -

17Th March, 2014 at 6.30 P.M

ACTION NOTES OF THE CASTLE AND PRIORY, ST. JAMES’S AND ST. THOMAS’S COMMUNITY FORUM Monday, 17th March, 2014 at 6.30 p.m. at Wrens Nest Community Centre, Summer Road, Dudley PRESENT:- Councillor K. Finch (Chair) Councillor A. Ahmed (Vice Chair) Councillors K. Ahmed, Ali, M. Aston, A. Finch and Roberts Lead Officer - S Griffiths, Directorate of Corporate Resources 20 members of the public 29 WELCOME AND INTRODUCTIONS The Chair welcomed everyone to the meeting. Following general announcements, the ward Councillors introduced themselves. 30 APOLOGY FOR ABSENCE An apology for absence from the meeting was submitted on behalf of Councillor Waltho. 31 LISTENING TO YOU: QUESTIONS AND COMMENTS FROM LOCAL RESIDENTS Local residents raised questions and made comments, as set out below. Where necessary, these issues would be referred to the relevant Directorate or appropriate body for a response:- Nature of Question/Comments (1) Various issues were raised concerning parking at Russells Hall Hospital and on the Russells Hall Estate. A request was made for the Council to participate in a partnership approach with the NHS and the private sector to provide a multi-storey car park on land opposite the Hospital, with the adoption of reasonable car parking charges. Reference was also made to speeding, congestion, parking on pavements, vehicles blocking driveways and heavy goods traffic using the Estate as a short cut. The Cabinet Member for Transport noted the ongoing issues and responded to specific points. Concerns about parking at Russells Hall would remain under consideration and be raised with the Hospital Trust as necessary. CPSJSTCF/19 (2) The Cabinet Member for Transport indicated that, following public consultation, the scheme for residents’ parking permits would not be taken forward. -

Committee Minutes

COMMITTEE AND SUB- COMMITTEE MINUTES JUNE 2014 TO SEPTEMBER 2014 AND DELEGATED DECISION SUMMARIES (see delegated decision summaries page for details of how to access decision sheets) LIST OF MEETINGS Committee/Fora Dates Pages From To COMMUNITY FORA Kingswinford North and 01/07/2014 KCF/1 KCF/3 Wallheath,Kingswinford South and Wordsley Kingswinford North and 09/09/2014 KCF/4 KCF/8 Wallheath,Kingswinford South and Wordsley Brierley Hill and Brockmoor and 01/07/2014 BHCF/1 BHCF/4 Pensnett Brierley Hill and Brockmoor and 10/09/2014 BHCF/5 BHCF/6 Pensnett Belle Vale and Hayley Green and 02/07/2014 BVCF/1 BVCF/4 Cradley South Belle Vale and Hayley Green and 09/09/2014 BVCF/5 BVCF/7 Cradley South Amblecote,Cradley and Wollescote 02/07/2014 ACF/1 ACF/3 and Lye and Stourbridge North Amblecote,Cradley and Wollescote 10/09/2014 ACF/4 ACF/7 and Lye and Stourbridge North Netherton,Woodside and St Andrews 01/09/2014 NQCF/4 NQCF/7 and Quarry Bank and Dudley Wood Gornal and Upper Gornal and 01/09/2014 GCF/4 GCF/6 Woodsetton Coseley East and Sedgley 02/09/2014 CSCF/4 CSCF/6 Halesowen North and Halesowen 02/09/2014 HCF/4 HCF/6 South Norton,Pedmore and Stourbridge East 03/09/2014 NPCF/4 NPCF/6 and Wollaston and Stourbridge Town Castle and Priory,St James’s and St 03/09/2014 CPCF/7 CPCF/10 Thomas SCRUTINY COMMITTEES Overview and Scrutiny Management 08/09/2014 OSMB/6 OSMB/12 Board Adult,Community and Housing 07/07/2014 ACHS/1 ACHS/6 Services Adult,Community and Housing 15/09/2014 ACHS/7 ACHS/13 Services Urban Environment 09/07/2014 UE/1 UE/5 Health 16/07/2014 -

Dudley Council Childcare Sufficiency Assessment

Dudley Council Childcare Sufficiency Assessment 2011 – 2014 Childcare Strategy Team March 2011 1 Table of contents 1. Executive summary 2. Purpose 3. Background 3.1 Requirement of the Childcare Act 2006 3.2 Format of the assessment 3.3 Community areas 3.4 Guidance 3.5 Children and Young People’s Plan 2010 -2011 3.6 Links with other local authorities 4. Definitions 4.1 What is childcare? 4.2 What is sufficiency? 4.3 The 9 benchmarks of sufficiency 5. Types of childcare 5.1 Early years register 5.2 Childcare register compulsory and voluntary 5.3 Maintained sector 5.4 Extended services 6. Borough data and information 6.1 Numbers of children in Dudley by township and age 6.2 Ethnicity 6.3 Areas of deprivation 6.4 Children in “Poverty” 6.5 Single parent households 6.6 Unemployment (worklessness) 6.7 Earnings 7. Demand for childcare 7.1 Childcare audit/questionnaires 7.2 Type of childcare available and usage 7.3 Location of childcare 7.4 Childcare provider questionnaire analysis 7.5 Unregistered childcare 7.6 Paying for childcare 7.7 Children with disabilities 7.8 Barriers to childcare identified by Jobcentre Plus 7.9 Childcare quality 7.10 Childcare & Early Years workforce 2 8. Mapping and market managing the supply of childcare 8.1 Childcare by township and type – settings and places 8.2 Childcare costs 8.3 Help with childcare costs 8.4 Childcare information and Working Tax Credits 8.5 The free entitlement for 3 & 4yr olds (Extra time for three’s & fours) 8.6 2yr old pilot (Time for Two’s) 8.7 Children’s centres 8.8. -

The London Gazette, 12 January, 1932

THE LONDON GAZETTE, 12 JANUARY, 1932. 291 Wells Avenue,}Upper Perm; The Quarry Bank Urban District Council: Reddall Hill Road, Old Hill; Clerk's Office, .Stevens Park, Quarry Bank, Thorns Road, Quarry Bank; Staffordshire. Bank Street, Brierley Hill; The Rowley Regis Urban District Council: 31, High Street, Stourbridge; Clerk's Office, The Council Offices, Old Hill, and at the following addresses:— Staffordshire. " Roseleigh " The Paddock, Ooseley. The Sedgley Urban District Council: The Council House, Sedgley. Clerk's Office, The Council House, Sedgley, 53, High Road, Lane Head, Short Heath. near Dudley, Worcestershire. 5, High Street, Wednesfield. 62, King William Street, Amblecote. The Short Heath Urban District Council: "Halibon" Bentley, near Willenhall. Clerk's Office, 33, Market Place, Willenhall, 2B, Foundry Road, Wall He'ath, Kings- Staffordshire. winford. The Wednesfield Urban District Council: Bank Ohambers, High Street, Lye, iStour- Clerk's Office, 44, Queen Street, Woilver- bridge. hampton. 2, Lilac Road, Priory Estate, Dudley. The Willenhall Urban District Council: The Post Office, Claverley. Clerk's Office, The Town Hall, Willenhall, And notice is hereby further given that in Staffordshire. accordance with the Electricity Commissioners The Tipton. Urban District Council: Special Orders &c. Rules 1930, a copy of the Clerk's Office, The Public Offices, Owen draft Order, and a map shewing the proposed Street, Tipton, Staffordshire. area of supply, and the .streets in which it is The Bridgnorth Rural District Council: proposed that electric lines shall be laid down Clerk's Office, High Street, Bridgnorth, within a specified time 'have been deposited Salop. for public inspection with the Clerk of the The Kingswinford Rural District Council: Peace for the County of Stafford at his office Clerk's Office, Wordsley, Stourbridge, at County Buildings, Stafford, with the Clerk Worcestershire. -

Pharmaceutical Needs Assessment (PNA) Office of Public Health Dudley, 2018-2021

Pharmaceutical Needs Assessment (PNA) Office of Public Health Dudley, 2018-2021 Produced in accordance with the National Health Service (Pharmaceutical Services and Local Pharmaceutical Services) Regulation 2013 60 day Consultation period: 12th December 2017 to 13th February 2018 Approved by Dudley Health and Wellbeing Board: Published: 5th April 2018 Supplementary statements will be issued in response to changes to pharmaceutical services since the publication of this PNA. Full revision – April 2021 Authors Jag Sangha, Pharmaceutical Adviser – Community Pharmacy and Public Health, Dudley CCG Laura Brennan, Senior Intelligence Analyst, Dudley MBC Acknowledgements Core Team (Steering Group) Jag Sangha, Pharmaceutical Adviser – Community Pharmacy and Public Health, Dudley CCG Laura Brennan, Senior Intelligence Analyst, Dudley MBC Dr David Pitches, Head of Service, Healthcare Public Health and Consultant in Public Health Medicine, Dudley MBC Dr Duncan Jenkins, Specialist in Pharmaceutical Public Health, Dudley CCG Pete Szczepanski, Chief Officer, Dudley Local Pharmaceutical Committee Michelle Dyoss, Public Health Practitioner, Dudley Local Pharmaceutical Committee Greg Barbosa, Senior Public Health Intelligence Specialist, Dudley MBC Brian Wallis, Contract Manager, NHS England West Midlands Area Team (until August 2017) Michelle Deenah, Contract Manager NHS England West Midlands Area Team (from September 2017) Rob Dalziel, Healthwatch Dudley (Public Engagement) Dr Timothy Horsburgh, Dudley Local Medical Committee Joanne Taylor, Commissioning Manager, Dudley CCG Dino Motti, Public Health Registrar, Dudley MBC (Vulnerable Childrens Medicines Needs Assessment, page 126) Susan Wheeler, Business Support Officer, Dudley MBC (Administration Assistance) Groups involved or consulted during development: Dudley MBC, Dudley CCG, Dudley community pharmacies, Substance Misuse Service (Change, Grow and Live), Let’s Get Healthy Team, Solutions 4 Health Ltd, NHS Health Checks, Sexual Health Service and the public (through HealthWatch Dudley). -

Healthwatch Dudley the Priory Community Pharmacy

Healthwatch Dudley The Priory Community Pharmacy People’s views on what it does for them July 2015 1 Contents Page Tables and Figures …………………………………………………………………………………… 3 Acknowledgements …………………………………………………………………………………. 4 Executive Summary …………………………………………………………………………………. 5 Introduction …………………………………………………………………………………………….. 7 Background ………………………………………………………………………………………………. 7 Castle and Priory Ward ……………………………………………………………………………… 8 Pharmacies ……………………………………………………………………………………………….. 9 The Young Pharmacists Group ………………………………………………………………….. 10 The Priory Community Pharmacy ……………………………………………………………… 10 The research team ………………………………………………………………………………….. 13 How we carried out the research…………………………………………………………… 13 Scoping and planning work…………………………………………………………………………. 14 Questionnaire survey …………………………………………………………………………………. 14 Focus group work………….……………………………………………………………………………. 14 Semi-structured interviews………………………………………………………………………… 15 What people were saying …………………………………………………………………………. 15 Questionnaire survey responses …………………………………………………………………. 15 The Priory Community Pharmacy Stakeholder Group…………………………………. 24 Community groups and residents ……………………………………………………………….. 26 What does it all mean? ………………………………………………………………………………. 28 Findings and implications .…………………………………………………………………………. 29 Appendices ………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 31 2 Tables, Figures and Diagrams Page Tables 1. Pharmacy enhanced services ……………………………………………………… 9 2. Pharmacy First Minor Ailments Scheme ……………………………………. 10 3. Additional pharmacy services ……………………………………………………. -

Dudley Schools Forum

Dudley Schools Forum Membership – as of 1st October 2007 John Freeman, Director of Children’s Services Councillor Liz Walker, Cabinet Member for Children’s Services Councillor Harry Nottingham, Chair of Select Committee on Children’s Services Schools Members One secondary school headteacher for each of the five townships, nominated by the Secondary Headteachers Forum Brierley Hill D Francis, The Crestwood School Bromley Lane, Kingswinford, Dudley, DY9 0JH. (Membership expires 30th September, 2009) Central Dudley Graham Lloyd, Holly Hall Maths and Computing College, Scotts Green Close, Russells Hall Estate, Dudley, DY1 2DU. (Membership expires 30th September, 2010) Halesowen K Sorrell, Windsor High School, Richmond Street, Halesowen, B63 4BB. (Membership expires 30th September, 2008) North Dudley Mandy Elwiss, The Coseley School, Henne Drive, Coseley, Bilston WV14 9JH (Membership expires 30th September, 2009) Stourbridge David Mountney, Thorns Community College, off Stockwell Avenue, Quarry Bank, Brierley Hill DY5 2NU. (Membership expires 30th September, 2009) One secondary school governor for each of the five townships, nominated by the Dudley Association of Governing Bodies Executive Brierley Hill Mr C Wassall, 55 Ridge Road, Kingswinford, West Midlands DY6 9RE. (Membership expires 30th September, 2009) Central Dudley Mrs T Blunt, 98 Hockley Lane, Netherton, Dudley, West Midlands DY2 0JN. (Membership expires 30th September, 2010) Halesowen Mr S Bell, 34 Wall Well, Halesowen, B63 4SJ. (Membership expires 30th September, 2008) North Dudley Mr L Ridney, 38 Gough Road, Coseley, Bilston, West Midlands WV14 8XS. (Membership expires 30th September, 2009) Stourbridge Mr J Conway, 31 South Avenue, Stourbridge, DY8 3XY. (Membership expires 30th September, 2008) One primary school headteacher for each of the five townships, nominated by the Primary Headteachers Forum Brierley Hill Mrs J O’Neill, Glynne Primary School, Cot Lane, Kingswinford, Dudley DY6 9TH. -

X8 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

X8 bus time schedule & line map X8 Birmingham - Wolverhampton via Blackheath, View In Website Mode Dudley The X8 bus line (Birmingham - Wolverhampton via Blackheath, Dudley) has 5 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Birmingham: 4:30 AM - 10:15 PM (2) Dudley: 4:52 AM - 11:15 PM (3) Hurst Green: 5:18 PM (4) Quinton: 7:40 AM - 4:40 PM (5) Wolverhampton: 5:20 AM - 11:30 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest X8 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next X8 bus arriving. Direction: Birmingham X8 bus Time Schedule 70 stops Birmingham Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 7:20 AM - 10:15 PM Monday 4:30 AM - 10:15 PM Wolverhampton Bus Station Five Ways, Birmingham/Wolverhampton/Walsall/Dudley Tuesday 4:30 AM - 10:15 PM Old Hall St, Wolverhampton Wednesday 4:30 AM - 10:15 PM Temple St, Wolverhampton Thursday 4:30 AM - 10:15 PM Snow Hill, Birmingham/Wolverhampton/Walsall/Dudley Friday 4:30 AM - 10:15 PM Derry St, Blakenhall Saturday 5:00 AM - 10:15 PM Silver Birch Rd, Blakenhall The Black Horse, Rough Hills X8 bus Info Parkƒeld Rd, Parkƒeld Direction: Birmingham Stops: 70 Parkƒeld Trip Duration: 83 min Line Summary: Wolverhampton Bus Station, Old Hall Walton Crescent, Parkƒeld St, Wolverhampton, Temple St, Wolverhampton, Derry St, Blakenhall, Silver Birch Rd, Blakenhall, The Black Horse, Rough Hills, Parkƒeld Rd, Parkƒeld, Crabtree Close, Parkƒeld Parkƒeld, Walton Crescent, Parkƒeld, Crabtree Close, Parkƒeld, Laburnam Rd, Lanesƒeld, Hill Avenue, Laburnam Rd, Lanesƒeld Lanesƒeld, Rookery Rd, Lanesƒeld, Meadow -

Training New Members May 09

APPENDIX 3 1 May 2009 to 1 May 2009 to 1 May 2009 to SCHOOL MEMBERS DUDLEY SCHOOLS FORUM CONSTITUTION FROM MAY 2009 30 April 2010 30 April 2011 30 April 2012 Primary School Headteachers One primary school headteacher for each of the five townships Brierley Hill Mr S Hudson, Crestwood Park Primary School, Lapwood Avenue, Crestwood Park Estate, Kingswinford DY6 8RP √√ Central Dudley Mr M Millman, Priory Primary School, Cedar Road, Priory Estate, Dudley DY1 4HN √√√ Halesowen Mr M James, Howley Grange Primary School √√√ North Dudley Mrs P Hazlehurst, Christ Church Primary School √ Stourbridge P Harrington, Ham Dingle Primary School, Old Ham Lane, Pedmore, Stourbridge DY9 0UN. √√ Primary School Governors One primary school governor for each of the five townships Brierley Hill Mr R Timmins, Crestwood Park Primary School √ Central Dudley Mrs H M Edwards, Dudley Wood Primary School √√√ Halesowen Denise Micke, Our Lady and St Knelm Primary School √√√ North Dudley Mr J T Jones, Redhall Primary School √√ Stourbridge David Yates, Hob Green Primary School √√ Secondary School Headteachers One secondary school headteacher for each of the five townships Brierley Hill D Francis, The Crestwood School Bromley Lane, Kingswinford, Dudley, DY9 0JH √√ Central Dudley April Garratt, Hillcrest School and Community College, Simms Lane, Dudley, DY2 0PB √ Halesowen K Sorrell, Windsor High School, Richmond Street, Halesowen, B63 4BB. √√√ North Dudley Mrs A Elwiss, The Coseley School, Henne Drive, Coseley, Bilston WV14 9JH √√√ Stourbridge Mr Clive Nutting, Ridgewood -

Crosswords Local History Pictures from the Past and More! We Hope You Enjoy Our Buster!

Crosswords Local history Pictures from the past And more! We hope you enjoy our buster! With love Broadway Halls Care Home The Broadway Dudley DY1 3EA History of Dudley Dudley began as a Saxon village. It was originally called Dudda's leah. The Saxon word leah meant a clearing in a forest. Dudley later became known as the capital of the Black Country. In the 11th century a castle was built at Dudley. At first it was made of wood but in the 12th century it was rebuilt in stone. In 1647 after the civil war between king and parliament Dudley castle was 'slighted' or damaged to prevent it ever being used by the royalists. A fire damaged the remains of Dudley Castle in 1750. In the Middle Ages Dudley also had a priory or small monastery nearby. Dudley was changed from a village to a town in the 13th century when the Lord of the Manor started a market there. In the middle Ages there were very few shops and anyone who wished to buy or sell anything had to go to a market. Dudley soon grew into a flourishing little community. In the middle Ages the area was already known for its coal mines. By the 16th century Dudley was known for nail making. In 1562 a grammar school was founded in Dudley. In 1685 Dudley was granted the right to hold 2 annual fairs. (Fairs were like markets but tended to specialize in one commodity like horses. People would come from all over the West Midlands to buy and sell at Dudley fair).