An Examination and Evaluation of Women's Programming at National Public Radio Affiliate Stations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View a Printable PDF About IPBS Here

INDIANA PUBLIC BROADCASTING STATIONS Indiana Public Broadcasting Stations (IPBS) is a SERVING HOOSIERS non-profi t corporation comprised of nine NPR radio Through leadership and investment, IPBS stations and eight PBS television stations. It was supports innovation to strengthen public media’s founded on the principle that Indiana’s public media programming and services. It seeks to deepen stations are stronger together than they are apart engagement among Hoosiers and address the and our shared objective is to enrich the lives of rapidly changing ways our society uses media today. Hoosiers every day. IPBS’s priorities are to: IPBS reaches 95% of Indiana’s population • Assist students of all ages with remote through their broadcasts and special events. learning and educational attainment • Aid Indiana’s workforce preparation More than TWO MILLION HOOSIERS consume and readiness IPBS news and programming on a weekly basis. • Expand access to public media content and services in underserved regions IPBS member stations off er local and national • Address Hoosiers’ most pressing health, content. They engage viewers and listeners through social, and economic concerns, including programming, special events and public discussions those brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic that are important to Indiana communities. IPBS • Improve quality of life for all enriches lives by educating children, informing and connecting citizens, celebrating our culture and Programming and Service Areas environment, and instilling the joy of learning. • Government & Politics -

Federal Register / Vol. 61, No. 99 / Tuesday, May 21, 1996 / Notices

25528 Federal Register / Vol. 61, No. 99 / Tuesday, May 21, 1996 / Notices DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE Closing Date, published in the Federal also purchase 74 compressed digital Register on February 22, 1996.3 receivers to receive the digital satellite National Telecommunications and Applications Received: In all, 251 service. Information Administration applications were received from 47 states, the District of Columbia, Guam, AL (Alabama) [Docket Number: 960205021±6132±02] the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, File No. 96006 CTB Alabama ETV RIN 0660±ZA01 American Samoa, and the Commission, 2112 11th Avenue South, Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Ste 400, Birmingham, AL 35205±2884. Public Telecommunications Facilities Islands. The total amount of funds Signed By: Ms. Judy Stone, APT Program (PTFP) requested by the applications is $54.9 Executive Director. Funds Requested: $186,878. Total Project Cost: $373,756. AGENCY: National Telecommunications million. Notice is hereby given that the PTFP Replace fourteen Alabama Public and Information Administration, received applications from the following Television microwave equipment Commerce. organizations. The list includes all shelters throughout the state network, ACTION: Notice, funding availability and applications received. Identification of add a shelter and wiring for an applications received. any application only indicates its emergency generator at WCIQ which receipt. It does not indicate that it has experiences AC power outages, and SUMMARY: The National been accepted for review, has been replace the network's on-line editing Telecommunications and Information determined to be eligible for funding, or system at its only production facility in Administration (NTIA) previously that an application will receive an Montgomery, Alabama. announced the solicitation of grant award. -

Return of Private Foundation CT' 10 201Z '

Return of Private Foundation OMB No 1545-0052 Form 990 -PF or Section 4947(a)(1) Nonexempt Charitable Trust Department of the Treasury Treated as a Private Foundation Internal Revenue Service Note. The foundation may be able to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting requirem M11 For calendar year 20 11 or tax year beainnina . 2011. and ending . 20 Name of foundation A Employer Identification number THE PFIZER FOUNDATION, INC. 13-6083839 Number and street (or P 0 box number If mail is not delivered to street address ) Room/suite B Telephone number (see instructions) (212) 733-4250 235 EAST 42ND STREET City or town, state, and ZIP code q C If exemption application is ► pending, check here • • • • • . NEW YORK, NY 10017 G Check all that apply Initial return Initial return of a former public charity D q 1 . Foreign organizations , check here . ► Final return Amended return 2. Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, check here and attach Address chang e Name change computation . 10. H Check type of organization' X Section 501( exempt private foundation E If private foundation status was terminated Section 4947 ( a)( 1 ) nonexem pt charitable trust Other taxable p rivate foundation q 19 under section 507(b )( 1)(A) , check here . ► Fair market value of all assets at end J Accounting method Cash X Accrual F If the foundation is in a60-month termination of year (from Part Il, col (c), line Other ( specify ) ---- -- ------ ---------- under section 507(b)(1)(B),check here , q 205, 8, 166. 16) ► $ 04 (Part 1, column (d) must be on cash basis) Analysis of Revenue and Expenses (The (d) Disbursements total of amounts in columns (b), (c), and (d) (a) Revenue and (b) Net investment (c) Adjusted net for charitable may not necessanly equal the amounts in expenses per income income Y books purposes C^7 column (a) (see instructions) .) (cash basis only) I Contribution s odt s, grants etc. -

Broadcast Actions 5/29/2014

Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 48249 Broadcast Actions 5/29/2014 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR RENEWAL GRANTED NY BR-20140131ABV WENY 71510 SOUND COMMUNICATIONS, LLC Renewal of License. E 1230 KHZ NY ,ELMIRA Actions of: 04/29/2014 FM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR MODIFICATION OF LICENSE GRANTED OH BMLH-20140415ABD WPOS-FM THE MAUMEE VALLEY License to modify. 65946 BROADCASTING ASSOCIATION E 102.3 MHZ OH , HOLLAND Actions of: 05/23/2014 AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR RENEWAL DISMISSED NY BR-20071114ABF WRIV 14647 CRYSTAL COAST Renewal of License. COMMUNICATIONS, INC. Dismissed as moot, see letter dated 5/5/2008. E 1390 KHZ NY , RIVERHEAD Page 1 of 199 Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 48249 Broadcast Actions 5/29/2014 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N Actions of: 05/23/2014 AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR ASSIGNMENT OF LICENSE GRANTED NY BAL-20140212AEC WGGO 9409 PEMBROOK PINES, INC. Voluntary Assignment of License From: PEMBROOK PINES, INC. E 1590 KHZ NY , SALAMANCA To: SOUND COMMUNICATIONS, LLC Form 314 NY BAL-20140212AEE WOEN 19708 PEMBROOK PINES, INC. -

Public Notice >> Licensing and Management System Admin >>

REPORT NO. PN-2-210125-01 | PUBLISH DATE: 01/25/2021 Federal Communications Commission 45 L Street NE PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media info. (202) 418-0500 ACTIONS File Number Purpose Service Call Sign Facility ID Station Type Channel/Freq. City, State Applicant or Licensee Status Date Status 0000122670 Renewal of FM KLWL 176981 Main 88.1 CHILLICOTHE, MO CSN INTERNATIONAL 01/21/2021 Granted License From: To: 0000123755 Renewal of FM KCOU 28513 Main 88.1 COLUMBIA, MO The Curators of the 01/21/2021 Granted License University of Missouri From: To: 0000123699 Renewal of FL KSOZ-LP 192818 96.5 SALEM, MO Salem Christian 01/21/2021 Granted License Catholic Radio From: To: 0000123441 Renewal of FM KLOU 9626 Main 103.3 ST. LOUIS, MO CITICASTERS 01/21/2021 Granted License LICENSES, INC. From: To: 0000121465 Renewal of FX K244FQ 201060 96.7 ELKADER, IA DESIGN HOMES, INC. 01/21/2021 Granted License From: To: 0000122687 Renewal of FM KNLP 83446 Main 89.7 POTOSI, MO NEW LIFE 01/21/2021 Granted License EVANGELISTIC CENTER, INC From: To: Page 1 of 146 REPORT NO. PN-2-210125-01 | PUBLISH DATE: 01/25/2021 Federal Communications Commission 45 L Street NE PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media info. (202) 418-0500 ACTIONS File Number Purpose Service Call Sign Facility ID Station Type Channel/Freq. City, State Applicant or Licensee Status Date Status 0000122266 Renewal of FX K217GC 92311 Main 91.3 NEVADA, MO CSN INTERNATIONAL 01/21/2021 Granted License From: To: 0000122046 Renewal of FM KRXL 34973 Main 94.5 KIRKSVILLE, MO KIRX, INC. -

Focus, 2001, Winter Andrews University

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Focus Office of Alumni Services Winter 2001 Focus, 2001, Winter Andrews University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/focus Recommended Citation Andrews University, "Focus, 2001, Winter" (2001). Focus. Book 42. http://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/focus/42 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Office of Alumni Services at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Focus by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WINTER 2001 • THE ANDREWS UNIVERSITY MAGAZINE • VOL. 37 NO. 1 FOCUS Crafting an Image New developments in the photography program MAKING FRIENDS, KEEPING STUDENTS • REMEMBERING TO KILL A MOCKINGBIRD • CLASSNOTES . IN. FOCUS. Building relationships ndrews is a place where professors, faculty and staff aim to tography professors featured in our middle color section. He is provide a pleasant experience for students, both old and drawn to still-life photography and enjoys spending his time Anew. From the registration process to alumni gatherings arranging and rearranging objects to create fascinating visual expe- years after students have left Andrews, the goal is for Andrews to riences. maintain positive relationships with people and point people to Our Bookshelf section this time is crammed full of interesting books Christ through those relationships. written by Andrews alumni and professors. Read doctoral student In this issue, one of our regular writers, Chris Carey, explores the Elias Brasil DeSouza’s critique of professor Jiri Moskala’s doctoral advising world at Andrews and how it affects the relationship dissertation, The Laws of Clean and Unclean Animals in Leviticus 11, Andrews has with students. -

Updated 4/24/2020

Promoter Technical Package Updated 4/24/2020 Morris Performing Arts Center 211 N. Michigan Street South Bend, IN 46601 (574) 235-9198 www.MorrisCenter.org Table of Contents Morris PAC Staff and General Information……………………………………………………. 1 Booking Policies………………………………………………………………………………….. 2 Licensing Application…………………………………………………………………………….. 5 Standard House Expenses……………………………………………………………………… 9 Seating Breakdown by Area……………………………………………………………………..11 Marketing and Advertising………………………………………………………………………..12 Box Office Information…………………………………………………………………………….17 Map of Downtown South Bend……………………………………………………………………18 General Technical Information……………………………………………………………………19 Stage Specifications………………………………………………………………………………. 20 Line Schedule……………………………………………………………………………………… 22 Theater Floor Plans……………………………………………………………………………….. 24 Morris Performing Arts Center 211 N. Michigan Street South Bend, IN 46601 (574) 235-9198 www.MorrisCenter.org Morris Performing Arts Center Promoter/Technical Package Page 1 of 25 Morris PAC Staff and General Information Executive Director of Venues Jeff Jarnecke (574) 235-5796 Director of Booking & Events Jane Moore (574) 235-5901 Operations Manager Mary Ellen Smith (574) 235-9160 Director of Financial Services Marika Anderson (574) 245-6134 Director of Box Office Services & Venue Mgr Michelle DeBeck (574) 245-6135 Box Office Ticketing Line (574) 235-9190 Director of Facility Operations Jim Monroe (574) 245-6074 Production Manager Kyle Miller (574) 245-6136 Facilities Operations FAX (574) 235-9729 Administrative -

Listening Patterns – 2 About the Study Creating the Format Groups

SSRRGG PPuubblliicc RRaaddiioo PPrrooffiillee TThhee PPuubblliicc RRaaddiioo FFoorrmmaatt SSttuuddyy LLiisstteenniinngg PPaatttteerrnnss AA SSiixx--YYeeaarr AAnnaallyyssiiss ooff PPeerrffoorrmmaannccee aanndd CChhaannggee BByy SSttaattiioonn FFoorrmmaatt By Thomas J. Thomas and Theresa R. Clifford December 2005 STATION RESOURCE GROUP 6935 Laurel Avenue Takoma Park, MD 20912 301.270.2617 www.srg.org TThhee PPuubblliicc RRaaddiioo FFoorrmmaatt SSttuuddyy:: LLiisstteenniinngg PPaatttteerrnnss Each week the 393 public radio organizations supported by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting reach some 27 million listeners. Most analyses of public radio listening examine the performance of individual stations within this large mix, the contributions of specific national programs, or aggregate numbers for the system as a whole. This report takes a different approach. Through an extensive, multi-year study of 228 stations that generate about 80% of public radio’s audience, we review patterns of listening to groups of stations categorized by the formats that they present. We find that stations that pursue different format strategies – news, classical, jazz, AAA, and the principal combinations of these – have experienced significantly different patterns of audience growth in recent years and important differences in key audience behaviors such as loyalty and time spent listening. This quantitative study complements qualitative research that the Station Resource Group, in partnership with Public Radio Program Directors, and others have pursued on the values and benefits listeners perceive in different formats and format combinations. Key findings of The Public Radio Format Study include: • In a time of relentless news cycles and a near abandonment of news by many commercial stations, public radio’s news and information stations have seen a 55% increase in their average audience from Spring 1999 to Fall 2004. -

2010 Npr Annual Report About | 02

2010 NPR ANNUAL REPORT ABOUT | 02 NPR NEWS | 03 NPR PROGRAMS | 06 TABLE OF CONTENTS NPR MUSIC | 08 NPR DIGITAL MEDIA | 10 NPR AUDIENCE | 12 NPR FINANCIALS | 14 NPR CORPORATE TEAM | 16 NPR BOARD OF DIRECTORS | 17 NPR TRUSTEES | 18 NPR AWARDS | 19 NPR MEMBER STATIONS | 20 NPR CORPORATE SPONSORS | 25 ENDNOTES | 28 In a year of audience highs, new programming partnerships with NPR Member Stations, and extraordinary journalism, NPR held firm to the journalistic standards and excellence that have been hallmarks of the organization since our founding. It was a year of re-doubled focus on our primary goal: to be an essential news source and public service to the millions of individuals who make public radio part of their daily lives. We’ve learned from our challenges and remained firm in our commitment to fact-based journalism and cultural offerings that enrich our nation. We thank all those who make NPR possible. 2010 NPR ANNUAL REPORT | 02 NPR NEWS While covering the latest developments in each day’s news both at home and abroad, NPR News remained dedicated to delving deeply into the most crucial stories of the year. © NPR 2010 by John Poole The Grand Trunk Road is one of South Asia’s oldest and longest major roads. For centuries, it has linked the eastern and western regions of the Indian subcontinent, running from Bengal, across north India, into Peshawar, Pakistan. Horses, donkeys, and pedestrians compete with huge trucks, cars, motorcycles, rickshaws, and bicycles along the highway, a commercial route that is dotted with areas of activity right off the road: truck stops, farmer’s stands, bus stops, and all kinds of commercial activity. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra

■ ••••••• 0•L • Boston Symphony Orchestra Seiji Ozawa, Music Director Colin Davis, Principal Guest Conductor Joseph Silverstein, Assistant Conductor Thursday, January 29, 1976 at 8:30 p.m. Friday, January 30, 1976 at 2:00 p.m. Saturday, January 31, 1976 at 8:30 p.m. Symphony Hall, Boston Ninety-fifth Season Baldwin Piano Deutsche Grammophon & Philips Records Program Program Notes Seiji Ozawa conducting Gioacchino Antonio Rossini (1792-1868) Overture to the Opera 'Semiramide' Rossini: Overture to the Opera 'Semiramide' This opera in two acts on a libretto of Gaetano Rossi Griffes: 'The Pleasure Dome of Kubla Khan' (based on Voltaire's tragedy of the same name) was first (After the Poem of S. T. Coleridge) performed at the Fenice Theatre, Venice in February 1823. It was mounted at La Scala, Milan in 1824. The first per- formance in Boston was at the Federal Street Theatre, Intermission March 3, 1851. It was last performed by the Boston Sym- phony in Boston in 1953 by the late Guido Cantelli, and Bruckner: Symphony No. 4 in E flat 'Romantic' most recently at the Berkshire Festival in 1975 conducted by Arthur Fiedler. Ruhig Bewegt (Tranquillo, con moto) Rossini, piqued by unfavorable comments by no less an Andante authority than Beethoven himself regarding opera seria sat Scherzo: Bewegt (Con moto) Trio (Gernachlich) down and wrote a long tragedy in music in the grand style Finale: Massig Bewegt (Moderato, con moto) ('melodramma (sic) tragico') in seven days less than the forty his contract allowed. 'Semiramide' was premiered at La The Friday program will end about 3:25 p.m. -

Bandera Bastrop Bay City Baytown Beaumont Beeville

KKCN Country KQXY-F CHR 103.1 100000W 456ft Baytown 94.1 100000W 600ft +Encore Broadcasting, LLC APP 100000, 361 KWWJ Black Gospel / Religious Teaching Sister to: KELI, KGKL, KGKL-F, KNRX +Cumulus Media, Inc. 1360 5000/ 1000 DA-2 325-655-7161 fax:325-658-7377 Sister to: KAYD-F, KBED, KFNC, KIKR, KTCX +Darrell E. Martin PO Box 1878, San Angelo 76902 409-833-9421 fax: 409-833-9296 Sister to: KYOK 1301 S Abe St, San Angelo 76903 755 S 11th St Ste 102, 77701 281-837-8777 fax: 281-424-7588 GM/SM John Kerr PD Tracy Scott GM Rick Prusator SM Mike Simpson PO Box 419, 77522, 4638 Decker Dr, 77520 CE Tommy Jenkins PD Brandln Shaw CE Greg Davis GM/SM/PD Darrell Martin CE Dave Blondi www.klckin-country.com www.kqxy.com www.kwwj.org San Angelo Market Beaumont Market Houston/Galveston Market KYKR Country Bandera Beaumont 95.1 100000W 1070ft +Clear Channel Communications KEEP Americana/Adult Alternative [Repeats: KFAN-F 107.9] KLVI Talk Sister to: KCOL-F, KIOC, KKMY, KLVI 103.1 3500w 430ft 560 5000/5000 DA-N 409-896-5555 fax: 409-896-5500 Fritz Broadcasting Co., Inc. +Clear Channel Communications PO Box 5488, 77726, 2885 Interstate 10 E, 77702 Sister to: KFAN-F, KNAF Sister to: KCOL-F, KIOC, KKMY, KYKR GM Vesta Brandt SM Elizabeth Blackstock 830-997-2197 fax: 830-997-2198 409-896-5555 fax: 409-896-5500 PD Mickey Ashworth CE T.J. Bordelon PO Box 311, Fredericksburg 78624 PO Box 5488, 77726, 2885 Interstate 10 E, 77702 www.kykr.com 210 Woodcrest St, Fredericksburg 78624 GM Vesta Brandt SM Elizabeth Blackstock Beaumont Market GM/CE Jayson Fritz SM Jan Fritz PDA! Caldwell CET.J, Bordelon PD Rick Star www.klvl.com KFNC News-Talk www.texasrebelradio.com Beaumont Market 97.5 100000W 1955ft +Cumulus Media, Inc. -

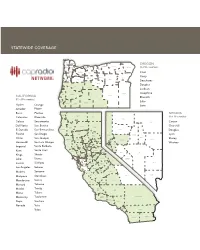

Statewide Coverage

STATEWIDE COVERAGE CLATSOP COLUMBIA OREGON MORROW UMATILLA TILLAMOOK HOOD WALLOWA WASHINGTON MULTNOMAH RIVER (9 of 36 counties) GILLIAM SHERMAN UNION YAMHILL CLACKAMAS WASCO Coos POLK MARION WHEELER Curry JEFFERSON BAKER LINCOLN LINN BENTON GRANT Deschutes CROOK Douglas LANE DESCHUTES Jackson MALHEUR Josephine COOS DOUGLAS HARNEY CALIFORNIA LAKE Klamath (51 of 58 counties) CURRY Lake KLAMATH JOSEPHINE JACKSON Alpine Orange Lane Amador Placer Butte Plumas NEVADA DEL NORTE SISKIYOU Calaveras Riverside MODOC (6 of 16 counties) HUMBOLDT Colusa Sacramento ELKO Carson Del Norte San Benito SHASTA LASSEN Churchill TRINITY El Dorado San Bernardino HUMBOLDT PERSHING Douglas TEHAMA Fresno San Diego WASHOE LANDER Lyon PLUMAS EUREKA Glenn San Joaquin MENDOCINO WHITE PINE Storey GLENN BUTTE SIERRA CHURCHILL STOREY Humboldt San Luis Obispo Washoe NEVADA ORMSBY LYON COLUSA SUTTER YUBA PLACER Imperial Santa Barbara LAKE DOUGLAS Santa Cruz YOLO EL DORADO Kern SONOMA NAPA ALPINE MINERAL NYE SACRAMENTO Kings Shasta AMADOR SOLANO CALAVERAS MARIN TUOLUMNE SAN ESMERALDA Lake Sierra CONTRA JOAQUIN COSTA MONO LINCOLN Lassen Siskiyou ALAMEDA STANISLAUS MARIPOSA SAN MATEO SANTA CLARA Los Angeles Solano MERCED SANTA CRUZ MADERA Madera Sonoma FRESNO SAN CLARK Mariposa Stanislaus BENITO INYO Mendocino Sutter TULARE MONTEREY KINGS Merced Tehama Trinity SAN Modoc LUIS KERN OBISPO Mono Tulare SANTA SAN BERNARDINO Monterey Tuolumne BARBARA VENTURA Napa Ventura LOS ANGELES Nevada Yolo ORANGE Yuba RIVERSIDE IMPERIAL SAN DIEGO CAPRADIO NETWORK: AFFILIATE STATIONS JEFFERSON PUBLIC STATION CITY FREQUENCY STATION CITY FREQUENCY FREQUENCY RADIO - TRANSLATORS KXJZ-FM Sacramento 90.9 KPBS-FM San Diego 89.5 Big Bend, CA 91.3 KXPR-FM Sacramento 88.9 KQVO Calexico 97.7 Brookings, OR 101.7 KXSR-FM Groveland 91.7 KPCC-FM Pasadena 89.3 Burney, CA 90.9 Stockton KUOP-FM 91.3 KUOR-FM Inland Empire 89.1 Callahan/Ft.