Fending for Ourselves: the Civilian Impact of Mali's Three-Year Conflict

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Conflict's Complexity in Northern Mali Calls for Tailored Solutions

Policy Note 1, 2015 By Ole Martin Gaasholt Who needs to reconcile with whom? The Conflict’s Complexity in Northern Mali Calls for Tailored Solutions PHOTO: MARC DEVILLE/GETTY IMAGES While negotiations are taking place in Algiers, some observers insist on the need for reconciliation between Northern Mali and the rest of the country and particularly between Tuareg and other Malians. But the Tuareg are a minority in Northern Mali and most of them did not support the rebels. So who needs to be reconciled with whom? And what economic solutions will counteract conflict? This Policy Note argues that not only exclusion underlies the conflict, but also a lack of economic opportunities. The important Tuareg component in most rebellions in Mali does not mean that all Tuareg participate or even support the rebellions. ll the rebellions in Northern Mali the peoples of Northern Mali, which they The Songhay opposed Tuareg and Arab have been initiated by Tuareg, typi- called Azawad, and not just of the Tuareg. rebels in the 1990s, whereas many of them cally from the Kidal region, whe- There has thus been a sequence of joined Islamists controlling Northern Mali in reA the first geographically circumscribed rebellions in Mali in which the Tuareg 2012. Very few Songhay, or even Arabs, joined rebellion broke out a few years after inde- component has been important. In the Mouvement National pour la Libération pendence in 1960. Tuareg from elsewhere addition, there have been complex de l’Azawad (MNLA), despite the claim that in Northern Mali have participated in later connections between the various conflicts, Azawad was a multiethnic territory. -

From Operation Serval to Barkhane

same year, Hollande sent French troops to From Operation Serval the Central African Republic (CAR) to curb ethno-religious warfare. During a visit to to Barkhane three African nations in the summer of 2014, the French president announced Understanding France’s Operation Barkhane, a reorganization of Increased Involvement in troops in the region into a counter-terrorism Africa in the Context of force of 3,000 soldiers. In light of this, what is one to make Françafrique and Post- of Hollande’s promise to break with colonialism tradition concerning France’s African policy? To what extent has he actively Carmen Cuesta Roca pursued the fulfillment of this promise, and does continued French involvement in Africa constitute success or failure in this rançois Hollande did not enter office regard? France has a complex relationship amid expectations that he would with Africa, and these ties cannot be easily become a foreign policy president. F cut. This paper does not seek to provide a His 2012 presidential campaign carefully critique of President Hollande’s policy focused on domestic issues. Much like toward France’s former African colonies. Nicolas Sarkozy and many of his Rather, it uses the current president’s predecessors, Hollande had declared, “I will decisions and behavior to explain why break away from Françafrique by proposing a France will not be able to distance itself relationship based on equality, trust, and 1 from its former colonies anytime soon. solidarity.” After his election on May 6, It is first necessary to outline a brief 2012, Hollande took steps to fulfill this history of France’s involvement in Africa, promise. -

Report of the Secretary-General on the Situation in Mali

United Nations S/2016/1137 Security Council Distr.: General 30 December 2016 Original: English Report of the Secretary-General on the situation in Mali I. Introduction 1. By its resolution 2295 (2016), the Security Council extended the mandate of the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA) until 30 June 2017 and requested me to report on a quarterly basis on its implementation, focusing on progress in the implementation of the Agreement on Peace and Reconciliation in Mali and the efforts of MINUSMA to support it. II. Major political developments A. Implementation of the peace agreement 2. On 23 September, on the margins of the general debate of the seventy-first session of the General Assembly, I chaired, together with the President of Mali, Ibrahim Boubacar Keita, a ministerial meeting aimed at mitigating the tensions that had arisen among the parties to the peace agreement between July and September, giving fresh impetus to the peace process and soliciting enhanced international support. Following the opening session, the event was co-chaired by the Minister for Foreign Affairs, International Cooperation and African Integration of Mali, Abdoulaye Diop, and the Minister of State, Minister for Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation of Algeria, Ramtane Lamamra, together with the Under - Secretary-General for Peacekeeping Operations. In the Co-Chairs’ summary of the meeting, the parties were urged to fully and sincerely maintain their commitments under the agreement and encouraged to take specific steps to swiftly implement the agreement. Those efforts notwithstanding, progress in the implementation of the agreement remained slow. Amid renewed fighting between the Coordination des mouvements de l’Azawad (CMA) and the Platform coalition of armed groups, key provisions of the agreement, including the establishment of interim authorities and the launch of mixed patrols, were not put in place. -

Insurgency and Counterinsurgency Dynamics in Mali

MC Chartrand Map of Mali and neighbouring countries. Insurgency and Counterinsurgency Dynamics in Mali by Ismaël Fournier Ismaël Fournier is a former infantryman with the operations. Key to these groups’ freedom of movement and 3rd Battalion of the Royal 22nd Regiment, who deployed with them to freedom of action is their access to geographical lines of com- Bosnia in 2001, and then to Kabul and Kandahar in Afghanistan in munication and to the civilian population. The former allows 2004 and 2007 respectively. Severely wounded in an IED explosion insurgents to move from their bases of operation to their objec- during the latter deployment, and after multiple restorative surger- tives, the latter will provide intelligence, recruits, food, and, in ies, Ismaël made a professional change to the military intelligence some cases, safe havens for the insurgents. VEO leaders will branch. Since then, he completed a baccalaureate, a master’s frequently deploy overseers in the villages to control the popu- degree, and a PH. D from Laval University in history. Leaving the lation and impose their will on the villagers. In other instances, armed forces in 2019, he is currently employed by the Department insurgents will come and go as they please in undefended villages of National Defence as am analyst specializing in strategy and to preach radical Islam, impose Sharia law and collect whatever tactics related to insurgencies and counter-insurgencies. they require. Introduction Part of counterinsurgency (COIN) operations will aim to deny insurgents access to villages via the deployment of static security ince the launch of the Tuareg rebellion in 2012, forces that will remain in the populated areas to protect the civil- violent extremist organisations (VEOs) have been ians. -

Hafete” Tichereyene N-Oussoudare N-Akal, Moukina N-Alghafete Id Timachalene in Kel Tahanite Daghe Mali

Humanitarian Action at the Frontlines: Field Analysis Series Realities and Myths of the “Triple Nexus” Local Perspectives on Peacebuilding, Development, and Humanitarian Action in Mali By Emmanuel Tronc, Rob Grace, and Anaïde Nahikian June 2019 Acknowledgments The authors would like to offer their thanks to all individuals and organizations interviewed for this research. Special appreciation is also extended to the Malians who supported this paper through their translations of the Executive Summary into a number of languages. Finally, sincere gratitude is expressed to the Malians who have lent their time, insights, and perspectives to this work. About the Authors The authors drafted this paper for the Harvard Humanitarian Initiative’s Advanced Training Program on Humanitarian Action (ATHA), where Emmanuel Tronc is Senior Research Analyst, Rob Grace is Senior Associate, and Anaïde Nahikian is Program Manager. About the Humanitarian Action at the Frontlines: Field Analysis Series The Humanitarian Action at the Frontlines: Field Analysis Series is an initiative of the Advanced Training Program on Humanitarian Action (ATHA) at the Harvard Humanitarian Initiative (HHI). It aims to respond to the demand across the humanitarian sector for critical context analysis, dedicated case studies, sharing of practice in humanitarian negotiation, as well as overcoming access challenges and understanding local perspectives. This series is oriented toward generating an evidence base of professional approaches and reflections on current dilemmas in this area. Our analysts and researchers engage in field interviews across sectors at the country-level and inter-agency dialogue at the regional level, providing comprehensive and analytical content to support the capacity of humanitarian professionals in confronting and addressing critical challenges of humanitarian action in relevant frontline contexts. -

S/2019/868 Security Council

United Nations S/2019/868 Security Council Distr.: General 11 November 2019 Original: English Joint Force of the Group of Five for the Sahel Report of the Secretary-General I. Introduction 1. The present report is submitted pursuant to Security Council resolution 2391 (2017), in which the Council requested me, in close coordination with the States members of the Group of Five for the Sahel (G5 Sahel) (Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania and the Niger) and the African Union, to report on the activities of the Joint Force of the Group of Five for the Sahel. It provides an update since my report of 6 May 2019 (S/2019/371) on progress made in the operationalization of the Joint Force, international support for the Force, the implementation of the technical agreement signed between the United Nations, the European Union and G5 Sahel States in February 2018, challenges encountered by the Force and the implementation by the G5 Sahel States of a human rights and international humanitarian law compliance framework. 2. The period under review was marked by low-intensity activity by the Joint Force due to the rainy season, which hampered the movements of the Force, and the impact of persistent equipment and training shortfalls on its operations. In accordance with resolution 2391 (2017), international partners continued to mobilize in support of the G5 Sahel. The attack of 30 September on the Force’s base in Boulikessi, Mopti region, central Mali, inflicted heavy casualties. The terrorist group Jama'a Nusrat ul-Islam wa al-Muslimin (JNIM) claimed responsibility for the attack. -

DIRECTION NATIONALE DE L'hydraulique Région De

MINISTÈRE DE L’ÉNERGIE ET DE L’EAU DIRECTION NATIONALE DE L’HYDRAULIQUE SITUATION DES POINTS D’EAU MODERNES AU MALI à partir de l'inventaire national réalisé en décembre 2018 Région de GAO Ministère de l’Énergie et de l'Eau Direction Nationale de l'Hydraulique Région de GAO 4 Cercles 23 Communes 696 Villages Situation des points d'eau modernes 2580 Points d'eau 41% Taux d'équipement 28% Taux d'accès Taux d'accès dans la région de GAO Cercle Population EPEM Total EPEM fonctionnel Taux d'eq́ uipement Taux d'acces̀ ANSONGO 230 246 300 175 37 % 26 % BOUREM 180 480 161 68 27 % 12 % GAO 363 073 976 614 50 % 38 % MENAKA 114 421 167 76 40 % 21 % Région de GAO Taux d'accès dans le cercle de ANSONGO Légende Réseau hydrographique Routes nationales Taux de desserte 0% - 20% 20% - 40% 40% - 60% 60% - 80% 80% - 100% Situation Region de GAO Cercle de ANSONGO Population 230246 Nombre de communes 7 Points d'eau 504 Taux d'équipement 37% Taux d'accès 26% Données collectées : Décembre 2018 Région de GAO Taux d'accès dans le cercle de ANSONGO Commune Population EPEM Total EPEM fonctionnel Taux d'eq́ uipement Taux d'acces̀ ANSONGO 40133 68 41 60 % 41 % BARA 20577 87 38 85 % 60 % BOURRA 24150 34 24 53 % 39 % OUATTAGOUNA 43297 37 28 34 % 26 % TALATAYE 44843 7 5 4 % 3 % TESSIT 29716 46 26 27 % 16 % TIN HAMA 27530 21 13 21 % 16 % Cercle de ANSONGO Types de points d'eau dans la commune de ANSONGO Légende Village Réseau hydrographique Route nationale Type de point d'eau SAEP PMH Forage non équipé Puits citerne Puits moderne Situation Cercle de ANSONGO Commune de -

Mali Et Le Burkina Faso

SYNTHESE DES ALERTES Cluster Food security & Livelihoods Alerte: Ménaka 1 Type d’alerte: Mouvement de population suite à un conflit armé Causes du mouvement: Attaque du poste de sécurité du Gatia/MSA dans la localité de Teringuit au sud-ouest de 2 Ménaka par des individus armés non identifiés faisant 17 morts et 6 blessés. L’incident a eu lieu le 14 février et les communautés par crainte ont fui la localité par crainte du regain de violence. 3 Activités réalisées: Evaluation multisectorielle rapide réalisée par l’équipe NRC/IRC/SLDSES du 28 février au 05 mars. Ciblage de 433 ménages déplacés. Assistance en cours de ces ménages en NFI (NRC) et de l’Aquatabs (Unicef) 4 Gap à couvrir : Assistance en vivres Sites de départ : Localité de Teringuit au sud ouest de Ménaka 5 Sites d’accueil: Chagam, Amintikiss, Intikinit, Tinibchi, Tinamamallolene I, Bazoum , Efankache, Chouggou, Tafeydakoute, Tinfassassane, Tingassane, Taborack, Akalafa, Tigalalene, Foga, Inerane, Gama, Inahale et Takoufouft, Tanekar, Tibinkar, Tibinkar, cercle et région de Ménaka Nombre de ménages affectés et ciblés: 433 3 Alerte: Ménaka 1 Type d’alerte : Mouvement de population suite aux opérations militaires Causes du mouvement : Opérations héliportées menées par les forces de la Barkhane au sud ouest de Ménaka sur des 2 positions des groupes extrémistes dans le village de Tagararte à 90 km de Ménaka ville le 01er mars. Les opérations se seraient poursuivies jusqu’au 03 mars dans le village de Tinzouragane avec des combats terrestres. D’autres affrontement ont eu lieu du 10 au 11 mars. Les mouvements sont toujours en cours. -

Africa Yearbook

AFRICA YEARBOOK AFRICA YEARBOOK Volume 10 Politics, Economy and Society South of the Sahara in 2013 EDITED BY ANDREAS MEHLER HENNING MELBER KLAAS VAN WALRAVEN SUB-EDITOR ROLF HOFMEIER LEIDEN • BOSTON 2014 ISSN 1871-2525 ISBN 978-90-04-27477-8 (paperback) ISBN 978-90-04-28264-3 (e-book) Copyright 2014 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Brill Nijhoff, Global Oriental and Hotei Publishing. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Koninklijke Brill NV provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, MA 01923, USA. Fees are subject to change. This book is printed on acid-free paper. Contents i. Preface ........................................................................................................... vii ii. List of Abbreviations ..................................................................................... ix iii. Factual Overview ........................................................................................... xiii iv. List of Authors ............................................................................................... xvii I. Sub-Saharan Africa (Andreas Mehler, -

Read the Executive Summary

16 Crossing the wilderness: Europe and the Sahel Presidents of the G5 Sahel and France at the Press Conference of the Pau Summit Executive summary No promised land the substantial financial and military resources they are ploughing into the region. France and its European partners are locked in a long-term struggle to try to stabilise the The Sahel needs tough love from Europe - vast Sahel region, spanning from Mauritania to a strategy to encourage political dialogue, Chad, in which there will be no outright victory governance reforms, decentralisation, over jihadist-backed insurgents and tangible protecting civilians, better public services and progress is hard to measure. the empowerment of women and young people, alongside security assistance, rather than an Often described as France’s Afghanistan, the obsessive focus on counter-terrorism with a conflict risks becoming Europe’s Afghanistan. blind eye to corruption and rights abuses. It also needs international partners to deliver on the There is no promised land at the end of the pledges they make at high-profile conferences. wilderness. But the European Union and its member states can achieve a better outcome Eight years after France’s military intervention than the present deadly instability if they make at the request of the Malian government to more targeted, integrated and conditional use of repel Islamist-dominated armed groups Executive summary | Spring 2021 17 advancing rapidly through central Mali and Europe has major economic, political and possibly towards the capital, Bamako, the demographic interests; and security situation has deteriorated across the central Sahel region, especially in the so-called • the central position of the Sahel makes tri-border area where Mali, Burkina Faso and it a historic crossroads for migration and Niger meet. -

Under Attack

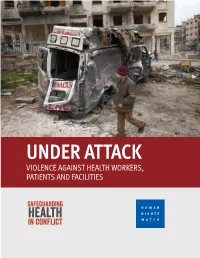

UNDER ATTACK V IOLEN CE A GA INST HEALTH WORKERS, PATIENTS AND FACILITIES Safeguarding HUMAN Health RIGHTS in Conflict WATCH (front cover) A Syrian youth walks past a destroyed ambulance in the Saif al-Dawla district of the war-torn northern city of Aleppo on January 12, 2013. © 2013 JM Lopez/AFP/Getty Images UNDER ATTACK VIOLENCE AGAINST HEALTH WORKERS, PATIENTS AND FACILITIES Overview of Recent Attacks on Health Care ...........................................................................................2 Introduction .......................................................................................................................................5 Urgent Actions Needed .......................................................................................................................7 Polio Vaccination Campaign Workers Killed ..........................................................................................8 Nigeria and Pakistan ......................................................................................................................8 Emergency Care Outlawed .................................................................................................................10 Turkey ..........................................................................................................................................10 Health Workers Arrested, Imprisoned ................................................................................................12 Bahrain ........................................................................................................................................12 -

What Next for Mali: Four Priorities for Better Governance in Mali

OXFAM BRIEFING NOTE 5 FEBRUARY 2014 Malian children in a Burkina Faso refugee camp, 2012. © Vincent Tremeau / Oxfam WHAT NEXT FOR MALI? Four priorities for better governance The 2013 elections helped to restore constitutional order in Mali and marked the start of a period of hope for peace, stability and development. The challenge is now to respond to the Malian people's desire for improved governance. The new government must, therefore, strive to ensure equitable development, increase citizen participation, in particular women's political participation, while improving access to justice and promoting reconciliation. INTRODUCTION Almost two years after the March 2012 coup d’état, the suspension of international aid that followed, and the occupation of northern Mali by armed groups, the Malian people now have a new hope for peace, development and stability. The recent presidential elections in July and August 2013 and parliamentary elections in November and December 2013 were a major step towards restoring constitutional order in Mali, with a democratically elected president and parliament. However, these elections alone do not guarantee a return to good governance. Major reforms are required to ensure that the democratic process serves the country's citizens, in particular women and men living in poverty. The Malian people expect to see changes in the way the country is governed; with measures taken against corruption and abuses of power by officials; citizens’ rights upheld, including their right to hold the state accountable; and a fairer distribution of development aid throughout the country. A new form of governance is needed in order to have a sustainable, positive impact on both the cyclical food crises that routinely affect the country and the consequences of the conflict in the north.