CPJ's Backgrounder on Pricing Carbon Emissions, Carbon and The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Weather Makers Re-‐Examined

THE WEATHER MAKERS RE-EXAMINED BIAS NEW RELEASE 400 page BOOK by Dr D W Allen Baseless Selection Reporting See details at bottom of spreadsheet Misinterpretation Misrepresentation Failed Preditions Failed Confusing / Silly Confusing Important Facts Important Suspect Source Suspect No uncertainty No Contradictory Exaggeration Factual Error Factual Half-truth Half-truth Dogmatic Flannery Statements Mistakes Extreme Allen Comments - mostly shortened Title - The Weather Makers Page 1 Weather is not climate / nature makes weather Climate change a threat to civilisation (R Purves) Foreword 1 Global cooling is the greater threat a theory is only valid for as long as it has not been disproved 2 1 Who could disprove that Tim will go to a special monkey heaven! Pollutants - known as greenhouse gases 3 1 Water vapour & CO2 pollutants? By 1975, the first sophisticated computer models 4 1 1 They were very primitive / still not sophisticated enough The heart of Earth's thermostat is CO2 5 1 Water is much more important the gas lasts around a century in the atmosphere 5 1 1 1 57% of it is naturally sequested within a year GHG reached levels not seen for millions of years 6 1 1 CO2 reached 348ppm during the early Holocene Replacing 4WD with a hybrid reduces GHG by 70% 6 1 1 It can actually increase global GHG emissions Vote for a politician who will sign Kyoto 8 1 Signing Kyoto in 2007 made no difference to emissions SECTION 1 - GAIA'S TOOLS Drop of 0.1% in solar radiation reaching Earth can trigger an 14 1 1 Compare with next statement ice age smog can cut sunlight by 10% and heat the lower environment Smoke (which is what he is referring to) blocks sunlight, cooling the 107 1 1 and ocean lower environment. -

Tim Flannery, the Weather Makers: the History and Future Impact of Climate Change

Tim Flannery, The Weather Makers: The History and Future Impact of Climate Change. Melbourne: Text Publishing, 2005. ISBN 1-920-88584-6 Paul Starr There are three modes of analysis in Tim Flannery’s recent climate change book: the historical, the diagnostic, and the prescriptive. The first two modes – charting the history of climate change, the history of climate science, and working out the parameters of our current predicament – take up almost all of the book. The move into prescription out of diagnosis, into what people can do to avoid or mitigate the impacts of climate change, happens in the last pages of the book, and this imbalance points to an important bind in which popular non-fiction writing about climate change for a general audience often finds itself. I will come back to this bind at the end of this review. Tim Flannery is well known in Australia, and to a lesser extent overseas, as a science- based provocateur. Earlier books based on his fieldwork in Papua New Guinea have drawn on archaeology and anthropology to explain issues such as biodiversity loss to a general audience. Books such as The Future Eaters and Throwim Way Leg contributed to popular debates on issues as diverse as the impacts of human cultures on historical ecosystems and the causes of past extinction events (such as those of Australian giant marsupials), through to the capacity of current societies to see how their behaviours contribute to, or detract from, the quality of human and non-human futures. Climate change was in many ways a new subject for Flannery. -

Thinking About Climate Change Change Climate About Thinking

THINKING ABOUT CLIMATE CHANGE A GUIDE FOR TEACHERS AND STUDENTS THINKING ABOUT THINKING ABOUT CLIMATE CHANGE A GUIDE FOR TEACHERS AND STUDENTS Written for teachers by teachers, this resource is designed to make teaching about climate change easy and accessible. It provides ideas for teachers in all states across key learning areas, and prepared worksheets appropriate for years 7–10. Including material drawn from Tim Flannery’s CLIMATE We Are the Weather Makers, it offers a valuable learning opportunity for students and will help develop both their thinking skills and understanding of climate change—the science, impacts and solutions. Also available online at www.theweathermakers.com NOT FOR SALE This is a free publication. Based on Tim Flannery’s CHAWE ARE THE A GUIDENG FOR TEACHERS AND STUDENTSE WEATHER MAKERS TEXT PUBLISHING COVER PHOTOGRAPH: GETTY IMAGES DESIGN: SUSAN MILLER THINKING ABOUT CLIMATE CHANGE A GUIDE FOR TEACHERS AND STUDENTS devised by: David Harding Rose Iser Sally Stevens TEXT PUBLISHING The Text Publishing Company Swann House 22 William Street Melbourne Victoria 3000 Australia www.textpublishing.com.au Copyright © Text Publishing 2007 Excerpts © Tim Flannery ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. All or part of this publication may be photocopied or printed providing it is for educational, non-profit purposes only. No part may be otherwise reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means electronic, mechanical or recording without the prior consent of the copyright owner and the publisher of this book. Book design & typesetting: Susan Miller Illustrations: Angela Ho Printed and bound in Australia by Print Bound NOT FOR SALE This is a free publication. -

Tim Flannery's

‘He can visualise our world in fifty years, and this vision haunts him’: Tim Flannery’s ‘Now or Never: A Sustainable Future for Australia?’1 Issue 9, December 2008 | David Hodgkinson If human beings follow a business-as-usual course, continuing to exploit fossil fuel resources without reducing carbon emissions or capturing and sequestering them before they warm the atmosphere, the eventual effects on climate and life may be comparable to those at the time of mass extinctions. Life will survive, but it will do so on a transformed planet. For all foreseeable human generations, it will be a far more desolate world than the one in which civilization developed and flourished during the past several thousand years. - Professor James Hansen, Director of the NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies and Adjunct Professor of Earth and Environmental Sciences, Earth Institute, Columbia University2 Until a few years ago Tim Flannery was best known for his book The Future Eaters,3 an ecological history of Australia. The Future Eaters is, in part, about the subtle interaction that makes an ecosystem work. It also presents an argument for sustainability, and climate change in a sustainability context has been the focus of Flannery’s work ever since. He was the Australian of the Year in 2007. In September 2008 Flannery appeared on Enough Rope with Andrew Denton, and Denton said to him: ‘Australian of the Year is not supposed to be political in his or her comments. Was it perhaps a useful place to put you, where you couldn’t be political?’4 He responded: ‘it might have been, but I sort of made it clear on the day that I got the Award that I wasn’t going to shut up. -

The Threat to the Planet by Jim Hansen

The Threat to the Planet By Jim Hansen The Weather Makers: How Man Is Changing the Climate and What It Means for Life on Earth by Tim Flannery Atlantic Monthly Press, 357 pp., $24.00 Field Notes from a Catastrophe: Man, Nature, and Climate Change by Elizabeth Kolbert Bloomsbury, 210 pp., $22.95 An Inconvenient Truth: The Planetary Emergency of Global Warming and What We Can Do About It by Al Gore Melcher Media/Rodale, 325 pp., $21.95 (paper) An Inconvenient Truth a film directed by Davis Guggenheim Jim Hansen is Director of the NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies and Adjunct Pro- fessor of Earth and Environmental Sciences at Columbia University’s Earth Institute. His opinions are expressed here, he writes, “as personal views under the protection of the First Amendment of the United States Constitution.” 1 1 Animals are on the run. Plants are migrating too. The Earth’s creatures, save for one species, do not have thermostats in their living rooms that they can adjust for an optimum environment. Animals and plants are adapted to specific climate zones, and they can survive only when they are in those zones. Indeed, scientists often define climate zones by the vegetation and animal life that they support. Gardeners and bird watchers are well aware of this, and their handbooks contain maps of the zones in which a tree or flower can survive and the range of each bird species. Those maps will have to be redrawn. Most people, mainly aware of larger day-to-day fluc- tuations in the weather, barely notice that climate, the average weather, is changing. -

Climate Change: Debate and Reality

CLIMATE CHANGE: DEBATE AND REALITY DANIEL R. HEADRICK Roosevelt University Abstract The debate about climate change has been raging for over 30 years. Is the climate really changing? If it is, are the changes caused by human actions? If they are, can anything be done about it? And, if so, should anything be done? On each of these questions, opinions clash. On one side are those who would say yes to all four questions. Among them are almost all climate scientists, most of the world’s governments and a large part of the educated public. On the other side are the current United States Government, most oil, gas and coal corporations, and most conservative politicians and their supporters, especially in the United States. It cannot be denied that the debate has caused confusion in the mind of the public—at least in the United States—and has helped prevent effective measures to mitigate global warming. In this essay, however, I argue that the impact of the debate pales in comparison to that of two other factors: developmentalism, the glorification of economic growth; and consumerism, the modern energy-intensive way of life. While the causes of the failure to mitigate global warming can be found in every country, the case of China is particularly glaring. Keywords: China, climate change, developmentalism, US Government Climate change: The evidence Among climate scientists, there is an almost complete consensus on the anthropogenic causes of global warming. All 928 articles on the subject published in refereed scientific journals between 1993 and 2003 agree on this point, as do the reports of the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the National Academy of Science, the American Meteorological Society, the American Geophysical Union and the American Association for the Advancement of Science. -

Climate Change Effects on Natural Resources

Climate Change Effects on Natural Resources FOR 797, Fall 2007 John Stella, [email protected] This seminar examined the evidence of global climate change, integrating scientific analyses and their perceptions in the media. Weekly class discussions focused on different physical, biological, Projected number of snow-covered days (Image: Union of Concerned Scientists) and social facets of the climate change story. Readings were drawn from primary climate change research (Nature, Science), global and regional analyses (IPCC 4th Assessment Report, New England Regional Assessment), news accounts, and the popular science literature (e.g. Tim Flannery’s The Weather Makers). For the final ‘White Paper’, students summarized the state of knowledge about a particular area, the perception of the issue in the media and popular literature, and the implications for policymakers. (Image: IPCC 2007) Muir Glacier, Alaska, 1941 and 2004 (Images: William Field, Bruce Molnia, USGS) FOR 797 Climate Change Effects on Natural Resources, Fall 2007 Final White Papers Table of Contents Chapter Subject Area Author Page 1 Overview: the physical science basis Katherina Searing 3 2 Paleoclimate and physical changes to the Matt Distler 10 atmosphere 3 Changes to the oceans Kacie Gehl 15 4 Changes to the cryosphere (snow, ice and frozen Brandon Murphy 19 ground) 5 Global and regional climate models Anna Lumsden 26 6 Impacts to freshwater resources Nidhi Pasi 31 7 Carbon sinks and sequestration Ken Hubbard 34 8 Impacts to coastal regions Juliette Smith 38 9 Effects on biodiversity and species ranges Lisa Giencke 43 10 Effects on species’ phenology Laura Heath 47 11 Human health, crop yields and food production Judy Crawford 52 12 Media perceptions of climate change: the Northeast Kristin Cleveland 57 case study 13 Mitigation measures Tony Eallonardo 62 INTRODUCTION Overview: the physical science Climate change is an extremely basis and expected impacts complex issue. -

The Weather Makers: How Man Is Changing the Climate and What It Means for Life on Earth Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE WEATHER MAKERS: HOW MAN IS CHANGING THE CLIMATE AND WHAT IT MEANS FOR LIFE ON EARTH PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Tim Flannery | 359 pages | 12 Dec 2006 | Grove Press / Atlantic Monthly Press | 9780802142924 | English | New York, United States The Weather Makers: How Man Is Changing the Climate and What It Means for Life on Earth PDF Book The book was first published in and updated in so it may becoming a bit dated in a quickly expanding subject area. The atmosphere has four distinct layers, which are defined on the basis of their temperature and the direction of their temperature gradient. In the mathematician James Lovelock published a book, Gaia, that delved deeply into these questions. The species he studies have been deeply impacted by climate changes to date, which means that global warming is not just something he decided to write a book about, but has been interested in for years, and that depth of interest is evident in the depth of evidence in the book. The author is from Australia so that country gets more coverage than one would otherwise expect. Although I haven't kept as close track on climate issues in the past couple of years, we seem to be on a mostly business-as-usual course, which makes for a certain amount of depressing reading. Nevertheless, it does provide a wealth of information that is rooted at the very beginning of the climate crisis and the basics will always be the same. For the first time, a scientist provided an accessible and comprehensive account of the history, current status, and future impact of climate change, writing what has been acclaimed by reviewers everywhere as the definitive book on global warming. -

Modeling the Impacts of Climate Change

ENVIRONMENTAL LITERACY TEACHER GUIDE SERIES Changing Climate A Guide for Teaching Climate Change in Grades 3 to 8 Modeling the Impacts 5 of Climate Change by Tara G Treiber odels help us understand model, the more accurate its predictions struggling to make sense of, such as the universe. They help us of the future will be. cloud and hurricane formation. Because M imagine things that are too Scientists often use computer-based of their complexity, many climate big, too small, too fast, or too slow for us models to help them understand what models are actually simulations in which to see directly. Models are representations is happening right now, as well as what multiple changing factors demonstrate, of phenomena and other concepts. might happen in the future. When all or “model,” how climate has changed and Most students are familiar with simple the pieces of a model are put together, continues to change over time. models, such as one they might make the model can run forward in time to Students may wonder how scientists of our solar system with coat hangers see what the future might look like or make predictions about rising and Styrofoam balls. Such a model helps backward in time to understand the past. temperatures or sea levels, so talking people envision events that happen on a Computer models of Earth’s global about climate models is necessary for size or time scale that they cannot easily climate system are complex. They their understanding. Most climate see. When the planets and sun of such include many data points that represent models today are created and run on a model are all properly arranged as parameters that intersect and interact high-performance computers capable they are in space, students can view how with one another. -

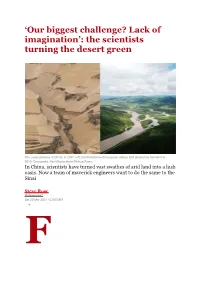

The Scientists Turning the Desert Green

‘Our biggest challenge? Lack of imagination’: the scientists turning the desert green The Loess plateau, in China, in 2007, left, and transformed into green valleys and productive farmland in 2019. Composite: Rex/Shutterstock/Xinhua/Alamy In China, scientists have turned vast swathes of arid land into a lush oasis. Now a team of maverick engineers want to do the same to the Sinai Steve Rose @steverose7 Sat 20 Mar 2021 12.00 GMT • F lying into Egypt in early February to make the most important presentation of his life, Ties van der Hoeven prepared by listening to the podcast 13 Minutes To The Moon – the story of how Nasa accomplished the lunar landings. The mission he was discussing with the Egyptian government was more earthbound in nature, but every bit as ambitious. It could even represent a giant leap for mankind. Van der Hoeven is a co-founder of the Weather Makers, a Dutch firm of “holistic engineers” with a plan to regreen the Sinai peninsula – the small triangle of land that connects Egypt to Asia. Within a couple of decades, the Weather Makers believe, the Sinai could be transformed from a hot, dry, barren desert into a green haven teeming with life: forests, wetlands, farming land, wild flora and fauna. A regreened Sinai would alter local weather patterns and even change the direction of the winds, bringing more rain, the Weather Makers believe – hence their name. “If anybody doubts that the Sinai can be regreened,” Van der Hoeven told the Egyptian delegates, an assortment of academics, representatives of ministers and military top brass, “then you have to understand that landing on the moon was once thought unrealistic. -

120 Ways to Combat Climate Change Revised 2021

120 WAYS YOU CAN COMBAT CLIMATE CHANGE Compiled by Robert Holt Originally Published 2009 Revised 2021 A compilation of suggestions from several sources Introduction Though the terms “global warming” and “climate change” sound innocuous, they denote the greatest crisis the civilized world has ever faced—literally! It has already begun: Arctic permafrost and sea ice are melting, as are the glaciers covering Greenland and Antarctica, starting a noticeable rise in sea level. Glaciers and snow-cover on mountains the world over are melting, too, contributing to disastrous shortages in water for drinking and agriculture. As the oceans become warmer and more acidic from the carbon dioxide (CO2) they absorb, drastic changes in sea life are caused; from tiny plankton to coral reefs to whales, many species are dying. Many thousands of people have already died, from heat waves, floods, droughts, and severe storms, but also from northward-moving tropical diseases. We don’t know how far we are from a tipping point, when the dark sea and soil exposed by melting ice and snow absorb much more heat, which will lead to more melting, releasing frozen methane, a greenhouse gas (GHG) 20+ times as powerful as CO2, then even more heating, in a vicious circle. Some global warming can be attributed to cyclic changes beyond human control, but hard data show that GHG, notably CO2 and methane, after centuries at a steady level, began a steady and accelerating rise in the atmosphere starting with the Industrial Revolution, fueled by coal, oil, natural gas, and other fossil fuels, followed by rising world temperature. -

Physical Impacts of Climate Change Resource List

Physical Impacts of Climate Change Resource list Books Tim Flannery “The Weather Makers: Our Changing Climate and what it means for Life on Earth” Robert Henson “The Rough Guide to Climate Change” Kirstin Dow “The Atlas of Climate Change” CDs Ross Harrison “Beyond the Brink” David Attenborough “The Truth about Climate Change” IISD Publications Centre “Inuit Observations on Climate Change” Websites http://climate.nasa.gov/effects/ this section of NASAs website focuses on global and regional physical impacts of climate change http://www.metoffice.gov.uk/climate-guide/science/uk/obs-projections-impacts shows impacts and provides information on the effects of climate change in the UK http://practicalaction.org/blog/programmes/climate_change/climate-change-diaries-sudan/ http://practicalaction.org/blog/programmes/climate_change/climate-change-diaries-kenya/ http://practicalaction.org/blog/programmes/climate_change/climate-change-diaries-zimbabwe/ use accounts from people in Zimbabwe, Kenya and the Sudan to work out some of the physical impacts of climate change http://wildgoose.ac/ a useful source of a range of resources including a range of types and sizes of world maps for the suggested activities, global warming photo packs http://wwf.panda.org WWF have a “toolkit” which examine the impacts of climate change on coasts and specifically marine turtles and their habitats in the Caribbean http://www.greenfacts.org/en/climate-change-ar4/l-3/4-observed-impacts.htm provides a summary of some of the physical impacts of climate change http://www.grist.org/article/2010-11-15-measuring-fast-melting-arctic-sea-ice a long article and discussion about the occurrence of ice melt as a result of climate change.