A KATP Channel Gene Effect on Sleep Duration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transcriptional and Post-Transcriptional Regulation of ATP-Binding Cassette Transporter Expression

Transcriptional and Post-transcriptional Regulation of ATP-binding Cassette Transporter Expression by Aparna Chhibber DISSERTATION Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Pharmaceutical Sciences and Pbarmacogenomies in the Copyright 2014 by Aparna Chhibber ii Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank my advisor, Dr. Deanna Kroetz. More than just a research advisor, Deanna has clearly made it a priority to guide her students to become better scientists, and I am grateful for the countless hours she has spent editing papers, developing presentations, discussing research, and so much more. I would not have made it this far without her support and guidance. My thesis committee has provided valuable advice through the years. Dr. Nadav Ahituv in particular has been a source of support from my first year in the graduate program as my academic advisor, qualifying exam committee chair, and finally thesis committee member. Dr. Kathy Giacomini graciously stepped in as a member of my thesis committee in my 3rd year, and Dr. Steven Brenner provided valuable input as thesis committee member in my 2nd year. My labmates over the past five years have been incredible colleagues and friends. Dr. Svetlana Markova first welcomed me into the lab and taught me numerous laboratory techniques, and has always been willing to act as a sounding board. Michael Martin has been my partner-in-crime in the lab from the beginning, and has made my days in lab fly by. Dr. Yingmei Lui has made the lab run smoothly, and has always been willing to jump in to help me at a moment’s notice. -

Whole-Exome Sequencing Identifies Novel Mutations in ABC Transporter

Liu et al. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth (2021) 21:110 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-021-03595-x RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Whole-exome sequencing identifies novel mutations in ABC transporter genes associated with intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy disease: a case-control study Xianxian Liu1,2†, Hua Lai1,3†, Siming Xin1,3, Zengming Li1, Xiaoming Zeng1,3, Liju Nie1,3, Zhengyi Liang1,3, Meiling Wu1,3, Jiusheng Zheng1,3* and Yang Zou1,2* Abstract Background: Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP) can cause premature delivery and stillbirth. Previous studies have reported that mutations in ABC transporter genes strongly influence the transport of bile salts. However, to date, their effects are still largely elusive. Methods: A whole-exome sequencing (WES) approach was used to detect novel variants. Rare novel exonic variants (minor allele frequencies: MAF < 1%) were analyzed. Three web-available tools, namely, SIFT, Mutation Taster and FATHMM, were used to predict protein damage. Protein structure modeling and comparisons between reference and modified protein structures were performed by SWISS-MODEL and Chimera 1.14rc, respectively. Results: We detected a total of 2953 mutations in 44 ABC family transporter genes. When the MAF of loci was controlled in all databases at less than 0.01, 320 mutations were reserved for further analysis. Among these mutations, 42 were novel. We classified these loci into four groups (the damaging, probably damaging, possibly damaging, and neutral groups) according to the prediction results, of which 7 novel possible pathogenic mutations were identified that were located in known functional genes, including ABCB4 (Trp708Ter, Gly527Glu and Lys386Glu), ABCB11 (Gln1194Ter, Gln605Pro and Leu589Met) and ABCC2 (Ser1342Tyr), in the damaging group. -

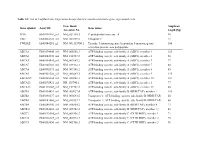

List of Taqman Gene Expression Assays That Were Used to Determine Gene Expression Levels

Table S1: List of TaqMan Gene Expression Assays that were used to determine gene expression levels Gene Bank Amplicon Gene symbol Assay ID Gene name Accession No. length [bp] PPIA Hs99999904_m1 NM_021130.3 Peptidylprolyl isomerase A 98 UBC Hs00824723_m1 NM_021009.5 Ubiquitin C 71 YWHAZ Hs03044281_g1 NM_001135700.1 Tyrosine 3-monooxygenase/tryptophan 5-monooxygenase 106 activation protein, zeta polypeptide ABCA1 Hs00194045_m1 NM_005502.3 ATP-binding cassette, sub-family A (ABC1), member 1 125 ABCA2 Hs00242232_m1 NM_212533.2 ATP-binding cassette, sub-family A (ABC1), member 2 58 ABCA3 Hs00184543_m1 NM_001089.2 ATP-binding cassette, sub-family A (ABC1), member 3 77 ABCA7 Hs00185303_m1 NM_019112.3 ATP-binding cassette, sub-family A (ABC1), member 7 80 ABCA8 Hs00992371_m1 NM_007168.2 ATP-binding cassette, sub-family A (ABC1), member 8 85 ABCA9 Hs00329320_m1 NM_080283.3 ATP-binding cassette, sub-family A (ABC1), member 9 145 ABCA10a Hs00365268_m1 NM_080282.3 ATP-binding cassette, sub-family A (ABC1), member 10 127 ABCA12 Hs00292421_m1 NR_103740.1 ATP-binding cassette, sub-family A (ABC1), member 1 77 ABCA13 Hs01110169_m1 NM_152701.3 ATP-binding cassette, sub-family A (ABC1), member 13 80 ABCB1 Hs00184491_m1 NM_000927.4 ATP-binding cassette, sub-family B (MDR/TAP), member 1 110 ABCB2 Hs00388677_m1 NM_000593.5 Transporter 1, ATP-binding cassette, sub-family B (MDR/TAP) 60 ABCB3 Hs00241060_m1 NM_018833.2 Transporter 2, ATP-binding cassette, sub-family B (MDR/TAP) 66 ABCB4 Hs00240956_m1 NM_018850.2 ATP-binding cassette, sub-family B (MDR/TAP), member -

Cardiovascular Diseases Genetic Testing Program Information

Cardiovascular Diseases Genetic Testing Program Description: Congenital Heart Disease Panels We offer comprehensive gene panels designed to • Congenital Heart Disease Panel (187 genes) diagnose the most common genetic causes of hereditary • Heterotaxy Panel (114 genes) cardiovascular diseases. Testing is available for congenital • RASopathy/Noonan Spectrum Disorders Panel heart malformation, cardiomyopathy, arrythmia, thoracic (31 genes) aortic aneurysm, pulmonary arterial hypertension, Marfan Other Panels syndrome, and RASopathy/Noonan spectrum disorders. • Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension (PAH) Panel Hereditary cardiovascular disease is caused by variants in (20 genes) many different genes, and may be inherited in an autosomal dominant, autosomal recessive, or X-linked manner. Other Indications: than condition-specific panels, we also offer single gene Panels: sequencing for any gene on the panels, targeted variant • Confirmation of genetic diagnosis in a patient with analysis, and targeted deletion/duplication analysis. a clinical diagnosis of cardiovascular disease Tests Offered: • Carrier or pre-symptomatic diagnosis identification Arrythmia Panels in individuals with a family history of cardiovascular • Comprehensive Arrhythmia Panel (81 genes) disease of unknown genetic basis • Atrial Fibrillation (A Fib) Panel (28 genes) Gene Specific Sequencing: • Atrioventricular Block (AV Block) Panel (7 genes) • Confirmation of genetic diagnosis in a patient with • Brugada Syndrome Panel (21 genes) cardiovascular disease and in whom a specific -

The Concise Guide to Pharmacology 2019/20: Transporters

University of Dundee The Concise Guide to Pharmacology 2019/20 CGTP Collaborators; Alexander, Stephen P. H.; Kelly, Eamonn; Mathie, Alistair; Peters, John A.; Veale, Emma L. Published in: British Journal of Pharmacology DOI: 10.1111/bph.14753 Publication date: 2019 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in Discovery Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): CGTP Collaborators, Alexander, S. P. H., Kelly, E., Mathie, A., Peters, J. A., Veale, E. L., ... Davies, J. A. (2019). The Concise Guide to Pharmacology 2019/20: Transporters. British Journal of Pharmacology, 176 (S1), S397- S493. https://doi.org/10.1111/bph.14753 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in Discovery Research Portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from Discovery Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain. • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 07. Dec. 2019 S.P.H. Alexander et al. The Concise -

ABCC9 Mutations Identified in Human Dilated Cardiomyopathy Disrupt

LETTERS ABCC9 mutations identified in human dilated cardiomyopathy disrupt catalytic KATP channel gating Martin Bienengraeber1,2, Timothy M Olson1,3, Vitaliy A Selivanov1, Eva C Kathmann1,2, Fearghas O’Cochlain1, Fan Gao2, Amy B Karger1,2, Jeffrey D Ballew1, Denice M Hodgson1, Leonid V Zingman1,2, Yuan-Ping Pang2, Alexey E Alekseev1,2 & Andre Terzic1,2 Stress tolerance of the heart requires high-fidelity metabolic sensing by ATP-sensitive potassium (KATP) channels that adjust a SUR2A Kir6.2 membrane potential–dependent functions to match cellular http://www.nature.com/naturegenetics energetic demand. Scanning of genomic DNA from individuals with heart failure and rhythm disturbances due to idiopathic COOH dilated cardiomyopathy identified two mutations in ABCC9, NBD1 NBD2 Exon 38 which encodes the regulatory SUR2A subunit of the cardiac KATP channel. These missense and frameshift mutations mapped to evolutionarily conserved domains adjacent to the catalytic Individual 1 Individual 2 V) ATPase pocket within SUR2A. Mutant SUR2A proteins showed 3 3 Normal Normal aberrant redistribution of conformations in the intrinsic ATP 2 2 hydrolytic cycle, translating into abnormal KATP channel 1 1 phenotypes with compromised metabolic signal decoding. Absorbance (m Absorbance (mV) 0 0 Defective catalysis-mediated pore regulation is thus a 345 345 Time (min) Time (min) mechanism for channel dysfunction and susceptibility to dilated cardiomyopathy. T A T T © 2004 Nature Publishing Group Asp A G Ter Val T T Val G T G Missense G T G T Normal mutation T Cardiac KATP channels are heteromultimers composed of Kir6.2, an Frameshift Cys G Normal mutation T Val Leu T T Leu inwardly rectifying potassium channel pore, and the regulatory T G C C SUR2A subunit, an ATPase-harboring ATP-binding cassette pro- G A C C Glu A G Gly Gly G G Gly 1–4 tein . -

1 Insights Into Transporter Classifications: an Outline Of

1 1 Insights into Transporter Classifications: an Outline of Transporters as Drug Targets Michael Viereck,1 Anna Gaulton,2 and Daniela Digles1 1University of Vienna, Department of Pharmaceutical Chemistry, Althanstrasse 14, 1090 Vienna, Austria 2EMBL – European Bioinformatics Institute, Wellcome Trust Genome Campus, Hinxton, Cambridge, CB10 1SD, UK 1.1 Introduction Classifications are a useful tool to get an overview of a topic. They show instan- ces grouped together that share common properties according to the creator of the classification, and as in the case of hierarchical classifications, they allow to draw conclusions on the relation of different classes. In the case of the identifica- tion of drug targets (including transporters as the main drug target), several pub- lications show classifications as a helpful tool. Imming et al. [1] categorized drugs according to their targets, to get an esti- mate on the number of known drug targets, including channels and transporters. Drugs on the market were connected to a target only if it was described as the main target in the literature. For transport proteins (including uniporters, sym- porters, and antiporters), this identified six different types of transporter groups that are relevant as drug targets. These are the cation-chloride cotransporter + + + + (CCC) family (SLC 12), Na /H antiporters (SLC 9), proton pumps, Na /K ATPases, the eukaryotic (putative) sterol transporter (EST) family, and the neu- + rotransmitter/Na symporter (NSS) family (SLC 6). These families mainly belong to either ATPases or solute carriers (SLC). Whether the EST family is treated as transport protein or not depends on the classification used. Rask-Andersen et al. -

Delineating the Role of Aedes Aegypti ABC Transporter Gene Family During Mosquito Development and Arboviral Infection Via Transcriptome Analyses

pathogens Article Delineating the Role of Aedes aegypti ABC Transporter Gene Family during Mosquito Development and Arboviral Infection via Transcriptome Analyses Vikas Kumar 1 , Shilpi Garg 1, Lalita Gupta 2, Kuldeep Gupta 3 , Cheikh Tidiane Diagne 4 , Dorothée Missé 4 , Julien Pompon 4 , Sanjeev Kumar 5,*,† and Vishal Saxena 1,*,† 1 Department of Biological Sciences, Birla Institute of Technology and Science (BITS), Pilani Campus, Pilani 333031, India; [email protected] or [email protected] (V.K.); [email protected] (S.G.) 2 Department of Zoology, Chaudhary Bansi Lal University, Bhiwani 127021, India; [email protected] or [email protected] 3 Department of Radiology and Radiological Sciences, School of Medicine, 470 Cancer Research Building-II, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD 21218, USA; [email protected] 4 MIVEGEC, Univ. Montpellier, IRD, CNRS, 34394 Montpellier, France; [email protected] (C.T.D.); [email protected] (D.M.); [email protected] (J.P.) 5 Department of Biotechnology, Chaudhary Bansi Lal University, Bhiwani 127021, India * Correspondence: [email protected] or [email protected] (S.K.); [email protected] (V.S.) † Both the authors contributed equally. Citation: Kumar, V.; Garg, S.; Gupta, L.; Gupta, K.; Diagne, C.T.; Missé, D.; Abstract: Aedes aegypti acts as a vector for several arboviral diseases that impose a major socio- Pompon, J.; Kumar, S.; Saxena, V. economic burden. Moreover, the absence of a vaccine against these diseases and drug resistance in Delineating the Role of Aedes aegypti mosquitoes necessitates the development of new control strategies for vector-borne diseases. -

Frequent Down-Regulation of ABC Transporter Genes in Prostate Cancer

Demidenko et al. BMC Cancer (2015) 15:683 DOI 10.1186/s12885-015-1689-8 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Frequent down-regulation of ABC transporter genes in prostate cancer Rita Demidenko1, Deividas Razanauskas1, Kristina Daniunaite1, Juozas Rimantas Lazutka1, Feliksas Jankevicius2,3 and Sonata Jarmalaite1* Abstract Background: ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters are transmembrane proteins responsible for the efflux of a wide variety of substrates, including steroid metabolites, through the cellular membranes. For better characterization of the role of ABC transporters in prostate cancer (PCa) development, the profile of ABC transporter gene expression was analyzed in PCa and noncancerous prostate tissues (NPT). Methods: TaqMan Low Density Array (TLDA) human ABC transporter plates were used for the gene expression profiling in 10 PCa and 6 NPT specimens. ABCB1 transcript level was evaluated in a larger set of PCa cases (N = 78) and NPT (N = 15) by real-time PCR, the same PCa cases were assessed for the gene promoter hypermethylation by methylation-specific PCR. Results: Expression of eight ABC transporter genes (ABCA8, ABCB1, ABCC6, ABCC9, ABCC10, ABCD2, ABCG2, and ABCG4) was significantly down-regulated in PCa as compared to NPT, and only two genes (ABCC4 and ABCG1) were up-regulated. Down-regulation of ABC transporter genes was prevalent in the TMPRSS2-ERG-negative cases. A detailed analysis of ABCB1 expression confirmed TLDA results: a reduced level of the transcript was identified in PCa in comparison to NPT (p = 0.048). Moreover, the TMPRSS2-ERG-negative PCa cases showed significantly lower expression of ABCB1 in comparison to NPT (p = 0.003) or the fusion-positive tumors (p = 0.002). -

ABCC9 Gene ATP Binding Cassette Subfamily C Member 9

ABCC9 gene ATP binding cassette subfamily C member 9 Normal Function The ABCC9 gene provides instructions for making the sulfonylurea receptor 2 (SUR2) protein. This protein forms one part (subunit) of a channel that transports charged atoms of potassium (potassium ions) across cell membranes. Each of these channels consists of eight subunits: four SUR2 proteins and four proteins produced from either the KCNJ8 or KCNJ11 gene. The SUR2 subunits regulate the activity of the channel, determining whether it is open or closed. Channels made with the SUR2 protein are known as ATP-sensitive potassium (K-ATP) channels. The channels open and close in response to the amount of ATP, the cell's main energy source, inside the cell. The resulting transport of potassium ions is part of a complex network of signals that relay chemical messages into and out of cells. Although K-ATP channels are present in cells and tissues throughout the body, the highest levels of SUR2-containing channels are found in skeletal and heart (cardiac) muscle. These channels indirectly help regulate the concentration of calcium ions in cells. This regulation is essential for normal heart function. The function of these channels in other tissues is unclear. Health Conditions Related to Genetic Changes Cantú syndrome At least 14 mutations in the ABCC9 gene have been found to cause Cantú syndrome, a rare condition characterized by excess hair growth (hypertrichosis), a distinctive facial appearance, and heart defects. Each of the mutations changes a single protein building block (amino acid) in the SUR2 protein. These changes likely alter the structure of the protein and its ability to regulate the activity of K-ATP channels. -

Genetic Determinants of COVID-19 Drug Efficacy Revealed by Genome-Wide

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.10.26.356279; this version posted October 27, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Genetic determinants of COVID-19 drug efficacy revealed by genome-wide CRISPR screens Wei Jiang1,7, Ailing Yang1,7, Jingchuan Ma1,7, Dawei Lv2, Mingxian Liu1, Liang Xu1, Chao Wang1, Zhengjin He1, Shuo Chen1, Jie Zhao1, Shishuang Chen1, Qi Jiang1, Yankai Chu1, Lin Shan1, Zhaocai Zhou3,4, Yun Zhao1,4,5, Gang Long6 and Hai Jiang1* Affiliations: 1 State Key Laboratory of Cell Biology, CAS Center for Excellence in Molecular Cell Science, Shanghai Institute of Biochemistry and Cell Biology, Chinese Academy of Sciences; University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, 320 Yueyang Road, Shanghai 200031, China 2 Institut Pasteur of Shanghai, Chinese Academy of Sciences; University of Chinese Academy of Sciences. 3 State Key Laboratory of Genetic Engineering, School of Life Sciences, Fudan University, Shanghai, 200438, China 4 School of Life Science and Technology, ShanghaiTech University, Shanghai, 201210, China 5 School of Life Science, Hangzhou Institute for Advanced Study, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Hangzhou 310024, China 6 CAS Key Laboratory of Molecular Virology & Immunology, Institut Pasteur of Shanghai, Chinese Academy of Sciences. 7 These authors contributed equally. *Corresponding should be addressed to H.J. ([email protected], ORCID Identifier: 0000-0002-2508-5413) bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.10.26.356279; this version posted October 27, 2020. -

Current Understanding of KATP Channels in Neonatal Diseases: Focus on Insulin Secretion Disorders

Acta Pharmacologica Sinica (2011) 32: 765–780 npg © 2011 CPS and SIMM All rights reserved 1671-4083/11 $32.00 www.nature.com/aps Review Current understanding of KATP channels in neonatal diseases: focus on insulin secretion disorders Yi QUAN1, Andrew BARSZCZYK1, Zhong-ping FENG1, *, Hong-shuo SUN1, 2, 3, 4, * Departments of 1Physiology, 2Surgery, and 3Pharmacology, 4Institute of Medical Science, Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto, 1 King’s College Circle, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M5S 1A8 ATP-sensitive potassium (KATP) channels are cell metabolic sensors that couple cell metabolic status to electric activity, thus regulat- ing many cellular functions. In pancreatic beta cells, KATP channels modulate insulin secretion in response to fluctuations in plasma glucose level, and play an important role in glucose homeostasis. Recent studies show that gain-of-function and loss-of-function muta- tions in KATP channel subunits cause neonatal diabetes mellitus and congenital hyperinsulinism respectively. These findings lead to sig- nificant changes in the diagnosis and treatment for neonatal insulin secretion disorders. This review describes the physiological and pathophysiological functions of KATP channels in glucose homeostasis, their specific roles in neonatal diabetes mellitus and congenital hyperinsulinism, as well as future perspectives of KATP channels in neonatal diseases. Keywords: ATP-sensitive potassium (KATP) channels; channelopathy; neonatal diabetes; congenital hyperinsulinism; glucose homeosta- sis; diazoxide; sulfonylureas Acta Pharmacologica Sinica (2011) 32: 765–780; doi: 10.1038/aps.2011.57; published online 23 May 2011 Introduction these diseases. It also discusses the current issues associated Adenosine triphosphate (ATP)-sensitive potassium (KATP) with the use of KATP channel modulators in treating these neo- channels function as metabolic sensors that are capable of natal diseases.