1 Chris Marker: a Grin Without a Cat Whitechapel Gallery, London, 16

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Constellation of Avant-Garde Cinemas and My Place in It Kuba

UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES ART AND DESIGN News From Elsewhere: A Constellation of Avant-Garde Cinemas and My Place in It Kuba Dorabialski MFA Research Paper School of Art and Design March 2017 1 ORIGINALITY STATEMENT ‘I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and to the best of my knowledge it contains no materials previously published or written by another person, or substantial proportions of material which have been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma at UNSW or any other educational institution, except where due acknowledgement is made in the thesis. Any contribu- tion made to the research by others, with whom I have worked at UNSW or elsewhere, is explicitly acknowledged in the thesis. I also declare that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work, except to the extent that assistance from others in the project's design and conception or in style, presentation and linguistic expression is acknowledged.’ Signed: Date: 27/03/2017 COPYRIGHT STATEMENT ‘I hereby grant the University of New South Wales or its agents the right to archive and to make available my thesis or dissertation in whole or part in the University libraries in all forms of media, now or here after known, subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. I retain all proprietary rights, such as patent rights. I also retain the right to use in future works (such as articles or books) all or part of this thesis or dissertation. I also authorise University Microfilms to use the 350 word abstract of my thesis in Dissertation Abstract International (this is applicable to doctoral theses only). -

The Book House

PETER BLUM GALLERY CHRIS MARKER Born 1921, Neuilly-sur-Seine, France Died 2012, Paris, France SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2019 Chris Marker: Cat Listening to Music. Video Art for Kids, Kunsthall Stavanger, Stavanger, Norway 2018 Chris Marker, Memories of the Future, BOZAR, Bruxelles, Belgium Chris Marker, Memories of the Future, Centre Pompidou, Paris, France Chris Marker, The 7 Lives of a Filmmaker, Cinémathèque Française, Paris, France Chris Marker: Koreans, Peter Blum Gallery at ADAA The Art Show, New York, NY 2016 DES (T/S) IN (S) DE GUERRE, Musée Zadkine, Paris, France 2014 Koreans, Peter Blum Gallery, New York, NY Crow’s Eye View: the Korean Peninsula, Korean Pavilion, Giardini di Castello, Venice, Italy Chris Marker: A Grin Without a Cat, Whitechapel Gallery, London, England; Kunstnernes Hus, Oslo, October 21, 2014 – January 11, 2015; Lunds Konsthall, Lund, February 7 – April 5, 2015 The Hollow Men, City Gallery Wellington, Wellington, New Zealand 2013 Chris Marker: Guillaume-en-Égypte, MIT List Visual Arts Center, Cambridge, MA & the Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA Memory of a Certain Time, ScotiaBank, Toronto, Canada Chris Marker, Atelier Hermès, Seoul, South Korea The “Planète Marker,” Centre de Pompidou, Paris, France 2012 Chris Marker: Films and Photos, Moscow Photobiennale, Moscow, Russia 2011 PASSENGERS, Peter Blum Gallery Chelsea / Peter Blum Gallery Soho, New York, NY Les Rencontres d'Arles de la Photographie, Arles, France PASSENGERS, Centre de la Photographie, Geneva, Switzerland -

Chris Marker (II)

Chris Marker (II) Special issue of the international journal / numéro spécial de la revue internationale Image [&] Narrative, vol. 11, no 1, 2010 http://ojs.arts.kuleuven.be/index.php/imagenarrative/issue/view/4 Guest edited by / sous la direction de Peter Kravanja Introduction Peter Kravanja The Imaginary in the Documentary Image: Chris Marker's Level Five Christa Blümlinger Montage, Militancy, Metaphysics: Chris Marker and André Bazin Sarah Cooper Statues Also Die - But Their Death is not the Final Word Matthias De Groof Autour de 1968, en France et ailleurs : Le Fond de l'air était rouge Sylvain Dreyer “If they don’t see happiness in the picture at least they’ll see the black”: Chris Marker’s Sans Soleil and the Lyotardian Sublime Sarah French Crossing Chris: Some Markerian Affinities Adrian Martin Petit Cinéma of the World or the Mysteries of Chris Marker Susana S. Martins Introduction Author: Peter Kravanja Article Pour ce deuxième numéro consacré à l'œuvre signé Chris Marker j'ai le plaisir de présenter aux lecteurs les contributions (par ordre alphabétique) de Christa Blümlinger, de Sarah Cooper, de Matthias De Groof, de Sylvain Dreyer, de Sarah French, d'Adrian Martin et de Susana S. Martins. Christa Blümlinger voudrait saisir le statut théorique des mots et des images « trouvées » que Level Five intègre dans une recherche « semi-documentaire », à l'intérieur d'un dispositif lié aux nouveaux médias. Vous pourrez ensuite découvrir la contribution de Sarah Cooper qui étudie le lien entre les œuvres d'André Bazin et de Chris Marker à partir de la fin des années 1940 jusqu'à la fin des années 1950 et au-delà. -

WILD Grasscert 12A (LES HERBES FOLLES)

WILD GRASS Cert 12A (LES HERBES FOLLES) A film directed by Alain Resnais Produced by Jean‐Louis Livi A New Wave Films release Sabine AZÉMA André DUSSOLLIER Anne CONSIGNY Mathieu AMALRIC Emmanuelle DEVOS Michel VUILLERMOZ Edouard BAER France/Italy 2009 / 105 minutes / Colour / Scope / Dolby Digital / English Subtitles UK Release date: 18th June 2010 FOR ALL PRESS ENQUIRIES PLEASE CONTACT Sue Porter/Lizzie Frith – Porter Frith Ltd Tel: 020 7833 8444/E‐Mail: [email protected] or FOR ALL OTHER ENQUIRIES PLEASE CONTACT Robert Beeson – New Wave Films – [email protected] 10 Margaret Street London W1W 8RL Tel: 020 3178 7095 www.newwavefilms.co.uk WILD GRASS (LES HERBES FOLLES) SYNOPSIS A wallet lost and found opens the door ‐ just a crack ‐ to romantic adventure for Georges (André Dussollier) and Marguerite (Sabine Azéma). After examining the ID papers of the owner, it’s not a simple matter for Georges to hand in the red wallet he found to the police. Nor can Marguerite retrieve her wallet without being piqued with curiosity about who it was that found it. As they navigate the social protocols of giving and acknowledging thanks, turbulence enters their otherwise everyday lives... The new film by Alain Resnais, Wild Grass, is based on the novel L’Incident by Christian Gailly. Full details on www.newwavefilms.co.uk 2 WILD GRASS (LES HERBES FOLLES) CREW Director Alain Resnais Producer Jean‐Louis Livi Executive Producer Julie Salvador Coproducer Valerio De Paolis Screenwriters Alex Réval Laurent Herbiet Based on the novel L’Incident -

Social Documentary in France from the Silent Era to the New Wave

Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature Volume 43 Issue 2 Article 42 October 2019 Steven Ungar. Critical Mass: Social Documentary in France from the Silent Era to the New Wave. U of Minnesota P, 2018. Mary McCullough Samford University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/sttcl Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons, and the French and Francophone Literature Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation McCullough, Mary (2019) "Steven Ungar. Critical Mass: Social Documentary in France from the Silent Era to the New Wave. U of Minnesota P, 2018.," Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature: Vol. 43: Iss. 2, Article 42. https://doi.org/10.4148/2334-4415.2105 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Steven Ungar. Critical Mass: Social Documentary in France from the Silent Era to the New Wave. U of Minnesota P, 2018. Abstract Review of Steven Ungar. Critical Mass: Social Documentary in France from the Silent Era to the New Wave. U of Minnesota P, 2018. Xxii + 300pp. Keywords Film, France, Documentary This book review is available in Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature: https://newprairiepress.org/sttcl/vol43/ iss2/42 McCullough: Review of Critical Mass Steven Ungar. Critical Mass: Social Documentary in France from the Silent Era to the New Wave. -

LE JOLI MAI the LOVELY MONTH of MAY a Film by Chris Marker & Pierre Lhomme an Icarus Films Release │ 1963 │ France │ 145 Mins │ 1.66:1 │ B&W │ DCP

LE JOLI MAI THE LOVELY MONTH OF MAY A film by Chris Marker & Pierre Lhomme An Icarus Films Release │ 1963 │ France │ 145 mins │ 1.66:1 │ B&W │ DCP “Mr. Marker has a penetrating camera and a penetrating mind. Both are employed with a searching persistence in this film, dissecting Paris, dissecting the people who live in Paris.” —Vincent Canby, The New York Times (1966) North American Theatrical Premiere Opens Sept. 13 at Film Forum, NYC; Sept. 20 at Laemmle’s Playhouse 7 and Royal Theaters, Los Angeles; Oct. 18 at Magic Lantern’s Carlton Cinema, Toronto; Oct. 27 at the Belcourt Theatre, Nashville; Nov. 8 at the Gene Siskel Film Center, Chicago; Nov. 9 at The Cinematheque, Vancouver; Nov. 15 at Landmark’s Opera Plaza and Shattuck Cinemas, San Francisco; Nov. 21 at O Cinema and Miami Beach Cinematheque, Miami; Dec. 6 at Landmark’s Kendall Square, Boston; and more! Icarus Films │ (718) 488-8900 │ 32 Court St. 21, Brooklyn, NY 11201 │ [email protected] ABOUT THE FILM Long unavailable in the U.S. and a major work in the oeuvre of filmmaker Chris Marker (1921-2012), LE JOLI MAI was awarded the International Critics Prize at the 1963 Cannes Film Festival and the “First Work” Prize at the 1963 Venice Film Festival. It premiered in North America in September 1963 at the first New York Film Festival. This restoration of LE JOLI MAI premiered at the Cannes Film Festival on May 16, 2013, 50 years after the film first premiered there. It was created according to the wishes of Marker, supervised by the film’s cinematographer and co-director, Pierre Lhomme (b. -

Review of Le Joli Mai

Chris Marker and Pierre Lhomme, Le Joli Mai, New York: Icarus Films, 2013/1963. 145 minutes; black and white In 1962 Chris Marker made two films that distilled post-war subterranean anxieties about the future. The better known of these, the elegiac 29-minute speculative fiction film, La Jetée, would captivate cinephiles and general audiences alike with its black and white tale of time travel, memory, lost love and apocalypse, assembling a series of still photographs to reinvent the very meaning of moving images while delicately reconstructing as fiction the latent terrors registered in the wake of cataclysmic world events. As fictional abstraction and a ground-breaking experiment with form and aesthetics, La Jetée would thoroughly eclipse the non-fiction film whose making constituted a real-world bedrock for La Jetée’s thematic preoccupations, Chris Marker and Pierre Lhomme’s foray into cinéma-vérité (or what Marker preferred to call “ciné, ma vérité” [“cinema, my truth”])1, Le Joli Mai. Filmed during “the lovely month” of May 1962, Le Joli Mai marked a departure for the elusive French filmmaker Chris Marker, who had become known within the post- war Parisian cultural scene for his personal and idiosyncratic travelogue films, including Letter from Siberia (1958) and Cuba Si! (1961). Pared-down from 55 hours of raw footage, Le Joli Mai is assembled mainly out of in-the-street interviews with a cross- section of “ordinary” Parisians, who are asked a variety of general questions about their lives, their relationships to work and the city, and their outlooks on the future. Their personal experiences are firmly situated in global geopolitics. -

Chris Marker Birth Name: Christian François Bouche-Villeneuve Director, Screenwriter, Cinematographer, Editor

Chris Marker Birth Name: Christian François Bouche-Villeneuve Director, Screenwriter, Cinematographer, Editor Birth Jul 29, 1921 (Neuilly-sur-Seine, France) Death Dec 24, 1997 (Tokyo, Japan Genres Avant-Garde/ Experimental Films A cinematic essayist and audio-visual poet, Chris Marker was one of the most innovative filmmakers to emerge during the postwar era. Working primarily in the arena of nonfiction, Marker rejected conventional narrative techniques, instead staking out a deeply political terrain defined by the use of still images, atmospheric soundtracks, and literate commentary. Adopting a perspective akin to that of a stranger in a strange land, his films — haunting meditations on the paradox of memory and the manipulation of time — investigated the philosophical implications of understanding the world through media and, by extension, explored the very definition of cinema itself. Born Christian François Bouche-Villeneuve on July 29, 1921, in Neuilly-sur- Seine, France, the intensely private and enigmatic Marker shrouded the personal details of his life in mystery. He rarely agreed to interviews, and during his rare tête-à-têtes with the media he was known to provide deliberate misinformation (as a result, some biographies even list him as a native of Outer Mongolia). It is known that during World War II, Marker joined the French Resistance forces (and also, according to myth, the U.S. Army). He later mounted a career as a writer and critic, publishing the novel Veillée de l'homme et de sa liberté in 1949. He also wrote 1952's Giraudoux par Lui-Même — an acclaimed study of the existential dramatist Jean Giraudoux, whose use of abstract narrative tools proved highly influential on Marker's subsequent film work — and appeared in the pages of Cahiers du Cinema. -

Bamcinématek Presents Chris Marker, a Retrospective of the Master Cine-Essayist, Aug 15—28

BAMcinématek presents Chris Marker, a retrospective of the master cine-essayist, Aug 15—28 Featuring the North American theatrical premiere of Level Five in a new restoration, Aug 15—21 The Wall Street Journal is the title sponsor for BAM Rose Cinemas and BAMcinématek. Brooklyn, NY/Jul 10, 2014—From Friday, August 15 through Thursday, August 28, BAMcinématek presents Chris Marker, a retrospective of the late auteur (1921—2012) whom Phillip Lopate dubbed “the one great cine-essayist in film history.” A sui generis cinema poet, French filmmaker and artist Marker used highly personal collages of moving images, photography, and text to explore weighty themes of time, memory, and political upheaval with a playful wit and an agile mind. Influenced by the Soviet montage style of editing, Marker rejected the label of cinéma vérité in favor of “ciné, ma vérité” (cinema, my truth), crafting witty, digressive, personal movies on a range of favorite subjects: history and memory, travel and Asia, animals, radical politics, filmmaking itself, and ultimately the whole of “what it’s like being on this planet at this particular moment” (Jonathan Rosenbaum, Chicago Reader). Born Christian François Bouche-Villeneuve, Marker took his pseudonym from the Magic Marker and remained an enigmatic figure throughout his career, eschewing interviews and photographs, present only and always in his films (and later CD-ROMs, Second Life, and other pioneering multimedia). Opening the series is the North American theatrical premiere run of Level Five (1996), screening from August 15—21 in a brand new restoration. Developing a video game about the Battle of Okinawa, a programmer (Catherine Belkhodja) becomes increasingly drawn into her work and haunted by her past in this provocative, retro-futuristic essay reflecting on the traumas of World War II and early internet culture. -

Jose Eduardo Kahale O Cinema Ensaio De Chris Marker: Narrativas Intertextuais Niterói 2013

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL FLUMINENSE INSTITUTO DE ARTES E COMUNICAÇÃO SOCIAL PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM COMUNICAÇÃO SOCIAL ESTUDOS DE CINEMA E AUDIOVISUAL JOSE EDUARDO KAHALE O CINEMA ENSAIO DE CHRIS MARKER: NARRATIVAS INTERTEXTUAIS NITERÓI 2013 JOSÉ EDUARDO KAHALE O CINEMA ENSAIO DE CHRIS MARKER: NARRATIVAS INTERTEXTUAIS Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Comunicação da Universidade Federal Fluminense, como requisito para obtenção do título de Mestre. Orientador: Prof. Dr. João Luiz Vieira Niterói Agosto//2013 ii K12 Kahale, José Eduardo. O cinema ensaio de Chris Marker: narrativas intertextuais / José Eduardo Kahale. – 2013. 193 f. ; il. Orientador: João Luiz Vieira. Dissertação (Mestrado em Comunicação) – Universidade Federal Fluminense, Instituto de Arte e Comunicação Social, 2013. Bibliografia: f. 181-186. 1. Cinema. 2. Ensaio. 3. Intertextualidade. 4. Level five (Filme). 5. Elegia a Alexandre (Filme). I. Vieira, João Luiz. II. Universidade Federal Fluminense. Instituto de Arte e Comunicação Social. III. Título. CDD 791.43 iii JOSÉ EDUARDO KAHALE O CINEMA ENSAIO DE CHRIS MARKER: NARRATIVAS INTERTEXTUAIS Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós- Graduação em Comunicação da Universidade Federal Fluminense, como requisito para obtenção do título de Mestre. Niterói, 2 de agosto de 2013 BANCA EXAMINADORA _____________________________________________ Prof. Dr. João Luiz Vieira – ORIENTADOR - UFF ______________________________________________ Prof. Dr. Cezar Migliorin –UFF ______________________________________________ Prof. Dr. Luiz Augusto de Rezende - UFRJ ___________________________________________ Prof. Dr. José Carlos Monteiro dos Santos – professor convidado - UFF Niterói, RJ 2013 iv Para minha esposa Claudine e minha filha Satya por todo amor, apoio e carinho que compartilhamos todos os dias de nossas vidas, e que me dão a força, a coragem e a alegria de viver na minha eterna busca pela felicidade e o autoconhecimento. -

La Petite Illustration Cinématographique : Chris Marker, Silent Movie, Starring Catherine Belkhodja

La petite illustration cinématographique : Chris Marker, Silent Movie, starring Catherine Belkhodja Author Marker, Chris, 1921-2012 Date 1995 Publisher Wexner Center for the Arts, The Ohio State University ISBN 1881390101 Exhibition URL www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/462 The Museum of Modern Art's exhibition history—from our founding in 1929 to the present—is available online. It includes exhibition catalogues, primary documents, installation views, and an index of participating artists. MoMA © 2017 The Museum of Modern Art ^WGRAP^Qo c Chris Marker Silent M o v i starring Catherine Belkhodja WEXNER CENTER for the ARTS THE OHIO STAT UNIVERSITY Acc ^ Museumof ModernArt Libra-? HoH<A I-721* Produced in association with Chris Marker: Silent Movie January 26—April 9, 1995 The Wexner Center presentation of SilentMovie has been Wexner Center for the Arts The Ohio State University made possible by a generous grant from The Andy Columbus, Ohio Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts. Major support June 21—September 12,1995 for the development of this project has been provided Museum of Modern Art New York, New York by a Wexner Center Residency Award, funded by the Wexner Center Foundation. January 10—March 10, 1996 University Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive Berkeley, California October 20, 1996—January 12, 1997 Walker Art Center Minneapolis, Minnesota Organized by William Horrigan, Wexner Center Curator of Media Arts. ©1995,Wexner Center for the Arts, SilentMovie is presented as part of the Motion Picture Centennial: Years of The Ohio State University Discovery, 1891—1896/ Years of Celebration 1991—1996,a six-year, nationwide, multi-institution observance of the first 100 years of the moving image arts. -

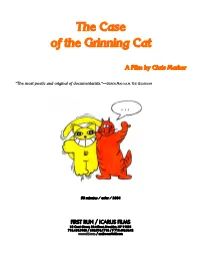

The Case of the Grinning Cat

The Case of the Grinning Cat A Film by Chris Marker "The most poetic and original of documentarists."—DEREK MALCOLM, THE GUARDIAN 58 minutes / color / 2004 FIRST RUN / ICARUS FILMS 32 Court Street, 21st Floor, Brooklyn, NY 11201 718.488.8900 / 800.876.1710 / F 718.488.8642 www.frif.com / [email protected] Synopsis The Case of the Grinning Cat, the latest creation from legendary French filmmaker Chris Marker, takes us meandering through Paris over the course of three years—2001 to 2004—ostensibly in search of a series of mysterious grinning cats whose stenciled image has sprung up in the most unlikely places: high atop buildings all over the city. The film—of which he has just prepared the English version—begins in November 2001 in a Paris still fresh from the shock of the September 11 attacks on the U.S., and where newspaper headlines read "We are all Americans." Over the next year, in the lead-up to the Iraq war, the city's youth march in numerous demonstrations for all manner of causes as Marker continues his pursuit of the mysterious cats. He finds them again, to his surprise, showing up as the emblem of the new French youth movement. "Make cats not war!" street art is the flip side of the idealism and exuberance driving the young people marching in protests the likes of which Paris hasn't seen since the mythic events of May 1968. While at times it might seem that the spirit of idealism has survived intact, the filmmaker's observation of it is tempered.