Time in the Canyon by David Morrison

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Grand Canyon U.S

National Park Service Grand Canyon U.S. Department of the Interior Grand Canyon National Park Arizona Hualapai Tribe and Skywalk The Hualapai (WALL-uh-pie), the “People of the Tall Pines,” have lived in the Southwest for untold generations. Traditionally their homelands stretched from Grand Canyon to the Bill Williams River in west-central Arizona and from the Black Mountains bordering the Colorado River to the San Francisco Peaks. Pri- marily nomadic hunter-gathers, they also traded with nearby tribes. The Hualapai Reservation of just less than 1,000,000 acres (404,686 ha) was established in 1883. Today the tribe counts about 2,300 members. Peach Springs on Highway 66 is the tribal headquarters. The tribe operates a hotel, restaurant, and gift shop in Peach Springs. While limited ranching, timber harvest, and guided hunts provide some income, the tourist industry offers the best opportunity for employment of tribal members. The Skywalk at The Hualapai Tribe has chosen a site at the far The Skywalk, managed by the Hualapai Tribe and Grand Canyon West western end of Grand Canyon about 250 miles located on tribal lands, consists of a horseshoe- (400 km) by road, a five hour drive, from Grand shaped steel frame with glass floor and sides that Canyon Village to offer a variety of visitor services projects about 70 feet (21 m) from the canyon rim. including the Skywalk in a development called While the Skywalk is the most famous attraction Grand Canyon West. Food service is limited and at Grand Canyon West, tours also include other usually as part of a package tour. -

Hnlvsn the Journal of Grancl Canyon River Guides, Inc

tho GRAND nows CANYON hnlvsn the journal of Grancl Canyon River Guides, Inc. GUIDES volume 7 numl-rer I winter 1993/1994 ()lrl Sltarlv ost Qrcmd Canyon boaters know of BuzzHolmstrom's 1937 solo journey down the and Colorad"o Riuers. Many of you may haue read of his life and death in -lrilte Qreen I lr.r:rlap:ri Daq.,idLauender's River Runners of the Grand Canyon. If not, 1ou should, as we won' t reDeat most of the better known facts ,^tou'll find there . What we' d like to present are (i(lElS Sche<lule two unique perspectives of a mcm who may haorc been both the grearc* nqtural boatman to eL)er dip an oar on the Colorado, and the humblest. l-'irst /\i(l VinceWelcbtraoLelledthroughhisown,andBuzz's,natiueNorthwestinsearchof Buzz. Brad Dimock went through Buzz's onluminous jownal of his solo trip and pulled out some of the more St't'\':t reuealing and drscriptiue passages. The stories that f ollow will g1r,e Jou new insight into the legend and the man that is Buzz.. l)<'lrris F-lou's -l-ilnn(-r F-loocl Looking For Buzz Down the Colorado Vince Welch Buzz Holmstrom ;\tnrosltl-rcric OIf tics ll [arorn the beginning of my n1*937 BuziiHolmstrom took a rime there has h.s. job at Coqyille, Ii\'(' llye Bi() Rio ff on the river, utiwion fr& .a I been only one true Canyon Or{gan ga; staqfl to gti on.&boat trip. l)('('ong(-Sklnt hero for me. I did:ns{ kliow then that the figure of Buzz Holmstrom (l()r()t1arV Ryl)ass would come to carry the weight of He liaded' it opd,',:1ffi,iioiffi a, A, alone to Qrg.en Rjvsi, Sfry .bis seuen ()rill I Iist()ry 'l-riril lt<'storatiorr Tril rs S[1S and the Super Pl-rorrt' llanditr), nil, that the arl ing thing we call I did I lculllr Dcpartnlent not truly appreciate the va were a knowing that there is a place iue of their -l'raffic ,\ir Canyon. -

Colin Fletcher, the Complete Walker and Other Titles

Colin Fletcher, The Complete Walker and other titles Outdoors-Magazine.com http://outdoors-magazine.com Colin Fletcher, The Complete Walker and other titles Schwert - Skills and guides - Library - Publication: Thursday 3 August 2006 Description : The Complete Walker and Colin Fletcher's other nine books are reviewed. The author also weaves in some of his early backpacking experiences. Copyright (c) Outdoors-Magazine.com under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-Share Alike License Copyright © Outdoors-Magazine.com Page 1/21 Colin Fletcher, The Complete Walker and other titles This review will touch on Colin Fletchers works, classics of backpacking how-to and enjoyment. Colin had a profound impact on my early backpacking days and has remained one of my favorite authors. In some respects his work reminds me of Calvin Rutstrum...a couple of decades more modern, and instrumental in the new age of backpacking, but still having a mixture of how-to with wonderful books of dream trips that utilized his techniques. It is likely that most readers of this site are well acquainted with Fletcher's Complete Walker in at least one of its derivations, but his other less popular works are excellent in their own right and well worth seeking out. This review will touch on these ten publications: The Thousand Mile Summer in Desert and High Sierra The Man Who Walked Through Time The Complete Walker The Winds of Mara The New Complete Walker The Man from the Cave The Complete Walker III Secret Worlds of Colin Fletcher River: One Man's Journey Down the Colorado, Source to Sea The Complete Walker IV with Chip Rawlins Copyright © Outdoors-Magazine.com Page 2/21 Colin Fletcher, The Complete Walker and other titles Colin Fletcher Bookshelf My catalog But first a bit of background.... -

Havasu Canyon Watershed Rapid Watershed Assessment Report June, 2010

Havasu Canyon Watershed Rapid Watershed Assessment Report June, 2010 Prepared by: USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service University of Arizona, Water Resources Research Center In cooperation with: Coconino Natural Resource Conservation District Arizona Department of Agriculture Arizona Department of Environmental Quality Arizona Department of Water Resources Arizona Game & Fish Department Arizona State Land Department USDA Forest Service USDA Bureau of Land Management Released by: Sharon Megdal David L. McKay Director State Conservationist University of Arizona United States Department of Agriculture Water Resources Research Center Natural Resources Conservation Service Principle Investigators: Dino DeSimone – NRCS, Phoenix Keith Larson – NRCS, Phoenix Kristine Uhlman – Water Resources Research Center Terry Sprouse – Water Resources Research Center Phil Guertin – School of Natural Resources The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, gender, religion, age, disa bility, po litica l be lie fs, sexua l or ien ta tion, an d mar ita l or fam ily s ta tus. (No t a ll prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at 202-720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, Room 326W, Whitten Building, 14th and Independence Avenue, SW, Washington, D.C., 20250-9410 or call (202) 720-5964 (voice or TDD). USDA is an equal employment opportunity provider and employer. Havasu Canyon Watershed serve as a platform for conservation 15010004 program delivery, provide useful 8-Digit Hydrologic Unit information for development of NRCS Rapid Watershed Assessment and Conservation District business plans, and lay a foundation for future cooperative watershed planning. -

PUBLIC LAW 93-620-JAN. 3, 1975 2089 Otherwise Release

88 STAT.] PUBLIC LAW 93-620-JAN. 3, 1975 2089 otherwise release a person before trial or sentencing or pending appeal in a court of the United States, and "(2) the term 'offense' means any Federal criminal offense which is in violation of any Act of Congress and is triable by any court established by Act of Congress (other than a petty offense as defined in section 1 (3) of this title, or an offense triable by court- martial, military commission, provost court, or other military tribunal)." SEC. 202. The analysis of chapter 207 of title 18, United States Code, is amended by striking out the last item and inserting in lieu thereof the following: "3152. Establishment of Pretrial Services Agencies. "3153. Organization of Pretrial Services Agencies. "3154. Functions and Powers of Pretrial Services Agencies. "3155. Report to Congress. "3156. Definitions." SEC. 203. For the purpose of carrying out the provisions of this title Appropriation. and the amendments made by this title there is hereby authorized to be appropriated for the fiscal year ending June 30, 1975, to remain available until expended, the sum of $10,000,000, SEC. 204. Section 604 of title 28, United States Code, is amended by striking out paragraphs (9) through (12) of subsection (a) and inserting in lieu thereof: "(9) Establish pretrial services agencies pursuant to section 3152 of title 18, United States Code; Ante, p. 208(5. "(10) Purchase, exchange, transfer, distribute, and assign the custody of lawbooks, equipment, and supplies needed for the maintenance and operation of -

Thunder River Trail and Deer Creek

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Grand Canyon Grand Canyon National Park Arizona Thunder River Trail and Deer Creek The huge outpourings of water at Thunder River, Tapeats Spring, and Deer Spring have attracted people since prehistoric times and today this little corner of Grand Canyon is exceedingly popular among seekers of the remarkable. Like a gift, booming streams of crystalline water emerge from mysterious caves to transform the harsh desert of the inner canyon into absurdly beautiful green oasis replete with the music of falling water and cool pools. Trailhead access can be difficult, sometimes impossible, and the approach march is long, hot and dry, but for those making the journey these destinations represent something close to canyon perfection. Locations/Elevations Mileages Indian Hollow (6250 ft / 1906 m) to Bill Hall Trail Junction (5400 ft / 1647 m): 5.0 mi (8.0 km) Monument Point (7200 ft / 2196 m) to Bill Hall Junction: 2.6 mi (4.2 km) Bill Hall Junction, AY9 (5400 ft / 1647 m) to Surprise Valley Junction, AM9 (3600 ft / 1098 m): 4.5 mi ( 7.2 km) Upper Tapeats Camp, AW7 (2400 ft / 732 m): 6.6 mi ( 10.6 km) Lower Tapeats, AW8 at Colorado River (1950 ft / 595 m): 8.8 mi ( 14.2 km) Deer Creek Campsite, AX7 (2200 ft / 671 m): 6.9 mi ( 11.1 km) Deer Creek Falls and Colorado River (1950 ft / 595 m): 7.6 mi ( 12.2 km) Maps 7.5 Minute Tapeats Amphitheater and Fishtail Mesa Quads (USGS) Trails Illustrated Map, Grand Canyon National Park (National Geographic) North Kaibab Map, Kaibab National Forest (good for roads) Water Sources Thunder River, Tapeats Creek, Deer Creek, and the Colorado River are permanent water sources. -

Grand Canyon

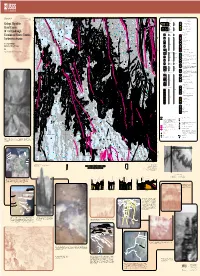

U.S. Department of the Interior Geologic Investigations Series I–2688 14 Version 1.0 4 U.S. Geological Survey 167.5 1 BIG SPRINGS CORRELATION OF MAP UNITS LIST OF MAP UNITS 4 Pt Ph Pamphlet accompanies map .5 Ph SURFICIAL DEPOSITS Pk SURFICIAL DEPOSITS SUPAI MONOCLINE Pk Qr Holocene Qr Colorado River gravel deposits (Holocene) Qsb FAULT CRAZY JUG Pt Qtg Qa Qt Ql Pk Pt Ph MONOCLINE MONOCLINE 18 QUATERNARY Geologic Map of the Pleistocene Qtg Terrace gravel deposits (Holocene and Pleistocene) Pc Pk Pe 103.5 14 Qa Alluvial deposits (Holocene and Pleistocene) Pt Pc VOLCANIC ROCKS 45.5 SINYALA Qti Qi TAPEATS FAULT 7 Qhp Qsp Qt Travertine deposits (Holocene and Pleistocene) Grand Canyon ၧ DE MOTTE FAULT Pc Qtp M u Pt Pleistocene QUATERNARY Pc Qp Pe Qtb Qhb Qsb Ql Landslide deposits (Holocene and Pleistocene) Qsb 1 Qhp Ph 7 BIG SPRINGS FAULT ′ × ′ 2 VOLCANIC DEPOSITS Dtb Pk PALEOZOIC SEDIMENTARY ROCKS 30 60 Quadrangle, Mr Pc 61 Quaternary basalts (Pleistocene) Unconformity Qsp 49 Pk 6 MUAV FAULT Qhb Pt Lower Tuckup Canyon Basalt (Pleistocene) ၣm TRIASSIC 12 Triassic Qsb Ph Pk Mr Qti Intrusive dikes Coconino and Mohave Counties, Pe 4.5 7 Unconformity 2 3 Pc Qtp Pyroclastic deposits Mr 0.5 1.5 Mၧu EAST KAIBAB MONOCLINE Pk 24.5 Ph 1 222 Qtb Basalt flow Northwestern Arizona FISHTAIL FAULT 1.5 Pt Unconformity Dtb Pc Basalt of Hancock Knolls (Pleistocene) Pe Pe Mၧu Mr Pc Pk Pk Pk NOBLE Pt Qhp Qhb 1 Mၧu Pyroclastic deposits Qhp 5 Pe Pt FAULT Pc Ms 12 Pc 12 10.5 Lower Qhb Basalt flows 1 9 1 0.5 PERMIAN By George H. -

South Kaibab Trail, Grand Canyon

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Grand Canyon Grand Canyon National Park Arizona South Kaibab Trail Hikers seeking panoramic views unparalleled on any other trail at Grand Canyon will want to consider a hike down the South Kaibab Trail. It is the only trail at Grand Canyon National Park that so dramatically holds true to a ridgeline descent. But this exhilarating sense of exposure to the vastness of the canyon comes at a cost: there is little shade and no water for the length of this trail. During winter months, the constant sun exposure is likely to keep most of the trail relatively free of ice and snow. For those who insist on hiking during summer months, which is not recommended in general, this trail is the quickest way to the bottom (it has been described as "a trail in a hurry to get to the river"), but due to lack of any water sources, ascending the trail can be a dangerous proposition. The South Kaibab Trail is a modern route, having been constructed as a means by which park visitors could bypass Ralph Cameron's Bright Angel Trail. Cameron, who owned the Bright Angel Trail and charged a toll to those using it, fought dozens of legal battles over several decades to maintain his personal business rights. These legal battles inspired the Santa Fe Railroad to build its own alternative trail, the Hermit Trail, beginning in 1911 before the National Park Service went on to build the South Kaibab Trail beginning in 1924. In this way, Cameron inadvertently contributed much to the greater network of trails currently available for use by canyon visitors. -

In This Issue USMC Wounded Warrior “A TALE of TWO BOATS”

Number Sixteen preserving public access to the Colorado River Winter, 2013 A Tale of Two Boats By Gaylord Staveley Based on excerpts from a forthcoming book on the human history of the Colorado River system and the Grand Canyon. Fifteen years after Major John Wesley Powell’s voyage of discovery down the mainstem Green and Colorado rivers and through Grand Canyon, a thirty year old trapper named Nathaniel Galloway began boating the smaller rivers that ran tributary to the Green in Utah, Wyoming and Colorado. In 1891 he tackled the rapids-filled gorges of Red Canyon, the Canyon of Lodore, a one hundred twenty-five mile section of the Green that end-runs the Uintas and comes back into the Uinta Basin near Vernal, Utah. After running those challenging waters a couple of times, he began looking for a new river. In 1895 he and a companion, probably one of his sons, ran the Green down to the head of Cataract Canyon and then rowed and dragged back upstream to Moab, Utah. In 1896, on a repeat run of the upper gorges, he encountered two prospectors who had gotten boat-wrecked in a formidable rapid called Ashley falls (now buried about two miles up-reservoir from Flaming Gorge Dam). Galloway and one of the men, William Richmond, decided to throw in together and run all the way down the rivers, as Powell had done. Trapping and prospecting as they went, it took them almost five months to go from Jensen, Utah to Needles, California, much of it in the dead of winter. -

Wes Hildreth

Transcription: Grand Canyon Historical Society Interviewee: Wes Hildreth (WH), Jack Fulton (JF), Nancy Brown (NB), Diane Fulton (DF), Judy Fierstein (JYF), Gail Mahood (GM), Roger Brown (NB), Unknown (U?) Interviewer: Tom Martin (TM) Subject: With Nancy providing logistical support, Wes and Jack recount their thru-hike from Supai to the Hopi Salt Trail in 1968. Date of Interview: July 30, 2016 Method of Interview: At the home of Nancy and Roger Brown Transcriber: Anonymous Date of Transcription: March 9, 2020 Transcription Reviewers: Sue Priest, Tom Martin Keys: Grand Canyon thru-hike, Park Service, Edward Abbey, Apache Point route, Colin Fletcher, Harvey Butchart, Royal Arch, Jim Bailey TM: Today is July 30th, 2016. We're at the home of Nancy and Roger Brown in Livermore, California. This is an oral history interview, part of the Grand Canyon Historical Society Oral History Program. My name is Tom Martin. In the living room here, in this wonderful house on a hill that Roger and Nancy have, are Wes Hildreth and Gail Mahood, Jack and Diane Fulton, Judy Fierstein. I think what we'll do is we'll start with Nancy, we'll go around the room. If you can state your name, spell it out for me, and we'll just run around the room. NB: I'm Nancy Brown. RB: Yeah. Roger Brown. JF: Jack Fulton. WH: Wes Hildreth. GM: Gail Mahood. DF: Diane Fulton. JYF: Judy Fierstein. TM: Thank you. This interview is fascinating for a couple different things for the people in this room in that Nancy assisted Wes and Jack on a hike in Grand Canyon in 1968 from Supai to the Little Colorado River. -

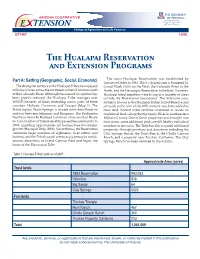

The Hualapai Reservation and Extension Programs

ARIZONA COOPERATIVE E TENSION College of Agriculture and Life Sciences AZ1467 10/08 The Hualapai Reservation and Extension Programs Part A: Setting (Geographic, Social, Economic) The main Hualapai Reservation was established by Executive Order in 1883. This U-shaped area is bordered by The aboriginal territory of the Hualapai Tribe encompassed Grand Wash Cliffs on the West, the Colorado River to the millions of acres across the northwest corner of Arizona south North, and the Havasupai Reservation to the East. However, of the Colorado River. Although this area of occupation has Hualapai tribal members were living in a number of areas been greatly reduced, the Hualapai Tribe manages over outside the Reservation boundaries. The Valentine area, 400,000 hectares of lands extending across parts of three formerly known as the Hualapai Indian School Reserve and counties: Mohave, Coconino, and Yavapai (Map 1). The set aside at the turn of the 20th century, was later added as Tribal capital, Peach Springs, is located on historic Route 66 trust land. Several tribal families continued to reside on midway between Seligman and Kingman. The Burlington traditional lands along the Big Sandy River in southeastern Northern Santa Fe Railroad travels on a line south of Route Mohave County. One of these properties was brought into 66. Construction of Interstate 40 bypassed the community in trust status, some additional lands are still held by individual 1978, impeding opportunities for tourism-based economic members in fee status. The Tribe has also acquired additional growth (Hualapai Tribe, 2006). Nevertheless, the Reservation properties through purchase and donations including the welcomes large numbers of sightseers, river rafters and Clay Springs Ranch, the Hunt Ranch, the Cholla Canyon hunters, and the Tribal capital serves as a gateway to world- Ranch, and a property near Truckee, California. -

Grand Canyon Celebration of Art 2018

GRAND CANYON CELEBRATION OF ART 2018 ra leb t i n e g c10 YEARS ra leb t i n e g c10 YEARS GRAND CANYON CELEBRATION OF ART 2018 Grand Canyon Association CONTENTS G R A N D C A N YO N A S S O C I A T I O N Post Office Box 399, Grand Canyon, AZ 86023 (800) 858-2808 www.grandcanyon.org Copyright © 2018 by Grand Canyon Association All Rights Reserved. Published 2018. All artwork are the property of their respective artists and are protected by copyright law. No portion of this book may be reproduced in whole or in part, by any means (with the exception of short quotes for the purpose of review), without permission of the publisher. Printed in the United States of America. i v FOREWORD BY 9 MICHELLE CONDRAT 19 JOHN LINTOTT JOSHUA ROSE Designed by Barbara Glynn Denney 1 0 BILL CRAMER 20 MICK McGINTY Edited by Mindy Riesenberg 1 TRIBUTE ISBN Number 978-1-934656-94-5 11 ROBERT DALEGOWSKI 21 JAMES McGREW Grand Canyon Association is the official nonprofit partner of Grand Canyon National 2 ABOUT GRAND CANYON 1 2 CODY DeLONG 22 MARCIA MOLNAR Park, raising private funds, operating retail shops within the park, and providing premier ASSOCIATION guided educational programs about the natural and cultural history of the region. Our supporters fund projects including trails and historic building preservation, educational 3 SUZIE BAKER 1 3 ROBERT GOLDMAN 23 CLYDE “ROSS” MORGAN programs for the public, and the protection of wildlife and their natural habitat.