Adoption of E-Book Readers Among College Students: a Survey Nancy M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Exploring New Frontiers of Electronic Publishing in Biomedical Science

Distinguished Editors Series Singapore Med J 2009; 50 (3) : 230 50 years of publication Exploring new frontiers of electronic publishing in biomedical science Ng K H ABSTRACT • Fully searchable, navigable, retrievable, impact- Publishing is a hallmark of good scientific rankable research papers. research. The aim of publishing is to disseminate • Access to research data. new research knowledge and findings as widely • For free, for all, forever. as possible in a timely and efficient manner. Scientific publishing has evolved over the years EVOLUTION OF ELECTRONIC PUBLISHING with the advent of new technologies and demands. The term, “Electronic Publishing”, is primarily used This paper presents a brief discussion on the today to refer to the current practice of online and web- evolution and status of electronic publishing. based publishing. However, it is also used to describe the The Open Access Initiative was created with the development of new forms of production, distribution, and aim of overcoming various limitations faced by user interaction with regard to computer-based production traditional publishing access models. Innovations of text and other interactive media. Electronic publishing have opened up possibilities for electronic also includes the publication of ebooks and electronic publishing to increase the accessibility, visibility, articles, as well as the development of digital libraries and interactivity and usability of research. A glimpse catalogues.(4,5) of the future publishing landscape has revealed Electronic publishing has become common in scholarly that scientific communication and research will publications where it has been argued that this mode of not remain the same. The internet and advances in publishing is in the process of replacing peer reviewed information technology will have an impact on the scientific journals. -

Electronic Reading Devices: Are They Hurting Or Helping the Print Publishing Industry?

Electronic Reading Devices: Are They Hurting or Helping the Print Publishing Industry? by Savannah Nikkole Wesley B.A., Middle Tennessee State University, 2014 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Science Degree in Mass Communications Department of Mass Communications In the Graduate School Middle Tennessee State University March, 2014 DEDICATION I’d like to dedicate this paper to my son Jeremiah Eden Wesley. Jeremiah you are my inspiration and the reason I keep going and working hard to better myself. I hope that gaining my Master’s degree not only opens doors in my life, but in yours also. It is my sincerest hope that every moment spent away from you in writing this thesis only shows you how sacrifice and dedication to improving yourself can give you a brighter future. I love you my son. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would first like to thank Dr. Reineke for hours of invaluable assistance during the arduous research and writing portion of this paper. Additionally I sincerely appreciate all of my committee members for taking the time to give me your insights and feedback throughout this process. Finally, I’d like to thank Howard Books for three years of invaluable work and insight into many aspects of the publishing industry, which ultimately inspired the topic of this research thesis. iii Abstract With ever-evolving and emerging technology making an impact on today’s society, examining how this technology affects mass media is essential. This study attempts to delve into an emerging media - electronic reading devices - and research how they are changing the publishing industry by looking into the arenas of newspaper, magazine, and book publishing as well as at consumers of print media on a larger scale. -

E-Books: Understanding the Basics June 2009 by Jane Lee, California Digital Library

E-books: Understanding the Basics June 2009 by Jane Lee, California Digital Library What exactly is an e-book anyway? Before we can talk about ebooks and the issues surrounding them, we must define what an e- book is. This is not as easy as one may think. Although e-books appear in headlines with regular frequency these days, there is still confusion about what exactly an e-book is that makes it difficult to focus on the real issues. For many people, especially in the last few years, an e-book is a handheld device whose main purpose is to look and act like a book. For others, an e-book is a book that one can read on one’s computer. And for a growing number of people, an e-book is something that you can read on your PDA, smartphone, iPod, etc. E-books made their first big splash on the market a decade ago, but they didn’t quite catch on with the general public. PDAs were taking a foothold, and companies began developing software that allowed people to read books on them. Subscription services for e-books – NetLibrary, for example – have been available to library patrons who have access to the required platform. The first dedicated, handheld electronic reading device, the Rocket ebook, made its appearance in 19981, but it wasn’t until the release of the Sony Reader and Amazon’s Kindle that e-book readers seemed commercially viable2. The arguments and questions about e-books – about their past, present, and future – that people formulate are shaped by how they define e-books for themselves. -

The Electronic Book As a Disruptive Technology." Disrupting Society from Tablet to Tablet

Western Oregon University Digital Commons@WOU History of the Book: Disrupting Society from Student Scholarship Tablet to Tablet 6-2015 Chapter 14 - The lecE tronic Book as a Disruptive Technology Janel Chandler Western Oregon University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/history_of_book Part of the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Cultural History Commons, and the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons Recommended Citation Chandler, Janel. "The Electronic Book as a Disruptive Technology." Disrupting Society from Tablet to Tablet. 2015. CC BY-NC. This is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at Digital Commons@WOU. It has been accepted for inclusion in History of the Book: Disrupting Society from Tablet to Tablet by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@WOU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 14 The Electronic Book as a Disruptive Technology -Janel Chandler- In 2011, the United States made $90.3 million in the ebook market1. The electronic book, or ebook, is a book that is read on a computer or other electronic device2. Ebooks were invented in 1971 with Michael Hart’s “Project Gutenberg,” and Electronic books like the Nook and the Kindle have later took the world by storm in revolutionized the reading market1. 1998 with the invention of the ereader by Peanut Press2,3. Ebooks were originally just digital copies of books that someone typed up and put on the Internet. This new technology was a disruptive innovation because it granted instant availability, allowed for easier storage, was more convenient, and completely revolutionized the book market1. -

Electronic Books: How Digital Devices and Supplementary New Technologies Are Changing the Face of the Publishing Industry

Pub Res Q (2010) 26:219–235 DOI 10.1007/s12109-010-9178-z Electronic Books: How Digital Devices and Supplementary New Technologies are Changing the Face of the Publishing Industry Erin Carreiro Published online: 26 October 2010 Ó Safe Creative 2010 Abstract This paper explores the topic of electronic books (e-books) and the effect that these digital devices and other new technologies has on the publishing industry. Contemporary society often claims that the publishing industry is dying and that the innovation of the e-book will eventually sentence the printed book to death. But this study will show that such is not the case. While it is true that the world is undergoing a digital revolution, publishers today have not been left in the dust, because these firms have embraced electronic publishing (e-publishing). The invention of e-books opens a world of opportunities and since the e-book market is still in its growth stage, there is much work left to be done. As with any new venture, the industry faces certain challenges, such as piracy, but with tools like encryption, digital asset management (DAM), digital rights management (DRM), and digital object identifiers (DOI), publishers are well on the way to a solution. While it is safe to say that the digital revolution has forever changed the face of publishing, e-books could actually revitalize the industry. No one knows what the future of e-publishing will hold, but developments affect publishing houses, authors, and consumers alike. And while the ultimate fate of the printed book is yet unknown, for now, it is here to stay. -

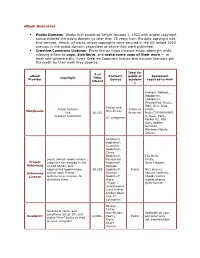

Ebook Resources Public Domain: Works First Published Before

eBook Resources Public Domain: Works first published before January 1, 1923 with proper copyright notice entered the public domain no later than 75 years from the date copyright was first secured. Hence, all works whose copyrights were secured in the US before 1923 are now in the public domain, regardless of where they were published. Creative Commons License: Every license helps creators retain copyright while allowing others to copy, distribute, and make some uses of their work — at least non-commercially. Every Creative Commons license also ensures licensors get the credit for their work they deserve. Ideal for # of eBook Content/ public or Equipment Copyright Titles Provider Genres academi required to view offered c Android, BeBook, Blackberry, eBookman, iPhone/iPod Touch, iPod, iRex, iLiad, Fiction and Public Domain Public or Kindle , Manybooks Non-Fiction and 26,021 Academic Nokia770/N800/N81 Creative Commons 0, Nook, Palm, 62 categories Pocket PC, PSP, Sony Reader, Symbian, Windows Mobile, Zaurus. Children's Bookshelf, Countries Bookshelf, Crime Bookshelf, The Nook, public domain books whose Periodicals Kindle, Project copyright has expired in the Bookshelf, Sony Ereader, Gutenberg United States, and Religion copyrighted books whose 30,000 Bookshelf, Public MP3 players, Gutenberg author gave Project Science gaming systems, License Gutenberg permission to Bookshelf, eBook readers, distribute them. Wars, mobile phones (Those 7 QiOO format. Subcategorie s are further broken down into 77 categories) Essays, Fiction, No area of terms and Non-Fiction, Readable on your conditions listed. Site just Readprint 8,000+ Poetry, Public computer only, states "Free" books to read Plays, not downloadable. on your computer. -

Die Neue Medialität Des Lesens: Ebooks Und Ebook- Reader“

DIPLOMARBEIT Titel der Diplomarbeit „Die neue Medialität des Lesens: eBooks und eBook- Reader“ Verfasserin Daniela Drobna, Bakk.a phil Angestrebter akademischer Grad Magistra der Philosophie (Mag. phil.) Wien, im Februar 2013 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 332 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Deutsche Philologie Betreuer: Assoz. Prof. Dr. Günther Stocker Inhaltsverzeichnis 1. Einleitung ............................................................................................................................... 1 2. Medientheoretische Einleitung ............................................................................................... 5 2.1. Definition Buch, eBook und eBook-Reader ...................................................................... 5 2.2. Medienevolution und Paradigmenwandel ....................................................................... 11 2.3. Medium und Medialität ................................................................................................... 18 2.4. Entwicklung von eBooks und eBook-Readern ............................................................... 22 2.5. Trends .............................................................................................................................. 26 3. Theorie der neuen Medialität des Lesens ............................................................................. 31 3.1. Paratexte .......................................................................................................................... 32 3.1.1. Typotopographie -

A Short History of Ebooks

A Short History of EBooks by Marie Lebert BIBLIOGRAPHIC RECORD Author Lebert, Marie Title A Short History of EBooks Language English LoC Class Z: Bibliography, Library science Subject Electronic books EText-No. 29801 Release Date 2009-08-26 Copyright Status Copyrighted work. See license inside work. Base Directory /2/9/8/0/29801/ The Project Gutenberg EBook of A Short History of EBooks, by Marie Lebert This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org ** This is a COPYRIGHTED Project Gutenberg eBook, Details Below ** ** Please follow the copyright guidelines in this file. ** Title: A Short History of EBooks Author: Marie Lebert Release Date: August 26, 2009 [EBook #29801] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK A SHORT HISTORY OF EBOOKS *** Produced by Al Haines A SHORT HISTORY OF EBOOKS MARIE LEBERT NEF, University of Toronto, 2009 Copyright © 2009 Marie Lebert. All rights reserved. --- This book is dedicated to all those who kindly answered my questions during ten years, in Europe, in America (the whole continent), in Africa, and in Asia. with many thanks for their time and their friendship. --- A short history of ebooks - also called digital books - from the first ebook in 1971 until now, with Project Gutenberg, Amazon, Adobe, Mobipocket, Google Books, the Internet Archive, and many others. This book is based on 100 interviews conducted worldwide and thousands of hours of web surfing during ten years. -

Electronic Publishing in Library and Information Science

Electronic Publishing in Library and Information Science JOEL M. LEE WILLIAM P. WHITELY ARTHUR W. HAFNER Definitions INTHE 1960s, PUBLISHERS BEGAN to use computers to support the produc- tion of directories, indexes, and other print publications. Computer assistance saved substantial time and money, and, in conjunction with software for information retrieval systems, gave birth to electronic pub- lishing. Directories, indexes, and other print publications that were produced electronically were then published, accessed, and used elec- tronically and became known as databases. Databases have had a profound impact on librarianship and have transformed both library user services and operations. Such client ser- vices as literature searching are now faster and more comprehensive. Library operations, like interlibrary loans and acquisitions, are now simpler and more effective. Machine-readable databases have also affected the dissemination of professional information. Librarians can find timely information about events and trends in librarianship in a number of databases. The focus of this paper will be those databases which support library operations and provide professional information. The reader should be aware, however, that databases are just one facet of electronic Joel M. Lee is Senior Manager, Information Technology Publishing, American Library Association, Chicago, Illinois; William P. Whitely is Director, Department of Marketing and Technical Services, Division of Library and Information Management, American Medical Association, Chicago, Illinois; and Arthur W. Hafner is Director, Division of Library and Information Management, American Medical Association, Chicago, Illinois. SPRING 1988 673 LEE & WHITELY & HAFNER publishing. Indeed, the term electronic publishing is used with little precision and may refer to a range of activities that include composing manuscripts, formatting pages, typesetting books, and producing data- bases. -

Are E-Books Effective Tools for Learning? Reading Speed and Comprehension: Ipad®I Vs

South African Journal of Education, Volume 35, Number 4, November 2015 1 Art. # 1202, 14 pages, doi: 10.15700/saje.v35n4a1202 Are e-books effective tools for learning? Reading speed and comprehension: iPad®i vs. paper Suzanne Sackstein, Linda Spark and Amy Jenkins Information Systems, Faculty of Commerce, Law and Management, University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa [email protected] Recently, electronic books (e-books) have become prevalent amongst the general population, as well as students, owing to their advantages over traditional books. In South Africa, a number of schools have integrated tablets into the classroom with the promise of replacing traditional books. In order to realise the potential of e-books and their associated devices within an academic context, where reading speed and comprehension are critical for academic performance and personal growth, the effectiveness of reading from a tablet screen should be evaluated. To achieve this objective, a quasi-experimental within- subjects design was employed in order to compare the reading speed and comprehension performance of 68 students. The results of this study indicate the majority of participants read faster on an iPad, which is in contrast to previous studies that have found reading from tablets to be slower. It was also found that comprehension scores did not differ significantly between the two media. For students, these results provide evidence that tablets and e-books are suitable tools for reading and learning, and therefore, can be used for academic work. For educators, e-books can be introduced without concern that reading performance and comprehension will be hindered. -

Designing and Publication of Interactive E-Book for Students of Princess Nourah Bint Abdulrahman University: an Empirical Study

Journal of Education and Practice www.iiste.org ISSN 2222-1735 (Paper) ISSN 2222-288X (Online) Vol.8, No.8, 2017 Designing and Publication of Interactive E-Book for Students of Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University: An Empirical Study Hessah Alshaya Afnan Oyaid Educational Technology, College of Education, Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Saudi Arabia Abstract The present study aims to keep pace with the rapid developments in the field of e-learning which includes the widespread use of e-books. Therefore, the authors conducted a pilot study on (55) faculty members from various disciplines, they assured the importance of e-books in education and the need for them. Accordingly, the authors designed and published their book "Education Technology: Foundations and Applications" as an interactive application on apps platforms by using a design model that was developed by the authors, and by adopting a list of (28) standards divided into four domains to ensure the quality of the design and development of the e-book according to educational and technological standards. Thereafter, female students’ perceptions of the effectiveness of e-books and their self-efficacy in using it were identified by (44) female students of Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University. The results indicate that the students have the basic skills necessary to download and read e-books and take advantage of its characteristics, additionally, they believe in its usefulness and are satisfied with it as they intend to continue using e-books in the future. Keywords : Designing. Publication, interactive, e-book, Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University 1. Introduction The present time is marked by constant change and rapid technological development which led to the emergence of many new technologies, contributed to the increase of flexibility rates of learning in terms of time and space, the speed and ease access to various learning materials, such as electronic textbooks. -

Lectores De Documentos Electrónicos

Eloísa Monteoliva, Carlos Pérez-Ortiz y Rafael Repiso Lectores de documentos electrónicos Por Eloísa Monteoliva, Carlos Pérez-Ortiz y Rafael Repiso Resumen: Se repasa la evolu- ción histórica de los dispositivos lectores de documentos electró- nicos (EReaders), y se describen las tecnologías del llamado papel electrónico. Se analizan el Gyri- con, las pantallas electroforéti- cas y las que utilizan el principio de electrohumedecimiento. Se presenta la variedad de formatos de archivo compatibles con los distintos dispositivos, así como los problemas que generan. Se describen los principales mode- Eloísa Monteoliva-García, Carlos Pérez-Ortiz, es licen- Rafael Repiso-Caballero, los disponibles en el mercado y es licenciada en traducción ciado en traducción e inter- es licenciado en documen- sus prestaciones, y se invita a la e interpretación, especializa- pretación. Sus especialidades tación por la Universidad de reflexión sobre su uso y efectivi- da en la traducción jurídica, son la traducción de textos Granada. Becario del Grupo económica y comercial e in- científicos y técnicos, y sus EC3, ha participado en los dad, la difusión de documentos, terpretación de conferencias lenguas de trabajo el inglés proyectos In-Recs e In-Recj. Es así como sobre las expectativas en inglés, alemán y francés. y el francés. Es director del documentalista de la Escuela creadas por los e-lectores que, a Investiga la interpretación en departamento del Dpto. de Superior de Comunicación día de hoy, ya hacen posible la los servicios públicos. Es tra- Relaciones Externas de ESCO (ESCO), Granada. ductora, intérprete y profeso- desde 2004, así como traduc- lectura ágil y cómoda de docu- ra de inglés en ESCO.