Rotary Printing Press (Edited from Wikipedia)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SUMMARY PLAN DESCRIPTION the Hearst Corporation Retirement Plan Contents

SUMMARY PLAN DESCRIPTION The Hearst Corporation Retirement Plan Contents THE HEARST CORPORATION RETIREMENT PLAN................................................................................1 LIFE EVENTS AND THE RETIREMENT PLAN...........................................................................................2 IMPORTANT DEFINITIONS.........................................................................................................................3 WHEN PARTICIPATION BEGINS ...............................................................................................................5 TRANSFERS.................................................................................................................................................6 CREDITED SERVICE AND VESTING SERVICE ........................................................................................6 IF YOU BECOME DISABLED...........................................................................................................................6 IF YOU TAKE AN APPROVED LEAVE OF ABSENCE...........................................................................................7 IF YOU TAKE A MILITARY LEAVE OF ABSENCE ...............................................................................................7 WHEN YOU DO NOT EARN CREDITED SERVICE.............................................................................................7 SPECIAL VESTING........................................................................................................................................7 -

The 2020 Election 2 Contents

Covering the Coverage The 2020 Election 2 Contents 4 Foreword 29 Us versus him Kyle Pope Betsy Morais and Alexandria Neason 5 Why did Matt Drudge turn on August 10, 2020 Donald Trump? Bob Norman 37 The campaign begins (again) January 29, 2020 Kyle Pope August 12, 2020 8 One America News was desperate for Trump’s approval. 39 When the pundits paused Here’s how it got it. Simon van Zuylen–Wood Andrew McCormick Summer 2020 May 27, 2020 47 Tuned out 13 The story has gotten away from Adam Piore us Summer 2020 Betsy Morais and Alexandria Neason 57 ‘This is a moment for June 3, 2020 imagination’ Mychal Denzel Smith, Josie Duffy 22 For Facebook, a boycott and a Rice, and Alex Vitale long, drawn-out reckoning Summer 2020 Emily Bell July 9, 2020 61 How to deal with friends who have become obsessed with 24 As election looms, a network conspiracy theories of mysterious ‘pink slime’ local Mathew Ingram news outlets nearly triples in size August 25, 2020 Priyanjana Bengani August 4, 2020 64 The only question in news is ‘Will it rate?’ Ariana Pekary September 2, 2020 3 66 Last night was the logical end 92 The Doociness of America point of debates in America Mark Oppenheimer Jon Allsop October 29, 2020 September 30, 2020 98 How careful local reporting 68 How the media has abetted the undermined Trump’s claims of Republican assault on mail-in voter fraud voting Ian W. Karbal Yochai Benkler November 3, 2020 October 2, 2020 101 Retire the election needles 75 Catching on to Q Gabriel Snyder Sam Thielman November 4, 2020 October 9, 2020 102 What the polls show, and the 78 We won’t know what will happen press missed, again on November 3 until November 3 Kyle Pope Kyle Paoletta November 4, 2020 October 15, 2020 104 How conservative media 80 E. -

San Francisco Chronicle a Division of Hearst Communications, Inc

San Francisco Chronicle A Division of Hearst Communications, Inc. Internet Advertising Agreement STANDARD TERMS & CONDITIONS These standard terms and conditions are hereby made part of the attached Contract/Agreement a. The printed image size of ads may vary from the mechanical measurements as a (the “Advertising Agreement”) by and between the San Francisco Chronicle/SFGate, a Division of result of production parameters and processing shrinkage. Hearst Communications, Inc., (“HEARST Media Services”) and the Advertiser named therein and party thereto (“Advertising Party”) and its advertising agency, if any (“Advertising Agency”, and b. All display advertisements are billed from cut off rule to cut off rule. For in column together with Advertising Party, “Advertiser”). Each such party acknowledges that the following ads, there is a charge for one cut off rule per liner ad. additional terms and conditions are incorporated in and made a part of the Advertising Agreement. c. Standard size advertisements over 19.5 inches in depth and tabloid size advertisements over 11 inches in depth will be charged full column depth of 21.5 A. ADVERTISING ACCEPTANCE/AGREEMENTS/RATES/COPY REGULATIONS inches and 11.5 inches respectively. 1. All advertising is accepted subject to HEARST Media Services’ approval. The HEARST Media Services shall at all times have the right without liability to reject, in whole or in 10. Display advertisements will be positioned from the bottom of the page. No guarantee is part, any advertisement scheduled to appear on the internet or in the newspaper for any made regarding positioning. Orders specifying positions are accepted only on a request reason in HEARST Media Services’ sole discretion, even if such advertisement has basis, subject to the right of the HEARST Media Services to determine actual positions previously been acknowledged or accepted. -

US Mainstream Media Index May 2021.Pdf

Mainstream Media Top Investors/Donors/Owners Ownership Type Medium Reach # estimated monthly (ranked by audience size) for ranking purposes 1 Wikipedia Google was the biggest funder in 2020 Non Profit Digital Only In July 2020, there were 1,700,000,000 along with Wojcicki Foundation 5B visitors to Wikipedia. (YouTube) Foundation while the largest BBC reports, via donor to its endowment is Arcadia, a Wikipedia, that the site charitable fund of Lisbet Rausing and had on average in 2020, Peter Baldwin. Other major donors 1.7 billion unique visitors include Google.org, Amazon, Musk every month. SimilarWeb Foundation, George Soros, Craig reports over 5B monthly Newmark, Facebook and the late Jim visits for April 2021. Pacha. Wikipedia spends $55M/year on salaries and programs with a total of $112M in expenses in 2020 while all content is user-generated (free). 2 FOX Rupert Murdoch has a controlling Publicly Traded TV/digital site 2.6M in Jan. 2021. 3.6 833,000,000 interest in News Corp. million households – Average weekday prime Rupert Murdoch Executive Chairman, time news audience in News Corp, son Lachlan K. Murdoch, Co- 2020. Website visits in Chairman, News Corp, Executive Dec. 2020: FOX 332M. Chairman & Chief Executive Officer, Fox Source: Adweek and Corporation, Executive Chairman, NOVA Press Gazette. However, Entertainment Group. Fox News is owned unique monthly views by the Fox Corporation, which is owned in are 113M in Dec. 2020. part by the Murdoch Family (39% share). It’s also important to point out that the same person with Fox News ownership, Rupert Murdoch, owns News Corp with the same 39% share, and News Corp owns the New York Post, HarperCollins, and the Wall Street Journal. -

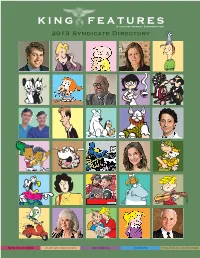

2013 Syndicate Directory

2013 Syndicate Directory NEW FEATURES CUSTOM SERVICES EDITORIAL COMICS POLITICAL CARTOONS What’s New in 2013 by Norman Feuti Meet Gil. He’s a bit of an underdog. He’s a little on the chubby side. He doesn’t have the newest toys or live in a fancy house. His parents are split up – his single mother supports them with her factory job income and his father isn’t around as often as a father ought to be. Gil is a realistic and funny look at life through the eyes of a young boy growing up under circumstances that are familiar to millions of American families. And cartoonist Norm Feuti expertly crafts Gil’s world in a way that gives us all a good chuckle. D&S From the masterminds behind Mobilewalla, the search, discovery and analytics engine for mobile apps, comes a syndicated weekly column offering readers both ratings and descriptions of highly ranked, similarly themed apps. Each week, news subscribers receive a column titled “Fastest Moving Apps of the Week,” which is the weekly hot list of the apps experiencing the most dramatic increases in popularity. Two additional “Weekly Category” features, pegged to relevant news, events, holidays and calendars, are also available. 3TW Drs. Oz and Roizen give readers quick access to practical advice on how to prevent and combat conditions that affect overall wellness and quality of life. Their robust editorial pack- age, which includes Daily Tips, a Weekly Feature and a Q & A column, covers a wide variety of topics, such as diet, exercise, weight loss, sleep and much more. -

(1) the Hearst Corporation, (2) Hearst Communications, Inc., Jury Trial Demanded (3) Hearst Newspapers Partnership, L.P., (4) Hearst Newspapers Ii, Llc

Case 2:13-cv-00056-JRG-RSP Document 12 Filed 07/12/13 Page 1 of 10 PageID #: 166 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS MARSHALL DIVISION C4CAST.COM, INC., Plaintiff, v. Civil Action No. 2:13-cv-056 (1) THE HEARST CORPORATION, (2) HEARST COMMUNICATIONS, INC., JURY TRIAL DEMANDED (3) HEARST NEWSPAPERS PARTNERSHIP, L.P., (4) HEARST NEWSPAPERS II, LLC, Defendants. AMENDED COMPLAINT FOR PATENT INFRINGEMENT Plaintiff c4cast.com, Inc. (“c4cast” or “Plaintiff”) files this Amended Complaint for patent infringement against Defendants The Hearst Corporation (“Hearst Corp.”), Hearst Communications, Inc. (“Hearst Communications”), Hearst Newspapers Partnership, L.P. (“Hearst News”), and Hearst Newspapers II, LLC (“Hearst News II”) (collectively, “Defendants”) alleging as follows: PARTIES 1. Plaintiff c4cast.com, Inc. is a Delaware corporation having a principal place of business of 750 E. Walnut St., Pasadena, California 91101. 2. On information and belief, Defendant Hearst Corp. is a corporation organized and existing under the laws of the State of Delaware, with its principal place of business located at 214 North Tryon Street, Charlotte, NC 28202. On information and belief, Hearst Corp. may be Case 2:13-cv-00056-JRG-RSP Document 12 Filed 07/12/13 Page 2 of 10 PageID #: 167 served via its registered agent, The Corporation Trust Company, Corporation Trust Center 1209 Orange St., Wilmington, Delaware 19801. 3. On information and belief, Defendant Hearst Communications is a subsidiary of Hearst Corp. and a corporation organized and existing under the laws of the State of Delaware, with its principal place of business located at 300 West 57th St., New York, NY 10019. -

FCC Form 312 Pro Forma Assignment of Receive-Only Earth Station E170001 EXHIBIT E DESCRIPTION of PRO FORMA TRANSACTION

FCC Form 312 Pro Forma Assignment of Receive-Only Earth Station E170001 EXHIBIT E DESCRIPTION OF PRO FORMA TRANSACTION The instant Form 312 application serves as notification of the pro forma assignment of receive- only earth station license E170001 from KMBC Hearst Television Inc. (“KMBCHTV”) to Hearst Stations Inc. (“Hearst Stations”). KMBCHTV was also the licensee of television station KMBC-TV, Kansas City, Missouri, which has used the receive-only earth station registered under call sign E170001. A Media Bureau application on FCC Form 316 with respect to KMBC-TV was previously filed and granted, and the pro forma transaction was consummated a few years ago. We recognize that the instant notification application is being filed late, and we respectfully request that you please see the waiver request attached to this same application relating to the timing of the instant filing relative to the consummation of the pro forma transaction and the circumstances and context relating thereto. At the time of the pro forma transaction, KMBCHTV and Hearst Stations were both wholly owned subsidiaries of Hearst Television Inc. (“Hearst Television”). Hearst Television is (and was at all relevant times) owned by Hearst Broadcasting, Inc. (“HBI”); HBI is (and was at all relevant times) owned by Hearst Communications, Inc. (“Communications”); Communications is (and was at all relevant times) owned by Hearst Holdings, Inc. (“Holdings”); and Holdings is (and was at all relevant times) owned by The Hearst Corporation (“Hearst”). For corporate organizational -

FCC Form 312 WVTM Hearst Television Inc. E000732, E030231 1

FCC Form 312 WVTM Hearst Television Inc. E000732, E030231 EXHIBIT E Assignee Parties to the Application WVTM Hearst Television Inc. The following are the officers, directors, and sole shareholder of WVTM Hearst Television Inc., which is the proposed licensee of temporary fixed earth stations E000732 and E030231: Name and Address Citizenship Positional Interest % of Votes % of Total Assets Catherine A. Bostron c/o The Hearst Corporation USA Secretary None None New York, NY John J. Drain Senior Vice President, c/o Hearst Television Inc. USA None None Treasurer, and Director New York, NY David L. Kors c/o The Hearst Corporation USA Assistant Treasurer None None Charlotte, NC Larry M. Loeb c/o The Hearst Corporation USA Assistant Secretary None None New York, NY Warren K. McDonald c/o The Hearst Corporation USA Assistant Treasurer None None Charlotte, NC Jeana Stanley c/o Hearst Television Inc. USA Vice President, Finance None None New York, NY Jordan M. Wertlieb c/o Hearst Television Inc. USA President and Director None None New York, NY Hearst Properties Inc. Domestic c/o Hearst Television Inc. Shareholder 100% 100% Corp. New York, NY 1 FCC Form 312 WVTM Hearst Television Inc. E000732, E030231 Hearst Properties Inc. The following are the officers, directors, and sole shareholder of Hearst Properties Inc.: Name and Address Citizenship Positional Interest % of Votes % of Total Assets David W. Abel President & General c/o Hearst Television Inc. USA None None Manager, WMTW New York, NY Jeffrey Bartlett President & General c/o Hearst Television Inc. USA None None Manager, WMUR-TV New York, NY Catherine A. -

Hearst Corporation - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Hearst Corporation - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hearst_Corporation Hearst Corporation From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia The Hearst Corporation is an American multinational conglomerate group based in the Hearst Tower in Hearst Corporation Midtown Manhattan, New York City. Founded by William Randolph Hearst as an owner of newspapers, the company has holdings that have subsequently expanded Type Private to include a highly diversified portfolio of media Industry Conglomerate[1] interests. The Hearst family is involved in the ownership Founded March 4, 1887 and management of the corporation. San Francisco, California, Hearst is one of the largest diversified communications United States companies in the world. Its major ownership interests Founder William Randolph Hearst include 15 daily and 36 weekly newspapers and more Headquarters Hearst Tower than 300 magazines worldwide, including Harper's Midtown Manhattan Bazaar, Cosmopolitan, Esquire, Elle, and O, The Oprah New York City, United States Magazine; 31 television stations through Hearst Key people William Randolph Hearst III Television, Inc., which reach a combined 20% of U.S. (Chairman) viewers; ownership in leading cable networks, including Frank A. Bennack, Jr. A+E Networks, and ESPN Inc.; as well as business (Executive Vice Chairman) publishing, digital distribution, television production, Steve Swartz newspaper features distribution, and real estate ventures. (President and CEO) Revenue US$ 10 billion (2014)[2][3] Contents Owner Hearst family -

Disney/Fox: Disney Proposes Divesting A&E Channels to Address European Commission Concerns

Vol. 6 No. 379 October 26, 2018 Disney/Fox: Disney Proposes Divesting A&E Channels to Address European Commission Concerns Deal Update Disney has proposed divesting the A&E Networks’ channels in Europe to allay competition enforcers’ concerns with its planned acquisition of 21st Century Fox, according to a source familiar with the matter. Under the divestiture proposal, Disney would retain the rights to use the trademarks and logos of the channels, according to the source. Disney submitted the offer on October 12 as part of the European Commission’s Phase I review of the transaction, in an effort to stave off an extended Phase II investigation that would extend into 2019. The commission sent out the proposal for market testing to a number of European downstream providers of television services on October 16, with responses due October 23. But at least one TV retailer has told the EC that the remedy as proposed would not solve its concerns that a combined Disney/Fox would wield too much power post merger in negotiations for the wholesale supply of TV channels, the source said. Television overlap. Although European television markets vary on a nation by nation basis, a combined Disney/Fox will control important channels in a number of national markets, sources said. In Germany, for example, Fox licenses FOX, National Geographic Channel, Nat Geo People, and Nat Geo Wild, the market’s third most popular pay-TV channel. Disney controls important channels in the German market, and licenses Disney Channel Germany on free TV, and Disney XD, Disney Junior and Disney Cinemagic on pay-TV. -

Carmen Paz Álvarez Enríquez Juez Árbitro NIC-Chile ______

Carmen Paz Álvarez Enríquez Juez Árbitro NIC-Chile __________________________________________________________________________________________ Sentencia definitiva Arbitraje por nombre de dominio harpersbazaar.cl Titular: GLORIYA KONSTANTINOVA Revocante: HEARST COMMUNICATIONS, INC. Rol N° 33817 Tipo de revocación: Temprana Santiago, 2 de mayo de 2020 VISTOS: PRIMERO: Que, con fecha 24 de febrero de 2020 se creó el expediente por el arbitraje electrónico relativo al nombre de dominio “harpersbazaar.cl” inscrito por GLORIYA KONSTANTINOVA, cuyo contacto administrativo es Gloriya Konstantinova (email: [email protected]); y cuyo Revocante es HEARST COMMUNICATIONS, INC., representado por don Bernardo Serrano Spoerer, abogado, ambos domiciliados para estos efectos en calle Avda. Alonso de Córdova Nº 5151, piso 8, comuna de Las Condes, Santiago; SEGUNDO: Que, habiéndose abierto la etapa de tachas, éstas se presentaron en tiempo y forma por la parte Revocante; TERCERO: Que, mediante oficio Nº 202003021221-33817 de fecha 2 de marzo de 2020, el Centro de Resolución de Controversias de NIC Chile comunicó a la suscrita su designación como árbitro para resolver el conflicto suscitado por la presentación de la solicitud de revocación del nombre de dominio “harpersbazaar.cl”; CUARTO: Que, con fecha 2 de marzo de 2019 la suscrita aceptó el nombramiento como árbitro y juró desempeñar fielmente el cargo, con la debida diligencia y en el menor tiempo posible; QUINTO: Que, ninguna de las partes solicitó la inhabilidad de esta juez árbitro en el período señalado, el que de acuerdo al sistema de NIC Chile finalizó con fecha 10 de marzo de 2020; SEXTO: Que, con fecha 18 de marzo de 2020 se efectuó la consignación de los honorarios arbitrales por parte de HEARST COMMUNICATIONS, INC., la que realizó en tiempo y forma; SÉPTIMO: Que, por escrito de fecha 27 de marzo de 2020, HEARST COMMUNICATIONS, INC. -

Local Bay Area & State

San Francisco Chronicle and SFGate.com Monday, October 12, 2020 Local Bay Area & State FRONT PAGE Fix seeks to right leaning building $100 million project to repair S.F. Millennium By J.K. Dineen our years after the Millen- nium Tower grabbed interna- tional attention as the world’s most prominent sinking and Fleaning high-rise, the off-kilter condo tower is set to start a $100 million fix that residents hope will not only cor- rect the engineering blunders of the past but restore values in the belea- guered building. Over the next few weeks, the scaf- folding will be erected at 301 Mission St. The sidewalks will be barricaded off. Pile drivers will start drilling the first of 52 concrete, 140,000-pound piles that will anchor the building to bedrock 250 feet below ground. The two-year project will relieve stress on soils that Photo: Lea Suzuki/The Chronicle have compressed beneath the building, The Millennium Tower is set to start a $100 million fix to correct the engineering contributing to its unwelcome and un- problems and restore home values, which dropped when it was found the build- anticipated sinking. Disruption to cur- ing was sinking in 2016. rent residents is expected to be minor. “This plan halts settlement along Fremont and Mission Streets while al- lowing the building to level itself over ects without adequate scrutiny. ing. Values plummeted. Banks stopped time,” said engineer Ronald Hamburg- Perhaps the city’s poshest luxury lending to the few buyers willing to er of Simpson Gumpertz & Heger, who condo tower when it opened in April take a chance in the building.