Videotelephony and Video Relay Service Policies Affecting US

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The History of the Telephone

STUDENT VERSION THE HISTORY OF THE TELEPHONE Activity Items There are no separate items for this activity. Student Learning Objectives • I will be able to name who invented the telephone and say why that invention is important. • I will be able to explain how phones have changed over time. THE HISTORY OF THE TELEPHONE STUDENT VERSION NAME: DATE: The telephone is one of the most important inventions. It lets people talk to each other at the same time across long distances, changing the way we communicate today. Alexander Graham Bell, the inventor of the telephone CENSUS.GOV/SCHOOLS HISTORY | PAGE 1 THE HISTORY OF THE TELEPHONE STUDENT VERSION 1. Like many inventions, the telephone was likely thought of many years before it was invented, and by many people. But it wasn’t until 1876 when a man named Alexander Graham Bell, pictured on the previous page, patented the telephone and was allowed to start selling it. Can you guess what “patented” means? CENSUS.GOV/SCHOOLS HISTORY | PAGE 2 THE HISTORY OF THE TELEPHONE STUDENT VERSION 2. The picture below, from over 100 years ago, shows Alexander Graham Bell using one of his first telephones to make a call from New York to Chicago. Alexander Graham Bell making a telephone call from New York to Chicago in 1892 Why do you think it was important that someone in New York could use the telephone to talk to someone in Chicago? CENSUS.GOV/SCHOOLS HISTORY | PAGE 3 THE HISTORY OF THE TELEPHONE STUDENT VERSION 3. Today, millions of people make phone calls each day, and many people have a cellphone. -

“It's Good for Them but Not So for Me”: Inside the Sign Language

“It’s good for them but not so for me”: Inside the sign language interpreting call centre The InternationalInternational Journal Journal for for Translation & Int&erpreting Interpreting Research trans-int.org-int.org Jemina Napier Heriot-Watt University, Scotland [email protected] Robert Skinner Heriot-Watt University, Scotland [email protected] Graham H. Turner Heriot-Watt University, Scotland [email protected] DOI: 10.12807/ti.109202.2017.a01 Abstract: This paper reports on findings from an international survey of sign language interpreters who have experience of working remotely via video link, either in a video relay service or as a video remote interpreter. The objective of the study was to identify the common issues that confront interpreters when working in these remote environments and ascertain what aspects of interpreting remotely via a video link are working successfully. The international reach of this survey demonstrates how working remotely via video link can be an integral part of bringing about social equality for deaf sign language users; yet according to interpreters who work in these services, ineffective video interpreting policies, poor public awareness and lack of training are identified as areas needing improvement. Keywords: video remote interpreting, sign language, interpreter experiences, interpreter perspectives, survey research 1. Introduction Due to the advent of technology, an increasing number of interpreter-mediated interactions are now taking place via the use of video. Interpreters are increasingly required to be involved in: (i) video conference interpreting (VCI), where there are two locations and the interpreter is in either one; or (ii) remote interpreting (RI), where all participants are together in one location and the interpreter is in a separate, remote location. -

![TELEPHONE TRAINING GUIDE] Fall 2010](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8505/telephone-training-guide-fall-2010-238505.webp)

TELEPHONE TRAINING GUIDE] Fall 2010

[TELEPHONE TRAINING GUIDE] Fall 2010 Telephone Training Guide Multi Button and Single Line Telephones Office of Information Technology, - UC Irvine 1 | Page [TELEPHONE TRAINING GUIDE] Fall 2010 Personal Profile (optional) ........................................... 10 Group Pickup (optional) ............................................... 10 Table of Contents Abbreviated Dialing (optional) ..................................... 10 Multi-Button Telephone General Description Automatic Call-Back ..................................................... 10 ....................................................................................... 3 Call Waiting .................................................................. 10 Keys and Buttons ............................................................ 3 Campus Dialing Instructions ............................ 11 Standard Preset Function Buttons .................................. 3 Emergency 911 ............................................................. 11 Sending Tones (TONE) .................................................... 4 Multi-Button Telephone Operations ................ 4 Answering Calls ............................................................... 4 Placing Calls .................................................................... 4 Transferring Calls ............................................................ 4 Inquiry Calls .................................................................... 4 Exclusive Hold ................................................................. 4 -

Telecommunications Provider Locator

Telecommunications Provider Locator Industry Analysis & Technology Division Wireline Competition Bureau February 2003 This report is available for reference in the FCC’s Information Center at 445 12th Street, S.W., Courtyard Level. Copies may be purchased by calling Qualex International, Portals II, 445 12th Street SW, Room CY- B402, Washington, D.C. 20554, telephone 202-863-2893, facsimile 202-863-2898, or via e-mail [email protected]. This report can be downloaded and interactively searched on the FCC-State Link Internet site at www.fcc.gov/wcb/iatd/locator.html. Telecommunications Provider Locator This report lists the contact information and the types of services sold by 5,364 telecommunications providers. The last report was released November 27, 2001.1 All information in this report is drawn from providers’ April 1, 2002, filing of the Telecommunications Reporting Worksheet (FCC Form 499-A).2 This report can be used by customers to identify and locate telecommunications providers, by telecommunications providers to identify and locate others in the industry, and by equipment vendors to identify potential customers. Virtually all providers of telecommunications must file FCC Form 499-A each year.3 These forms are not filed with the FCC but rather with the Universal Service Administrative Company (USAC), which serves as the data collection agent. Information from filings received after November 22, 2002, and from filings that were incomplete has been excluded from the tables. Although many telecommunications providers offer an extensive menu of services, each filer is asked on Line 105 of FCC Form 499-A to select the single category that best describes its telecommunications business. -

Video Relay Service: Program Funding and Reform

Video Relay Service: Program Funding and Reform Updated July 12, 2019 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R42830 Video Relay Service: Program Funding and Reform Summary The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) regulates a number of disability-related telecommunications services, including video relay service (VRS). VRS allows persons with hearing disabilities, using American Sign Language (ASL), to communicate with voice telephone users through video equipment rather than through typed text. VRS has quickly become a very popular service, as it offers several features not available with the text-based telecommunications relay service (TRS). The FCC has adopted various rules to maintain the quality of VRS service. Now VRS providers must answer 80% of all VRS calls within 120 seconds. VRS providers must also offer the service 24 hours a day, seven days a week. Additionally, in June 2010, the FCC began a comprehensive review of the rates, structure, and practices of the VRS program to minimize waste, fraud, and abuse and update compensation rates that had become inflated above actual cost. Rules in that proceeding were issued in June 2013. The new rules initiated fundamental restructuring of the program to support innovation and competition, drive down ratepayer and provider costs, eliminate incentives for waste, and further protect consumers. In addition, the new rules transition VRS compensation rates toward actual costs over the next four years, initiating a step-by-step transition from existing tiered TRS Fund compensation rates toward a unitary, market-based compensation rate. On June 28, 2019, the FCC adopted per-minute VRS compensation rates for the 2019-20 Fund Year, effective from July 1, 2019, through June 30, 2020. -

Dual Tone Multi Frequency (DTMF) Signal Generation and Detection Using MATLAB Software Nihat Pamuk Turkish Electricity Transmission Company, [email protected]

University of Business and Technology in Kosovo UBT Knowledge Center UBT International Conference 2015 UBT International Conference Nov 7th, 9:00 AM - 5:00 PM Dual Tone Multi Frequency (DTMF) signal generation and detection using MATLAB software Nihat Pamuk Turkish Electricity Transmission Company, [email protected] Ziynet Pamuk Sakarya University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://knowledgecenter.ubt-uni.net/conference Part of the Computer Sciences Commons, and the Digital Communications and Networking Commons Recommended Citation Pamuk, Nihat and Pamuk, Ziynet, "Dual Tone Multi Frequency (DTMF) signal generation and detection using MATLAB software" (2015). UBT International Conference. 97. https://knowledgecenter.ubt-uni.net/conference/2015/all-events/97 This Event is brought to you for free and open access by the Publication and Journals at UBT Knowledge Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in UBT International Conference by an authorized administrator of UBT Knowledge Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. International Conference on Computer Science and Communication Engineering, Nov 2015 Dual Tone Multi Frequency (DTMF) signal generation and detection using MATLAB software Nihat Pamuk1, Ziynet Pamuk2 1Turkish Electricity Transmission Company 2Sakarya University, Electric - Electronic Engineering Department [email protected], [email protected] Abstract. In this study, Dual Tone Multi Frequency (DTMF) signal generation and detection is implemented by using Goertzel Algorithm in MATLAB software. The DTMF signals are generated by using Cool Edit Pro Version 2.0 program for DTMF tone detection. The DTMF signal generation and detection algorithm are based on International Telecommunication Union (ITU) recommendations. Frequency deviation, twist, energy and time duration tests are performed on the DTMF signals. -

Rates for Interstate Inmate Calling Services, Report and Order on Remand and Fourth Further Notice of Proposed Rulemaking, WC Docket No

Before the Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. In the Matter of: ) Rates for Interstate Inmate Calling ) WC Docket No. 12-375 Services ) Comments of Helping Educate to Advance the Rights of Deaf Communities (HEARD) Telecommunications for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing, Inc. (TDI) National Association of the Deaf (NAD) Hearing Loss Association of America (HLAA) National Disability Rights Network (NDRN) Association of Late-Deafened Adults (ALDA) Cerebral Palsy and Deaf Organization (CPADO) Deaf Seniors of America (DSA) National Cued Speech Association (NCSA) Cuesign, Inc. American Deafness and Rehabilitation Association (ADARA) California Coalition of Agencies Serving the Deaf and Hard of Hearing (CCASDHH) Rehabilitation Engineering Research Center on Technology for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing, Gallaudet University (DHH-RERC) Rehabilitation Engineering Research Center on Universal Interface & Information Technology Access (IT-RERC) Samuelson-Glushko Technology Law & Policy Clinic (TLPC) • Colorado Law Counsel to TDI via electronic filing Brandon Ward, Caitlin League, and Michael November 23, 2020 Obregon, Student Attorneys Blake E. Reid Director [email protected] Helping Educate to Advance the Rights of Deaf Communities (HEARD) Talila A. Lewis, Co-Founder & Director • [email protected] Washington, DC https://www.behearddc.org Telecommunications for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing, Inc. (TDI) Eric Kaika, Chief Executive Officer • [email protected] Silver Spring, MD https://tdiforaccess.org National Association of the -

What to Do If You Hear Radio Communications on Your Telephone

What to do if you hear radio communications on your telephone Interference occurs when your telephone instrument fails to "block out" a nearby radio communication. Potential interference problems begin when the telephone is built at the factory. All telephones contain electronic components that are sensitive to radio frequencies, but cordless telephones are particularly susceptible because they use radio transmitters/receivers. Cordless telephones are also highly sensitive to electrical noise, (electric fences) radio interference, and the communications of other nearby cordless phones. Cordless phones with more features like messaging, redial and intercom, contain more electronic components; this creates a greater potential for outside interference. If the manufacturer does not build in interference protection, these components may react to nearby radio communications. For example, you could hear the transmission of a local radio station through your telephone’s handset. This is not necessarily a sign that the interference is intentional or that the interfering radio transmitter is illegal but that your equipment has no, or inadequate, protection. If you own an unprotected telephone, as the radio environment around you changes, you may sometimes hear unwanted radio communications. This is a technical problem, not a law enforcement problem Because interference problems begin at the factory, you should send your complaint to the manufacturer who built your telephone. It is important that you follow through and contact the manufacturer of your phone if you are having an interference problem. The company needs to know if you are unhappy about your phone’s failure to block out radio communications. Also, the manufacturer knows the designs of its telephones and may be able to suggest a solution for your specific phone. -

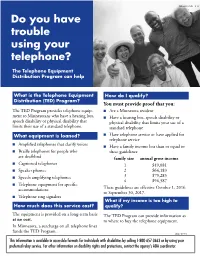

Telephone Equipment Distribution Program Can Help

DHS-4005-ENG 8-16 Do you have trouble using your telephone? The Telephone Equipment Distribution Program can help What is the Telephone Equipment How do I qualify? Distribution (TED) Program? You must provide proof that you: The TED Program provides telephone equip- Are a Minnesota resident ment to Minnesotans who have a hearing loss, Have a hearing loss, speech disability or speech disability or physical disability that physical disability that limits your use of a limits their use of a standard telephone. standard telephone What equipment is loaned? Have telephone service or have applied for telephone service Amplified telephones that clarify voices Have a family income less than or equal to Braille telephones for people who these guidelines: are deafblind family size annual gross income Captioned telephones 1 $49,081 Speaker phones 2 $64,183 Speech amplifying telephones 3 $79,285 4 $94,387 Telephone equipment for specific accommodations These guidelines are effective October 1, 2016 to September 30, 2017. Telephone ring signalers What if my income is too high to How much does this service cost? qualify? The equipment is provided on a long-term basis The TED Program can provide information as at no cost. to where to buy the telephone equipment. In Minnesota, a surcharge on all telephone lines funds the TED Program. ADA2 (12-12) This information is available in accessible formats for individuals with disabilities by calling 1-800-657-3663 or by using your preferred relay service. For other information on disability rights and protections, contact the agency’s ADA coordinator. How do I apply? Where are the regional offices? New applicants – Fill out and sign the application. -

Video Relay Service (VRS}

Links to VRS providers available at: www.puc.state.tx.us/relay Video Relay Service (VRS} Video Relay Service (VRS) enables deaf or hard-of-hearing persons who sign to communicate with voice telephone users (hearing persons) through video conference equipment (web cameras or video phone products). A voice telephone user can also initiate a VRS call by calling a VRS center, usually through a toll-free number. 1 VRS user goes to VRS website and gives the VI the other party's phone number. 2 The VI places the call and voices everything the VRS user signs to the other party. 4 The VI signs the spo ken reply to the VRS user. 3 Other party listens and then voices his/her reply. 8 Other Relay Features Spanish Speaking Users Spanish-speaking callers can directly connect to a Spanish speaking relay agent by dialing 1-800-662-4954. Relay Texas also provides Spanish translation relay agents. The service provides Spanish-to-Spanish as well as to Spanish-to-English translations. International Calls You may place and receive calls to and from anywhere in the world through Relay Texas. Callers originating from a country outside the U.S. can access Relay Texas by calling 1-605-224-1837. Blind or Visually Impaired Callers Dial1-877-826-9348 to use the reduced typing speed feature. During these calls the message will come across the users TTY or Braille TTY at the rate of 15 words per minute. The user can increase or decrease the rate in increments of 5 words per minute. -

The Dos and Don'ts of Videoconferencing in Higher

The Dos and Don’ts of Videoconferencing in Higher Education HUSAT Research Institute Loughborough University of Technology Lindsey Butters Anne Clarke Tim Hewson Sue Pomfrett Contents Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................1 Introduction .............................................................................................................................3 How to use this report ..............................................................................................................3 Chapter 1 Videoconferencing in Higher Education — How to get it right ...................................5 Structure of this chapter ...............................................................................................5 Part 1 — Subject sections ............................................................................................6 Uses of videoconferencing, videoconferencing systems, the environment, funding, management Part 2 — Where are you now? ......................................................................................17 Guidance to individual users or service providers Chapter 2 Videoconferencing Services — What is Available .....................................................30 Structure of this chapter ...............................................................................................30 Overview of currently available services .......................................................................30 Broadcasting -

Broadband for Development in the ESCWA Region Enhancing Access to ICT Services in a Global Knowledge Society

Broadband for Development in the ESCWA Region Enhancing Access to ICT Services in a Global Knowledge Society Broadband for Development in the ESCWA Region Enhancing Access to ICT Services in a Global Knowledge Society Acknowledgement and Disclaimer This publication was jointly funded by UN–ESCWA and Alcatel–Lucent, with additional support for final compilation and reproduction from the United Nations Development Account proj- ect “Capacity building for ICT policymaking”. The report was super- vised by Mansour Farah, Team Leader for ICT Policies, ESCWA, and Souheil Marine, Digital Bridge Manager, Alcatel–Lucent, who defined the initial project, jointly led the publication team, contributed to the drafting of various chapters, and assured the overall quali- ty of the publication. In preparing this publication, Ayman El–Sherbiny, First Informa- tion Technology Officer in ESCWA, contributed to the drafting of var- ious chapters and acted as a focal point, defining and coordinat- ing substantive assignments between national and regional consult- ants and the publication team. Imad Sabouni, ESCWA consultant, carried out the regional analysis of case studies, compiled various contributions, and drafted core chapters. Eric Delannoy, Alcatel–Lucent consultant, also contributed to the drafting of vari- ous chapters and provided technical input. Thanks are due to Mohamed Abdel–Wahab and Mohammed Al–Wahaibi, ESCWA consultants, for their valuable contributions of case studies on Egypt and Oman respectively, and also to Habib Torbey, CEO of Globalcom Data Services, for his input on Lebanon. We would like to express our sincere appreciation to Abdulilah Dewachi, Regional Adviser on ICT, ESCWA, and to Samir Aïta, ESCWA consultant, for their review and valuable comments lead- ing to enhancements to the final drafts of the publication.