US War Resister Migrations to Canada

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conscience and Peace Tax International

Conscience and Peace Tax International Internacional de Conciencia e Impuestos para la Paz NGO in Special Consultative Status with the Economic and Social Council of the UN International non-profit organization (Belgium 15.075/96) www.cpti.ws Bruineveld 11 • B-3010 Leuven • Belgium • Ph.: +32.16.254011 • e- : [email protected] Belgian account: 000-1709814-92 • IBAN: BE12 0001 7098 1492 • BIC: BPOTBEB1 UPR SUBMISSION CANADA FEBRUARY 2009 Executive summary: CPTI (Conscience and Peace Tax International) is concerned at the actual and threatened deportations from Canada to the United States of America of conscientious objectors to military service. 1. It is estimated that some 200 members of the armed forces of the United States of America who have developed a conscientious objection to military service are currently living in Canada, where they fled to avoid posting to active service in which they would be required to act contrary to their consciences. 2. The individual cases differ in their history or motivation. Some of those concerned had applied unsuccessfully for release on the grounds that they had developed a conscientious objection; many had been unaware of the possibility of making such an objection. Most of the cases are linked to the invasion of Iraq in 2003 and the subsequent military occupation of that country. Some objectors, including reservists mobilised for posting, refused deployment to Iraq on the grounds that this military action did not have lawful approval of the international community. Others developed their conscientious objections only after deployment to Iraq - in some cases these objections related to armed service in general on the basis of seeing what the results were in practice; in other cases the objections were specific to the operations in which they had been involved and concerned the belief that war crimes were being committed and that service in that campaign carried a real risk of being faced with orders to carry out which might amount to the commission of war crimes. -

Kriss Worthington

Kriss Worthington Councilmember, City of Berkeley, District 7 2180 Milvia Street, 5th Floor, Berkeley, CA 94704 PHONE 510-981-7170 FAX 510-981-7177 [email protected] CONSENT CALENDAR February 12, 2008 To: Honorable Mayor and Members of the City Council From: Councilmembers Kriss Worthington and Max Anderson Subject: Letter To Canadian Officials Requesting Sanctuary For U.S. War Resisters RECOMMENDATION: Send a letter to Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper, Minister of Citizenship and Immigration Diana Finley and Liberal Party leader Stephane Dion requesting that the government of Canada establish provisions to provide sanctuary for U.S. military service members who are living in Canada to resist fighting in the Iraq War. BACKGROUND: Throughout the Vietnam War era, Canada provided a place of refuge for United States citizens seeking to resist the war. Because of Canada’s rich tradition of being a refuge from militarism, approximately 200 U.S. military service people have moved to Canada to resist fighting in the Iraq War. However, it has become more difficult to immigrate to Canada and these war resisters are seeking refugee status in accord with United Nations guidelines. Unfortunately, their requests for refugee status have been rejected by the Canadian Refugee Board. Several resisters have appealed the Refugee Board decisions to the Supreme Court of Canada. While a court decision is pending these resisters are vulnerable to deportation back to the United States where they may face years of incarceration or even worst penalties. There is strong support among the Canadian people for the war resisters and the Canadian House of Commons is currently considering legislation to provide sanctuary to war resisters. -

Action Robin Long

Iraq War resister Robin Long jailed, facing three years in Army stockade Free Robin Long Now! Support GI resistance! Last month 25-year-old U.S. Army PFC Robin Long became the first war resister since the Vietnam War to be Action forcefully deported from Canadian soil and handed over to military authorities. What you can do now to support Robin Robin is currently being held in the El Paso County Jail, near Colorado Springs, Colorado, awaiting a military Donate to Robin’s Send letters of Send Robin a court martial for resisting the unjust 1 legal defense 2 support to Robin 3 money order for commissary items and illegal war against and occupation Online: Robin Long, CJC of Iraq. Robin will be court martialed couragetoresist.org/ 2739 East Las Vegas Anything Robin for desertion “with intent to remain robinlong Colorado Springs CO gets (postage, 80906 toothbrush, paper, By mail: away permanently”—Article 85 of the snacks, etc.) must be Make checks out to Robin’s pre-trial Uniform Code of Military Justice—in ordered through the “Courage to Resist / confinement has commissary. Each early September. The maximum IHC” and note “Robin been outsourced by inmate has an account allowable penalty for a guilty verdict on Long” in the memo Fort Carson military to which friends may field. Mail to: authorities to the local this charge is three years confinement, make deposits. To do Courage to Resist county jail. forfeiture of pay, and a dishonorable so, a money order in 484 Lake Park Ave #41 discharge from the Army. Oakland CA 94610 Robin is allowed to U.S. -

Letter to Canadian Officials Requesting Sanctuary for US War

Kriss Worthington Councilmember, City of Berkeley, District 7 2180 Milvia Street, 5th Floor, Berkeley, CA 94704 PHONE 510-981-7170 FAX 510-981-7177 [email protected] CONSENT CALENDAR February 12, 2008 To: Honorable Mayor and Members of the City Council From: Councilmembers Kriss Worthington and Max Anderson Subject: Letter To Canadian Officials Requesting Sanctuary For U.S. War Resisters RECOMMENDATION: Send a letter to Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper, Minister of Citizenship and Immigration Diana Finley and Liberal Party leader Stephane Dion requesting that the government of Canada establish provisions to provide sanctuary for U.S. military service members who are living in Canada to resist fighting in the Iraq War. BACKGROUND: Throughout the Vietnam War era, Canada provided a place of refuge for United States citizens seeking to resist the war. Because of Canada’s rich tradition of being a refuge from militarism, approximately 200 U.S. military service people have moved to Canada to resist fighting in the Iraq War. However, it has become more difficult to immigrate to Canada and these war resisters are seeking refugee status in accord with United Nations guidelines. Unfortunately, their requests for refugee status have been rejected by the Canadian Refugee Board. Several resisters have appealed the Refugee Board decisions to the Supreme Court of Canada. While a court decision is pending these resisters are vulnerable to deportation back to the United States where they may face years of incarceration or even worst penalties. There is strong support among the Canadian people for the war resisters and the Canadian House of Commons is currently considering legislation to provide sanctuary to war resisters. -

Court Martial of U.S. War Resister Confirms That Speaking out Against Iraq War Brings Harsher Punishment

WAR RESISTERS SUPPORT CAMPAIGN July 16, 2008/ 11:55 p.m. FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Att: News Editors Court Martial of U.S. War Resister confirms that speaking out against Iraq war brings harsher punishment TORONTO – Today’s harsh sentencing of U.S. War resister James Burmeister contradicts a recent Federal Court of Canada ruling that there was no evidence the U.S. military would inflict harsh punishment. On July 14, Federal Court Justice Anne Mactavish found there was no evidence that U.S. war conscientious objector Robin Long would be treated more harshly for having spoken out publicly against the war in Iraq. Mr. Long was deported from Canada on July 15. What happened to James Burmeister runs counter to Justice Mactavish’s assumptions in her ruling. Burmeister’s severe sentence indicates that soldiers who speak out publicly against the war and who have sought refuge in Canada are punished more severely by the U.S. military. At today’s Court Martial at Fort Knox, Kentucky, Burmeister received nine months in military prison and a Bad Conduct Discharge – the equivalent of a felony conviction. He was charged with being Absent Without Official Leave (AWOL). Evidence of Burmeister’s public statements against the use of “bait and kill” tactics in Iraq by the U.S. military – as well as documents showing his public association with the War Resisters Support Campaign in Canada – were submitted by the prosecution to bolster their case against him. Burmeister, an Iraq War veteran who sustained injuries from a roadside bomb attack was ordered to return to Iraq despite his injuries. -

CONSENT CALENDAR December 15, 2009 To: Honorable Mayor and Members of the City Council From: Peace and Justice Commission Submit

Peace and Justice Commission CONSENT CALENDAR December 15, 2009 To: Honorable Mayor and Members of the City Council From: Peace and Justice Commission Submitted by: Eric Brenman, Secretary, Peace and Justice Commission Subject: Universal and Unconditional Amnesty for Iraq, Afghanistan and Pakistan War Military Resisters and Veterans RECOMMENDATION At its meeting on November 2, 2009, the Peace and Justice Commission unanimously approved the following recommendation: Adopt a Resolution requiring the City of Berkeley to call for and support universal and unconditional amnesty for Iraq, Afghanistan and Pakistan war military resisters and veterans. M/S/C: (Meola, B./Lippman, G.) Ayes: Bohn, D.; Brody, D.; Kenin, W.; Lippman, G.; Litman, J.; Maran, R.; Marley, J.; Meola, B.; Nicely, M.; Sherman, M.; Sorgen, P. Noes: None. Abstain: None. Absent: Wornick, J. (excused) FISCAL IMPACTS OF RECOMMENDATION None. CURRENT SITUATION AND ITS EFFECTS Although accurate figures for the number of military personnel who have been classified as Absent Without Leave (“AWOL”), Unauthorized Absence (“UA”), or deserters since 9/11 are not available, the estimates range in the tens of thousands. While it would take a Freedom of Information Act Request to obtain AWOL statistics from the Pentagon, Universal and Unconditional Amnesty for Iraq, CONSENT CALENDAR Afghanistan and Pakistan War Military Resisters and Veterans December 15, 2009 counselors who speak with AWOL military personnel estimate that the percentage of AWOL personnel has more than doubled, from approximately .85% before 9/11 to 1.7 to 1.9% of the current 2.3 million military personnel (or forty-some thousand AWOLS). Due to an increase in the overall numbers of persons in the military, the number of AWOL persons has greatly increased in recent years. -

CONSENT CALENDAR January 19, 2010 To: Honorable Mayor And

Peace and Justice Commission CONSENT CALENDAR January 19, 2010 To: Honorable Mayor and Members of the City Council From: Peace and Justice Commission Submitted by: Eric Brenman, Secretary, Peace and Justice Commission Subject: Universal and Unconditional Amnesty for Iraq, Afghanistan and Pakistan War Military Resisters and Veterans RECOMMENDATION At its meeting on November 2, 2009, the Peace and Justice Commission unanimously approved the following recommendation: Adopt a Resolution requiring the City of Berkeley to call for and support universal and unconditional amnesty for Iraq, Afghanistan and Pakistan war military resisters and veterans. M/S/C: (Meola, B./Lippman, G.) Ayes: Bohn, D.; Brody, D.; Kenin, W.; Lippman, G.; Litman, J.; Maran, R.; Marley, J.; Meola, B.; Nicely, M.; Sherman, M.; Sorgen, P. Noes: None. Abstain: None. Absent: Wornick, J. (excused) FISCAL IMPACTS OF RECOMMENDATION None. CURRENT SITUATION AND ITS EFFECTS Although accurate figures for the number of military personnel who have been classified as Absent Without Leave (“AWOL”), Unauthorized Absence (“UA”), or deserters since 9/11 are not available, the estimates range in the tens of thousands. While it would take a Freedom of Information Act Request to obtain AWOL statistics from the Pentagon, Universal and Unconditional Amnesty for Iraq, CONSENT CALENDAR Afghanistan and Pakistan War Military Resisters and Veterans December 15, 2009 counselors who speak with AWOL military personnel estimate that the percentage of AWOL personnel has more than doubled, from approximately .85% before 9/11 to 1.7 to 1.9% of the current 2.3 million military personnel (or forty-some thousand AWOLS). Due to an increase in the overall numbers of persons in the military, the number of AWOL persons has greatly increased in recent years. -

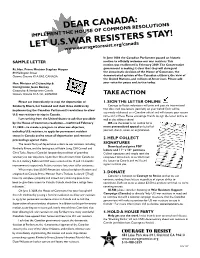

Dear Canada: Implement the House of Commons Resolutions

DEAR CANADA: IMPLEMENT THE HOUSE OF COMMONS RESOLUTIONS LET U.S.www.couragetoresist.org/canada WAR RESISTERS STAY! In June 2008 the Canadian Parliament passed an historic SAMPLE LETTER motion to offi cially welcome our war resisters. This motion was reaffi rmed in February 2009. The Conservative Rt. Hon. Prime Minister Stephen Harper government is making it clear that they will disregard 80 Wellington Street the democratic decision of the House of Commons, the Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0A2, CANADA demonstrated opinion of the Canadian citizenry, the view of the United Nations, and millions of Americans. Please add Hon. Minister of Citizenship & your voice for peace and justice today. Immigration Jason Kenney Citizenship & Immigration Canada Ottawa, Ontario K1A 1L1, CANADA TAKE ACTION Please act immediately to stop the deportation of 1. SIGN THE LETTER ONLINE Kimberly Rivera, her husband and their three children by Courage to Resist volunteers will print and post via international implementing the Canadian Parliament’s resolutions to allow fi rst class mail two letters (text left) on your behalf. Each will be separately addressed to a Canadian offi cial and will feature your return U.S. war resisters to stay in Canada. name and address. Please encourage friends to sign the letter online as I am writing from the United States to ask that you abide well at the address above! by the House of Commons resolution—reaffi rmed February OR use the letter as an outline for a 12, 2009—to create a program to allow war objectors, more personalized appeal on behalf of including U.S. -

Federal Court Rules in Favour of Iraq War Resister Dean Walcott Canadians Renew Call for Iraq War Resisters to Stay

War Resisters Support Campaign For Immediate Release April 7, 2011 Federal Court rules in favour of Iraq War resister Dean Walcott Canadians renew call for Iraq War resisters to stay TORONTO—On Tuesday, the Federal Court of Canada released a decision reaffirming there is evidence that U.S. Iraq War resisters are targeted for punishment because of their political beliefs if returned to the United States. The judgment <http://www3.sympatico.ca/ken.marciniec/20110405-FederalCourt- WalcottVMinCitizneshipImmigration_IMM-5527-08.pdf> in the judicial review of Iraq War resister and veteran Dean Walcott’s case also confirms that immigration officers must consider the war resisters’ sincerely held moral, political and religious beliefs. This is the ninth Federal Court or Federal Court of Appeal decision in favour of Iraq War resisters since 2008 and the seventh Federal Court decision to recognize that there is evidence that these war resisters are targeted for more severe punishment because they have expressed their objections to the Iraq War. In his decision, The Honourable Yves de Montigny concurred with the Federal Court of Appeal’s unanimous July 2010 decision that Iraq War resisters’ sincerely held beliefs must be assessed and cannot be ignored by immigration decision-makers. Justice de Montigny was critical of the immigration officer’s cookie-cutter reasons for denying Walcott’s Pre-Removal Risk Assessment (PRRA) application, calling them “disturbingly similar” to those that were provided in the case of the first female Iraq War resister, Kimberly Rivera. Each case is supposed to be decided on its own merits. The decision means that Walcott, a former U.S. -

2008 Fc 881 Between: James Corey Glass

Date: 20080717 Docket: IMM-2552-08 Citation: 2008 FC 881 BETWEEN: JAMES COREY GLASS 2008 FC 881 (CanLII) Applicant and THE MINISTER OF CITIZENSHIP AND IMMIGRATION Respondent REASONS FOR ORDER FRENETTE D.J. [1] This is a motion to stay the execution of an order rendered against the applicant for removal to the United States (U.S.), scheduled to be executed on July 10th, 2008. I granted the stay on July 9th, 2008 and here are my reasons. I. Background [2] The applicant is a citizen of the U.S. who came to Canada on August 6, 2006, claiming refugee status. His claim was dismissed on June 21, 2007; he was denied leave for judicial review of that decision. His Pre-Removal Risk Assessment (PRRA) was decided negatively on March 25, 2008. His humanitarian and compassionate (H&C) application was refused on the same day. Page: 2 [3] He now seeks judicial review of both decisions. The applicant’s claim results from his refusal to serve in the U.S. army in Iraq. He joined the Army National Guard (National Guard) in 2002 to serve his community in humanitarian missions in case of national disasters and local needs. He was told that the National Guard would never be involved in foreign wars. [4] In 1993, numerous National Guard units were advised they were activated to go to war in 2008 FC 881 (CanLII) Iraq and Afghanistan. After his transfer to the California National Guard, he was promoted to the rank of Sergeant. After activation, the National Guard unit of which Mr. -

Canadian Government's Single-Minded Determination to Deny

WAR RESISTERS SUPPORT CAMPAIGN Mon., July 14, 2008 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Canadian government’s single-minded determination to deny legitimacy of conscientious objection denounced Robin Long must leave Canada Toronto/CNW – Today’s Federal Court decision refusing to prevent the removal of conscientious objector Robin Long is a major disappointment for the majority of Canadians, 64% of whom support sanctuary for U.S. soldiers seeking refuge here. It is also at odds with the passage of June 3rd Parliamentary motion calling for the oppor- tunity for conscientious objectors to apply for permanent resident status, and an end to all deportations. “The federal government’s single-minded determination to deny the legitimacy of conscientious objection to what is plainly an illegal war rife with human rights abuses is abhorrent. Robin himself has been harassed by authorities by being arrested for violating a deportation order of which neither he nor his counsel were ever advised,” says Lee Zaslofsky. spokesperson for the War Resisters Support Campaign. “He’s been held in jail since July 4 and treated with disrespect by our government which seems intent on imposing American military law in Canada.” Canadian Immigration authorities – who report to Minister of Citizenship and Immigration Diane Finley – had kept secret a negative decision on Robin’s Pre-Removal Risk Assessment, making it impossible for his lawyer to file an appeal. “We have received hundreds of messages of support for Robin,” says Bob Ages of the Vancouver War Resisters Support Campaign. “We are calling on Canadians to take immediate action to tell the government that its attempts to overturn Canada’s longstanding tradition of sanctuary will be met with challenges everywhere.” The War Resisters Support Campaign pledges to redouble its efforts on behalf of all conscientious objectors. -

The Courage to Combat Humiliation

The Courage To Combat Humiliation By Pandora Hopkins Paper presented at the 2010 Workshop on Transforming Humiliation and Violent Conflict, Columbia University, New York, December 9-10, 2010 ABSTRACT: Despite, general perception, most U.S. citizens are not hawks. This lack of support for war is making U.S. leaders try to militarize public school students in the inner cities. Their military instructors are not likely to give them a well-rounded education or to inform them about the” total war” structure that has made civilians the main victims of warfare today. A small group of soldiers who have walked away from the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan have been trying to convey information from their personal experiences through publications and public appearances. They are the ones who have had to directly confront and overcome humiliation for disobeying, not only laws, but, what takes even more courage, time-honored beliefs about the necessity for warfare, i.e. its integral connection to heroism, patriotism, purification and obedience (the last often seen as a virtue in itself). The present paper is a proposal for our organization, Studies in Dignity and Humiliation, to study ways to support the war resistors’ efforts. I believe they may hold a key to unlocking the silence of the many Americans who are only like lemmings in one way: Both lemmings and U.S. citizens have been misunderstood. I Despite general perception, most U.S. citizens are not hawks The Lemmings Analogy: True—But Not What You Think Lemmings. Everyone knows that lemmings are tiny, furry creaturas biologically driven to committ suicide en masse.