Brand and Price Advertising in Online Markets"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Compaq Presario 1200XL.Pdf

Presario 1200XL Series Model XL300, XL300A, and XL300B Before You Product Specifications Begin Description Pin Battery Troubleshooting Assignments Operations Removal Parts MSG Index Sequence Catalog Welcome to the Maintenance & Service Guide (MSG) Welcome to the Maintenance and Service Guide (MSG) for Compaq Presario 1200XL Series Portable Notebooks. This online guide is designed to serve the needs of technicians whose job is to repair Compaq products. For copyright and trademark information, refer to the Notice section of this MSG. To locate your unit’s serial number, to see symbol conventions, or to view technician’s notes, see the Preface. This MSG is updated online as needed. For comments or questions about the contents of this MSG, contact Compaq. To report a technical problem, contact your Regional Support Center or IM Help Center. For help on navigating in this guide, refer to Using this Guide. Presario 1200XL Series Model XL300, XL300A, and XL300B Using this Guide To effectively use this guide, refer to the list of bookmarks at the left of the screen. These bookmarks help you navigate through the document quickly and easily. They are accessible from anywhere in the Maintenance and Service Guide (MSG). Viewing a Chapter Click one of the bookmarks or one of the color-coded bubbles on the Welcome page to view a chapter of this MSG. Expanding & Hiding Topics Click the + to expand or show the contents of a section, or click the – to hide the contents. Opening another Chapter Return to the Welcome page by clicking the bookmark, 1200 Series Maintenance and Service Guide, and then click the bookmark or color-coded bubble for another chapter. -

Compaq Presario 1200 Series Maintenance & Service Guide

Presario 1200 Series Models: XL101-XL113, XL115, XL118-XL127 Before You Product Specifications Begin Description Pin Battery Troubleshooting Assignments Operations Removal Parts MSG Index Sequence Catalog Welcome to the Maintenance & Service Guide (MSG) Welcome to the Maintenance and Service Guide (MSG) for Compaq Presario 1200XL Series Portable Notebooks. This online guide is designed to serve the needs of technicians whose job is to repair Compaq products. For copyright and trademark information, refer to the Notice section of this MSG. To locate your unit’s serial number, to see symbol conventions, or to view technician’s notes, see the Preface. This MSG is updated online as needed. For comments or questions about the contents of this MSG, contact Compaq. To report a technical problem, contact your Regional Support Center or IM Help Center. For help on navigating in this guide, refer to Using this Guide. Presario 1200 Series Models: XL101-XL113, XL115, XL118-XL127 Using this Guide To effectively use this guide, refer to the list of bookmarks at the left of the screen. These bookmarks help you navigate through the document quickly and easily. They are accessible from anywhere in the Maintenance and Service Guide (MSG). Viewing a Chapter Click one of the bookmarks or one of the color-coded bubbles on the Welcome page to view a chapter of this MSG. Expanding & Hiding Topics Click the + to expand or show the contents of a section, or click the – to hide the contents. Opening another Chapter Return to the Welcome page by clicking the bookmark, 1200 Series Maintenance and Service Guide, and then click the bookmark or color-coded bubble for another chapter. -

Compaq Maintenance & Service Guide

Presario 1200 Series Model XL2, XL201, XL202, XL203, XL204, XL205, XL212, XL220, XL222, XL223, XL3, XL301, XL302, XL303, XL304, XL305, XL307, XL310, XL311, XL312, XL314, XL320, XL323, XL325, XL326, XL327, XL330 Before You Product Begin Description Specifications Pin Battery & Power Assignments Management Troubleshooting Removal Parts Sequence Catalog MSG Index Welcome to the Maintenance & Service Guide (MSG) Welcome to the Maintenance and Service Guide (MSG) for Compaq Presario 1200XL Series Portable Notebooks. This online guide is designed to serve the needs of technicians whose job is to repair Compaq products. For copyright and trademark information, refer to the Notice section of this MSG. To locate your unit’s serial number, to see symbol conventions, or to view technician’s notes, see the Preface. This MSG is updated periodically online as needed. For comments or questions about the contents of this MSG, contact Compaq. To report a technical problem, contact your Regional Support Center or IM Help Center. For help on navigating in this guide, refer to Using this Guide. PRESARIO NOTEBOOK MAINTENANCE AND SERVICE GUIDE 1200 SERIES WELCOME TO THE MAINTENANCE & SERVICE GUIDE (MSG) 1 Presario 1200 Series Model XL2, XL201, XL202, XL203, XL204, XL205, XL212, XL220, XL222, XL223, XL3, XL301, XL302, XL303, XL304, XL305, XL307, XL310, XL311, XL312, XL314, XL320, XL323, XL325, XL326, XL327, XL330 Using this Guide To effectively use this guide, refer to the list of bookmarks at the left of the screen. These bookmarks help you navigate through the document quickly and easily. They are accessible from anywhere in the Maintenance and Service Guide (MSG). Viewing a Chapter Click one of the bookmarks or one of the color-coded bubbles on the Welcome page to view a chapter of this MSG. -

Annual Report 2008 CEO Letter

Annual Report 2008 CEO letter Dear Fellow Stockholders, Fiscal 2008 was a strong year with some notable HP gained share in key segments, while continuing accomplishments. We have prepared HP to perform to show discipline in our pricing and promotions. well and are building a company that can deliver Software, services, notebooks, blades and storage meaningful value to our customers and stockholders each posted doubledigit revenue growth, for the long term. Looking ahead, it is important to highlighting both our marketleading technology and separate 2008 from 2009, and acknowledge the improved execution. Technology Services showed difficult economic landscape. While we have made particular strength with doubledigit growth in much progress, there is still much work to do. revenue for the year and improved profitability. 2008—Solid Progress and Performance in a Tough The EDS Acquisition—Disciplined Execution of a Environment Multiyear Strategy With the acquisition of Electronic Data Systems In August, HP completed its acquisition of EDS, a Corporation (EDS), we continued implementing a global technology services, outsourcing and multiyear strategy to create the world’s leading consulting leader, for a purchase price of $13 technology company. Additionally, we made solid billion. The EDS integration is at or ahead of the progress on a number of core initiatives, including operational plans we announced in September, and the substantial completion of phase one of HP’s customer response to the acquisition remains very information technology transformation. positive. Fiscal 2008 was also a difficult year, during which The addition of EDS further expands HP’s economic conditions deteriorated. -

Sin Ko Electronics Industrial Group Co., Limited

Sin Ko Electronics Industrial Group Co., Limited OFFICE ADDRESS:ROOM 031,4 FLOORS,ELECTRONIC WORLD,NEW HUAQIANG SQUARE,SHENZHEN,GUANGDONG,CHINA Contact Way:Name:Sophie Li Email:[email protected] MSN:[email protected] Skype:sinko009 FACTORY ADDRESS:5TH FLOOR,C BUILDING,INDUSTRIAL PARK,DONGLANG,FANGCUN,GUANGZHOU,GUANGDONG,CHINA Website:http://shenkeweiye.en.made-in-china.com/ Miss Sophie:+86-13266544269 LAPTOP BATTERY CATALOG Item Model Specification Part No Replacement for MOQ is 10pcs/model,If less than 10pcs/model,price should be $17.5per pcs IBM Cell Type: Li-ion 02K6919, 02K7016, Voltage: 11.1V 02K7018, 10L2158, IBM ThinkPad 600, 600A, 600D, Capacity: 4400mAh 10L2159, 12J2464, ASM 600E, 600X Series; SKB1 Weight: 340.3g 12P4065, FRU 02K6506, IBM ThinkPad 600X(2645-5EU). 130.60x72.30x25.50mm FRU 02K6528, FRU 02K6904, FRU 12P4064 600(6cell) Color: Black Cell Type: Li-ion Voltage: 14.4V Capacity: 1900mAh 93P0998, 92P0999, SKB2 92P1009, IBM ThinkPad X40,X41 Series Weight: 175.7g 92P1000 208.35 x 46.75 x 15.00 mm X40(4cell) Color: Black Cell Type: Li-ion Voltage: 14.4V Capacity: 4300mAh 92P0998, 92P0999, SKB3 Weight: 385.2g 92P1009, 92P1009, IBM ThinkPad X40,X41 Series 第 1 页,共 59 页 92P1078 X40(H)(8cell) 92P0998, 92P0999, SKB3 92P1009, 92P1009, IBM ThinkPad X40,X41 Series 92P1078 Color: Black X40(H)(8cell) Cell Type: Li-ion Voltage: 10.8V 02K6651, 02K6652, 02K6678, 02K6712, Capacity: 4400mAh IBM ThinkPad X20, X21, X22, SKB4 02K6837, 02K6838, X23, X24 Series; Weight: 322g 02K6839, 02K6850, 208.60*53.20*20.50 mm 08K8024 X20(6cell) -

Jason, Topex Now Work in Tandem

Inside August 1, 2003 Volume 33 Number 15 News Briefs . 2 Surviving the Amazon . 3 Special Events Calendar . 2 Passings . 4 100s of Galaxies For Galex . 3 Classifieds . 4 Jet Propulsion Laboratory he Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment impact on atmospheric weather patterns, fisheries and global climate change.” T (Grace) mission has released its first scence Grace is accomplishing that goal by providing a more precise defini- product, the most accurate map yet of Earth’s gravity field. Grace, tion of Earth’s geoid, an imaginary surface defined only by Earth’s gravity field, upon which Earth’s ocean surfaces would lie if not dis- which is managed by JPL, is the newest tool for scientists working turbed by other forces such as ocean currents, winds and tides. The to unlock secrets of ocean circulation and its effects on climate. geoid height varies around the world by up to 200 meters (650 feet). “I like to think of the geoid as science’s equivalent of a carpenter’s Created from 111 days of selected Grace data to help calibrate and level. It tells us where horizontal is,” Tapley said. “Grace will tell us the Grace quickly validate the mission’s instruments, this preliminary model improves geoid with centimeter-level precision.” knowledge of the gravity field so much it is being released to oceanogra- So why is knowing the geoid height so important? Dr. Lee-Lueng Fu, phers now, months in advance of the scheduled start of routine Grace produces Topex/Poseidon and Jason project scientist at JPL, said, “The ocean’s science operations. -

Копия Hi-Capacity Rozn

ООО «МАК ХАУС» Факт. адр.: 04112, Киев ЕГРПОУ 19358827, т/с 2600915237 ул. Дегтяревская, 48, оф. 109 в ОАО «Райффайзен Банк Аваль» тел. (044) 490-9928 МФО 300335, ИНН: 193588226104 факс (044) 494-3820 № св. НДС: 37548031 www.machouse.ua Юр. адр.: 01042, Киев, ул. И. Кудри, 37-а, оф. 69 Прайс-лист HI CAPACITY 14.01.2009 Партномер Описание Комм. Цена, Грн. BTH0002A Battery Tester AA/AAA/9V CR-V3 2CR5 120 CAA0625A AC Adapter 15-17v IBM Various Thinkpads 620 CAA0626A AC Adapter 15-17v output Compaq LTE 5000 620 CAA0627A AC Adapter 15-17v Toshiba 15-17v 72W 620 CAA0627B AC adapter 15-17v Toshiba P4 Models 710 CAA0629A AC Adapter 15-17v Sony Vaio 16v models 620 CAA0630A AC Adapter 15-17V Dell LM DEC HiNote VP500 620 CAA0631A AC adapter 18-20v Multi Manufacturer 620 CAA0631B AC Adapter 18-20v 90W Toshiba Satellite 1900 710 CAA0631C AC Adapter 120W 18-20v 6A Toshiba Satellite P25 A60 *** 980 CAA0632B Ac Adapter 18-20v 90W Gateway Solo 5300 800 CAA0633A AC Adapter 18-20V output Multi-fit Adaptor 620 CAA0633B AC Adapter 18-20V 90W Sharp Actius GP20W 710 CAA0633C 120W Ac Adapter Toshiba Satellite P10 980 CAA0634A AC Adapter 18-20v Sony Vaio 19v models 620 CAA0634B AC Adapter 18-20v 90W Sony Vaio PCG-GRZ series 710 CAA0634C AC Adapter 19v 6.2A 120W Sony Vaio PCG-FRV GRT100 980 CAA0634D AC Adapter 150W Sony Vaio PCG-GRT280ZG 950 CAA0636A AC Adapter 18-20v Dell Latitude CPi series 620 CAA0638A AC Adapter 21-24v Apple Powerbook 190 5300 series 620 CAA0639A AC Adapter 21-24v output Apple PowerBooks various 620 CAA0645A AC adapter / External power supply -

Validated Products List: Programming Languages, Database Language

NISTIR 469 (Supersedes NISTIR 4623) VALIDATED PRODUCTS LIST 1991 No. 4 Programming Languages Database Language SQL Graphics ®OSIP Judy B. Kailey POSIX Editor U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE National Institute of Standards and Technology Computer Systems Laboratory Software Standards Validation Group Gaithersburg, MD 20899 October 1991 (Supersedes July 1991 issue) U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE Robert A. Mosbacher, Secretary NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF STANDARDS AND TECHNOLOGY John W. Lyons, Director — QC 100 .U56 NIST //4690 1991 V C.2 NISTIR 4690 (Supersedes NISTIR 4623) - ' J JF VALIDATED PRODUCTS LIST 1991 No. 4 Programming Languages Database Langucige SQL Graphics GOSIP Judy B. Kailey POSIX Editor U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE National Institute of Standards and Technology Computer Systems Laboratory Software Standards Validation Group Gaithersburg, MD 20899 October 1991 (Supersedes July 1991 issue) U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE Robert A. Mosbacher, Secretary NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF STANDARDS AND TECHNOLOGY John W. Lyons, Director FOREWORD The Validated Products List (formerly called the Validated Processor List) is a collection of registers describing implementations of Federal Information Processing Standards (FIPS) that have been tested for conformance to FIPS. The Validated Products List also contains information about the organizations, test methods and procedures that support the validation programs for the FIPS identified in this document. The Validated Products List is updated quarterly. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 1-1 1.1 Purpose 1-1 1.2 Document Organization 1-1 1.2.1 Programming Languages 1-1 1.2.2 Database Language SQL 1-2 1.2.3 Graphics 1-2 1.2.4 GOSIP 1-2 1.2.5 POSIX 1-2 1.2.6 FIPS Conformance Testing Products 1-2 2. -

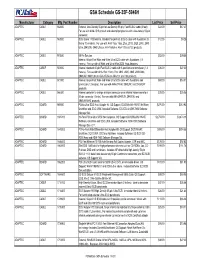

GSA Schedule for Website 1-09-03.XLS

GSA Schedule GS-35F-5946H Manufacturer Category Mfg. Part Number Description List Price Sell-Price ADAPTEC CABLE 562800 External, Low-Density 50-pin to Low-Density 50-pin, Fast SCSI-2 cable (3 feet). $22.00 $17.47 For use with AHA-1510 product and external peripherals with a low-density 50-pin connector. ADAPTEC CABLE 563000 SCSI Cable 1100 Internal, standard 50-pin Fast SCSI-2 cable with 5 positions (5 $12.00 $9.28 feet or 1.5 meters). For use with AHA-15xx, 16xx, 27xx, 2910, 2920, 2940, 2940 Ultra, 2940UW, 3940 Ultra or AVA-1505A or AAA-131 and 133 products. ADAPTEC CABLE 915800 68 Pin Solution $52.00 $39.86 Internal, 68-pin Fast Wide and Wide Ultra SCSI cable with 5 positions (1.1 meters). For use with all Wide and Ultra Wide SCSI Host Adapters. ADAPTEC CABLE 973000 Internal, standard 50-pin Fast SCSI-2 cable with 5 positions and terminator (1.3 $35.00 $27.30 meters). For use with AHA-15xx, 16xx, 27xx, 2910, 2920, 2940, 2940 Ultra, 2940UW, 3940 Ultra or AVA-1505A or AAA-131 and 133 products. ADAPTEC CABLE 973100 Internal, 68-pin Fast Wide and Wide Ultra SCSI cable with 5 positions and $69.00 $53.51 terminator (1.3 meters). For use with AHA-274xW, 2940UW, and 3940AUW products. ADAPTEC CABLE 986300 Internal converter to change a 68-pin connector on an internal ribbon cable to a $30.00 $25.06 50-pin connector (1 inch). For use with AHA-2940UW, 3940UW, and 3940UW/MAC products. -

Of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 (Amendment No

SCHEDULE 14A INFORMATION Proxy Statement Pursuant to Section 14(a) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 (Amendment No. ) Filed by the Registrant /X/ Filed by a party other than the Registrant / / Check the appropriate box: / / Preliminary Proxy Statement / / CONFIDENTIAL, FOR USE OF THE COMMISSION ONLY (AS PERMITTED BY RULE 14a-6(e)(2)) / / Definitive Proxy Statement /X/ Definitive Additional Materials / / Soliciting Material Pursuant to Section 240.14a-12 COMPUTER ASSOCIATES INTERNATIONAL, INC. - -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- (Name of Registrant as Specified In Its Charter) - -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- (Name of Person(s) Filing Proxy Statement, if other than the Registrant) Payment of Filing Fee (Check the appropriate box): /X/ No fee required. / / Fee computed on table below per Exchange Act Rules 14a-6(i)(4) and 0-11. (1) Title of each class of securities to which transaction applies: ------------------------------------------------------------------------ (2) Aggregate number of securities to which transaction applies: ------------------------------------------------------------------------ (3) Per unit price or other underlying value of transaction computed pursuant to Exchange Act Rule 0-11 (set forth the amount on which the filing fee is calculated and state how it was determined): ------------------------------------------------------------------------ (4) Proposed maximum aggregate value of transaction: ------------------------------------------------------------------------ -

HP 2002 Annual Re P O Rt I T 'S Working

HP 2002 annual re p o rt I t ’s working. It may be what people are saying about H P ’s integration eff o rt s , but more import a n t l y, it’s what p e o p l e s a y when technology s o l v e s a s e e m i n g l y impossible pro b l e m for the first time, or reliably p e rf o rms a transaction for the millionth. I t ’s working. When technology propels a company into new markets. Cuts millions in cost out of a business. Tracks a customer ord e r. Powers the stock market. When it models aberrant weather p a t t e rns, or serious diseases, or economic turbulence — and in the process, makes possible new policies, treatments, cures. When technology opens up new opportunities in underserv e d communities. Helps car engineers cheat the wind. Or makes a parent smile. It is for these moments that we are building HP into the world’s most capable technology company. A company dedicated to harnessing technology — in all its complexity, power and hope — not just to make a p rofit, but to make a diff e re n c e . Our re l a t i o n s h i p s Rightfully so, customers are demanding more than ever from their technology part n e r s . financial markets + HP: HP people and technology power14 of the world’s largest stock exchanges. Hong Kong + HP: HP technology enables citizens in Hong Kong to access government services from public kiosks. -

A List of Our Laptop Replacement Batteries We Sell: NO. FY P/N Fit

A List of Our Laptop Replacement Batteries We Sell: NO. FY P/N Fit For Models Voltage Capacit Picture (V) y (mAh) HP & Compaq COMPAQ FYCQ1700 for COMPAQ EVO 14.4 4400 N160,N800,N1000 Series / Presario 900 Series / Presario 1500 Series / Presario 1700,17XL Series / Presario 2800 Series COMPAQ FYCQ1701 for COMPAQ EVO 10.8 4400 N160,N800,N1000 Series / Presario 900 Series / Presario 1500 Series / Presario 1700,17XL Series / Presario 2800 Series COMPAQ FYCQ1600 for COMPAQ Presario 1200, 14.4 4400 1200XL 12XL, 14XL, 1600, 1600XL, 1800, 1800XL, 18XL COMPAQ FYCQP700 Compaq EVO N105 Series, 14.8 4400 Compaq EVO N115 Series, Compaq Presario 700 Series, Presario 705, Presario 710, Presario 711CL, Presario 715/720US/721CL/722US/ 723RSH/725/725US/730US/ 732US COMPAQ FYCQZV50 Pavilion ZD8000, ZV5000, 14.8 4400 00 ZV5200, ZV6000, ZX5000, Compaq PP2100, 2200, 2210, Presario R3000, R4000 Series, NX9110, 9600 Series COMPAQ FYCQZV50 Pavilion ZD8000, ZV5000, 14.8 6600 00H ZV5200, ZV6000, ZX5000, Compaq PP2100, 2200, 2210, Presario R3000, R4000 Series, NX9110, 9600 Series COMPAQ FYCQ1900 Presario B1900, B1916TU 14.4 2400 Series COMPAQ FYCQ1900 Presario B1900, B1916TU 14.4 4400 H Series COMPAQ FYCQTC10 Tablet PC TC1000, 11.1 3600 00 TC1100 Series PB2150 COMPAQ FYCQN600 COMPAQ Evo N600, N600c, 14.8 4400 N610c, N610v, N620c series HP FYHPTX10 Replacement for HP Pavilion 7.4 4400 00 tx1000, tx1100, tx1200, tx1300, tx1400, tx2000, tx2100, tx2500 Series HP FYHPTX10 Replacement for HP Pavilion 7.4 8800 00H tx1000, tx1100, tx1200, tx1300, tx1400, tx2000, tx2100,