Migration, Home Range and Important Use Areas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wilderness on the Edge: a History of Everglades National Park

Wilderness on the Edge: A History of Everglades National Park Robert W Blythe Chicago, Illinois 2017 Prepared under the National Park Service/Organization of American Historians cooperative agreement Table of Contents List of Figures iii Preface xi Acknowledgements xiii Abbreviations and Acronyms Used in Footnotes xv Chapter 1: The Everglades to the 1920s 1 Chapter 2: Early Conservation Efforts in the Everglades 40 Chapter 3: The Movement for a National Park in the Everglades 62 Chapter 4: The Long and Winding Road to Park Establishment 92 Chapter 5: First a Wildlife Refuge, Then a National Park 131 Chapter 6: Land Acquisition 150 Chapter 7: Developing the Park 176 Chapter 8: The Water Needs of a Wetland Park: From Establishment (1947) to Congress’s Water Guarantee (1970) 213 Chapter 9: Water Issues, 1970 to 1992: The Rise of Environmentalism and the Path to the Restudy of the C&SF Project 237 Chapter 10: Wilderness Values and Wilderness Designations 270 Chapter 11: Park Science 288 Chapter 12: Wildlife, Native Plants, and Endangered Species 309 Chapter 13: Marine Fisheries, Fisheries Management, and Florida Bay 353 Chapter 14: Control of Invasive Species and Native Pests 373 Chapter 15: Wildland Fire 398 Chapter 16: Hurricanes and Storms 416 Chapter 17: Archeological and Historic Resources 430 Chapter 18: Museum Collection and Library 449 Chapter 19: Relationships with Cultural Communities 466 Chapter 20: Interpretive and Educational Programs 492 Chapter 21: Resource and Visitor Protection 526 Chapter 22: Relationships with the Military -

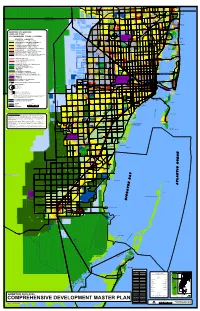

Comprehensive Development Master Plan (CDMP) and Are NAPPER CREEK EXT Delineated in the Adopted Text

E E E A I E E E E E V 1 E V X D 5 V V V V I I V A Y V A 9 A S A A A D E R A 7 I A W 7 2 U 7 7 2 K 7 O 3 7 H W 7 4 5 6 P E W L 7 E 9 W T W N F V W E V 7 W N W N W A W N V 2 A N N 5 N N 7 A 7 S 7 0 1 7 I U 1 1 8 W S DAIRY RD GOLDEN BEACH W SNAKE CREEK CANAL IVE W N N N NW 202 ST AVENTURA BROWARD COUNTY MAN C LEH SWY OMPIAA-MLOI- C K A MIAMI-DADE COUNTY DAWDEES T CAOIRUPNOTYR T NW 186 ST MIAMI GARDENS SUNNY ISLES BEACH E K P T ST W A NE 167 NORTH MIAMI BEACH D NW 170 ST O I NE 163 ST K R SR 826 EXT E E E O OLETA RIVER E V C L V STATE PARK A A H F 0 O 2 1 B 1 ADOPTED 2015 AND 2025 E E E T E N R X N D E LAND USE PLAN * NW 154 ST 9 R Y FIU/BUENA MIAMI LAKES S W VISTA H 1 FOR MIAMI-DADE COUNTY, FLORIDA OPA-LOCKA E AIRPORT I S HAULOVER X U I PARK D RESIDENTIAL COMMUNITIES NW 138 ST OPA-LOCKA W ESTATE DENSITY (EDR) 1-2.5 DU/AC G ESTATE DENSITY W/ ONE DENSITY INCREASE (DI-1) R NORTH MIAMI BAL HARBOUR A T BR LOW DENSITY (LDR) 2.5-6 DU/AC IG OAD N BAY HARBOR ISLANDS HIALEAH GARDENS Y CSW LOW DENSITY W/ ONE DENSITY INCREASE (DI-1) Y AMELIA EARHART PKY E PARK E V E E BISCAYNE PARK E V LOW-MEDIUM DENSITY (LMDR) 6-13 DU/AC V A V V V A D I A A A SURFSIDE MDOC A V 7 M LOW-MEDIUM DENSITY W/ ONE DENSITY INCREASE (DI-1) 2 L 2 7 NORTH 2 1 A B INDIAN CREEK VILLAGE I 2 E E W W E E M W V MEDIUM DENSITY (MDR) 13-25 DU/AC N N N W N V N A N Y NW 106 ST N A 6 MEDIUM DENSITY W/ ONE DENSITY INCREASE (DI-1) A HIALEAH C S E IS N MEDIUM-HIGH DENSITY (MHDR) 25-60 DU/AC N B I MEDLEY L L HIGH DENSITY (HDR) 60-125 DU/AC OR MORE/GROSS AC E MIAMI SHORES O V E C A TWO DENSITY -

11 August 2006 J. Michael Meyers USGS Patuxent Wildlife

11 August 2006 J. Michael Meyers USGS Patuxent Wildlife Research Center Warnell School of Forestry and Natural Resources The University of Georgia Athens, GA 30602-2152 706-542-1882; email [email protected] RH: Florida bald eagle migration • Mojica and Meyers MIGRATION, HOME RANGE, AND IMPORTANT USE AREAS OF FLORIDA SUB-ADULT BALD EAGLES ELIZABETH K. MOJICA, Warnell School of Forestry and Natural Resources, University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602, USA J. MICHAEL MEYERS, USGS Patuxent Wildlife Research Center, Warnell School of Forestry and Natural Resources, University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602, USA Final Performance Report 9 September 2005 – 1 June 2006 Keywords: Bald eagle, Haliaeetus leucocephalus, migration, stopover, home range, roost, nearest neighbor. Mojica and Meyers 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT....................................................................................................3 INTRODUCTION ...........................................................................................4 OBJECTIVES: ...............................................................................................5 METHODS.....................................................................................................6 Important use areas ...................................................................................6 Migratory eagle seasonal home ranges .....................................................7 Non-migratory eagle home ranges.............................................................8 Migration ....................................................................................................9 -

2001 SWFWMD Land Acquisition Plan

Five-Year Land Acquisition Plan 2001 SWFWMD i Land Acquisition Five-Year Plan 2001 Southwest Florida Water Management District Five-Year Land Acquisition Plan 2001 If a disabled individual wishes to obtain the information contained in this document in another form, please contact Cheryl Hill at 1-800-423-1476, extension 4452; TDD ONLY 1-800-231-6103; FAX (352)754-68771 ii Table of Contents Table of Contents Introduction and History 111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111 1 Save Our Rivers 111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111 1 Preservation 2000 11111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111 1 Florida Forever 1111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111 3 Selection and Evaluation Process 11111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111 5 Less-Than-Fee Acquisitions 111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111 10 Partnerships 11111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111 13 Surplus Lands111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111 16 Land Use/Management Activities111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111 17 Management Planning 11111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111 17 Land Use Implementation 111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111 -

Brooker Creek Preserve Management Plan

BROOKER CREEK PRESERVE MANAGEMENT PLAN prepared for PINELLAS COUNTY DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT prepared by Institute for Enviionmental Studies at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH FLORIDA in association with HDR Engineering, Inc. Breuggemann & Associates Laurie Macdonald, M. S, Zoologist Florida Audubon Society James Layne, PLD. EHI, Inc. December 1,1993 TABLE OF CONTENTS ListofFigures .................................................... iii ListofTables ...................................................... iv Acknowledgements ................................................... v ListofContributors ................................................. vi Summary Description, Proposed Facilities, and Recommendations .............. vii I. INTRODUCLTON Location of the Preserve ....................................... 1 Goals and Mission of the Preserve ............................... 1 11. PHYSICAL DESCRIPTION OF THE PRESERVE Drainage .................................................. 1 -WaterQuality............................................ 3 Topography ................................................ 3 Geology and soils ............................................ 3 Man-made features .......................................... 7 BIOLOGICAL DESCRIPTION OF THE PRESERVE A. Habitat Types Provided on the Preserve ........................... 8 Historical communities ....................................... 8 Existing communities -Land uselland cover ..................................... 10 -Natural plant communities ............................... -

NENHC 2008 Abstracts

Abstracts APRIL 17 – APRIL 18, 2008 A FORUM FOR CURRENT RESEARCH The Northeastern Naturalist The New York State Museum is a program of The University of the State of New York/The State Education Department APRIL 17 – APRIL 18, 2008 A FORUM FOR CURRENT RESEARCH SUGGESTED FORMAT FOR CITING ABSTRACTS: Abstracts Northeast Natural History Conference X. N.Y. State Mus. Circ. 71: page number(s). 2008. ISBN: 1-55557-246-4 The University of the State of New York THE STATE EDUCATION DEPARTMENT ALBANY, NY 12230 THE UNIVERSITY OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK Regents of The University ROBERT M. BENNETT, Chancellor, B.A., M.S. ................................................................. Tonawanda MERRYL H. TISCH, Vice Chancellor, B.A., M.A., Ed.D. ................................................. New York SAUL B. COHEN, B.A., M.A., Ph.D.................................................................................. New Rochelle JAMES C. DAWSON, A.A., B.A., M.S., Ph.D. .................................................................. Peru ANTHONY S. BOTTAR, B.A., J.D. ..................................................................................... Syracuse GERALDINE D. CHAPEY, B.A., M.A., Ed.D. ................................................................... Belle Harbor ARNOLD B. GARDNER, B.A., LL.B. .................................................................................. Buffalo HARRY PHILLIPS, 3rd, B.A., M.S.F.S. ............................................................................. Hartsdale JOSEPH E. BOWMAN, JR., B.A., -

Florida Communities Trust Annual Report 2016-2017

Florida Communities Trust Annual Report Fiscal Year 2016-2017 Office of Operations Land and Recreation Grants Section Florida Department of Environmental Protection September 30, 2017 3900 Commonwealth Boulevard, MS 103 Tallahassee, Florida 32399-3000 www.dep.state.fl.us Florida Communities Trust Annual Report Fiscal Year 2016-2017 1 Table of Contents LETTER FROM THE CHAIR ....................................................................................................... 1 PROJECT LOCATION MAP ........................................................................................................ 2 FLORIDA COMMUNITIES TRUST .............................................................................................. 3 MISSION AND ACCOMPLISHMENTS ......................................................................................... 4 PARK HAPPENINGS FOR FISCAL YEAR 2016-2017 ................................................................ 8 ACQUIRED PROJECTS BY COUNTY 1991-2017 .................................................................... 12 SUMMARY OF FINANCIAL ACTIVITIES ................................................................................... 29 FLORIDA COMMUNITIES TRUST BOARD MEMBERS ............................................................ 31 Front Cover Photo: Victory Pointe Park (f.k.a. West Lake Park) Unique Abilities 2017 Cycle FCT # 16-005-UA17, City of Clermont, FL Back Cover Photo: Myers-Stickel Property Unique Abilities 2017 Cycle FCT # 16-012-UA17, St. Lucie County, FL Florida Communities Trust -

Trademarks of Privilege: Naming Rights and the Physical Public Domain

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository University of New Hampshire – Franklin Pierce Law Faculty Scholarship School of Law 1-1-2007 Trademarks of Privilege: Naming Rights and the Physical Public Domain Ann Bartow University of New Hampshire School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/law_facpub Part of the Intellectual Property Law Commons, and the Law and Society Commons Recommended Citation Ann Bartow, "Trademarks of Privilege: Naming Rights and the Physical Public Domain," 40 U.C. DAVIS L. REV. 919 (2007). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of New Hampshire – Franklin Pierce School of Law at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Law Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Trademarks of Privilege: Naming Rights and the Physical Public Domain Ann Bartow* This Article critiques the branding and labeling of the physical public domain with the names of corporations, commercial products, and individuals. It suggests that under-recognized public policy conflicts exist between the naming policies and practices of political subdivisions, trademark law, and right of publicity doctrines. It further argues that naming acts are often undemocratic and unfair, illegitimately appropriate public assets for private use, and constitute a limited form of compelled speech. It concludes by considering alternative mechanisms by which the names of public facilities could be chosen. TABLE OF CONTENTS IN TRO DU CTIO N .................................................................................. -

Chapter 1: the Everglades to the 1920S Introduction

Chapter 1: The Everglades to the 1920s Introduction The Everglades is a vast wetland, 40 to 50 miles wide and 100 miles long. Prior to the twentieth century, the Everglades occupied most of the Florida peninsula south of Lake Okeechobee.1 Originally about 4,000 square miles in extent, the Everglades included extensive sawgrass marshes dotted with tree islands, wet prairies, sloughs, ponds, rivers, and creeks. Since the 1880s, the Everglades has been drained by canals, compartmentalized behind levees, and partially transformed by agricultural and urban development. Although water depths and flows have been dramatically altered and its spatial extent reduced, the Everglades today remains the only subtropical ecosystem in the United States and one of the most extensive wetland systems in the world. Everglades National Park embraces about one-fourth of the original Everglades plus some ecologically distinct adjacent areas. These adjacent areas include slightly elevated uplands, coastal mangrove forests, and bays, notably Florida Bay. Everglades National Park has been recognized as a World Heritage Site, an International Biosphere Re- serve, and a Wetland of International Importance. In this work, the term Everglades or Everglades Basin will be reserved for the wetland ecosystem (past and present) run- ning between the slightly higher ground to the east and west. The term South Florida will be used for the broader area running from the Kississimee River Valley to the toe of the peninsula.2 Early in the twentieth century, a magazine article noted of the Everglades that “the region is not exactly land, and it is not exactly water.”3 The presence of water covering the land to varying depths through all or a major portion of the year is the defining feature of the Everglades. -

Turkey Point Units 6 & 7 COLA

Turkey Point Units 6 & 7 COL Application Part 2 — FSAR SUBSECTION 2.4.1: HYDROLOGIC DESCRIPTION TABLE OF CONTENTS 2.4 HYDROLOGIC ENGINEERING ..................................................................2.4.1-1 2.4.1 HYDROLOGIC DESCRIPTION ............................................................2.4.1-1 2.4.1.1 Site and Facilities .....................................................................2.4.1-1 2.4.1.2 Hydrosphere .............................................................................2.4.1-3 2.4.1.3 References .............................................................................2.4.1-12 2.4.1-i Revision 6 Turkey Point Units 6 & 7 COL Application Part 2 — FSAR SUBSECTION 2.4.1 LIST OF TABLES Number Title 2.4.1-201 East Miami-Dade County Drainage Subbasin Areas and Outfall Structures 2.4.1-202 Summary of Data Records for Gage Stations at S-197, S-20, S-21A, and S-21 Flow Control Structures 2.4.1-203 Monthly Mean Flows at the Canal C-111 Structure S-197 2.4.1-204 Monthly Mean Water Level at the Canal C-111 Structure S-197 (Headwater) 2.4.1-205 Monthly Mean Flows in the Canal L-31E at Structure S-20 2.4.1-206 Monthly Mean Water Levels in the Canal L-31E at Structure S-20 (Headwaters) 2.4.1-207 Monthly Mean Flows in the Princeton Canal at Structure S-21A 2.4.1-208 Monthly Mean Water Levels in the Princeton Canal at Structure S-21A (Headwaters) 2.4.1-209 Monthly Mean Flows in the Black Creek Canal at Structure S-21 2.4.1-210 Monthly Mean Water Levels in the Black Creek Canal at Structure S-21 2.4.1-211 NOAA -

Savannah Watershed Water Quality Assessment 2003

Tugaloo/Seneca River Basin Watershed Unit Index Map 8 - Digit Hydrologic Unit 11 - Digit Hydrologic Unit 010 030 N 060 050 03060101 010 120 070 090 060 040 03060102 100 080 040 130 5 0 5 10 15 Miles r e v i à ala $ ah R Nant est k For ional SV-308 C Nat d a a g B o o Chattooga River Watershed à t t SV-792 a # Ch ork (03060102-010) East F SC0000451 er v K i ing k R C Sumter National Forest L ic I à k "!1 0 7 $ r L a o g C B SV-227 k ga r too at Ch !"2 8 W h et sto ne r r B e v i R Sumter National $ Water Quality Monitoring Sites Forest à ll Biological Monitoring Sites Fa à $ k # NPDES Permits SV-199 C Highways Streams k C (/7 6 County Lines Long Lakes SCDHEC 11-Digit Hydrologic Units Public Lands a g o O o po tt ssu a m h C C k e k a L o o l a g u $ T SV-359 N 2 0 2 Miles k C k C à SV-673 tle at B Tugaloo River Watershed n w (03060102-060) to s s a Lake r Sumter National Yonah B Forest SV-358 $ T u g a k l o C k o C e s o n n o g t r n a o B L r r e B y r G R iv er $ Water Quality Monitoring Sites à Biological Monitoring Sites Highways SV-200 Streams $ /(1 2 3 Rail lines Lake County Lines Hartwell Lakes SCDHEC 11-Digit Hydrologic Units Public Lands N 2 0 2 Miles Chauga River Watershed (03060102-120) O r e s M i !"28 ll 37-N04 V rC 1 0 7 i k l !" l a g e 37-N02 r# Oconee C SC0024872 k State Park k C à J er ry SV-675 C h a u g 2 8 a !" Sumter National Forest $ Water Quality Monitoring Sites à Biological Monitoring Sites R # i NPDES Permits v e Ck r ar r Natural Swimming Areas ed C Rail lines Highways Modeled Streams Streams C R h Lakes a -

Natural Systems

Natural Systems NATURAL SYSTEMS INTRODUCTION Natural resources in Southwest Florida have had a major influence on the area’s economic development and growth. The most important of these resources are the Region’s location and climate, land and water resources, vegetation and wildlife, and inland and tidal wetlands. These resources have attracted the large number of retirees and tourists to the region, thereby fueling the area’s service, trade, and construction industries. THE CLIMATE Temperature Due to the Region's southerly location, a near-subtropical climate with an associated high annual rainfall is typical. Average monthly temperatures range from 64.3 degrees Fahrenheit in January to 82.6 degrees Fahrenheit in August. Freezes are not common in the Region, but may occur once or twice a year. "Jacket weather" occurs periodically during the fall and winter months. Weather and climate are very important factors in the economy of Southwest Florida. The combination of warm weather, decreased humidity, and low rainfall during the winter months encourages tourism and an influx of seasonal residents. A high yearly rainfall and moderate winter temperatures enable agriculture to thrive year-round. Periods of freezing weather, when they occur, have adverse effects upon the local economy. Unusually severe winter freezes and resulting agricultural losses in other parts of the state have caused a migration of agricultural interests into the Region from counties to the north. Precipitation Patterns Patterns of precipitation in Southwest Florida exhibit strong seasonal variations. The Region enjoys a rainy season from May through October and a dry season from November through April. Increased atmospheric moisture and incoming solar radiation levels in May generally trigger the rainy season, while a reversal of these conditions occurs in September to signal the start of the dry season.