Boek A0 Trusting Associations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Raging Grannies Songbook, Changes by Phyllis Noble, 2010, & Rebecca Alwin, 2016

Stichting Laka: Documentatie- en onderzoekscentrum kernenergie De Laka-bibliotheek The Laka-library Dit is een pdf van één van de publicaties in This is a PDF from one of the publications de bibliotheek van Stichting Laka, het in from the library of the Laka Foundation; the Amsterdam gevestigde documentatie- en Amsterdam-based documentation and onderzoekscentrum kernenergie. research centre on nuclear energy. Laka heeft een bibliotheek met ongeveer The Laka library consists of about 8,000 8000 boeken (waarvan een gedeelte dus ook books (of which a part is available as PDF), als pdf), duizenden kranten- en tijdschriften- thousands of newspaper clippings, hundreds artikelen, honderden tijdschriftentitels, of magazines, posters, video's and other posters, video’s en ander beeldmateriaal. material. Laka digitaliseert (oude) tijdschriften en Laka digitizes books and magazines from the boeken uit de internationale antikernenergie- international movement against nuclear beweging. power. De catalogus van de Laka-bibliotheek staat The catalogue of the Laka-library can be op onze site. De collectie bevat een grote found at our website. The collection also verzameling gedigitaliseerde tijdschriften uit contains a large number of digitized de Nederlandse antikernenergie-beweging en magazines from the Dutch anti-nuclear power een verzameling video's. movement and a video-section. Laka speelt met oa. haar informatie- Laka plays with, amongst others things, its voorziening een belangrijke rol in de information services, an important role in the Nederlandse anti-kernenergiebeweging. Dutch anti-nuclear movement. Appreciate our work? Feel free to make a small donation. Thank you. www.laka.org | [email protected] | Ketelhuisplein 43, 1054 RD Amsterdam | 020-6168294 Raging Grannies PDF Songbook - June 15, 2017 This document contains the complete library of songs and short-term songs. -

Madison Raging Grannies Songbook 4-28-2017.Pdf

Raging Grannies PDF Songbook - April 28, 2017 This document contains the complete library of songs and short-term songs. The songbook is updated as songs are revised and added. How to use the songbook - If you have an Internet connection, you can use the songbook on a computer, tablet or phone without downloading it. You can search the songbook online using Control F (PC) or Command F (Mac) and entering the name of the song or a phrase from the song you’re looking for. In the example below, 1) typing in “best democracy” found two places in the songbook where the phrase is used. 2) You can click on the link at the left that you want and jump to the song. If you want to download the songbook to your computer, right click the link and select "Save link as" (on a Windows computer) or “Download Linked File As” (on an Apple computer). 1 You can search the downloaded file using a search window. You can also download the songbook to a tablet or phone. The downloading process is different on each device. 2 Index of Songs — Raging Grannies of Madison — March 29, 2017 Short-term Songs ST 1 - Getting to Know You (2/13/17) Songs focused on Walker and Obama have been removed Library of Songs 1. Raging Grannies Theme Song (Doo Dah) 3. American Health Care System 4. Wasteful Military Spending (see also “Rounds” p. 32) 5. Uncle Richie’s SUV 6. Turkey in the Rain (1/12/15) 7. This Old Gray Granny (5/26/11) 8. -

Teaching Autoethnography: Personal Writing in the Classroom Melissa Tombro SUNY Fashion Institute of Technology

SUNY Geneseo KnightScholar Open SUNY Textbooks Open Educational Resources 2016 Teaching Autoethnography: Personal Writing in the Classroom Melissa Tombro SUNY Fashion Institute of Technology Follow this and additional works at: https://knightscholar.geneseo.edu/oer-ost Part of the Communication Commons, Education Commons, and the English Language and Literature Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Tombro, Melissa, "Teaching Autoethnography: Personal Writing in the Classroom" (2016). Open SUNY Textbooks. 7. https://knightscholar.geneseo.edu/oer-ost/7 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Educational Resources at KnightScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open SUNY Textbooks by an authorized administrator of KnightScholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Teaching Autoethnography: Personal Writing in the Classroom Teaching Autoethnography: Personal Writing in the Classroom Melissa Tombro Open SUNY Textbooks ©2016 Melissa Tombro ISBN: 978-1-942341-21-5 ebook This publication was made possible by a SUNY Innovative Instruction Technology Grant (IITG). IITG is a competitive grants program open to SUNY faculty and support staff across all disciplines. IITG encourages development of innovations that meet the Power of SUNY’s transformative vision. Published by Open SUNY Textbooks, Milne Library (IITG PI) State University of New York at Geneseo, Geneseo, NY 14454 This book was produced using Pressbooks.com, and PDF rendering was done by PrinceXML. Teaching Autoethnography: Personal Writing in the Classroom by Melissa Tombro is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted. -

Raging Grannies PDF Songbook

Raging Grannies PDF Songbook This document contains the complete library of songs as of 1/28/2017. The songbook will be updated as songs are revised and added. How to use the songbook - If you have an Internet connection, you can use the songbook on a computer, tablet or phone without downloading it. You can search the songbook online using Control F (PC) or Command F (Mac) and entering the name of the song or a phrase from the song you’re looking for. In the example below, 1) typing in “best democracy” found two places in the document where the phrase is used. 2) You can click on the link you want and jump to the song. If you want to download the songbook to your computer, right click the link and select "Save 1 link as" (on a Windows computer) or “Download Linked File As” (on an Apple computer). You can search the downloaded file using a search window. You can also download the songbook to a tablet or phone. The process is different on each device. 2 1 Index of Songs — Raging Grannies of Madison — January, 2016 1. Raging Grannies Theme Song (Doo Dah) 2. What Do We Want from Obama? 3. American Health Care System 4. Wasteful Military Spending (see also “Rounds” p. 32) 5. Uncle Richie’s SUV 6. Turkey in the Rain (1/12/15) 7. This Old Gray Granny (5/26/11) 8. Take Me Out of the War Game 8A Take Me Out of the War Game (8/26/12) 9. Raging Grannies are Conspiring (2/13/13) 10. -

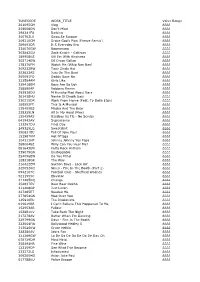

TUNECODE WORK TITLE Value Range 261095CM

TUNECODE WORK_TITLE Value Range 261095CM Vlog ££££ 259008DN Don't Mind ££££ 298241FU Barking ££££ 300703LV Swag Se Swagat ££££ 309210CM Drake God's Plan (Freeze Remix) ££££ 289693DR It S Everyday Bro ££££ 234070GW Boomerang ££££ 302842GU Zack Knight - Galtiyan ££££ 189958KS Kill Em With Kindness ££££ 302714EW Dil Diyan Gallan ££££ 178176FM Watch Me (Whip Nae Nae) ££££ 309232BW Tiger Zinda Hai ££££ 253823AS Juju On The Beat ££££ 265091FQ Daddy Says No ££££ 232584AM Girls Like ££££ 329418BM Boys Are So Ugh ££££ 258890AP Robbery Remix ££££ 292938DU M Huncho Mad About Bars ££££ 261438HU Nashe Si Chadh Gayi ££££ 230215DR Work From Home (Feat. Ty Dolla $Ign) ££££ 188552FT This Is A Musical ££££ 135455BS Masha And The Bear ££££ 238329LN All In My Head (Flex) ££££ 155459AS Bassboy Vs Tlc - No Scrubs ££££ 041942AV Supernanny ££££ 133267DU Final Day ££££ 249325LQ Sweatshirt ££££ 290631EU Fall Of Jake Paul ££££ 153987KM Hot N*Gga ££££ 304111HP Johnny Johnny Yes Papa ££££ 2680048Z Willy Can You Hear Me? ££££ 081643EN Party Rock Anthem ££££ 239079GN Unstoppable ££££ 254096EW Do You Mind ££££ 128318GR The Way ££££ 216422EM Section Boyz - Lock Arf ££££ 325052KQ Nines - Fire In The Booth (Part 2) ££££ 0942107C Football Club - Sheffield Wednes ££££ 5211555C Elevator ££££ 311205DQ Change ££££ 254637EV Baar Baar Dekho ££££ 311408GP Just Listen ££££ 227485ET Needed Me ££££ 277854GN Mad Over You ££££ 125910EU The Illusionists ££££ 019619BR I Can't Believe This Happened To Me ££££ 152953AR Fallout ££££ 153881KV Take Back The Night ££££ 217278AV Better When -

“Living the Dream”: a History of the Martin Luther King Jr. Holiday

“Living the Dream”: A History of the Martin Luther King Jr. Holiday by Daniel Thomas Fleming BA (La Trobe), PG-Dip (Melbourne) MA (Melbourne) A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Humanities and Social Sciences Faculty of Education and Arts University of Newcastle September 2015 Statement of Originality This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. I give consent to the final version of my thesis being made available worldwide when deposited in the University’s Digital Repository, subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act of 1968. Daniel Thomas Fleming 18 September 2015 ii Acknowledgements Essential to writing a thesis is the support of colleagues, friends and family. Inevitably, many expressions of thanks are due. First, I thank Associate Professor Michael Ondaatje, who supervised with intelligence and who always encouraged me to see the big picture. I also thank Professor Philip Dwyer for his guidance and help in maintaining my inspiration. Many others also encouraged me: Associate Professor Michelle Arrow; Dr Katherine Ellinghaus; Dr Karen McClusky; Professor John Hirst; Professor Mary L. Spongberg, Associate Professor Chris Dixon and Associate Professor Sarah Gregson. To those closer to my field of study, I thank Dr Clare Corbould and Professor Tim Minchin; and in the United States, Professor Glenn Eskew, Fath Davis Ruffins, Dr Vicki Crawford and Laura T. -

Illicit Lotto Popular in Kuwait

SUBSCRIPTION TUESDAY, MARCH 11, 2014 JAMADA ALAWWAL 10, 1435 AH www.kuwaittimes.net Mexico confirms Islamists free Black Twitter Bulls beat killing of ‘dead’ 13 nuns in rare growing into Heat in OT; drug kingpin7 prisoner13 swap online27 force Mavs20 roll Games of chance: Illicit Max 28º Min 20º lotto popular in Kuwait High Tide 09:18 & 18:52 Low Tide Underground betting, gambling flourishing 02:37 & 13:27 40 PAGES NO: 16101 150 FILS By Ben Garcia the lotto agents. Players often use birth- conspiracy theories days, anniversaries and other important KUWAIT: The 1st and the 16th of every dates in the calendar as their numbers of month are exciting days for Jennifer and choice. Others pick numbers randomly, Enlighten us Jayanti. They look forward to them all from street signs or bus numbers or TV month long, hoping and praying that commercials. one day their number will hit. Like many “I collect numbers from anything expats within the South Asian and under the sun. I remember I was riding in Filipino communities in Kuwait, the two the bus one time, I saw some numbers expats play Thai lotto regularly though written on the wall of the bus. I used gambling is illegal in Kuwait. Kuwait them on my betting pad, then the fol- By Badrya Darwish Times spoke with a few bettors to learn lowing day it landed in the lottery bet more about how it works and why they because it was the 15th of the month, play. the last day of betting. I gave that num- In Thai lottery, players are allowed to ber to my lottery agent and the next day, bet starting with 250 fils and can place I won. -

Songs by Artist

SBI Karaoke Songs by Artist Karaoke Shack Song Books Title DiscID Title DiscID 10 Years 2 Chainz & Nicki Minaj Through The Iris SBI-21020 I Love Dem Strippers (Explicit) (Duet) SBI-25892 Wasteland SBI-24179 2 Chainz & Pharrell Williams 10,000 Maniacs Feds Watching (Explicit) SBI-27905 More Than This SBI-15953 2 In A Room 10000 Maniacs Wiggle It SBI-17754 More Than This SBI-15953 2 Unlimited 10cc Get Ready For This SBI-03549 Don't Turn Me Away SBI-03473 Twilight Zone SBI-01229 Feel The Love SBI-03493 21 Savage & Offset & Metro Boomin' & Travis Scott (Duet) Food For Thought SBI-03498 Ghostface Killers (Explicit) SBI-32698 Life Is A Minestrone SBI-03486 2am Club One Two Five SBI-03472 Too Fucked Up To Call (Explicit) SBI-27401 People In Love SBI-03496 2Pac Silly Love SBI-03494 Changes SBI-07950 Woman In Love SBI-03495 Dear Mama SBI-03949 Woman In Love, A SBI-03495 I Get Around SBI-16687 12 Stones I Get Around SBIA-16632 Way I Feel SBI-18123 So Many Tears SBI-04217 Way I Feel, The SBI-18123 2Pac & Dr. Dre 1975 California Love SBI-04883 Chocolate SBI-27596 2Pac & Elton John City, The SBI-27799 Ghetto Gospel SBI-13962 Love Me SBI-29922 2Pac & Eric Williams Robbers SBI-28878 Do For Love SBI-07275 Settle Down SBI-28636 2Pac & K-Ci & JoJo Sex (Explicit) SBI-28074 How Do U Want It SBI-05238 1975, The 3 Doors Down Chocolate SBI-27596 Away From The Sun SBI-12395 City, The SBI-27799 Dangerous Game SBI-12396 Girls (Clean) SBIA-28327 Duck And Run SBI-13121 Love Me SBI-29922 Going Down In Flames SBI-12397 Robbers SBI-28878 Let Me Go SBI-16108 Robbers