Spatial Taste Formation As a Place Marketing Tool: the Case of Live Music Consumption

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE MANCHESTER WEEKENDER 14 Th/15 Th/16 Th/OCT

THE MANCHESTER WEEKENDER 14 th/15 th/16 th/OCT Primitive Streak Happy Hour with SFX Dr. Dee and the Manchester All The Way Home Infinite Monkey Cage Time: Fri 9.30-7.30pm, Sat 9.30-3.30pm Time: 5.30-7pm Venue: Royal Exchange Underworld walking tour Time: Fri 7.15pm, Sat 2.30pm & 7.15pm Time: 7.30pm Venue: University Place, & Sun 11-5pm Venue: Royal Exchange Theatre, St Ann’s Square M2 7DH. Time: 6-7.30pm Venue: Tour begins at Venue: The Lowry, The Quays M50 University of Manchester M13 9PL. Theatre, St Ann’s Square, window display Cost: Free, drop in. Harvey Nichols, 21 New Cathedral Street 3AZ. Cost: £17.50-£19.50. booking via Cost: Free, Booking essential through viewable at any time at Debenhams, M1 1AD. Cost: Ticketed, book through librarytheatre.com, Tel. 0843 208 6010. manchestersciencefestival.com. 123 Market Street. Cost: Free. jonathanschofieldtours.com. Paris on the Irwell Good Adolphe Valette’s Manchester Time: 6.30-8.30pm Venue: The Lowry, The Quays M50 3AZ. Cost: Free, Víctor Rodríguez Núñez Time: Fri 7.30pm, Sat 4pm & 8pm Time: 4-5.30pm Venue: Tour begins at booking essential thelowry.com. Time: 6.30pm Venue: Instituto Cervantes, Venue: Royal Exchange Theatre, Manchester Art Gallery, Mosley Street, 326-330 Deansgate M3 4FN. Cost: Free, St Ann’s Square M2 7DH. Cost: £9-£33, M2 4JA. Cost: Ticketed, book through booking essential on 0161 661 4200. book through royalexchange.org.uk. jonathanschofieldtours.com. Culture Gym Unlocking Salford Quays Subversive Stitching Alternative Camera Club Crafternoon Tea Time: Various Venue: The Quays Cost: Time: 11am Venue: Meet in the foyer Time: 10am-12pm & 3-5pm Venue: Time: 11am-1pm Venue: Whitworth at The Whitworth £2.50. -

Cultural Strategy Business Plan 221206.Doc This Business Plan Is a Draft and Is Still Subject to Alteration

This Business Plan is a draft and is still subject to alteration. This plan is not scheduled for completion until March 2007 Appendix 1 Cultural Strategy, Strategic Marketing, Events and Visitor Services. Cultural Services Chief Executive’s Department Draft Business Plan 2007/08-2009/10 1 H:\CommitteeServices\O&S REPORTS\SocStrat\Jan 07\Appendix 1 Cultural Strategy Business Plan 221206.doc This Business Plan is a draft and is still subject to alteration. This plan is not scheduled for completion until March 2007 Part One: Context: Introduction from the Strategic Director, Eamonn Boylan, and Lead Executive Member, Councillor Mark Hackett Manchester has a proud history of creativity and innovation. Essential to our ambition to become a world-class city is the priority to deliver high quality cultural services that directly contribute to the economic success of the city and enable people to reach their full potential. Cultural activities, sports, parks and open spaces enrich local neighbourhoods, provide opportunities for individuals to participate, to acquire skills, and to build good relationships with each other. The successful delivery of the priorities of the city’s Cultural Strategy has been largely achieved by strong partnership working with the public, private and voluntary sectors as part of the Manchester Cultural Partnership. The development of brand Manchester—the original modern city—and a vibrant calendar of city centre and community-based events enhances the reputation of the city, attracts increasing numbers of visitors, creating wealth and employment opportunities, positioning Manchester as a modern European city—a cultural destination. The Cultural Services Division comprises Libraries and Theatres, City Galleries, Sport and Leisure Services, Cultural Strategy, Strategic Marketing and Events and Visitor Services. -

Chamber Music Concerts Player and Chamber Musician with the Tempest Two Concerts Featuring Rounds for Brass Quintet, Flute Trio

We are Chamber Music We are Opera and Song We are Popular Music Our Chamber Music Festival goes to the city Again in Manchester Cathedral, we will be Following its success at the Royal Albert Hall and Welcome centre (10-12 Jan) using Manchester Cathedral taking the magic and mystery of Orpheus with here at the RNCM last term, the RNCM Session as our hub, and featuring the Academy of Gluck’s Orfeo ed Euridice (28 Mar), which Orchestra returns with an exciting eclectic Ancient Music, the Talich Quartet and The will also be performed alongside his witty programme (25 Apr). Staff-led Vulgar Display Band of Instruments together with our staff The Drunkard Cured (L’ivrogne corrigé) in our give us their take on extreme metal (12 Feb). to the and students, to explore ‘The Art of Bach’. exclusive double-bill in the intimacy of our Our faithful lunchtime concert followers need not worry about the temporary closure of our Studio Theatre (18, 20, 22 and 27 Mar). Opera We are Folk and World Spring Concert Hall. These concerts will be as frequent, Scenes are back (21, 24, 28 and 31 Jan), as Fusing Latin American and traditional Celtic diverse and delightful as ever, in fantastic venues entertaining as ever. Yet another exciting venture folk, Salsa Celtica appear on the RNCM stage such as the Holden Art Gallery, St Ann’s is the one with the Royal Exchange Theatre for (7 Mar), followed by loud, proud acoustic season at Church and the Martin Harris Centre, featuring an extra-indulgent Day of Song (27 Apr) where Bellowhead–founding members, Spiers & the RNCM Chamber Ensemble with Stravinsky’s we will be taking you with us through the lush Boden on their last tour as a duo (20 Mar), The Soldier’s Tale, as well as a feast of other atmosphere of the Secession and travelling from while the award-winning folk band Melrose ensembles: Harp, Saxophone, Percussion and country to country by song throughout the day. -

Enjoy Free Travel Around Manchester City Centre on a Free

Every 10 minutes Enjoy free travel around (Every 15 minutes after 6:30pm) Monday to Friday: 7am – 10pm GREEN free QUARTER bus Manchester city centre Saturday: 8:30am – 10pm Every 12 minutes Manchester Manchester Victoria on a free bus Sunday and public holidays: Arena 9:30am – 6pm Chetham’s VICTORIA STATION School of Music APPROACH Victoria Every 10 minutes GREENGATE Piccadilly Station Piccadilly Station (Every 15 minutes after 6:30pm) CHAPEL ST TODD NOMA Monday to Friday: 6:30am – 10pm ST VICTORIA MEDIEVAL BRIDGE ST National Whitworth Street Sackville Street Campus Saturday: 8:30am – 10pm QUARTER Chorlton Street The Gay Village ootball Piccadilly Piccadilly Gardens River Irwell Cathedral Chatham Street Manchester Visitor Every 12 minutes useum BAILEYNEW ST Information Centre Whitworth Street Palace Theatre Sunday and public holidays: orn The India House 9:30am – 6pm Exchange Charlotte Street Manchester Art Gallery CHAPEL ST Salford WITHY GROVEPrintworks Chinatown Portico Library Central MARY’S MARKET Whitworth Street West MMU All Saints Campus Peak only ST Shudehill GATE Oxford Road Station Monday to Friday: BRIDGE ST ST Exchange 6:30 – 9:10am People’s Suare King Street Whitworth Street West HOME / First Street IRWELL ST History Royal Cross Street Gloucester Street Bridgewater Hall and 4 – 6:30pm useum Barton Exchange Manchester Craft & Manchester Central DEANSGATE Arcade/ Arndale Design Centre HIGH ST Deansgate Station Castlefield SPINNINGFIELDS St Ann’s Market Street Royal Exchange Theatre Deansgate Locks John Suare Market NEW Centre -

≥ Concerts Society (A Charitable Company Limited by Guarantee)

≥ ConCerts soCiety (A Charitable Company Limited by Guarantee) Annual report and summary Financial statements for the year ended 31 March 2011 Company number 62753 Charity number 223882 the Hallé Concerts society gratefully acknowledges the financial assistance of Arts Council england, Manchester City Council, the Association of Greater Manchester Authorities and Musicians Benevolent Fund. trUSTEES’ rePORT AnD sUMMARY FinAnCiAL STAteMENTS For tHe yeAr enDeD 31 MArCH 2011 reference and Administrative details ..........................................................................................................................................................................................2 Chairman’s report ....................................................................................................................................................................................................................................3 Chief executive’s review of the year .......................................................................................................................................................................................4–7 trustees’ report ...............................................................................................................................................................................................................................8–12 independent auditor’s statement to the members of Hallé Concerts society .....................................................................................................13 -

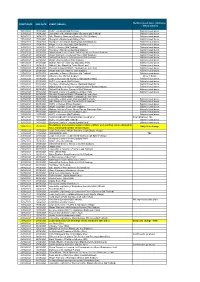

DATE END DATE EVENT (VENUE) Behind Closed Doors / Audience

Behind closed doors / Audience START DATE END DATE EVENT (VENUE) / Virtual (online) 15/04/2021 15/04/2021 MUFC v Granada (Old Trafford) Behind closed doors 15/04/2021 18/04/2021 Lancashire v Northamptonshire (Emirates Old Trafford) Behind closed doors 16/04/2021 16/04/2021 Sale Sharks v Gloucester Rugby (AJ Bell Stadium) Behind closed doors 17/04/2021 17/04/2021 Stockport v Maidenhead (Edgely Park) Behind closed doors 17/04/2021 17/04/2021 Rochdale v Accrington Stanley (Spotland Stadium) Behind closed doors 17/04/2021 17/04/2021 Wigan v Crewe Alexandra (DW Stadium) Behind closed doors 18/04/2021 18/04/2021 MUFC v Burnley (Old Trafford) Behind closed doors 20/04/2021 20/04/2021 Rochdale v Blackpool (Spotland Stadium) Behind closed doors 20/04/2021 20/04/2021 Bolton Wanderers v Carlisle Utd (University of Bolton Stadium) Behind closed doors 22/04/2021 22/04/2021 Wigan Warriors v Castleford Tigers (DW Stadium) Behind closed doors 23/04/2021 23/04/2021 Salford Red Devils v Centurions (AJ Bell Stadium) Behind closed doors 24/04/2021 24/04/2021 Wigan v Burton Albion (DW Stadium) Behind closed doors 24/04/2021 24/04/2021 Oldham Athletic v Grimsby (Boundary Park) Behind closed doors 24/04/2021 24/04/2021 Salford City v Mansfield Town (Moor Lane) Behind closed doors 29/04/2021 29/04/2021 Potential European Match - Champs Lge semi-final Behind closed doors 29/04/2021 29/04/2021 Wigan Warriors v Hull FC (DW Stadium) Behind closed doors 29/04/2021 02/05/2021 Lancashire v Sussex (Emirates Old Trafford) Behind closed doors 30/04/2021 30/04/2021 Billionaire -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE Dr. Justin O'Connor 1 Academic Qualifications 1989 D. Phil. University of Sussex. French Intellectuals and the People: 1820- 1939 1982 MA in Social and Political Thought, University of Sussex. Thesis: Intellectuals and the Popular Front in France 1980 BA(Hons) History and Politics, University of Kent at Canterbury 2 Employment History Oct.2008 - Research Capacity Professor, Creative Industries Faculty, Queensland University of Technology, Australia Sept. 2006 Professor of Cultural Industries, School of Performance and Cultural Sept. 2008 Industries, University of Leeds June 2000 - Reader in Sociology, Manchester Metropolitan University Aug 2006 Sept. 1995 - Lecturer in Sociology, Manchester Metropolitan University June 2000 May 1995- Director, Institute for Popular Culture, Manchester Metropolitan University Sept. 2006 Oct. 1991- Research Fellow, Institute for Popular Culture, Manchester May 1995 Metropolitan University 1989-90 Research Assistant, Centre for Employment Research, Manchester Polytechnic (‘Economic Impact of the Cultural Industries in Greater Manchester’) 1988 - 1991 Lecturer (p/t) Manchester Polytechnic Other Academic Positions Editorial board Chinese Academy of Social Science annual publication on ‘The Creative Economy: International and Chinese Perspectives’ Editorial Board: Research on Marxist Aesthetics (Shanghai Jiaotong University) Editorial Board: Culture Unbound (on-line Journal) Editorial Board: Art and the Public Sphere Member of International Advisory Board, Centre for Popular Culture, University -

Come and Play with the Hallé Strictly Hallé

COME AND PLAY WITH THE HALLÉ CONCERTS FOR SCHOOLS STRICTLY HALLÉ CONDUCTED BY JONATHON HEYWARD PRESENTED BY TOM REDMOND SUMMER 2018 THE BRIDGEWATER HALL, MANCHESTER RESOURCE PACK FOR TEACHERS Supported by: © Hallé Concerts Society 2018 COME AND PLAY WITH THE HALLÉ 2018 STRICTLY HALLÉ CONDUCTED BY JONATHON HEYWARD PRESENTED BY TOM REDMOND TCHAIKOVSKY Swan Lake: Prelude to Act II TCHAIKOVSKY The Nutcracker: Waltz of the Flowers * Audience Participation {Instrumental} COPLAND Rodeo: Hoedown * MARY GREEN & JULIE STANLEY Ai Caramba Samba Audience Participation {Song} SAINT-SAENS Danse Macabre PICKETT/BENNISON Charleston Champions Audience Participation {Song} DVORAK Slavonic Dance: (Audience choice) Op 46, No 8 in G minor Op 72, No 2 in E minor PRADO Mambo No. 5 Audience Participation {Instrumental} arr. PICKETT British Folk Dance Suite Audience Participation MARQUEZ Danzón No. 2 *BBC 10 Pieces JONATHON HEYWARD (conductor) Jonathon Heyward is forging a career as one of the most exciting conductors of his generation. Currently Assistant Conductor of the Hallé, alongside Music Director Sir Mark Elder, and also Music Director of the Hallé Youth Orchestra, the young American has also been selected to be part of the Los Angeles Philharmonic’s 2017–18 Dudamel Conducting Fellowship programme. In addition to conducting his first subscription series concerts with the Hallé in Manchester, this season also sees him embark on a number of eclectic projects: five performances premiering Giorgio Battistelli’s new opera, Lazarus, for the Birmingham Opera Company with stage director Graham Vick; a tour of France with the Orchestre de l’Opéra de Rouen, including performances at the festivals in Besançon and La Chaise-Dieu; a series of concerts with the Flanders Symphony Orchestra at the best halls across Belgium; debuts with the Orchestre National de Bordeaux-Aquitaine, Orchestre National des Pays de la Loire and Orchestre de Chambre de Lausanne; and a return invitation to Japan. -

2009/10 Manchester Concert Series Series Concert Manchester 2009/10 at a Glance a At

www.manchestercamerata.co.uk THE BRIDGEWATER HALL & ROYAL NORTHERN COLLEGE OF MUSIC OF COLLEGE NORTHERN ROYAL & HALL BRIDGEWATER THE 2009/10 MANCHESTER CONCERT SERIES CONCERT MANCHESTER 2009/10 2009/10 MANCHESTER CONCERT SERIES AT A GLANCE SATURDAY 26 SEPTEMBER 2009 FRIDAY 1 JANUARY 2010 RNCM BRIDGEWATER HALL Cimarosa, De Falla, Mendelssohn New Year’s Day Viennese Gala Jaime Martin/Guy Eshed/Carolina Krogius Gábor Tákacs-Nagy/Natalya Romaniw/ Michael Gurevich FRIDAY 9 OCTOBER 2009 BRIDGEWATER HALL SATURDAY 23 JANUARY 2010 Alwyn, Beethoven, Brahms RNCM Douglas Boyd/Jonathan Biss/Rachael Clegg Handel’s Belshazzar Nicholas Kraemer/Robin Blaze SATURDAY 31 OCTOBER 2009 RNCM SATURDAY 30 JANUARY 2010 Golijov, Piazzolla, Villa-Lobos, Shostakovich BRIDGEWATER HALL Gordan Nikolitch Beethoven, Mahler Douglas Boyd/Jane Irwin/Peter Wedd THURSDAY 31 DECEMBER 2009 BRIDGEWATER HALL MONDAY 1 FEBRUARY 2010 New Year’s Eve Gala RNCM Clark Rundell/Rebecca Bottone/ Manchester Composers’Project workshop day Bonaventura Bottone SATURDAY 13 MARCH 2010 BRIDGEWATER HALL Haydn, Stravinsky, Beethoven Richard Farnes/Valeriy Sokolov SATURDAY 27 MARCH 2010 RNCM Chopin, Schubert Martin Roscoe/Manchester Camerata Ensemble SATURDAY 24 APRIL 2010 RNCM Debussy, Berlioz, Brahms Douglas Boyd/Sarah Tynan SATURDAY 22 MAY 2010 BRIDGEWATER HALL Mozart, Haydn Douglas Boyd/Kathryn Stott Published by Manchester Camerata, April 2009. Artists and programmes correct at the time of going to press but may be subject to alteration. MANCHESTER CAMERATA LTD , RNCM, 124 Oxford Road, Manchester M13 9RD Tel: 0161 226 8696 Registered Charity No. 503675 [email protected] www.manchestercamerata.co.uk WELCOME TO OUR 2009/10 ‘EXCHANGES’ SEASON SATURDAY 26 SEPTEMBER 2009 FRIDAY 9 OCTOBER 2009 LOVE, THE MAGICIAN LEGENDS Welcome to Manchester Camerata's new season - your chance to experience the RNCM CONCERT HALL THE BRIDGEWATER HALL atmosphere, creativity and commitment that is encapsulated in all Camerata's events. -

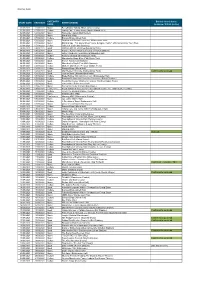

Date End Date Category Name Event

Classified: Public# CATEGORY Behind closed doors / START DATE END DATE EVENT (VENUE) NAME Audience / Virtual (online) 01/09/2021 12/09/2021 Music Everybody's Talking About Jamie (Lowry) 01/09/2021 01/09/2021 Culture Jimmy Carr: Terribly Funny (Apollo Manchester) 02/09/2021 02/09/2021 Music Passenger (Apollo Manchester) 02/09/2021 02/09/2021 Music Black Midi (Ritz) 03/09/2021 03/09/2021 Culture Bongos Bingo (Albert Hall) 03/09/2021 03/09/2021 Music Dr Hook with Dennis Locorriere (Bridgewater Hall) 03/09/2021 03/09/2021 Music Black Grape - "It's Great When You're Straight... -

Barbirolli Square

SECTION NAME 1OO BARBIROLLI SQUARE 1 1OO BARBIROLLI SQUARE Contents Exposition 4-7 History Into the Rhythm 8-11 Connectivity Location Increase your Tempo 12-15 The Studio Showtime 16-17 Level 01 Work in Harmony 18-27 Specification Building Stacker Floor Plans Crescendo 28-33 Places to Explore Amenity Map www.100barbirolli.co.uk Society 2 1OO BARBIROLLI EXPOSITION | HISTORY Exposition 1819 — 2020 1819 —MANCHESTER 1943 —MANCHESTER On the 16th of August 1819, 80,000 people John Barbirolli, a conductor and cellist, came together in St Peter's Field to support brought together a diverse collection of prominent advocates of electoral reform. talent. An orchestra that any city would be Together they fought for their voices to be proud of. In just two months he had created heard and their peaceful protest became the now world-famous Hallé orchestra. part of the story of Manchester. An orchestra that would present a sense From 1820 the site which is now Barbirolli of glory and revival in the middle of the Square was home to textile businesses and largest conflict the world had ever seen. this manufacturing heritage is still visible An orchestra that featured a schoolboy, in our immediate neighbourhood over a headmistress and veterans. Together they century later. created something special. ↰ JOHN BARBIROLLI JOHN master conductor ↰ THE HALLÉ ORCHESTRA & renegade 4 5 1OO BARBIROLLI EXPOSITION | HISTORY 2020 —MANCHESTER Something special returns: 100 Barbirolli Square. A collaborative space for: the determined, the believers and the collaborators. Whoever you are, wherever you are from, 100 Barbirolli Square is an environment that will nurture you and your skills. -

Manchester City Centre

approx. 20 & 10 minutes by Metrolink from Victoria Manchester Arndale Opening Times Shops Mon to Fri - 9am to 8pm Sat - 9am to 7pm Sun - 11.30am to 5.30pm Foodcourt Etihad Mon to Sat - 7am to 8pm Campus Manchester City Centre NOMA Sun - 9am to 7pm A newly developed 20 acre Welcome! Manchester’s compact city centre contains lots to do in a Bank Holiday opening times may vary. site combining offices, shops, small space. To help, we’ve colour coded the city. Explore and enjoy! Visit manchesterarndale.com for details hotels and homes. Find us on The Etihad Central Retail District Northern Quarter The Gay Village Featuring the biggest Manchester’s creative, urban Unique atmosphere with names in fashion, including heart with independent fashion restaurants, bars and clubs high street favourites. stores, record shops and cafés. around vibrant Canal Street. Petersfield Piccadilly Spinningfields Manchester Central Convention The main gateway into A newly developed quarter Complex, The Bridgewater Hall Manchester, with Piccadilly train combining retail, leisure, and Great Northern. station and Piccadilly Gardens. business and public spaces. Chinatown Castlefield Oxford Road Made up of oriental businesses The place to escape from the Home to the city’s two including Chinese, Thai, Japanese hustle and bustle of city life universities and a host and Korean restaurants. with waterside pubs and bars. of cultural attractions. Job Centre Plus Urban Exchange University n Place o t l r o h C e s r & t e t n m u e a n C i h y c m t n i i 5 C r 1 t l m & A o 5 r & f 2 s k y & n a i 5 l u 1 o Q .