Cora Ginsburg Llc Titi Halle Owner

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Great Lakes Region Seminar

Great Lakes Region Seminar April 11–15, 2021 Appleton, Wisconsin Hosted by the Fox Valley Embroiderers’ Guild A chapter of the Embroiderers’ Guild of America An Invitation to Vision of Stitches Vision can be defined as having the ability to see or the ability to think or plan with imagination; both definitions encompass our love of the needle arts. The Fox Valley Embroiderers’ Guild invites you to join us for Vision of Stitches, to be held at the Red Lion Hotel Paper Valley in downtown Appleton, Wisconsin, April 11–15, 2021. With inspiring faculty and classes, wonderful accommodations and food, as well as an exciting night out, we are looking forward to sharing our community with you. Of course, we will have the seminar favorites: a boutique presented by Needle Workshop of Wausau, Wisconsin, Merchandise Night and the GLR Members’ Needle Art Exhibit. We have teamed with Lions Clubs International to recycle used eyeglasses. Consider collecting used eyewear from your chapter members who are unable to join us. Looking forward to welcoming you to our Vision. Nancy Potter, Chairman, GLR Seminar, Vision of Stitches Brochure Contents Proposed Event Schedule 3 Registration Information 4 Process & Instructions Registration Fees and Class Confirmation Registrar’s Contact Information Hotel Registration 5 Seminar Cancellation Policy 5 Special Events 6 Boutique by The Needle Workshop of Wausau, Wisconsin Half-Day Classes: Sunday Meet the Teachers: Sunday Teachers’ Showcase: Monday Tuesday Night Out: Dinner at Pullmans at Trolley Square, featuring professor -

August 2021.Indd

Search Press Ltd August 2021 The Complete Book of patchwork, Quilting & Appliqué by Linda Seward www.searchpress.com/trade SEARCH PRESS LIMITED The world’s finest art and craft books ADVANCE INFORMATION Drawing - A Complete Guide: Nature Giovanni Civardi Publication 31st August 2021 Price £12.99 ISBN 9781782218807 Format Paperback 218 x 152 mm Extent 400 pages Illustrations 960 Black & white illustrations Publisher Search Press Classification Drawing & sketching BIC CODE/S AFF, WFA SALES REGIONS WORLD Key Selling Points Giovanni Civardi is a best-selling author and artist who has sold over 600,000 books worldwide No-nonsense advice on the key skills for drawing nature – from understanding perspective to capturing light and shade Subjects include favourites such as country scenes, flowers, fruit, animals and more Perfect book for both beginner and experienced artists looking for an inspirational yet informative introduction to drawing natural subjects This guide is bind-up of seven books from Search Press’s successful Art of Drawing series: Drawing Techniques; Understanding Perspective; Drawing Scenery; Drawing Light & Shade; Flowers, Fruit & Vegetables; Drawing Pets; and Wild Animals. Description Learn to draw the natural world with this inspiring and accessible guide by master-artist Giovanni Civardi. Beginning with the key drawing methods and essential materials you’ll need to start your artistic journey, along with advice on drawing perspective as well as light and shade, learn to sketch country scenes, fruit, vegetables, animals and more. Throughout you’ll find hundreds of helpful and practical illustrations, along with stunning examples of Civardi’s work that exemplify his favourite techniques for capturing the natural world. -

Project Description

Project Description Candlewicking is a form of surface embroidery that traditionally uses an unbleached cotton thread on a piece of unbleached muslin. It gets Candlewicking its name from the nature of the thread, which very much resembles the wick used in a candle. Motifs are created using a variety of knots (Colonial) and satin stiches (backstitich). A warm covering made of two layers of cloth filled with a material with loft and tyed together. Tying refers to the technique of using thread, Comforters yarn or ribbon to pass through all three layers of the comforter at reqular intervals. These "ties" hold the layers together during use and especially when the comforter is washed. A warm covering made of two layers of cloth filled with a material with Quilts loft and stitched together in lines or patterns. The top layer is typically pieced together and the bottom is one solid layer. Process of stitching together two layers of fabric, usually with a soft, thick substance placed between them. The layer of wool, cotton, or other stuffing provides insulation; the stitching keeps the stuffing evenly distributed and also provides opportunity for artistic expression. Quilting has long been used for clothing in many parts of the world, especially Quilting in the Far and Middle East and the Muslim regions of Africa. It reached its fullest development in the U.S., where it was at first popularly used for petticoats and comforters. By the end of the 18th century the U.S. quilt had distinctive features, such as coloured fabric sewn on the outer layers (appliqué) and stitching that echoed the appliqué pattern. -

Advanced Silk Shading

ROYAL SCHOOL OF NEEDLEWORK 2019-2020 ACADEMIC YEAR DIPLOMA ADVANCED SILK SHADING Traditionally worked with silk thread on silk or linen fabric, but now more usually worked in stranded cotton thread. Silk is still the most usual background fabric but a variety of other fabrics may be used. For Advanced Silk Shading you may work EITHER an animal, bird, fish or reptile; OR a tapestry shaded human figure. SILK SHADED ANIMAL OR BIRD AIM – To demonstrate an advanced level of technical skill by working a realistic and naturally shaded embroidery of an animal, fish, reptile or bird using Long and Short Stitch with one strand of stranded cotton (or fine silk thread). To utilise shading and stitch direction to accurately depict musculature, fur, scales and clearly defined feathers as appropriate. Please note: All preparatory work (e.g. outlines, drawings, stitch plans, original source material) MUST be handed in for assessment or the work will not be marked. DESIGN Try to come with some ideas for a design and bring along some photographs. The photograph must be printed a similar size to the embroidery size otherwise it is very difficult to work. It is essential to work from a crisp, clear, well-focused photograph where you can see the individual colours and changes from dark to light. Illustrations can sometimes be harder to follow, and you should be wary of images from the Internet, which are often poor quality and may not print sufficiently well. However there are many places online from which you can purchase high quality images. The tutor will be able to make suggestions and help you bring your ideas together. -

The Bayeux Tapestry

The Bayeux Tapestry The Bayeux Tapestry A Critically Annotated Bibliography John F. Szabo Nicholas E. Kuefler ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD Lanham • Boulder • New York • London Published by Rowman & Littlefield A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706 www.rowman.com Unit A, Whitacre Mews, 26-34 Stannary Street, London SE11 4AB Copyright © 2015 by John F. Szabo and Nicholas E. Kuefler All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Szabo, John F., 1968– The Bayeux Tapestry : a critically annotated bibliography / John F. Szabo, Nicholas E. Kuefler. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-4422-5155-7 (cloth : alk. paper) – ISBN 978-1-4422-5156-4 (ebook) 1. Bayeux tapestry–Bibliography. 2. Great Britain–History–William I, 1066–1087– Bibliography. 3. Hastings, Battle of, England, 1066, in art–Bibliography. I. Kuefler, Nicholas E. II. Title. Z7914.T3S93 2015 [NK3049.B3] 016.74644’204330942–dc23 2015005537 ™ The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992. Printed -

Altar Guild Handbook, Rev

HANDBOOK FOR ALTAR GUILDS Revised 2014 (Former versions entitled “Altar Guild Manual”) The Episcopal Diocese of Texas i The National Altar Guild Association (NAGA) The purpose of the National Altar Guild Association (NAGA) is to assist parish, diocesan, and provincial altar guilds through information, resources, and communication, including a quarterly newsletter—the EPISTLE www.nationalaltarguildassociation.org National Altar Guild Prayer Most gracious Father Who has called me Your child to serve in the preparation of Your Altar, so that it may be a suitable place for the offering of Your Body and Blood; Sanctify my life and consecrate my hands so that I may worthily handle Those Sacred Gifts which are being offered to You. As I handle holy things, grant that my whole life may be illuminated and blessed by You, in whose honor I prepare them, and grant that the people who shall be blessed by their use, May find their lives drawn closer to Him Whose Body and Blood is our hope and our strength, Jesus Christ our Lord. AMEN. Oh Padre bondadosa, que has llamado a tu hija(o) a sevir en la preparación de Tu Altar, para que sea un lugar digno para la Ofrenda de Tu Cuerpo y de Tu Sangre; Santifica mi vida y consagra mis manos para que de esta manera yo pueda encargarme dignamente de estos Dones Sagrados que te ofrecemos. Mientras sujeto estos santos objetos, concede que mi vida sea iluminada y santificada por Ti, en cuyo honor los preparo, y permite también que el pueblo bendecido por su participación, se una más a Él, Cuyo Cuerpo y Sangre son nuestra esperanza y nuestra fortaleza, Jesucristo nuestro Señor. -

How to Needlepoint

How to Needlepoint A quick guide for the on the go learner to get started stitching By Casey Sheahan What is needlepoint? Needlepoint is a type of embroidery where wool, cotton or silk is threaded through an open weave canvas. Needlepoint can be used to create many different objects, crafts or art canvases. Sources : Colorsheets, Viviva, and Shovava. “What Is Needlepoint? Learn the DIY Basics to Begin This Fun and Colorful Craft.” My Modern Met, 9 Sept. 2018, https://mymodernmet.com/what-is-needlepoint/. The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. “Needlepoint.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 4 Sept. 2019, https://www.britannica.com/art/needlepoint#:~:targetText=Needlepoint as it is known,the foundation for the embroidery Needlework has been around for centuries. Throughout history we have seen a variety of different types History of of stitching. Tapestries have been found dating back to the 15th century Needlepoint and needlepoint was even found in the cave of a Pharaoh. In the 17th century when upholstered furniture became pooular. Source: “The English Needlepoint.” Ghorbany, https://ghorbany.com/inspiration/the-english-needlepoint. Getting Started Now that you know a little more about the history of needlepoint, you will start collecting your materials to begin stitching. Getting Started Material Options: Threads and Yarns Althea DeBrule outlines some of the most common types of threads used in needlepoint. Persian Yarn: By far the most popular yarn used for needlepoint. Persian wool can be be purchased in hundreds of colors from delicate hues to bold shades. Tapestry Yarn: Tapestry wool is a single strand thread that cannot be separated for fine stitching. -

De Laudibus Legum Angliae

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com UNIVE NFORD UBRAR School of Law ह பல UL PREMY . JSN LFO XKD 1874 DE LAUDIBUS LEGUM ANGLIÆ A TREATISE IN COMMENDATION OF THE LAWS OF ENGLAND BY CHANCELLOR SIR JOHN FORTESCUE WITH TRANSLATION BY FRANCIS GREGOR NOTES BY ANDREW AMOS AND A LIFE OF THE AUTHOR BY THOMAS ( FORTESCUE ) LORD CLERMONT . CINCINNATI : ROBERT CLARKE & CO . 1874 Entered , according to act of Congress , in the year 1874 , By ROBERT CLARKE & CO . , In the office of the Librarian of Congress , at Washington . Stereotyped by OGDEN , CAMPBELL & Co. , Cin . , o . 93144 PUBLISHERS ' NOTICE . In carrying out our plans for the republication of some of the most noted “ Legal Classics , ” Sir John Fortescue's “ De Laudibus Legum Angliæ ” was selected as the third of our series , and the edition by Amos , published in 1825 , was fixed upon for republication . Just as we were about putting it into the printers ' hands , we fortunately heard of Lord Clermont's privately printed edition of Fortescue's Life and Works , in 2 vols . royal 4to , printed in 1869 , a detailed description of which will be found on page liv . After some correspondence we learned that the edition was a limited one - 120 copies — designed for family friends and important public libraries . On being informed of our in tended republication , and of our desire to refer to it for comparison , Lord Clermont generously sent to us a copy of this sumptuous work , for our use in the preparation of this edition , and then to be presented to the Public Library of Cincinnati . -

Basic Blackwork Class – HL Anja Snihová Camarni

Basic Blackwork Class – HL Anja Snihová Camarni I’m including in this handout a couple of different ways of explaining “how-to” in blackwork, because not every explanation works for every person. Also, please excuse the crass commercial plugs. I didn’t have time to completely re-write, so pretend that this somebody else’s. Which it is! Anja and MaryAnne are not the same person. <grin> MaryAnne Bartlett is a 21st century woman, making a living by writing and researching, designing and selling blackwork designs and products. Anja Snihova’ was born in the late 14th century and due to the potions that her alchemist husband makes, survived into the early 17th century! Beginning Blackwork Blackwork is a counted thread technique made popular in England in the 1500's by Catharine of Aragon, the Spanish first wife of King Henry VIII of England. It was immortalized in the incredibly detailed portraits done by the court painter, Hans Holbein, whose name is give to the stitch used, which is just a running stitch that doubles back on itself at the other end of its "journey". Blackwork can be anything from a simple line drawing to the complex pattern of #10 below, and on to designs so complex no one seems to know how to do them! It was usually done with silk thread on a white even-weave linen, and despite the name of the technique, was done in every colour of the rainbow, although black was the most popular colour, followed by red and blue. The most peculiar thing about this technique is that, done properly, the design repeats on both the right and wrong sides of the fabric, making it perfect for collars, cuffs, veils and ribbons where both sides need to look nice! Blackwork Embroidery Instructions 1. -

Sewing Fun! Feather

Sewing Fun! Feather. Blanket. Straight. Cross. Satin. Zig-zag. Chain. Running. Back. Whip. Slip. Knotting. These are not yoga poses! These are stitches that you can learn as you become a sewing master! Sewing is an essential skill that is practical and fun! Lose a button? No need to ask mom for help! You can fix it yourself! Want to create a personalized gift for someone? Sew it! Make your own bedroom accessories, stuffed animals, pencil cases, tote bags, blankets, pillows, doll clothes, design your own fashion. Dream it! Sew it! How to earn the Summer Reading patch the Girl Scout way: Steps: 1. Discover—Gather the materials you need and practice a few stitches. 2. Connect—Complete your first sewing project. 3. Take Action—Put your new skill to use! Materials Needed: In order to complete this patch, you’ll need a few things: • basic sewing supplies (See Step 1 for list or purchase an embroidery kit) • fabric: scraps or embroidery cloth • sewing resources: You can either go online with an adult, ask a professional, or visit your public library • a box or basket to use as your sewing kit • a quilting hoop • buttons STEP 1 Discover the basics of sewing. Before you start a project, it’s important to have all the tools you may need on hand. An easy way to gather everything is to create a sewing kit. Here are some items that you might want to have before you begin: • needles • thread • embroidery floss • needle threader • scissors • seam ripper • pins Optional: • measuring tools 800-248-3355 • marking tools gswpa.org • painter’s tape/colored tape (This is great for learning to sew straight lines!) Use your resources wisely to learn about hand sewing—you can find books about different kinds of stitches at your local library, or with the help of an adult, go online! There are websites and videos that can show you how to do easy, intermediate, and complicated stitches. -

PDF Download Hardanger Embroidery

HARDANGER EMBROIDERY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Donatella Ciotti | 96 pages | 03 May 2007 | Sterling Publishing Co Inc | 9781402732270 | English | New York, United States Hardanger Embroidery PDF Book Minimum monthly payments are required. Close Help Do you have a picture to add? Shipping and handling. I especially love the close-up pictures of examples of early-style Hardanger. She wore a crisp white apron UNDER her colorful daily one, so if company showed up, she could whisk off the colorful, but mussed up one and look presentable. I love the hardanger on the collar of a blouse. Email to friends Share on Facebook - opens in a new window or tab Share on Twitter - opens in a new window or tab Share on Pinterest - opens in a new window or tab. During the Renaissance , this early form of embroidery spread to Italy where it evolved into Italian Reticella and Venetian lacework. Condition see all. Hardanger kloster …. This amount is subject to change until you make payment. Ensure that the holes are facing stitches going outside; as shown in the picture above. Picture Information. If you take a shortcut and miss out a number on the diagram your stitches won't hold when you start the cutting process. Apparently wait list means go online and buy it quickly as the store does not wait for you to response to the email. Listed in category:. As you progress through the course, I introduce you to the different stitches that you need. However, that number can vary. The seller has not specified a shipping method to Germany. -

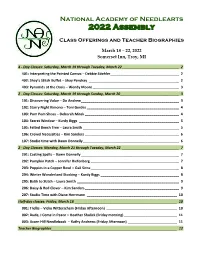

2022 Assembly

National Academy of Needlearts 2022 Assembly Class Offerings and Teacher Biographies March 18 – 22, 2022 Somerset Inn, Troy, MI 4 - Day Classes: Saturday, March 19 through Tuesday, March 22 _____________________________ 2 401: Interpreting the Painted Canvas ─ Debbie Stiehler ___________________________________ 2 402: Shay’s Stitch Buffet ─ Shay Pendray ______________________________________________ 2 403: Pyramids at the Oasis ─ Wendy Moore ____________________________________________ 3 2 - Day Classes: Saturday, March 19 through Sunday, March 20______________________________ 3 101: Discovering Value ─ Do Andrew __________________________________________________ 3 102: Starry Night Kimono ─ Toni Gerdes _______________________________________________ 4 103: Pom Pom Shoes ─ Deborah Mitek ________________________________________________ 4 104: Secret Window ─ Kurdy Biggs ___________________________________________________ 5 105: Felted Beech Tree ─ Laura Smith _________________________________________________ 5 106: Crewel Necessities ─ Kim Sanders ________________________________________________ 6 107: Studio time with Dawn Donnelly _________________________________________________ 6 2 - Day Classes: Monday, March 21 through Tuesday, March 22 _____________________________ 7 201: Casting Spells ─ Dawn Donnelly __________________________________________________ 7 202: Pumpkin Patch ─ Jennifer Riefenberg _____________________________________________ 7 203: Poppies in a Copper Bowl – Gail Sirna _____________________________________________