Blacklisted: the Unwarranted Divestment of Access to Bank Accounts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Venture Debt Determining When It’S the Right Path for Your Business

INSIGHTS | Legal Affairs Venture debt Determining when it’s the right path for your business INTERVIEWED BY SUE OSTROWSKI or startup companies lacking the Michael E. Fink cash flow or liquid assets to obtain a Attorney traditional bank loan, venture debt Babst Calland Fcould be the answer to help elevate them 412.394.6477 FOLLOW UP: To learn about venture debt or other to the next level. [email protected] financing alternatives, contact attorneys in our “Startups often lack many of the Emerging Technologies Group. characteristics that would give traditional lenders comfort that a regular INSIGHTS Legal Affairs is brought to you by Babst Calland commercial loan would be a good deal for them,” says Michael Fink, attorney the lender may receive a warrant to HOW CAN A BUSINESS DETERMINE at Babst Calland. “Venture debt can be purchase either common equity or the IF VENTURE DEBT IS THE RIGHT an alternative to help bridge the gap to a preferred equity to be issued in the next PATH? company’s next valuation.” fundraising round, typically at a discount. Just because you can go out and get Smart Business spoke with Michael money doesn’t mean you should. There about how taking on venture debt can WHEN SHOULD A COMPANY should be a solid reason for taking on keep a business moving forward without CONSIDER PURSUING VENTURE venture debt or any other investment. decreasing its valuation. DEBT? It’s really dependent on the Venture debt typically isn’t available circumstances of the business. As with WHAT IS VENTURE DEBT, AND HOW until a company has had a priced equity any financing deal, venture debt can IS IT STRUCTURED? fundraising round that includes a get complicated very quickly, and an At its core, venture debt looks similar to valuation for the lender to work from. -

New Credit Do You Know How to Play Your Cards Right?

New credit Do you know how to play your cards right? In most card games, someone invites you to join in, and you are dealt a hand. What you do with those cards is up to you. Play them wisely, and you may win. Make bad decisions, and you could lose. The credit game is much the same, with one very important difference: You are the only person in the game. If you manage your credit well, you can’t lose. Getting in on the credit game The most important rule is to pay your bills on time. Playing the credit game well gives you the added flexibility If you observe that one simple rule, you will succeed and security of credit at your disposal. You can improve at the credit game. your lifestyle through purchases that are possible only with credit and utilize services that are easily available only The playing cards of credit if you have a credit card — renting a car, for example. You In a deck of cards, there are four suits: hearts, diamonds, have the resources to pay for unexpected emergencies. clubs and spades. Credit can be similarly divided. Here are the kinds of credit you can use: But there are risks. Poorly managed credit can drive Revolving credit: Most credit cards are a form of revolving you deep into debt. Getting back in the game isn’t easy, credit. This simply means you are given a maximum credit but with time and self-control, you can regain control and limit, and you can make charges against that limit, carrying get a fresh start. -

And More Lenders Are Offering Home Equity Lines of Credit. by Using The

taking a percentage (say, 75 percent) of the home's appraised value and subtracting from that the balance What should you look for when shopping for a plan? owed on the existing mortgage. For example, If you decide to apply for a home equity line of credit, look for the plan that best meets your particular needs. Read the credit agreement carefully, and examine the terms and conditions of various plans, including the annual percentage rate (APR) and the costs of establishing the plan. The APR for a home equity line is based on the interest rate alone and will not reflect the closing costs and other fees and charges, so you'll need to compare these costs, as well as the APRs, among lenders. Interest rate charges and related plan features Home equity lines of credit typically involve variable rather than fixed interest rates. The variable rate must be based on a publicly available index (such as the prime rate published in some major daily newspapers or a U.S. Treasury bill rate); the interest rate for borrowing under the home equity line changes, mirroring fluctuations in More and more lenders are offering home equity lines of [D] the value of the index. Most lenders cite the interest rate credit. By using the equity in your home, you may qualify In determining your actual credit limit, the lender will also you will pay as the value of the index at a particular time for a sizable amount of credit, available for use when and consider your ability to repay, by looking at your income, plus a "margin," such as 2 percentage points. -

Rules and Regulations Federal Register Vol

35003 Rules and Regulations Federal Register Vol. 84, No. 140 Monday, July 22, 2019 This section of the FEDERAL REGISTER Division, STOP 0784, Room 2250, provisions of Title II of the UMRA) for contains regulatory documents having general USDA Rural Development, South State, local, and tribal governments or applicability and legal effect, most of which Agriculture Building, 1400 the private sector. Therefore, this rule is are keyed to and codified in the Code of Independence Avenue SW, Washington, not subject to the requirements of Federal Regulations, which is published under DC 20250–0784, telephone: (503) 894– sections 202 and 205 of the UMRA. 50 titles pursuant to 44 U.S.C. 1510. 2382, email is [email protected]. Environmental Impact Statement The Code of Federal Regulations is sold by SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: the Superintendent of Documents. This document has been reviewed in Executive Order 12866, Classification accordance with 7 CFR part 1970, This rule has been determined to be subpart A, ‘‘Environmental Programs.’’ DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE non-significant and therefore was not It is the determination of the Agency reviewed by the Office of Management that this action does not constitute a Rural Housing Service and Budget (OMB) under Executive major Federal action significantly Order 12866. affecting the quality of the human 7 CFR Part 3555 environment, and, in accordance with Executive Order 12988, Civil Justice RIN 0575–AD10 the National Environmental Policy Act Reform of 1969, Public Law 91–190, neither an Single Family Housing Guaranteed This final rule has been reviewed Environmental Assessment nor an Loan Program under Executive Order 12988, Civil Environmental Impact Statement is Justice Reform. -

QFI PM Model Solutions Spring 2021

QFI PM Model Solutions Spring 2021 1. Learning Objectives: 2. The candidate will understand: • The credit risk of fixed income portfolios, securities, and sectors and be able to apply a variety of credit risk theories and models. • How rating agencies rate corporate and sovereign bonds. Learning Outcomes: (2a) Demonstrate an understanding of credit risk analysis and models (2f) Understand and apply various approaches for managing credit risk in a portfolio setting Sources: 1. Maginn & Tuttle, Managing Investment Portfolios, 3rd Edition, Chapter 7, p. 410. 2. Maginn & Tuttle, Managing Investment Portfolios, 3rd Edition, Chapter 7, p. 432- 433. 3. Maginn & Tuttle, Managing Investment Portfolios, 3rd Edition, Chapter 7, p. 414- 415. 4. Maginn & Tuttle, Managing Investment Portfolios, 3rd Edition, Chapter 7, p. 425- 427. 5. Maginn & Tuttle, Managing Investment Portfolios, 3rd Edition, Chapter 7, p. 452- 454. Commentary on Question: Commentary listed underneath question component. Solution: (a) Define passive, active, and semi-active equity investing. Commentary on Question: The candidates performed very well on this section. They demonstrated an understanding of the basic concepts surrounding passive, active, and semi-active investing that was in line with the level expected. -Passive: The investor is not expressing his investment expectations through changes in security holdings. -Active: Investor seeks to outperform a benchmark portfolio by identifying stocks that will perform well and avoiding stocks that will underperform -Semi-active: Investor seeks to outperform the benchmark but is mindful of tracking risk relative to the benchmark QFI PM Spring 2021 Solutions Page 1 1. Continued (b) Calculate the weighting of XYZ under each of the following index weighting methods: (i) Price-weighted (ii) Equal-weighted (iii) Float-weighted Commentary on Question: The candidates performed very well on this section. -

Chapter 9: Income Analysis 7 Cfr 3555.152

HB-1-3555 CHAPTER 9: INCOME ANALYSIS 7 CFR 3555.152 9.1 INTRODUCTION The lender is responsible to confirm applicants and households meet eligibility criteria for the Single Family Housing Guaranteed Loan Program (SFHGLP). Lenders must calculate and document annual, adjusted, and repayment income. The guidance provided applies to both manually underwritten loans and loans that utilize the Agency’s automated underwriting system, GUS. SECTION 1: ELIGIBILITY INCOME 9.2 OVERVIEW The SFHGLP assists very-low, low, and moderate-income households. Therefore, the lender must certify that any household that requests a loan guarantee does not exceed the adjusted annual income threshold for the applicable state and county where the dwelling is located. The Agency provides income eligibility information in Appendix 5 of this Handbook to lenders and updates the limits as they are revised. This section assists lenders to analyze income types, complete income calculations (annual, adjusted, and repayment), and document the income with acceptable verifications. Documentation of income calculations should be provided on Attachment 9-B, or the Uniform Transmittal Summary, (FNMA FORM 1008/FREDDIE MAC FORM 1077), or equivalent. Attachment 9-C provides a case study to illustrate how to properly complete the income worksheet. A public website is available to assist in the calculation of annual and adjusted annual income at: http://eligibility.sc.egov.usda.gov/eligibility/. 9.3 ANNUAL INCOME [7 CFR 3555.152(B)] Annual income will include all eligible income sources from all adult household members, not just parties to the loan note. The annual income for the household will be used to calculate the adjusted annual household income. -

Should Your Nonprofit Get a Bank Loan Or Line of Credit?

Should Your Nonprofit Get a Bank Loan or Line of Credit? It’s a tough time for many, and nonprofits organizations are no exception. Even nonprofits that have been around for decades are struggling right now with so many new challenges and an uncertain future. Nonprofits are often able to predict and plan out their yearly cash inflows based on past history but throw in a pandemic, a recession, and political uncertainty and it is hard to know if your cash forecasting will be accurate, it’s probably likely to be your least accurate forecast yet. Many nonprofits never considered a loan or a line of credit from a bank but now might be the time to consider that option based on a few important factors. Let’s discuss what a loan or line of credit might do for you, what you would need to be approved, and what loan options your nonprofit might have. A Loan or a Line of Credit Buys You Time Many nonprofits that have been around for a long time have had to weather many storms. Businesses have used financing in times of crisis to help them get through those uncertain periods, but nonprofits often have been reluctant to use this important tool. First, what is the Difference Between a Term Loan and a Line of Credit? There are two categories of loans a nonprofit might want to consider, depending on their circumstances. A term loan and a line of credit. Term Loan A term loan is a fixed amount of money that is paid back monthly over a few years. -

What You Should Know About Home Equity Lines of Credit

What You Should Know About Home Equity Lines of Credit Consumer Finance Protection Bureau Lender Name: Address: This booklet was initially prepared by the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) has made technical updates to the booklet to reflect new mortgage rules under Title XIV of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (Dodd-Frank Act). A larger update of this booklet is planned in the future to reflect other changes under the Dodd-Frank Act and to align with other CFPB resources and tools for consumers as part of the CFPB's broader mission to educate consumers. Consumers are encouraged to visit the CPFB's website at consumerfinance.gov/owning-a-home to access interactive tools and resources for mortgage shoppers, which are expected to be available beginning in 2014. Table of contents Table of contents 1 1. Introduction 2 1.1 Home equity plan checklist 2 2. What is a home equity line of credit? 3 2.1 What should you look for when shopping for a plan? 4 2.2 Costs of establishing and maintaining a home equity line 4 2.3 How will you repay your home equity plan? 4 2.4 Line of credit vs. traditional second mortgage loans 5 2.5 What if the lender freezes or reduces your line of credit? 6 Appendix A: 6 Defined terms 6 Appendix B: 8 More information 8 Appendix C: 8 Contact information 8 What You Should Know About Home Equity Lines of Credit CFPB January 2014 Bankers Systems VMP VMP483 (1401).02 Wolters Kluwer Financial Services Page 1 of 10 1. -

13 CFR Ch. I (1–1–15 Edition)

§ 107.550 13 CFR Ch. I (1–1–15 Edition) insured amount, but only if the institu- have outstanding Leverage and you tion is ‘‘well capitalized’’ in accordance have a secured line of credit that was with the definition set forth in regula- created on or before April 8, 1994, you tions of the Federal Deposit Insurance must receive SBA’s written approval of Corporation, as amended (12 CFR the line before you increase the 325.103). amounts outstanding thereunder. (2) Exception: You may make a tem- (d) Conditions for SBA approval. As a porary deposit (not to exceed 30 days) condition of granting its approval in excess of the insured amount, in a under this § 107.550, SBA may impose transfer account established to facili- such restrictions or limitations as it tate the receipt and disbursement of deems appropriate, taking into account funds or to hold funds necessary to your historical performance, current honor Commitments issued. financial position, proposed terms of (d) Deposit of funds in Associate insti- the secured debt and amount of aggre- tution. A deposit in, or a repurchase gate debt you will have outstanding agreement with, a federally insured in- (including Leverage). SBA will not fa- stitution that is your Associate is not vorably consider any requests for ap- considered a Financing of such Asso- proval which include a blanket lien on ciate under § 107.730, provided the terms all your assets, or a security interest of such deposit or repurchase agree- in your investor commitments in ex- ment are no less favorable than those cess of 125 percent of the proposed bor- available to the general public. -

Joint AFME – ISDA Response to the European Commission's

Joint AFME – ISDA Response to the European Commission’s Consultation on CRR3 Implementation December 2019 Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................................... 4 Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................................................ 4 Trade Association Contacts .................................................................................. Error! Bookmark not defined. 1. Credit risk............................................................................................................................................................................. 12 1.1 Standardised Approach (SA-CR) ......................................................................................................................... 12 1.2 Internal Ratings Based Approaches (IRBA) ................................................................................................... 35 1.3 Credit Risk Mitigation – SA-CR ............................................................................................................................ 50 1.4 Credit Risk Mitigation – IRBA ............................................................................................................................... 53 2. Securities financing transactions (SFTs)................................................................................................................ -

Line-Of-Credit Predisclosure (Interest Only) License Number

2807 S. State Street St. Joseph, MI 49085 (888) 982-1400 Line-of-Credit Predisclosure (Interest Only) License Number IMPORTANT TERMS OF OUR HOME EQUITY LINE OF CREDIT This disclosure contains important information about your Home Equity Open-End Credit Plan. You should read it carefully and keep a copy for your records. Availability of Terms: All of the terms described below are subject to change. If any of these terms change (other than the ANNUAL PERCENTAGE RATE) and you decide, as a result, not to enter into an agreement with us, you are entitled to a refund of any fees that you paid to us or anyone else in connection with your application. Security Interest: We will take a Security Interest on your home. You could lose your home if you do not meet the obligations in your agreement with us. Possible Actions: Termination and Acceleration For Wisconsin Borrowers Only: We can terminate the Home Equity Open-end Credit Plan and require you to pay us the entire outstanding balance in one payment and charge you certain fees if: (a) you fail to make a required payment when due two times within a twelve month period, or (b) your failure to observe the terms of this Plan materially impairs the condition, value, or protection of, or our rights in, the property securing this Plan For All Other Borrowers: We can terminate the Home Equity Open-end Credit Plan and require you to pay us the entire outstanding balance in one payment and charge you certain fees if: (a) you commit fraud or material misrepresentation at any time in connection with this Plan; (b) you do not meet the repayment terms of this Plan; (c) your action or inaction adversely affects the collateral for the Plan or our rights in the collateral. -

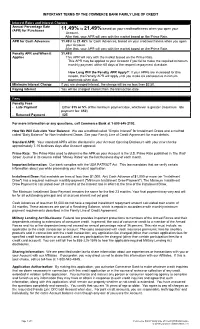

(APR) for Purchases 11.49% 21.49% Account

IMPORTANT TERMS OF THE COMMERCE BANK FAMILY LINE OF CREDIT Interest Rates and Interest Charges Annual Percentage Rate to based on your creditworthiness when you open your (APR) for Purchases 11.49% 21.49% Account. After that, your APR will vary with the market based on the Prime Rate. APR for Cash Advances 11.49% to 21.49% for Cash Advances, based on your creditworthiness when you open your Account. After that, your APR will vary with the market based on the Prime Rate. Penalty APR and When it 31.49% Applies This APR will vary with the market based on the Prime Rate. This APR may be applied to your Account if you fail to make the required minimum monthly payment within 60 days of the respective payment due date. How Long Will the Penalty APR Apply?: If your APRs are increased for this reason, the Penalty APR will apply until you make six consecutive minimum payments when due. Minimum Interest Charge If you are charged interest, the charge will be no less than $2.50. Paying Interest You will be charged Interest from the transaction date. Fees Penalty Fees - Late Payment Either $15 or 5% of the minimum payment due, whichever is greater (maximum late payment fee: $50) - Returned Payment $25 For more information or any questions, call Commerce Bank at 1-800-645-2103. How We Will Calculate Your Balance: We use a method called “Simple Interest” for Installment Draws and a method called “Daily Balance” for Non-Installment Draws. See your Family Line of Credit Agreement for more details.