Freak, Out! : Disability Representation in Theatre

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stage by Stage South Bank: 1988 – 1996

Stage by Stage South Bank: 1988 – 1996 Stage by Stage The Development of the National Theatre from 1848 Designed by Michael Mayhew Compiled by Lyn Haill & Stephen Wood With thanks to Richard Mangan and The Mander & Mitchenson Theatre Collection, Monica Sollash and The Theatre Museum The majority of the photographs in the exhibition were commissioned by the National Theatre and are part of its archive The exhibition was funded by The Royal National Theatre Foundation Richard Eyre. Photograph by John Haynes. 1988 To mark the company’s 25th birthday in Peter Hall’s last year as Director of the National October, The Queen approves the title ‘Royal’ Theatre. He stages three late Shakespeare for the National Theatre, and attends an plays (The Tempest, The Winter’s Tale, and anniversary gala in the Olivier. Cymbeline) in the Cottesloe then in the Olivier, and leaves to start his own company in the The funds raised are to set up a National West End. Theatre Endowment Fund. Lord Rayne retires as Chairman of the Board and is succeeded ‘This building in solid concrete will be here by the Lady Soames, daughter of Winston for ever and ever, whatever successive Churchill. governments can do to muck it up. The place exists as a necessary part of the cultural scene Prince Charles, in a TV documentary on of this country.’ Peter Hall architecture, describes the National as ‘a way of building a nuclear power station in the September: Richard Eyre takes over as Director middle of London without anyone objecting’. of the National. 1989 Alan Bennett’s Single Spies, consisting of two A series of co-productions with regional short plays, contains the first representation on companies begins with Tony Harrison’s version the British stage of a living monarch, in a scene of Molière’s The Misanthrope, presented with in which Sir Anthony Blunt has a discussion Bristol Old Vic and directed by its artistic with ‘HMQ’. -

King and Country: Shakespeare’S Great Cycle of Kings Richard II • Henry IV Part I Henry IV Part II • Henry V Royal Shakespeare Company

2016 BAM Winter/Spring #KingandCountry Brooklyn Academy of Music Alan H. Fishman, Chairman of the Board William I. Campbell, Vice Chairman of the Board BAM, the Royal Shakespeare Company, and Adam E. Max, Vice Chairman of the Board The Ohio State University present Katy Clark, President Joseph V. Melillo, Executive Producer King and Country: Shakespeare’s Great Cycle of Kings Richard II • Henry IV Part I Henry IV Part II • Henry V Royal Shakespeare Company BAM Harvey Theater Mar 24—May 1 Season Sponsor: Directed by Gregory Doran Set design by Stephen Brimson Lewis Global Tour Premier Partner Lighting design by Tim Mitchell Music by Paul Englishby Leadership support for King and Country Sound design by Martin Slavin provided by the Jerome L. Greene Foundation. Movement by Michael Ashcroft Fights by Terry King Major support for Henry V provided by Mark Pigott KBE. Major support provided by Alan Jones & Ashley Garrett; Frederick Iseman; Katheryn C. Patterson & Thomas L. Kempner Jr.; and Jewish Communal Fund. Additional support provided by Mercedes T. Bass; and Robert & Teresa Lindsay. #KingandCountry Royal Shakespeare Company King and Country: Shakespeare’s Great Cycle of Kings BAM Harvey Theater RICHARD II—Mar 24, Apr 1, 5, 8, 12, 14, 19, 26 & 29 at 7:30pm; Apr 17 at 3pm HENRY IV PART I—Mar 26, Apr 6, 15 & 20 at 7:30pm; Apr 2, 9, 23, 27 & 30 at 2pm HENRY IV PART II—Mar 28, Apr 2, 7, 9, 21, 23, 27 & 30 at 7:30pm; Apr 16 at 2pm HENRY V—Mar 31, Apr 13, 16, 22 & 28 at 7:30pm; Apr 3, 10, 24 & May 1 at 3pm ADDITIONAL CREATIVE TEAM Company Voice -

Shakespeare's Great Cycle of Kings / Brooklyn Academy of Music Elizabeth Zeman Kolkovich

Early Modern Culture Volume 12 Article 24 6-12-2017 King and Country: Shakespeare's Great Cycle of Kings / Brooklyn Academy of Music Elizabeth Zeman Kolkovich Joey Burley Kaylor Montgomery Will Sly Ashley Van Hesteren Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/emc Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons, and the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Elizabeth Zeman Kolkovich, Joey Burley, Kaylor Montgomery, Will Sly, and Ashley Van Hesteren (2017) "King and Country: Shakespeare's Great Cycle of Kings / Brooklyn Academy of Music," Early Modern Culture: Vol. 12 , Article 24. Available at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/emc/vol12/iss1/24 This Theater Review is brought to you for free and open access by TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in Early Modern Culture by an authorized editor of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. King and Country: Shakespeare’s Great Cycle of Kings Harvey Theater, Brooklyn Academy of Music (BAM) Brooklyn, New York Performance Dates: April 8-10, 2016 Reviewed by ELIZABETH ZEMAN KOLKOVICH with JOEY BURLEY, KAYLOR MONTGOMERY, WILL SLY, and ASHLEY VAN HESTEREN he Royal Shakespeare Company’s “King and Country: Shakespeare’s Great Cycle of Kings,” directed by Gregory Doran, performed full-length versions of Richard T II, 1 Henry IV, 2 Henry IV, and Henry V in succession. These plays originated as individual performances at Stratford-upon-Avon in 2013-15 and then toured as a cycle to London, China, Hong Kong, and New York. We saw the New York version: a whirlwind tour through four plays in three days at the Brooklyn Academy of Music.1 The production merged Shakespeare’s time with our own in its costuming and effects. -

Press Release

Press Release Unique collaboration with RSC to mark 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death Shakespeare in Art: Tempests, Tyrants and Tragedy 19 March ‐ 19 June 2016 Compton Verney, Warwickshire Already hailed as one of 2016’s must‐see exhibitions, Shakespeare in Art: Tempests, Tyrants and Tragedy is a landmark collaboration with the Royal Shakespeare Company commemorating the 400th anniversary of the bard’s death. A master of dramatising human emotions in their myriad forms, Shakespeare’s plays have in turn inspired countless artists. Shakespeare in Art: Tempests, Tyrants and Tragedy will focus on those pivotal Shakespeare plays which have motivated artists across the ages – from Sargent, Fuseli, Rossetti, Blake, Watts and Romney to Karl Weschke, Kate Tempest and Tom Hunter – exploring the enduring appeal of the Elizabethan playwright. This exhibition offers an exceptional opportunity for both art and theatre lovers to reimagine Shakespeare’s works through a unique series of multi‐media, multi‐sensory encounters; including painting, photography, projection, sound and light. Using specially commissioned audio drawing on excerpts from Shakespeare's plays, leading RSC actors will bring to life scenes from some of the major paintings. Uniquely for an art gallery, the exhibition will be designed by the Royal Shakespeare Company’s Director of Design, Stephen Brimson Lewis. Over seventy works – including paintings, drawings, engravings, woodcuts and photos – have been sourced from across the UK for this remarkable show, taking place just nine miles away from Shakespeare’s birthplace, Stratford‐upon‐Avon. Works will travel to Compton Verney from Bolton, Birmingham, Edinburgh and York, plus Tate and the V&A in London and the show will also include a number of key works from the RSCS’s own, rarely publicly displayed art collection. -

“I Will Never Play the Dane”: Shakespeare and the Performer's Failure

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by MURAL - Maynooth University Research Archive Library DOI: 10.1111/lic3.12470 ARTICLE “I will never play the Dane”: Shakespeare and the performer's failure Richard O'Brien University of Birmingham Abstract Correspondence Richard O'Brien, Department of Film and The cultural prestige accorded to Shakespeare's great roles Creative Writing, University of Birmingham, has made them high watermarks for ‘great acting’ in general. Birmingham, UK. Email: [email protected] They are therefore also uniquely capable of channelling a performer's sense of his own failure. The 1987 film Withnail &Ifamously ends with its title character, an out‐of‐work actor and self‐destructive alcoholic, delivering Hamlet's “What a piece of work is a man” to an audience of unre- sponsive wolves. And in 2014's The Trip to Italy, Steve Coogan plays a fictionalised version of himself: a comedian who fears he will never be remembered as a serious artist. On a visit to Pompeii, Coogan's delivery of Hamlet's speech to Yorick's skull similarly becomes a way of channelling the series's wider reflections on fame, mortality, and the value of the actor's art. Drawing on Marvin Carlson's argument that the role of Hamlet is unusually densely ghosted by its previous occupants, this article will explore how these two contemporary depictions of struggling performers evoke the received idea of the great Shakespearean role as the pinnacle of the actor's art to respond to the dilemma of how to cope with creative failure. -

P E R F O R M I N G

PERFORMING & Entertainment 2019 BOOK CATALOG Including Rowman & Littlefield and Imprints of Globe Pequot CONTENTS Performing Arts & Entertainment Catalog 2019 FILM & THEATER 1 1 Featured Titles 13 Biography 28 Reference 52 Drama 76 History & Criticism 82 General MUSIC 92 92 Featured Titles 106 Biography 124 History & Criticism 132 General 174 Order Form How to Order (Inside Back Cover) Film and Theater / FEATURED TITLES FORTHCOMING ACTION ACTION A Primer on Playing Action for Actors By Hugh O’Gorman ACTION ACTION Acting Is Action addresses one of the essential components of acting, Playing Action. The book is divided into two parts: A Primer on Playing Action for Actors “Context” and “Practice.” The Context section provides a thorough examination of the theory behind the core elements of Playing Action. The Practice section provides a step-by-step rehearsal guide for actors to integrate Playing Action into their By Hugh O’Gorman preparation process. Acting Is Action is a place to begin for actors: a foundation, a ground plan for how to get started and how to build the core of a performance. More precisely, it provides a practical guide for actors, directors, and teachers in the technique of Playing Action, and it addresses a niche void in the world of actor training by illuminating what exactly to do in the moment-to-moment act of the acting task. March, 2020 • Art/Performance • 184 pages • 6 x 9 • CQ: TK • 978-1-4950-9749-2 • $24.95 • Paper APPLAUSE NEW BOLLYWOOD FAQ All That’s Left to Know About the Greatest Film Story Never Told By Piyush Roy Bollywood FAQ provides a thrilling, entertaining, and intellectually stimulating joy ride into the vibrant, colorful, and multi- emotional universe of the world’s most prolific (over 30 000 film titles) and most-watched film industry (at 3 billion-plus ticket sales). -

Henry IV, Part I

High sparks of honor in thee have I seen. Thank You - Richard II Season 2018-2019 is presented by Additional Sponsors and Funders Include This production has been funded by Mayor Catherine E. Pugh and the Baltimore Office of Promotion and The Arts The Citizens of Baltimore County William G. Baker, Jr. Memorial Fund Mayor Catherine E. Pugh & the City of Baltimore Creator of the Baker Artist Portfolios | www.Bakerartist.org Community Partners and Media Partners Education Partners and Acknowledgments Morgan State University High Point University Vet Arts Connect Institute for Integrative Health Creative Forces®: NEA Military Healing Arts Network 2 HENRY IV, PARTS I AND II Shakespeare’s Innovative Storytelling A Note from CSC's Founder and Artistic Director Congratulations! You didn’t let all the Roman numerals keep you away from these great plays. People can be scared once Shakespeare play titles start including “Part I,” etc. That’s a shame, particularly with Henry IV, Parts I and II. These are two terrifi c plays. Ian Gallanar Of course, these are the plays that introduced Falstaff to the world. That would seem like enough of an accomplishment. Falstaff is one of the most beloved (and imitated) characters in the history of the theater (and movies). Shakespeare wrote three plays featuring Falstaff (The Merry Wives of Windsor in addition to the two Henry IV plays) and mentions him in a fourth play (Henry V). Falstaff also appears in other theatrical works – Falstaff ’s Wedding by William Kenrick, at least seven operas, and many novels. But that’s not all the Henry IV plays have to off er. -

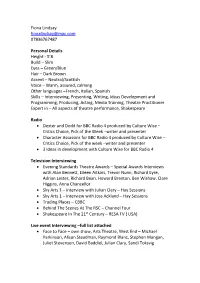

Fiona Lindsay [email protected] 07836767487

Fiona Lindsay [email protected] 07836767487 Personal Details Height - 5’8 Build – Slim Eyes – Green/Blue Hair – Dark Brown Accent – Neutral/Scottish Voice – Warm, assured, calming Other languages –French, Italian, Spanish Skills – Interviewing, Presenting, Writing, Ideas Development and Programming, Producing, Acting, Media Training, Theatre Practitioner Expert in – All aspects of theatre performance, Shakespeare Radio Dexter and Dodd for BBC Radio 4 produced by Culture Wise – Critics Choice, Pick of the Week –writer and presenter Character Assassins for BBC Radio 4 produced by Culture Wise – Critics Choice, Pick of the week –writer and presenter 3 Ideas in development with Culture Wise for BBC Radio 4 Television Interviewing Evening Standards Theatre Awards – Special Awards Interviews with Alan Bennett, Eileen Aitkins, Trevor Nunn, Richard Eyre, Adrian Lester, Richard Bean, Howard Brenton, Ben Wishaw, Clare Higgins, Anna Chancellor Sky Arts 1 – Interview with Julian Clary – Hay Sessions Sky Arts 1 – Interview with Joss Ackland – Hay Sessions Trading Places – CBBC Behind The Scenes At The RSC – Channel Four Shakespeare In The 21st Century – RESA TV ( USA) Live event Interviewing –full list attached Face to Face – own show, Arts Theatre, West End – Michael Parkinson, Alison Steadman, Raymond Blanc, Stephen Mangan, Juliet Stevenson, David Baddiel, Julian Clary, Sandi Toksvig Cheltenham Literature Festival – recent interviews include – Rupert Everett, Ken Dodd, Paul O’Grady, Patricia Hodge, Sandi Toksvig, Ben Fogle, Stephen -

LATE 20Th and EARLY 21St CENTURY CLOWNING's

CLOWNING ON AND THROUGH SHAKEPEARE: LATE 20th AND EARLY 21st CENTURY CLOWNING’S TACTICAL USE IN SHAKESPEARE PERFORMANCE by David W Peterson BA, University of Michigan, 2007 Masters, Michigan State University, 2009 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2014 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH THE KENNETH P. DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by David W Peterson It was defended on April 16, 2014 and approved by Dr. Attilio “Buck” Favorini, Professor Emeritus, Theatre Arts Dr. Bruce McConachie, Professor, Theatre Arts Dr. Jennifer Waldron, Associate Professor, English Dissertation Advisor: Dr. Lisa Jackson-Schebetta, Assistant Professor, Theatre Arts ii Copyright © by David Peterson 2014 iii CLOWNING ON AND THROUGH SHAKEPEARE: LATE 20th AND EARLY 21st CENTURY CLOWNING’S TACTICAL USE IN SHAKESPEARE PERFORMANCE David Peterson, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2014 This dissertation argues that contemporary clown performance (as developed in the latter half of the 20th century) can be understood in terms of three key performance practices: the flop, interruption, and audience play. I further argue that these three features of flop, interruption, and audience play are distinctively facilitated by Shakespeare in both text and performance which, in turn, demonstrates the potential of both clown and Shakespeare to not only disrupt theatrical conventions, but to imagine new relationships to social and political power structures. To this end, I ally the flop with Jack Halberstam’s sense of queer failure to investigate the relationship between Macbeth and 500 Clown Macbeth. -

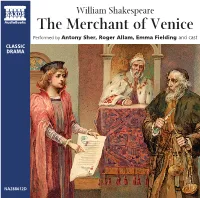

The Merchant of Venice Performed by Antony Sher, Roger Allam, Emma Fielding and Cast CLASSIC DRAMA

William Shakespeare The Merchant of Venice Performed by Antony Sher, Roger Allam, Emma Fielding and cast CLASSIC DRAMA NA288612D 1 Act 1 Scene 1: In sooth, I know not why I am so sad: 9:55 2 Act 1 Scene 2: By my troth, Nerissa, my little body is aweary… 7:20 3 Act 1 Scene 3: Three thousand ducats; well. 6:08 4 Signior Antonio, many a time and oft… 4:06 5 Act 2 Scene 1: Mislike me not for my complexion… 2:26 6 Act 2 Scene 2: Certainly my conscience… 4:21 7 Nay, indeed, if you had your eyes, you might fail of… 4:19 8 Father, in. I cannot get a service, no; 2:49 9 Act 2 Scene 3: Launcelot I am sorry thou wilt leave my father so: 1:15 10 Act 2 Scene 4: Nay, we will slink away in supper-time, 1:50 11 Act 2 Scene 5: Well Launcelot, thou shalt see, 3:16 12 Act 2 Scene 6: This is the pent-house under which Lorenzo… 1:32 13 Here, catch this casket; it is worth the pains. 1:49 14 Act 2 Scene 7: Go draw aside the curtains and discover… 5:04 15 O hell! what have we here? 1:23 16 Act 2 Scene 8: Why, man, I saw Bassanio under sail: 2:27 17 Act 2 Scene 9: Quick, quick, I pray thee; draw the curtain straight: 6:48 2 18 Act 3 Scene 1: Now, what news on the Rialto Salerino? 2:13 19 To bait fish withal: 5:17 20 Act 3 Scene 2: I pray you, tarry: pause a day or two… 4:39 21 Tell me where is fancy bred… 6:52 22 You see me, Lord Bassanio, where I stand… 9:56 23 Act 3 Scene 3: Gaoler, look to him: tell not of Mercy… 2:05 24 Act 3 Scene 4: Portia, although I speak it in your presence… 3:56 25 Act 3 Scene 5: Yes, truly; for, look you the sins of the father… 4:28 26 Act 4 Scene 1: What, is Antonio here? 4:42 27 What judgment shall I dread, doing. -

SHAKESPEARE in PERFORMANCE Some Screen Productions

SHAKESPEARE IN PERFORMANCE some screen productions PLAY date production DIRECTOR CAST company As You 2006 BBC Films / Kenneth Branagh Rosalind: Bryce Dallas Howard Like It HBO Films Celia: Romola Gerai Orlando: David Oyelewo Jaques: Kevin Kline Hamlet 1948 Two Cities Laurence Olivier Hamlet: Laurence Olivier 1980 BBC TVI Rodney Bennett Hamlet: Derek Jacobi Time-Life 1991 Warner Franco ~effirelli Hamlet: Mel Gibson 1997 Renaissance Kenneth Branagh Hamlet: Kenneth Branagh 2000 Miramax Michael Almereyda Hamlet: Ethan Hawke 1965 Alpine Films, Orson Welles Falstaff: Orson Welles Intemacional Henry IV: John Gielgud Chimes at Films Hal: Keith Baxter Midni~ht Doll Tearsheet: Jeanne Moreau Henry V 1944 Two Cities Laurence Olivier Henry: Laurence Olivier Chorus: Leslie Banks 1989 Renaissance Kenneth Branagh Henry: Kenneth Branagh Films Chorus: Derek Jacobi Julius 1953 MGM Joseph L Caesar: Louis Calhern Caesar Manluewicz Brutus: James Mason Antony: Marlon Brando ~assiis:John Gielgud 1978 BBC TV I Herbert Wise Caesar: Charles Gray Time-Life Brutus: kchard ~asco Antony: Keith Michell Cassius: David Collings King Lear 1971 Filmways I Peter Brook Lear: Paul Scofield AtheneILatenla Love's 2000 Miramax Kenneth Branagh Berowne: Kenneth Branagh Labour's and others Lost Macbeth 1948 Republic Orson Welles Macbeth: Orson Welles Lady Macbeth: Jeanette Nolan 1971 Playboy / Roman Polanslu Macbe th: Jon Finch Columbia Lady Macbeth: Francesca Annis 1998 Granada TV 1 Michael Bogdanov Macbeth: Sean Pertwee Channel 4 TV Lady Macbeth: Greta Scacchi 2000 RSC/ Gregory -

The Macbeth Project (Review) Todd Landon Barnes

MacB: The Macbeth Project (review) Todd Landon Barnes Shakespeare Bulletin, Volume 27, Number 3, Fall 2009, pp. 462-468 (Review) Published by Johns Hopkins University Press DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/shb.0.0102 For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/316797 [ Access provided at 30 Sep 2021 00:09 GMT with no institutional affiliation ] 462 SHAKESPEARE BULLETIN Ray was a teacher? Was it Newsome’s voice? Atllas’s? Another collabora- tor’s? When asked, Atllas said that the epilogue was part of the script as he received it. Regardless of how the epilogue came into being, its effect perfectly reiterated that of the production as a whole: powerfully drawing attention to the reciprocal relationship between lived experience and the expression of this experience through various hip-hop idioms. n MacB: The Macbeth Project Presented by The African-American Shakespeare Company at the Buriel Clay Theatre, San Francisco, California. September 19–October 5, 2008 and Willow High School, Crockett, California. March 9–March 20, 2009. Directed and adapted by Victoria Evans Erville. Lighting designed by Kevin Myrick. Set designed by Atom Gray. Costumes designed by Steven Lamont. Choreography by LaTonya Watts. Fights directed by Dave Maier. Music by Dogwood Speaks and Johnathan Williams. Teaching by Sherri Young. With David Moore (Macbeth), Melvina Jones (Lady Macbeth, Melody), Johnathan Williams (Banquo, Hipcat, Macduff ), Maikiko James (Witch 1, Old Man, Ensemble), DC Allen (Witch 2, Porter, Ensemble), Toya Willock (Witch 3, Lenox, Ensemble), Clifton Jones (Duncan, Ross), Levertis Stall- ings (Fleance), and others. Todd Landon Barnes, University of California, Berkeley San Francisco’s African-American Shakespeare Company recently finished staging its second hip-hopMacbeth .