THESE ARTISTS GIVE NEW MEANING to TOOLS of the TRADE St

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Portraiture: People & Places in Time Teaching Resource

Portraiture: People & Places in Time Teaching Resource Ages: 8+ (Grades 3–12) Essential Questions: • What is a portrait? What is a self-portrait? Materials needed: • What are some traditional portraiture • Paper techniques? What are some of the • Pencil, marker, crayon, or pen different artistic mediums that can be • Access to a mirror used to create portraits? • Ruler (optional) • How does an artist use colors and shapes • Materials for adding color to portrait when building a portrait? scenes (optional) • How does an artist use stance and expression to communicate a specific Duration: 1 hour (includes one 15-minute emotion or emotions in a work of activity and two 20-minute activities) portraiture? • What can a portrait of a person or group of people tell us about a specific time and place? Image: John White Alexander (American, 1856–1915). Azalea (Portrait of Helen Abbe Howson), 1885. Oil on canvas. Gift of Mrs. Gertrude Farnham Howson, 1974 (74.19.6). hrm.org/museum-from-home 1 Part 1: Introducing Portraiture Portrait painting, or figural painting, is a fine art genre in which the intent is to depict the visual appearance of the subject, typically a person (sometimes multiple people or even an animal). Portraits in different mediums and contexts help us understand the social history of different times. In addition to painting, portraits can also be made in other mediums such as woodcut, engraving, etching, lithography, sculpture, photography, video and digital media. Historically, portrait paintings were made primarily as memorials to and for the rich and powerful. Over time, portrait-making has become much easier for people to do on their own, and portrait commissions are much more accessible than they once were. -

Modernism 1 Modernism

Modernism 1 Modernism Modernism, in its broadest definition, is modern thought, character, or practice. More specifically, the term describes the modernist movement, its set of cultural tendencies and array of associated cultural movements, originally arising from wide-scale and far-reaching changes to Western society in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Modernism was a revolt against the conservative values of realism.[2] [3] [4] Arguably the most paradigmatic motive of modernism is the rejection of tradition and its reprise, incorporation, rewriting, recapitulation, revision and parody in new forms.[5] [6] [7] Modernism rejected the lingering certainty of Enlightenment thinking and also rejected the existence of a compassionate, all-powerful Creator God.[8] [9] In general, the term modernism encompasses the activities and output of those who felt the "traditional" forms of art, architecture, literature, religious faith, social organization and daily life were becoming outdated in the new economic, social, and political conditions of an Hans Hofmann, "The Gate", 1959–1960, emerging fully industrialized world. The poet Ezra Pound's 1934 collection: Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. injunction to "Make it new!" was paradigmatic of the movement's Hofmann was renowned not only as an artist but approach towards the obsolete. Another paradigmatic exhortation was also as a teacher of art, and a modernist theorist articulated by philosopher and composer Theodor Adorno, who, in the both in his native Germany and later in the U.S. During the 1930s in New York and California he 1940s, challenged conventional surface coherence and appearance of introduced modernism and modernist theories to [10] harmony typical of the rationality of Enlightenment thinking. -

John Richard Fudge B

John Richard Fudge b. 1940, Des Moines, IA d. 1999, Lakewood, CO Education 1966 MFA, University of Colorado, Boulder 1963 BFA, University of Colorado, Boulder Solo Exhibitions 2012 John Fudge Paintings and other Allegories, RULE Pop-up at the Pattern Shop Studio 1988 John Fudge: From Hell to Breakfast, Arvada Center for the Arts, Arvada, CO 1983 Twenty-Year Retrospective, Boulder Center for the Visual Arts, Boulder, CO 1978 Regis College, Denver, CO 1977 J. Magnin Gallery, Denver, CO 1974 Walker Street Gallery, New York 1974 Paintings, Wilamaro Gallery, Denver, CO 1972 Wilamaro Gallery, Denver, CO! 1970 Henderson Museum, University of Colorado, Boulder 1968 University of Arizona, Tucson! 1968 University of Colorado, Boulder Select Group Exhibitions 2017 Audacious, Denver Art Museum, Denver, CO 2016 Looking Back: 40 Years/40 Artists, Arvada Center for the Arts, Arvada, CO 2006 The Armory Group: 40 Years, Mizel Center for Arts and Culture, Denver, CO 1999 Using Your Faculties, University of Colorado, Denver, CO 1996 20/20 Vision, Arvada Center for the Arts and Humanities, Arvada, CO! 1995 The 32-Year Show, Emmanuel Gallery, University of Colorado, Denver, CO 1995 John Fudge: Recent Work, Rocky Mountain College of Art and Design, Denver,! CO 1994 Nature Morte, Rule Modern and Contemporary Art, Denver ! 1993 Preternatural Worlds, Center for Visual Arts, Metropolitan State College, Denver, CO 1992 John Fudge and Jim Hayes, Boulder Center for the Visual Arts, Boulder, CO 1990 Fat-Free Surrealism, Michael Leonard Gallery (curator, Red Grooms), -

Artist Bios Alex Katz Is the Author of Invented Symbols

Artist Bios Alex Katz is the author of Invented Symbols: An Art Autobiography. Current exhibitions include “Alex Katz: Selections from the Whitney Museum of American Art” at the Nassau County Museum of Art and “Alex Katz: Beneath the Surface” at the Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art. Jan Henle grew up in St. Croix and now works in Puerto Rico. His film drawings are in the collections of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, and The Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth. His collaborative film with Vivien Bittencourt, Con El Mismo Amor, was shown at the Gwang Ju Biennale in 2008 and is currently in the ikono On Air Festival. Juan Eduardo Gómez is an American painter born in Colombia in 1970. He came to New York to study art and graduated from the School of Visual Arts in 1998. His paintings are in the collections of the High Museum of Art, Atlanta, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and Bowdoin College Museum of Art, Brunswick. He was awarded The Richard and Hilda Rosenthal Foundation Award from American Academy of Arts and Letters in 2007. Rudy Burckhardt was born in Basel in 1914 and moved to New York in 1935. From then on he was at or near the center of New York’s intellectual life, counting among his collaborators Edwin Denby, Paul Bowles, John Ashbery, Frank O’Hara, Kenneth Koch, Alex Katz, Red Grooms, Mimi Gross, and many others. His work has been the subject of exhibitions at the Instituto Valenciano de Arte Moderno, the Museum of the City of New York, and, in 2013, at Museum der Moderne Salzburg. -

Cydney M. Payton 1 Selected Exhibitions

CYDNEY M. PAYTON 2009–present Independent Curator & Writer San Francisco, California 2001–2008 Director & Chief Curator Museum of Contemporary Art Denver, Colorado 1992–2000 Director & Chief Curator Boulder Museum of Contemporary Art, Colorado 1984–1992 Founder & Director Cydney Payton Gallery, Denver, Colorado Payton Rule Gallery, Denver, Colorado SELECTED EXHIBITIONS 2013 Unbuilt San Francisco: The View from Futures Past (co-curator Benjamin Grant) featuring architects: John Bolles, Ernest Born, Mario Ciampi, Vernon DeMars, Lawrence Halprin, Legorreta & Legorreta, Daniel Libeskind, William Merchant, Willis Polk, Kenzo Tange, and Cathy Simon. California Historical Society and SPUR, San Francisco 2012 Temporary Structures (co-curator Glen Helfand) featuring Pawel Althamer, Roberto Behar & Rosario Marquardt, David Gissen, Amy H. Ho, David Ireland, Paul Kos, Roy McMakin, Christian Nagler & Azin Seraj, Ben Peterson, Michael Robinson, Jonathan Runico, Mungo Thomson, Together We Can Defeat Capitalism. San Francisco Institute of Arts (SFAI), San Francisco 2011 On Apology (co-curator) featuring Erick Beltran, Mark Boulos, Keren Cytter, Omer Fast, Shaun Gladwell, Ragnar Kjartansson, Amalia Pica, Slavs and Tatars, Dawn Weleski, Artur Zmijewski. Wattis Institute for Contemporary Arts, California College of the Arts (CCA), San Francisco The Thing Is To See: Selected Photo-Souvenirs of Daniel Buren 1968-1975, online at thethingistosee.com, Steven Leiber Archives, San Francisco Piggly Wiggly: Self-Serving Stores All Over the World, Wattis Institute for Contemporary Arts, California College of the Arts, San Francisco 2010 Yu-Cheng Chou: Because 64 Crayons Made in the USA. Superfrog Gallery, New People, San Francisco 1 CYDNEY M. PAYTON 2009 Heather & Eric Chan Schatz. The Family of Natasha Congdon Large Works Gallery, MCA DENVER Rex Ray. -

Oral History Interview with Red Grooms, 1974 Mar. 4-18

Oral history interview with Red Grooms, 1974 Mar. 4-18 Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a tape-recorded interview with Red Grooms on 1974 March 4-18. The interview was conducted at Grooms' studio by Paul Cummings for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. The reader should bear in mind that he or she is reading a transcript of spoken, rather than written, prose. This is a rough transcription that may include typographical errors. Interview PC: March 4, 1974, Paul Cummings talking to Red Grooms in his studio at 85 Walker Street. You were born in Nashville, Tennessee on June first, 1937. RG: No, on June second. This is getting to be ridiculous. Somebody has got to get this straight. PC: So it is June second? RG: Yes. But now the date is beginning to wander all over the place. I've seen it given as the seventeenth. You see, what happened is that the damn birth certificate—I finally had to get a passport and looked up my birth certificate and it had June first on there. Which I guess is a mistake unless my parents are goofy. So the birth certificate actually showed June first and they really make you put that on the passport even if it's wrong. -

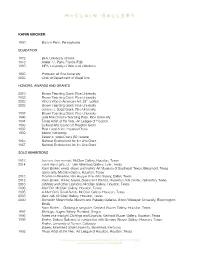

Karin Broker

KARIN BROKER 1950 Born in Penn, Pennsylvania EDUCATION 1972 BFA, University of Iowa 1973 Atelier 17, Paris, France (Fall) 1980 MFA, University of Wisconsin-Madison 1980 Professor at Rice University 2003 Chair of Department of Visual Arts HONORS, AWARDS AND GRANTS 2010 Brown Teaching Grant. Rice University 2008 Brown Teaching Grant. Rice University 2003 Who’s Who in American Art. 25th. Edition 2002 Brown Teaching Grant. Rice University Jerome J. Segal Grant. Rice University 1997 Brown Teaching Grant. Rice University 1996 Julia Mile Chance Teaching Prize. Rice University 1994 Texas Artist of the Year. Art League of Houston 1993 Cultural Arts Council of Houston Grant 1992 Best Local Artist. Houston Press. 1989 Mellon Fellowship Dewar's Texas Doers (50 Texans) 1985 National Endowment for the Arts Grant 1987 National Endowment for the Arts Grant SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2018 love me, love me not, McClain Gallery, Houston, Texas 2014 more damn girls, UT Tyler Meadows Gallery, Tyler, Texas Karin Broker: wired, drawn and nailed, Art Museum of Southeast Texas, Beaumont, Texas damn girls, McClain Gallery, Houston, Texas 2013 Trouble in Paradise, Kirk Hopper Fine Arts Gallery, Dallas, Texas 2012 Karin Broker: Wired, Nailed, Drawn and Printed, Galveston Arts Center, Galveston, Texas 2010 Oddities and Other Opinions, McClain Gallery, Houston, Texas 2006 Mad Girl. McClain Gallery. Houston, Texas 2005 A Mad Girl’s Small Notes. McClain Gallery. Houston, Texas 2003 Dark Talk. McClain Gallery. Houston, Texas 2000 Domestic Melancholia. Merwin and Wakeley Galleries. Illinois Wesleyan University. Bloomington, Illinois Karin Broker….Drawing in sanguine. Gerhard Wurzer Gallery. Houston, Texas 1997 Etchings. Augen Gallery. Portland, Oregon 1996 Notes of a mad girl. -

Mimi Gross Charm of the Many

Mimi Gross Charm of the Many Preface by Dominique Fourcade Text by Charles Bernstein Salander-O’Reilly Galleries New York This catalogue accompanies an exhibition from September 5–28, 2002 at Salander-O'Reilly Galleries, LLC 20 East 79 Street New York, NY 10021 Tel (212) 879-6606 Fax (212) 744-0655 www.salander.com Monday–Saturday 9:30 to 5:30 © 2002 Salander-O’Reilly Galleries, LLC ISBN: 0 -158821-110-X Photography: Paul Waldman Design: Lawrence Sunden, Inc. Printing: The Studley Press TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface 7 Dominique Fourcade Mimi Gross 9 Charles Bernstein Plates 21 Chronology 42 The artist in her studio. Photo: Henry Jesionka. >#< PREFACE Dominique Fourcade Charm of the Many, such a derangement, does not mean that many were charming, nor does it mean that many have a charm. It alludes to a surprise: in the act of painting many a dif- ferent one lies a charm, single, inborn, and the painter is exposed. Is acted. It has to do with unexpectable sameness, it is serendipitous as well as recalcitrant and alarming. It lurks, very real, not behind but in front of the surfaces. It amounts to a lonesome surface, the surface of portraiture, and deals with an absence, because one does not portray life, death is the subject. Death is the component and the span, the deeper one portrays the more it dawns on us. A sameness, not opaque, with a great variety of reso- nances, a repeated syncope. Charm of the Many is to be sensed, obviously, under the light of Mimi’s own Coptic ways, Fayoumesque, on the arduous path of appearance. -

In the Studio

Wendell H. Black 17. Picasso at Mougins: The Etchings, 2002 Erik Desmazières 29. With Aldo Behind Me, 2008 62. Copyists at the Metropolitan Museum, 1908 CHECKLIST (American, 1919–1972) Soft-ground etching, aquatint, sugar-lift (French, born 1948) Aquatint, etching, drypoint, and mechanical Etching; unnumbered edition of 100 1 Dimensions are in inches; 6. Artist and Model—Spring II, 1958 aquatint, with à la poupée inking and relief 25. Atelier René Tazé IV, 1992 abrasion; edition 12/15 plate: 7 /2 x 9 IN THE STUDIO 1 1 1 Woodcut; edition 11/25 rolls through stencils; edition 91/200 Etching, aquatint and roulette; plate: 46 /2 x 38 /2 sheet: 11 x 13 /8 1 5 7 5 3 height precedes width. image: 23 /8 x 38 plate: 17 /8 x 23 /8 edition 16/75 sheet: 54 /8 x 46 /8 Courtesy of Davidson Galleries, Seattle, and 5 7 7 sheet: 28 x 41 sheet: 23 /8 x 30 plate: 25 /8 x 19 /8 Courtesy of Augen Gallery Kraushaar Galleries, New York Reflections on Artistic Life 1 Museum Purchase The Carol and Seymour Haber Collection sheet: 30 x 22 /4 Edward Ardizzone 30. Snips, Pliers, and Hammers, 2011 Raphael Soyer (British, 1900–1979) 92.217.44 2004.33.5 Museum Purchase: Hank and Judy Hummelt Fund Woodcut and etching; edition 12/15 (American, 1899–1987) 1. The Model, 1953 1 FEBRUARy 2 – MAy 19, 2013 Frank Boyden Charles‑François Daubigny 1995.18.1 plate: 48 x 38 /4 63. Young Model, 1940 5 1 Lithograph; edition 29/30 (American, born 1942) (French, 1817–1878) sheet: 50 /8 x 40 /8 Lithograph; unnumbered edition of 250 1 5 8 8 3 image: 8 / x 10 / 7. -

FOR the PAST Four Decades, Mimi Gross Has Lived and Worked in a Broad, Art-Filled Loft Just Below Canal Street in Manhattan

Critical Eye: Mimi Gross in Her World By Dan Nadel, January 27, 2017 FOR THE PAST four decades, Mimi Gross has lived and worked in a broad, art-filled loft just below Canal Street in Manhattan. Visitors are greeted by an enormous and exuberant painted sculpture—Gross calls it a “2½-D” work—in which the artist portrays her friends from the heyday of New York’s downtown bohemia in the poses and setting of Delacroix’s Women of Algiers in their Apartment (1834). It is, like so many things Gross does, a deft blending of history, observational por- traiture, and ingenious craft. The walls of her studio are covered with artwork by old comrades and family friends, a cast that includes both giants of American art and under-recognized figures: Rudy Burckhardt, Yvonne Jacquette, Saul Steinberg, Karl Wirsum, Sarah Canright. Mixed in are pieces by her ex-husband, Red Grooms, and her father, Chaim Gross. In her bright white workspace on the day I visited in late summer were several works in progress, including sets and costumes for Antipodes, Mimi Gross, At the Five Spot, 1958-1959, oil on the latest in more than a dozen collaborations she has undertaken crayon on paper, 13 3/4 x 10 3/4 in. with choreographer Douglas Dunn, and a 170-foot-long painting of clouds commissioned by the University of Ken- tucky Medical Center. Less spectacular but perhaps more enticing were flat files stacked to the ceiling along one wall of the studio. Each drawer holds its own delights. Some feature preparatory drawings from Gross’s pioneering films, such as Tap- py Toes (1969–70), a hilarious and surreal homage to Busby Berkeley. -

Exhibition Gazette (PDF)

ARTIST-RUN GALLERIES IN NEW YORK CITY Inventing 1952–1965 Downtown JANUARY 10–APRIL 1, 2017 Grey Gazette, Vol. 16, No. 1 · Winter 2017 · Grey Art Gallery New York University 100 Washington Square East, NYC InventingDT_Gazette_9_625x13_12_09_2016_UG.indd 1 12/13/16 2:15 PM Danny Lyon, 79 Park Place, from the series The Destruction of Lower Manhattan, 1967. Courtesy the photographer and Magnum Photos Aldo Tambellini, We Are the Primitives of a New Era, from the Manifesto series, c. 1961. JOIN THE CONVERSATION @NYUGrey InventingDowntown # Aldo Tambellini Archive, Salem, Massachusetts This issue of the Grey Gazette is funded by the Oded Halahmy Endowment for the Arts; the Boris Lurie Art Foundation; the Foundation for the Arts. Inventing Downtown: Artist-Run Helen Frankenthaler Foundation; the Art Dealers Association Galleries in New York City, 1952–1965 is organized by the Grey Foundation; Ann Hatch; Arne and Milly Glimcher; The Cowles Art Gallery, New York University, and curated by Melissa Charitable Trust; and the Japan Foundation. The publication Rachleff. Its presentation is made possible in part by the is supported by a grant from Furthermore: a program of the generous support of the Terra Foundation for American Art; the J.M. Kaplan Fund. Additional support is provided by the Henry Luce Foundation; The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Grey Art Gallery’s Director’s Circle, Inter/National Council, and Visual Arts; the S. & J. Lurje Memorial Foundation; the National Friends; and the Abby Weed Grey Trust. GREY GAZETTE, VOL. 16, NO. 1, WINTER 2017 · PUBLISHED BY THE GREY ART GALLERY, NYU · 100 WASHINGTON SQUARE EAST, NYC 10003 · TEL. -

Red Grooms Artist CV

Marlborough RED GROOMS 1937— Born in Nashville, Tennessee. The artist lives and works in New York, New York. Education 1957— Hans Hoffman School of Fine Arts, Provincetown, Massachusetts 1956— George Peabody College for Teachers, Nashville, Tennessee The New School, New York, New York 1955— School of the Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois Solo Exhibitions 2021— Red Grooms, Marlborough Gallery, New York, New York 2020— Ruckus Rodeo, The Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, Fort Worth, Texas 2018— Handiwork, 1955 – 2018, Marlborough Contemporary, New York, New York Red Grooms: A Retrospective, Tennessee State Museum, Nashville, Tennessee 2017— New York On My Mind, Marlborough Gallery, New York, New York 2016— Lincoln on the Hudson by Red Grooms, Hudson River Museum, Yonkers, New York Red Grooms: Traveling Correspondent, Memphis Brooks Museum of Art, Memphis, Tennessee 2015— Red Grooms: The Blue & The Gray, Tennessee State Museum, Nashville, Tennessee; traveled to Hudson River Museum, Yonkers, New York 2014— Red Grooms: Torn from the Pages II, Marlborough Gallery, New York, New York Red Grooms: Beware a Wolf in the Alley, Marlborough Broome Street, New York, New York Marlborough 2013— Red Grooms’ New York City, Children’s Museum of Manhattan, New York, New York Red Grooms: What’s the Ruckus, Brattleboro Museum & Art Center, Brattleboro, Vermont Red Grooms: Larger Than Life, Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, Connecticut 2012— Torn from the Pages, Marlborough Gallery, New York, New York 2011— Red Grooms, New York: 1976-2011, Marlborough