“IRISH PAT” MCMURTRY Heavyweight Title Contender & Tacoma Native Son by Peter Bacho

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mike Tyson Brings His Undisputed: Round 2 Tour to Four Winds New Buffalo’S Silver Creek Event Center on Friday, July 10

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE MIKE TYSON BRINGS HIS UNDISPUTED: ROUND 2 TOUR TO FOUR WINDS NEW BUFFALO’S SILVER CREEK EVENT CENTER ON FRIDAY, JULY 10 Tickets go on sale on Friday, April 10 NEW BUFFALO, Mich. – April 8, 2020 – The Pokagon Band of Potawatomi’s Four Winds® Casinos are pleased to announce that Mike Tyson will bring his Undisputed Truth: Round 2 tour to Four Winds New Buffalo’s Silver Creek® Event Center on Friday, July 10, at 9 p.m. The one-man show features the world’s most illustrious heavyweight boxing champion, who returns to the stage with real life untold stories, focusing on the ups and downs of his tumultuous and ultimately triumphant, post-boxing life and career. In an up-close-and-personal setting featuring images and videos, Tyson delivers captivating vignettes from his life, experiences as a professional athlete and controversies in between. It’s truly raw and electric theater, in its purest form. Ticket prices for the show range from $55 to $85, plus applicable fees, and can be purchased online at www.fourwindscasino.com beginning on Friday, April 10 at 10 a.m. Eastern. Mike Tyson is a larger-than-life legend – both in and out of the ring. Tenacious, talented, and thrilling to watch, Tyson embodies the grit and electrifying excitement of the sport. With nicknames such as Iron Mike, Kid Dynamite, and The Baddest Man on the Planet, it’s no surprise that Tyson’s legacy is the stuff of a legend. Tyson was one of the most feared boxers in the ring, and one look at his resume proves he is one of boxing’s greats. -

Tsnfiwvsimr TIRES Te«Gg?L

DUE TO NEIGHBORHOOD PRESSURE Tulloch, Aussie Mays Unable to Buy Terps Fly to Face " i-', j 5 '*¦ 1 ' '''''¦- r_ ?-‘1 San Francisco Home Wonder Horse, Tough Miami Battle By MERRELL WHITTLESEY burgh remaining on their SAN FRANCISCO. Nov. 14 want you. what's the good of Star Staff Correspondent schedule. |H (JP>. —Willie Mays’ attempt to buying,’’ Mays continued. MIAMI, Nov. 14—For the Coming to U. This comeback has placed / S. yester- buy a house here failed ’’Blittalk about a thing like second straight week Maryland the Hurricanes on the list of day Jjecause he is a Negro. this goes all over the world, SYDNEY, Australia, Nov. 14 is facing a predominantly eligibles P).—Tulloch, Australia’s for Jacksonville’s The spectacular, 27-year-old and it sure looks bad for our 0 1 new young team with a late-season Gator Bowl, providing, of of San ; country.” wonder horse which is being kick when the Terps meet course, centerflelder the Fran- greater they win their last three cisco Giants offered the $37,- Mays’ wife, Marghuerite, acclaimed as than the | Miami here tomorrow night. It games. quite as philosophical famous Pliar Lap. is ,being 500 asked by the owner for a ; wasn't bears out Coach Tommy Mont's Gator Bowl officials new house 175 Miraloma about It. “Down in Alabama readied foj a campaign in the earlier statement listed at States, ; that this Miami as one of nine teams un- drive, but was turned down where we come from,” she United with the ulti- year's schedule should have mate a der consideration. -

Dec 2004 Current List

Fighter Opponent Result / RoundsUnless specifiedDate fights / Time are not ESPN NetworkClassic, Superbouts. Comments Ali Al "Blue" Lewis TKO 11 Superbouts Ali fights his old sparring partner Ali Alfredo Evangelista W 15 Post-fight footage - Ali not in great shape Ali Archie Moore TKO 4 10 min Classic Sports Hi-Lites Only Ali Bob Foster KO 8 21-Nov-1972 ABC Commentary by Cossell - Some break up in picture Ali Bob Foster KO 8 21-Nov-1972 British CC Ali gets cut Ali Brian London TKO 3 B&W Ali in his prime Ali Buster Mathis W 12 Commentary by Cossell - post-fight footage Ali Chuck Wepner KO 15 Classic Sports Ali Cleveland Williams TKO 3 14-Nov-1966 B&W Commentary by Don Dunphy - Ali in his prime Ali Cleveland Williams TKO 3 14-Nov-1966 Classic Sports Ali in his prime Ali Doug Jones W 10 Jones knows how to fight - a tough test for Cassius Ali Earnie Shavers W 15 Brutal battle - Shavers rocks Ali with right hand bombs Ali Ernie Terrell W 15 Feb, 1967 Classic Sports Commentary by Cossell Ali Floyd Patterson i TKO 12 22-Nov-1965 B&W Ali tortures Floyd Ali Floyd Patterson ii TKO 7 Superbouts Commentary by Cossell Ali George Chuvalo i W 15 Classic Sports Ali has his hands full with legendary tough Canadian Ali George Chuvalo ii W 12 Superbouts In shape Ali battles in shape Chuvalo Ali George Foreman KO 8 Pre- & post-fight footage Ali Gorilla Monsoon Wrestling Ali having fun Ali Henry Cooper i TKO 5 Classic Sports Hi-Lites Only Ali Henry Cooper ii TKO 6 Classic Sports Hi-Lites Only - extensive pre-fight Ali Ingemar Johansson Sparring 5 min B&W Silent audio - Sparring footage Ali Jean Pierre Coopman KO 5 Rumor has it happy Pierre drank before the bout Ali Jerry Quarry ii TKO 7 British CC Pre- & post-fight footage Ali Jerry Quarry ii TKO 7 Superbouts Ali at his relaxed best Ali Jerry Quarry i TKO 3 Ali cuts up Quarry Ali Jerry Quarry ii TKO 7 British CC Pre- & post-fight footage Ali Jimmy Ellis TKO 12 Ali beats his old friend and sparring partner Ali Jimmy Young W 15 Ali is out of shape and gets a surprise from Young Ali Joe Bugner i W 12 Incomplete - Missing Rds. -

Member Motion City Council MM20.14

Member Motion City Council Notice of Motion MM20.14 ACTION Ward:19 Creation and Installation of a Plaque Commemorating The People’s Champion - Muhammad Ali - by Councillor Mike Layton, seconded by Councillor Kristyn Wong-Tam * Notice of this Motion has been given. * This Motion is subject to referral to the Executive Committee. A two-thirds vote is required to waive referral. Recommendations Councillor Mike Layton, seconded by Councillor Kristyn Wong-Tam, recommends that: 1. City Council increase the approved 2016 Operating Budget for Heritage Toronto by $3,250 gross, $0 net, fully funded by Section 37 community benefits obtained in the development at 700 King Street West (Source Account: XR3026-3700113), for the production and installation of a plaque commemorating the life and career in Toronto of Muhammad Ali. 2. City Council direct that the funds be transferred to Heritage Toronto subject to the condition that the Historical Plaques Committee of Heritage Toronto approve of the plaque subject matter. Summary Heritage Toronto is working with local residents to commemorate Muhammad Ali's 1966 visit to Toronto, including his fight against George Chuvalo. Muhammed Ali was one of the world's most celebrated athletes, best-known personalities, and influential civil rights activists. Ali’s enduring fight against oppression and involvement in the black freedom struggle is part of what brought him to Toronto. In March 1966, Ali was booked to fight Ernie Terrell in Chicago, but his controversial anti-war views and refusal to join the United States draft resulted in Chicago and every major United States boxing centre refusing to host the fight, forcing the organizers to move it to Toronto and arrange an alternative opponent - Canadian heavyweight champion, George Chuvalo. -

Online Newsletter Issue 13 October 2013

Online Newsletter Issue 13 October 2013 The IBRO online newsletter is an extension of the Quarterly IBRO Journal and contains material not included in the latest issue of the Journal. Newsletter Features 50 Years After Death, Ohio Honors Boxer Davey Moore by Mike Foley California Calling for Joey Giambra by Mike Casey Remembering A Forgotten Contender: Ibar Arrington by Steve Canton The Boxing Biographies Volume # 9: George “Kid” Lavigne by Rob Snell Book Recommendation: Muscle and Mayhem: The Saginaw Kid (Kid Lavigne) and The Fistic World of the 1890s by Lauren D. Chouinard. Book Review Tale of The “Kid” by Randi Bjornstad, The Register Guard Member inquiries, nostalgic articles, and obituaries submitted by several members. Special thanks to Mike Casey, Steve Canton, Henry Hascup, J.J. Johnston, Rick Kilmer, Harry Otty and Rob Snell, for their contributions to this issue of the newsletter. Keep Punching! Dan Cuoco International Boxing Research Organization Dan Cuoco Director, Editor and Publisher [email protected] All material appearing herein represents the views of the respective authors and not necessarily those of the International Boxing Research Organization (IBRO). © 2013 IBRO (Original Material Only) CONTENTS DEPARTMENTS 3 Member Forum 5 IBRO Apparel 43 Final Bell FEATURES 6 50 Years After Death, Ohio Honors Boxer Davey Moore by Mike Foley 8 California Calling for Joey Giambra by Mike Casey 11 Remembering A Forgotten Contender: Ibar Arrington by Steve Canton 14 The Boxing Biographies Volume #9: George “Kid” Lavigne by Rob Snell BOOK RECOMMENDATIONS & REVIEWS 33 Muscle and Mayhem: The Saginaw Kid (Kid Lavigne) and The Fistic World of the 1890s by Lauren D. -

2014 Fight to End Cancer Gala 2014 Defeat Is Not an Option

OFFICIAL MAGAZINE ANNUAL ISSUE 2014 FIGHT TO END CANCER GALA 2014 DEFEAT IS NOT AN OPTION Feature articles inside: > Fight To End Cancer Reinforces presents Photography by alquintero.com Toronto as a Champion in Boxing > Advocate praises ‘Hurricane’ Carter’ legacy of hope ABOUT THE EVent THE PUrpoSE FUndraiSing The third annual Fight To End Cancer Those who have been affected by InitiatiVES takes place on Saturday, May 31st cancer have had to fight! Fight To Thanks to the strong financial and 2014, at the Old Mill Inn. This gala End Cancer raises funds for cancer gift in-kind donations from all of our event includes not only an elegant research with proceeds going directly corporate sponsors – coupled with gourmet dinner but also features to support the Princess Margaret support from local small businesses a full evening of Las Vegas style Cancer Foundation and its Hospital and community residents – the Fight entertainment including the night’s main Urgent Cancer Priorities Fund. To End Cancer has managed to event – a series of Olympic style boxing This gala event is just one part of an successfully raise over $160,000.00 bouts featuring some of Toronto’s most ongoing fundraising effort which will in support of the Princess Margaret influential and successful business continue throughout the year, and Cancer Foundation, in our first two professionals. whose success will, in large part, rely years of operation. The Fight To End on corporate sponsorship, community Cancer is on its way to becoming one support and continued media of the most recognized and prestigious exposure. With these efforts, Fight To corporate occasions within Toronto and End Cancer is confident to reach its the surrounding GTA. -

Rules and Regulations of the World Boxing

WORLD BOXING COUNCIL RULES & REGULATIONS OF THE WORLD BOXING COUNCIL (“WBC”) 1. ARTICLE I - APPLICABILITY AND INTERPRETATION 1.1 Applicability and Interpretation of these Rules & Regulations. In all WBC-sanctioned championship and elimination contests, these Rules & Regulations, the WBC Championship Rules as promulgated by the WBC from time to time, and all other rules, regulations and rulings issued by the WBC shall apply, unless a written modification or an exception is issued by the WBC in its sole discretion on a case-by-case basis. The WBC shall have sole authority and discretion to interpret these Rules & Regulations. All actions and positions of the WBC shall be interpreted solely in accordance with these Rules & Regulations, which for the limited purpose of interpreting these Rules & Regulations shall supersede and control any conflict or inconsistency with any enforceable national or local law, or with any applicable regulation of a boxing commission. These Rules & Regulations are promulgated in the WBC’s official languages of English and Spanish. In the event of any inconsistency, or conflict of interpretation or translation, between the English and Spanish versions, the English version shall control. Any reference in these Rules & Regulations to the masculine gender shall be taken to include the feminine gender, as applicable. 1.2 Interpretation of Rules and Power of WBC President to Act in the Best Interests of Boxing. As special and unique circumstances arise in the sport of boxing, not all of which can be anticipated and addressed specifically in these Rules & Regulations, the WBC President and Presidency, in consultation with the WBC Board of Governors, has full power and authority to interpret these Rules & Regulations, and to issue and apply such rulings as he shall in his sole discretion deem to be in the best interests of boxing. -

BCN 205 Woodland Park No.261 Georgetown, TX 78633 September-October 2011

BCN 205 Woodland Park no.261 Georgetown, TX 78633 september-october 2011 FIRST CLASS MAIL Olde Prints BCN on the web at www.boxingcollectors.com The number on your label is the last issue of your subscription PLEASE VISIT OUR WEBSITE AT WWW.HEAVYWEIGHTCOLLECTIBLES.COM FOR RARE, HARD-TO-FIND BOXING ITEMS SUCH AS, POSTERS, AUTOGRAPHS, VINTAGE PHOTOS, MISCELLANEOUS ITEMS, ETC. WE ARE ALWAYS LOOKING TO PURCHASE UNIQUE ITEMS. PLEASE CONTACT LOU MANFRA AT 718-979-9556 OR EMAIL US AT [email protected] 16 1 JO SPORTS, INC. BOXING SALE Les Wolff, LLC 20 Muhammad Ali Complete Sports Illustrated 35th Anniver- VISIT OUR WEBSITE: sary from 1989 autographed on the cover Muhammad Ali www.josportsinc.com Memorabilia and Cassius Clay underneath. Recent autographs. Beautiful Thousands Of Boxing Items For Sale! autographs. $500 BOXING ITEMS FOR SALE: 21 Muhammad Ali/Ken Norton 9/28/76 MSG Full Unused 1. MUHAMMAD ALI EXHIBITION PROGRAM: 1 Jack Johnson 8”x10” BxW photo autographed while Cham- Ticket to there Fight autographed $750 8/24/1972, Baltimore, VG-EX, RARE-Not Seen Be- pion Rare Boxing pose with PSA and JSA plus LWA letters. 22 Muhammad Ali vs. Lyle Alzado fi ght program for there exhi- fore.$800.00 True one of a kind and only the second one I have ever had in bition fi ght $150 2. ALI-LISTON II PRESS KIT: 5/25/1965, Championship boxing pose. $7,500 23 Muhammad Ali vs. Ken Norton 9/28/76 Yankee Stadium Rematch, EX.$350.00 2 Jack Johnson 3x5 paper autographed in pencil yours truly program $125 3. -

Npc Bodybuilding Division Rules

NATIONAL PHYSIQUE COMMITTEE OF THE USA PO Box 3711, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15230 USA TOLL FREE: 1-866-304-4322 PHONE: 412-276-5027 FAX: 412-281-0471 EMAIL: [email protected] WEB: www.NPCnewsOnline.com NPC BODYBUILDING DIVISION RULES Posing Music • Posing Music will be used at the Finals only. • Posing Music must be on CD and must be the only music on the CD. • Posing Music should be cued to the start of the music. N • Posing Music must not contain vulgar lyrics. Competitors Membership using music containing vulgar lyrics will be disqualifi ed. Each competitor must be a member of the NPC. Onstage Complete Registration Card • During the Prejudging male and female competitors are not on the back of this Issue. permitted to wear any jewelry onstage other than a wedding band. Decorative pieces in the hair are not permitted. • During the Finals female competitors are permitted to wear earrings. Competitor Rules • No glasses, props or gum are permitted onstage. • Any competitor doing the “Moon Pose” will be disqualifi ed. Check-Ins • Lying on the fl oor is prohibited. Competitors will be checked in and weighed. • Bumping and shoving is prohibited. First and second persons involved will be disqualifi ed. Posing Suits • Competitors numbers will be worn on the left side of the suit • All suit bottoms must be V-shaped, no thongs are permitted. bottom during both Prejudging and Finals. • Suits worn by male competitors at the prejudging and fi nals must be plain in color with no fringe, wording, sparkle Backstage or fl uorescents. The only people permitted in the backstage area are: • Suits worn by female competitors at the Prejudging must be • Competitors two-piece and plain in color with no fringe, wording, sparkle • Expediters or fl uorescents. -

Boxing Edition

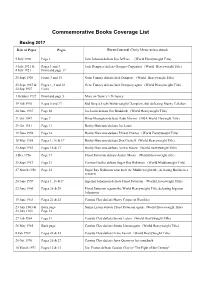

Commemorative Books Coverage List Boxing 2017 Date of Paper Pages Event Covered (Daily Mirror unless stated) 5 July 1910 Page 3 Jack Johnson defeats Jim Jeffries (World Heavyweight Title) 3 July 1921 & Pages 1 and 3 Jack Dempsey defeats Georges Carpentier (World Heavyweight Title) 4 July 1921 Front and page 17 25 Sept 1926 Front, 3 and 15 Gene Tunney defeats Jack Dempsey (World Heavyweight Title) 23 Sept 1927 & Pages 1, 3 and 18 Gene Tunney defeats Jack Dempsey again (World Heavyweight Title) 24 Sep 1927 Front 1 October 1927 Front and page 5 More on Tunney v Dempsey 19 Feb 1930 Pages 5 and 22 Kid Berg is Light Welterweight Champion after defeating Mushy Callahan 24 June 1937 Page 30 Joe Louis defeats Jim Braddock (World Heavyweight Title) 21 Oct 1947 Page 7 Rinty Monaghan defeats Dado Marino (NBA World Flyweight Title) 29 Oct 1951 Page 11 Rocky Marciano defeats Joe Louis 19 June 1954 Page 14 Rocky Marciano defeats Ezzard Charles (World Heavyweight Title) 18 May 1955 Pages 1, 16 & 17 Rocky Marciano defeats Don Cockell (World Heavyweight Title) 23 Sept 1955 Pages 16 & 17 Rocky Marciano defeats Archie Moore (World Heavyweight Title) 3 Dec 1956 Page 17 Floyd Patterson defeats Archie Moore (World Heavyweight title) 25 Sept 1957 Page 23 Carmen Basilio defeats Sugar Ray Robinson (World Middleweight Title) 27 March 1958 Page 23 Sugar Ray Robinson wins back the Middleweight title, defeating Basilio in a rematch 28 June 1959 Pages 1, 16 &17 Ingemar Johansson defeats Floyd Patterson (World Heavyweight Title) 22 June 1960 Pages 28 & 29 Floyd Patterson -

Theboxing Biographies Newsletter Volume3 - No 11 25Th Dec, 2008

1 TheBoxing Biographies Newsletter Volume3 - No 11 25th DEc, 2008 www.boxingbiographies.com If you wish to receive future newsletters ( which includes the images ) please email the message “NEWS LETTER” [email protected] The newsletter is also available as a word doc on request As always the full versions of these articles are on the website My very best wishes to all my readers and thank you for the continued support you have given which I do appreciate a great deal. Name: Willie Pastrano Career Record: click Birth Name: Wilfred Raleigh Pastrano Nationality: US American Hometown: New Orleans, Louisiana, USA Born: 1935-11-27 Died: 1997-12-06 Age at Death: 62 Stance: Orthodox Height: 6′ 0″ Trainers: Angelo Dundee & Whitey Esneault Manager: Whitey Esneault Wilfred Raleigh Pastrano was born in the Vieux Carrê district of New Orleans, Louisiana, on 27 November 1935. He had a hard upbringing, under the gaze of a strict father who threatened him with the belt if he caught him backing off from a confrontation. 'I used to run from fights,' he told American writer Peter Heller in 1970. 'And papa would see it from the steps. He'd take his belt, he'd say "All right, me or him?" and I'd go beat the kid: His father worked wherever and whenever he could, in shipyards and factories, sometimes as a welder, sometimes as a carpenter. 'I remember nine dollars a week paychecks,' the youngster recalled. 'Me, my mother, my step-brother, and my father and whatever hangers-on there were...there were always floaters in the family.' Pastrano was an overweight child but, like millions of youngsters at the time, he wanted to be a sports star like baseball's Babe Ruth. -

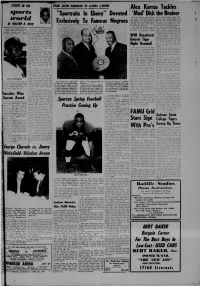

Alex Karras Tackles

[vinjs m m FROM JACKIE ROBINSON TO ALTHEA GIBSON: Alex Karras Tackles sports "Sportraits In Ebony" Devoted 'Mad' Dick the Bruiser Big Alex Karras, the tremend fend which began when The ous tackle of the Detroit Liorui, Bruiser, in his usual lactiul way, world will battle Dick the Bruiser in sneered that ‘ Karras hasn't got Exclusively To Famous Negroes the lug bout on another all star the nerve to wrestle me. That wrestling program a the Olym- is why he takes out his evil tem- tr wum s. son pia Stadium. April 27, per on little basketball plavers. " This collision between two of He's just an oversized bum the biggest and tougest athletes This seemed to incense Karras, A look at the American Lcag Comparing club and the averages hitting we find in the U S. climaxes a bitter long a storm center with the ue Clubs of -he Tjr»nrs individual players will reveal I finished ninth out of !.ion s and a man who never back- ten teams challenge why the Tißcrs were in trouble with a 248 average The ed down lrom a yet °nly team they out hit was the c "The Bruiser is all mouth,” 1 ri„v<»»*>n't Indians The Tigers WJR Broadcasts declared Karras "I'm tired of ] got 1.112 hits to 11m Indian’s 13- getting pushed around, and I'm M while the New vork Yankees Detroit Tiger certainly hot going to take from bd Ihe league w'lh 1509 hits an oversize phoney like The bright , The one area in the hatt- Bruiser.