Introductions to Heritage Assets: Post-Modern Architecture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

12. Selma Harrington Et Al 11-3-178-192

Selma Harrington, Branka Dimitrijević, Ashraf M. Salama Archnet-IJAR, Volume 11 - Issue 3 - November 2017 - (178-192) – Regular Section Archnet-IJAR: International Journal of Architectural Research www.archnet-ijar.net/ -- https://archnet.org/collections/34 MODERNIST ARCHITECTURE, CONFLICT, HERITAGE AND RESILIENCE: THE CASE OF THE HISTORICAL MUSEUM OF BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.26687/archnet-ijar.v11i3.1330 Selma Harrington, Branka Dimitrijević, Ashraf M. Salama Keywords Abstract Bosnia and Herzegovina; Bosnia and Herzegovina is one of the successor states of conflict and identity former Yugoslavia, with a history of dramatic conflicts and narratives; Modernist ruptures. These have left a unique heritage of interchanging architecture; public function; prosperity and destruction, in which the built environment and resilience; reuse of architecture provide a rich evidence of the many complex architectural heritage identity narratives. The public function and architecture of the Historical Museum of Bosnia and Herzegovina, once purposely built to commemorate the national liberation in World War 2, encapsulates the current situation in the country, which is navigating through a complicated period of reconstruction and transformation after the war in 1990s. Once considered as the embodiment of a purist Modernist architecture, now a damaged structure with negligible institutional patronage, the Museum shelters the fractured artefacts of life during the three and a half year siege of ArchNet -IJAR is indexed and Sarajevo. This paper introduces research into symbiotic listed in several databases, elements of architecture and public function of the Museum. including: The impact of conflict on its survival, resilience and continuity of use is explored through its potentially mediatory role, and • Avery Index to Architectural modelling for similar cases of reuse of 20th century Periodicals architectural heritage. -

Remembering Robert Venturi, a Modern Mannerist

The Plan Journal 4 (1): 253-259, 2019 doi: 10.15274/tpj.2019.04.01.1 Remembering Robert Venturi, a Modern Mannerist In Memoriam / THEORY Maurizio Sabini After the generation of the “founders” of the Modern Movement, very few architects had the same impact that Robert Venturi had on architecture and the way we understand it in our post-modern era. Aptly so and with a virtually universal consensus, Vincent Scully called Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture (1966) “probably the most important writing on the making of architecture since Le Corbusier’s Vers une architecture, of 1923.” 1 And I would submit that no other book has had an equally consequential impact ever since, even though Learning from Las Vegas (published by Venturi with Denise Scott Brown and Steven Izenour in 1972) has come quite close. As Aaron Betsky has observed: Like the Modernism that Venturi sought to nuance and enrich, many of the elements for which he argued were present in even the most reduced forms of high Modernism. Venturi was trying to save Modernism from its own pronouncements more than from its practices. To a large extent, he won, to the point now that we cannot think of architecture since 1966 without reference to Robert Venturi.2 253 The Plan Journal 4 (1): 253-259, 2019 - doi: 10.15274/tpj.2019.04.01.1 www.theplanjournal.com Figure 1. Robert Venturi, Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture (London: The Architectural Press, with the Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1977; or. ed., New York: The Museum of Art, 1966). -

Imperial War Museum Annual Report and Accounts 2019-20

Imperial War Museum Annual Report and Accounts 2019-20 Presented to Parliament pursuant to section 9(8) Museums and Galleries Act 1992 Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed on 7 October 2020 HC 782 © Crown copyright 2020 This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3. Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. This publication is available at: www.gov.uk/official-documents. Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us at [email protected] ISBN 978-1-5286-1861-8 CCS0320330174 10/20 Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fibre content minimum Printed in the UK by the APS Group on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office 2 Contents Page Annual Report 1. Introduction 4 2. Strategic Objectives 5 3. Achievements and Performance 6 4. Plans for Future Periods 23 5. Financial Review 28 6. Staff Report 31 7. Environmental Sustainability Report 35 8. Reference and Administrative Details of the Charity, 42 the Trustees and Advisers 9. Remuneration Report 47 10. Statement of Trustees’ and Director-General’s Responsibilities 53 11. Governance Statement 54 The Certificate and Report of the Comptroller and Auditor 69 General to the Houses of Parliament Consolidated Statement of Financial Activities 73 The Statement of Financial Activities 74 Consolidated and Museum Balance Sheets 75 Consolidated Cash Flow Statement 76 Notes to the financial statements 77 3 1. -

Protecting Postmodern Historicism: Identification, Ve Aluation, and Prescriptions for Preeminent Sites

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Theses (Historic Preservation) Graduate Program in Historic Preservation 2013 Protecting Postmodern Historicism: Identification, vE aluation, and Prescriptions for Preeminent Sites Jonathan Vimr University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses Part of the Historic Preservation and Conservation Commons Vimr, Jonathan, "Protecting Postmodern Historicism: Identification, vE aluation, and Prescriptions for Preeminent Sites" (2013). Theses (Historic Preservation). 211. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/211 Suggested Citation: Vimr, Jonathan (2013). Protecting Postmodern Historicism: Identification, vE aluation, and Prescriptions for Preeminent Sites. (Masters Thesis). University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/211 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Protecting Postmodern Historicism: Identification, vE aluation, and Prescriptions for Preeminent Sites Abstract Just as architectural history traditionally takes the form of a march of styles, so too do preservationists repeatedly campaign to save seminal works of an architectural manner several decades after its period of prominence. This is currently happening with New Brutalism and given its age and current unpopularity will likely soon befall postmodern historicism. In hopes of preventing the loss of any of the manner’s preeminent works, this study provides professionals with a framework for evaluating the significance of postmodern historicist designs in relation to one another. Through this, the limited resources required for large-scale preservation campaigns can be correctly dedicated to the most emblematic sites. Three case studies demonstrate the application of these criteria and an extended look at recent preservation campaigns provides lessons in how to best proactively preserve unpopular sites. -

An Introduction to Architectural Theory Is the First Critical History of a Ma Architectural Thought Over the Last Forty Years

a ND M a LLGR G OOD An Introduction to Architectural Theory is the first critical history of a ma architectural thought over the last forty years. Beginning with the VE cataclysmic social and political events of 1968, the authors survey N the criticisms of high modernism and its abiding evolution, the AN INTRODUCT rise of postmodern and poststructural theory, traditionalism, New Urbanism, critical regionalism, deconstruction, parametric design, minimalism, phenomenology, sustainability, and the implications of AN INTRODUCTiON TO new technologies for design. With a sharp and lively text, Mallgrave and Goodman explore issues in depth but not to the extent that they become inaccessible to beginning students. ARCHITECTURaL THEORY i HaRRY FRaNCiS MaLLGRaVE is a professor of architecture at Illinois Institute of ON TO 1968 TO THE PRESENT Technology, and has enjoyed a distinguished career as an award-winning scholar, translator, and editor. His most recent publications include Modern Architectural HaRRY FRaNCiS MaLLGRaVE aND DaViD GOODmaN Theory: A Historical Survey, 1673–1968 (2005), the two volumes of Architectural ARCHITECTUR Theory: An Anthology from Vitruvius to 2005 (Wiley-Blackwell, 2005–8, volume 2 with co-editor Christina Contandriopoulos), and The Architect’s Brain: Neuroscience, Creativity, and Architecture (Wiley-Blackwell, 2010). DaViD GOODmaN is Studio Associate Professor of Architecture at Illinois Institute of Technology and is co-principal of R+D Studio. He has also taught architecture at Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design and at Boston Architectural College. His work has appeared in the journal Log, in the anthology Chicago Architecture: Histories, Revisions, Alternatives, and in the Northwestern University Press publication Walter Netsch: A Critical Appreciation and Sourcebook. -

Greenwich Park

GREENWICH PARK CONSERVATION PLAN 2019-2029 GPR_DO_17.0 ‘Greenwich is unique - a place of pilgrimage, as increasing numbers of visitors obviously demonstrate, a place for inspiration, imagination and sheer pleasure. Majestic buildings, park, views, unseen meridian and a wealth of history form a unified whole of international importance. The maintenance and management of this great place requires sensitivity and constant care.’ ROYAL PARKS REVIEW OF GREEWNICH PARK 1995 CHAIRMAN’S FOREWORD Greenwich Park is England’s oldest enclosed public park, a Grade1 listed landscape that forms two thirds of the Maritime Greenwich World Heritage Site. The parks essential character is created by its dramatic topography juxtaposed with its grand formal landscape design. Its sense of place draws on the magnificent views of sky and river, the modern docklands panorama, the City of London and the remarkable Baroque architectural ensemble which surrounds the park and its established associations with time and space. Still in its 1433 boundaries, with an ancient deer herd and a wealth of natural and historic features Greenwich Park attracts 4.7 million visitors a year which is estimated to rise to 6 million by 2030. We recognise that its capacity as an internationally significant heritage site and a treasured local space is under threat from overuse, tree diseases and a range of infrastructural problems. I am delighted to introduce this Greenwich Park Conservation Plan, developed as part of the Greenwich Park Revealed Project. The plan has been written in a new format which we hope will reflect the importance that we place on creating robust and thoughtful plans. -

Baroque & Modern Expression

HISTORY OF ARCHITECTURAL THEORY, 48-311, Fall 2016 Prof. Gutschow, Week #4 Week #4: BAROQUE & MODERN EXPRESSION Tu./Th. Sept. 20/22 Required Readings for all Students: * H.F. Mallgrave, Architectural Theory: Vol.1: An Anthology from Vitruvius to 1870 (2006), pp.48-55, 57-117, 223-248. Focus especially on readings #29,31,32,34,35,37,39,40,92,94,99,100. Questions to think about: In your reading of the many excerpts associated with the Baroque, attempt to get an overview of how the Baroque period and mood is different than the Renaissance. What was the “battle of the ancients & moderns,” and who were the main players? How does the architectural theory conversation in France compare to that in England? What is “Palladianism,” and how does it relate to the “Baroque”? How does garden design start to skew the theoretical trajectory in England? What is “the picturesque”? * Perrault, C. Ordonnance for the Five Kinds of Columns after the Method of the Ancients = Ordonnances des Cinq Espèces de Colonne, intro. A. Pérez-Gómez (1683, 1993) pp.47-63, 65-66, 94-95, 153-154, skim155-175 Questions to think about: What are “Postive” and “Arbitrary” beauty? Which does Perrault favor? Why? What is Perrault’s attitude towards the “ancients”? How do Perrault’s Baroque ideas challenge Vitruvius and Renaissance architectural theory? Assigned/Other Readings: Questions to think about for all readings: What attributes does each author give to the Baroque, as opposed to the Renaissance? What theory does the author propose for why the Baroque evolved out of the Renaissance? How are the theoretical books and works of the Baroque different than the “treatises” of the Renaissance? Wölfflin, Heinrich. -

Architecture (ARCH) 1

Architecture (ARCH) 1 their architectural use. ARCH 504 Materials and Building Construction ARCHITECTURE (ARCH) II (3) This first-year graduate seminar course will continue to present students with information on fundamental and advanced building ARCH 501: Analysis of Architectural Precedents: Ancient Industrial materials and systems and on construction technologies associated with Revolution their architectural use. Students will also consider the advancements in architectural materials and technologies. It is the second part of 3 Credits a two-semester sequence preceded by ARCH 503. Recurrent course Analysis of architectural precendents from antiquity to the turn of the themes include 1) architecture as a product of culture (wisdom, abilities, twentieth century through methodologies emphasizing research and aspirations), 2) architecture as a product of place (materials, tools, critical inquiry. The 20th century Italian architectural historian and topography, climate), the relationship between architectural appearance theorist Manfredo Tafuri argued that architecture was intrinsically presented and the mode of construction employed, 3) materials and forward-looking and utopian: "project" in both the sense of "a design making as an expression of an idea and 4) the relationship of a building project" and a leap into the future, like "projectile" or "projection." However, whole to a detail. This course is motivated by these concerns: a firm he also argued that architectural history, understood deeply and critically, belief that architects -

Friedrichstrasse in Berlin and Central Street in Harbin As Examples1

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE HISTORICAL URBAN FABRIC provided by Siberian Federal University Digital Repository UDC 711 Wang Haoyu, Li Zhenyu College of Architecture and Urban Planning, Tongji University, China, Shanghai, Yangpu District, Siping Road 1239, 200092 e-mail: [email protected], [email protected] COMPARISON STUDY OF TYPICAL HISTORICAL STREET SPACE BETWEEN CHINA AND GERMANY: FRIEDRICHSTRASSE IN BERLIN AND CENTRAL STREET IN HARBIN AS EXAMPLES1 Abstract: The article analyses the similarities and the differences of typical historical street space and urban fabric in China and Germany, taking Friedrichstrasse in Berlin and Central Street in Harbin as examples. The analysis mainly starts from four aspects: geographical environment, developing history, urban space fabric and building style. The two cities have similar geographical latitudes but different climate. Both of the two cities have a long history of development. As historical streets, both of the two streets are the main shopping street in the two cities respectively. The Berlin one is a famous luxury-shopping street while the Harbin one is a famous shopping destination for both citizens and tourists. As for the urban fabric, both streets have fishbone-like spatial structure but with different densities; both streets are pedestrian-friendly but with different scales; both have courtyards space structure but in different forms. Friedrichstrasse was divided into two parts during the World War II and it was partly ruined. It was rebuilt in IBA in the 1980s and many architectural masterpieces were designed by such world-known architects like O.M. -

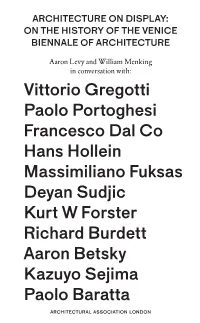

Architecture on Display: on the History of the Venice Biennale of Architecture

archITECTURE ON DIspLAY: ON THE HISTORY OF THE VENICE BIENNALE OF archITECTURE Aaron Levy and William Menking in conversation with: Vittorio Gregotti Paolo Portoghesi Francesco Dal Co Hans Hollein Massimiliano Fuksas Deyan Sudjic Kurt W Forster Richard Burdett Aaron Betsky Kazuyo Sejima Paolo Baratta archITECTUraL assOCIATION LONDON ArchITECTURE ON DIspLAY Architecture on Display: On the History of the Venice Biennale of Architecture ARCHITECTURAL ASSOCIATION LONDON Contents 7 Preface by Brett Steele 11 Introduction by Aaron Levy Interviews 21 Vittorio Gregotti 35 Paolo Portoghesi 49 Francesco Dal Co 65 Hans Hollein 79 Massimiliano Fuksas 93 Deyan Sudjic 105 Kurt W Forster 127 Richard Burdett 141 Aaron Betsky 165 Kazuyo Sejima 181 Paolo Baratta 203 Afterword by William Menking 5 Preface Brett Steele The Venice Biennale of Architecture is an integral part of contemporary architectural culture. And not only for its arrival, like clockwork, every 730 days (every other August) as the rolling index of curatorial (much more than material, social or spatial) instincts within the world of architecture. The biennale’s importance today lies in its vital dual presence as both register and infrastructure, recording the impulses that guide not only architec- ture but also the increasingly international audienc- es created by (and so often today, nearly subservient to) contemporary architectures of display. As the title of this elegant book suggests, ‘architecture on display’ is indeed the larger cultural condition serving as context for the popular success and 30- year evolution of this remarkable event. To look past its most prosaic features as an architectural gathering measured by crowd size and exhibitor prowess, the biennale has become something much more than merely a regularly scheduled (if at times unpredictably organised) survey of architectural experimentation: it is now the key global embodiment of the curatorial bias of not only contemporary culture but also architectural life, or at least of how we imagine, represent and display that life. -

Six Canonical Projects by Rem Koolhaas

5 Six Canonical Projects by Rem Koolhaas has been part of the international avant-garde since the nineteen-seventies and has been named the Pritzker Rem Koolhaas Architecture Prize for the year 2000. This book, which builds on six canonical projects, traces the discursive practice analyse behind the design methods used by Koolhaas and his office + OMA. It uncovers recurring key themes—such as wall, void, tur montage, trajectory, infrastructure, and shape—that have tek structured this design discourse over the span of Koolhaas’s Essays on the History of Ideas oeuvre. The book moves beyond the six core pieces, as well: It explores how these identified thematic design principles archi manifest in other works by Koolhaas as both practical re- Ingrid Böck applications and further elaborations. In addition to Koolhaas’s individual genius, these textual and material layers are accounted for shaping the very context of his work’s relevance. By comparing the design principles with relevant concepts from the architectural Zeitgeist in which OMA has operated, the study moves beyond its specific subject—Rem Koolhaas—and provides novel insight into the broader history of architectural ideas. Ingrid Böck is a researcher at the Institute of Architectural Theory, Art History and Cultural Studies at the Graz Ingrid Böck University of Technology, Austria. “Despite the prominence and notoriety of Rem Koolhaas … there is not a single piece of scholarly writing coming close to the … length, to the intensity, or to the methodological rigor found in the manuscript -

React/Review | Volume 1 13

react/review | volume 1 13 Outside of Architecture: Between Mediating and Navigating the Air Katarzyna Balug Air is the physical connection between us and our environment, transmitting our sense experience of light, heat, sound, taste, smell and pressure. But its very transparency prevents us from observing its continuous transformations. Atmosfields and pneumatic environments aim to reveal the aesthetic of air, both in the natural states which make up the atmosphere and by using thin membranes to manifest their motions and forces, in order to extend and change our direct experience of air and our relation to our atmospheric environment. – Graham Stevens1 Reveal, make manifest, extend, and relate: English artist Graham Stevens was uniquely articulate in capturing, in words and structures, the capacity of the inflatable form to condition the human’s relationship with her environment. Throughout 1960s Western Europe and the United States, young architects and artists like Stevens adopted the materials and aesthetics of the lunar Space Race to create immersive air-filled environments especially attuned to Earth. However, there was a significant difference in the operating logics of space structures and the Earth-bound forms they informed. While the pursuit of spaceflight had, since the mid-nineteenth century, emphasized the keeping out of the environment and the production of an artificial, fully controlled and enclosed atmosphere, inflatable architectures invited the outside in. These forms continually registered and mediated the relationship 1 Graham Stevens, “Pneumatics and Atmospheres,” Architectural Digest, no. 3 (1972): 166. react/review | volume 1 51 between circulating air and the plastic membrane, which together formed a structure without rigidity, and the body that occupied the resulting space.