Suppression of Resistance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Unified Concept of Population Transfer

Denver Journal of International Law & Policy Volume 21 Number 1 Fall Article 4 May 2020 A Unified Concept of opulationP Transfer Christopher M. Goebel Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/djilp Recommended Citation Christopher M. Goebel, A Unified Concept of Population Transfer, 21 Denv. J. Int'l L. & Pol'y 29 (1992). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Denver Journal of International Law & Policy by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. A Unified Concept of Population Transfer CHRISTOPHER M. GOEBEL* Population transfer is an issue arising often in areas of ethnic ten- sion, from Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina to the Western Sahara, Tibet, Cyprus, and beyond. There are two forms of human population transfer: removals and settlements. Generally, commentators in interna- tional law have yet to discuss the two together as a single category of population transfer. In discussing the prospects for such a broad treat- ment, this article is a first to compare and contrast international law's application to removals and settlements. I. INTRODUCTION International attention is focusing on uprooted people, especially where there are tensions of ethnic proportions. The Red Cross spent a significant proportion of its budget aiding what it called "displaced peo- ple," removed en masse from their abodes. Ethnic cleansing, a term used by the Serbs, was a process of population transfer aimed at removing the non-Serbian population from large areas of Bosnia-Herzegovina.2 The large-scale Jewish settlements into the Israeli-occupied Arab territories continue to receive publicity. -

P3 2.E$S Layout 1

WEDNESDAY, MAY 20, 2015 LOCAL Fugitives, one sentenced to life, arrested in Jahra KUWAIT: Jahra detectives arrested three persons wanted on multiple charges. They include Bader K, Syrian and sen- tenced to five years in jail, Mutlaq A, Kuwaiti and sentenced to five years, and Hussein K, Bedoon (stateless) and sen- tenced to 90 years in jail, or life in prison. The third suspect was arrested inside his house during a police raid. The three were sent to concerned authorities. Gas station burglar caught Meanwhile, Mubarak Al-Kabeer detectives arrested a Kuwaiti man accused of committing a robbery at a gas sta- tion in Adan earlier. The suspect reportedly drove a car that did not carry any license plates. The suspect works for the same company that owns the station he robbed, the Interior Ministry said in a statement. He was sent to con- cerned authorities. Traffic campaign Separately, Hawally police carried out a traffic campaign that resulted in issuing 580 tickets, impounding 55 cars and arresting three persons on different charges. The Adan gas station robbery suspect. The suspects Bader K, Mutlaq A and Hussein K pictured in these handout photos. Crime Report KDF demands releasing detained activists By A Saleh being investigated by the interior ministry. In a statement KMA issued after a doctor KUWAIT: Kuwait Democratic Forum’s (KDF) was accused of causing the death of a Secretary General Bandar Al-Khairan called female citizen he operated on, KMA for issuing a pardon to all those who had Secretary General Dr Mohammed Al-Qenae been prosecuted during a period when stressed that reports about the woman’s “political situations were not favorable”. -

Mass Displacement in Post-Catastrophic Societies: Vulnerability, Learning, and Adaptation in Germany and India, 1945–1952

Futures That Internal Migration Place-Specifi c Introduction Never Were and the Left Material Resources MASS DISPLACEMENT IN POST-CATASTROPHIC SOCIETIES: VULNERABILITY, LEARNING, AND ADAPTATION IN GERMANY AND INDIA, 1945–1952 Avi Sharma The summer of 1945 in Germany was exceptional. Displaced persons (UN DPs), refugees, returnees, ethnic German expellees (Vertriebene)1 and soldiers arrived in desperate need of care, including food, shelter, medical attention, clothing, bedding, shoes, cooking utensils, and cooking fuel. An estimated 7.3 million people transited to or through Berlin between July 1945 and March 1946.2 In part because of its geographical location, Berlin was an extreme case, with observers estimating as many as 30,000 new arrivals per day. However, cities across Germany were swollen with displaced persons, starved of es- sential supplies, and faced with catastrophic housing shortages. During that time, ethnic, religious, and linguistic “others” were frequently conferred legal privileges, while ethnic German expellees and internally displaced persons (IDPs) were disadvantaged by the occupying forces. How did refugees, returnees, DPs, IDPs and other migrants navigate the fractured governmentality and allocated scar- city of the postwar regime? How did survivors survive the postwar? The summer of 1947 in South Asia was extraordinary in diff erent ways.3 Faced with a hastily organized division of the Indian sub- continent into India and Pakistan (known as the Partition), between 10 and 14 million Muslims, Sikhs, and Hindus crossed borders in a period of only a few months. Estimates put the one-day totals for 2 Angelika Königseder, cross-border movement as high as 400,000, and data on mortality Flucht nach Berlin: Jüdische Displaced Persons 1945– 4 range between 200,000 and 2 million people killed. -

Gulf Affairs

Autumn 2016 A Publication based at St Antony’s College Identity & Culture in the 21st Century Gulf Featuring H.E. Salah bin Ghanem Al Ali Minister of Culture and Sports State of Qatar H.E. Shaikha Mai Al-Khalifa President Bahrain Authority for Culture & Antiquities Ali Al-Youha Secretary General Kuwait National Council for Culture, Arts and Letters Nada Al Hassan Chief of Arab States Unit UNESCO Foreword by Abdulaziz Saud Al-Babtain OxGAPS | Oxford Gulf & Arabian Peninsula Studies Forum OxGAPS is a University of Oxford platform based at St Antony’s College promoting interdisciplinary research and dialogue on the pressing issues facing the region. Senior Member: Dr. Eugene Rogan Committee: Chairman & Managing Editor: Suliman Al-Atiqi Vice Chairman & Partnerships: Adel Hamaizia Editor: Jamie Etheridge Chief Copy Editor: Jack Hoover Arabic Content Lead: Lolwah Al-Khater Head of Outreach: Mohammed Al-Dubayan Communications Manager: Aisha Fakhroo Broadcasting & Archiving Officer: Oliver Ramsay Gray Research Assistant: Matthew Greene Copyright © 2016 OxGAPS Forum All rights reserved Autumn 2016 Gulf Affairs is an independent, non-partisan journal organized by OxGAPS, with the aim of bridging the voices of scholars, practitioners, and policy-makers to further knowledge and dialogue on pressing issues, challenges and opportunities facing the six member states of the Gulf Cooperation Council. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessar- ily represent those of OxGAPS, St Antony’s College, or the University of Oxford. Contact Details: OxGAPS Forum 62 Woodstock Road Oxford, OX2 6JF, UK Fax: +44 (0)1865 595770 Email: [email protected] Web: www.oxgaps.org Design and Layout by B’s Graphic Communication. -

To View Online Click Here

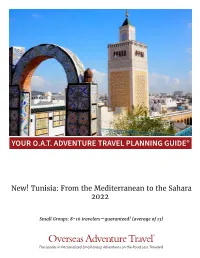

YOUR O.A.T. ADVENTURE TRAVEL PLANNING GUIDE® New! Tunisia: From the Mediterranean to the Sahara 2022 Small Groups: 8-16 travelers—guaranteed! (average of 13) Overseas Adventure Travel ® The Leader in Personalized Small Group Adventures on the Road Less Traveled 1 Dear Traveler, At last, the world is opening up again for curious travel lovers like you and me. And the O.A.T. New! Tunisia: From the Mediterranean to the Sahara itinerary you’ve expressed interest in will be a wonderful way to resume the discoveries that bring us so much joy. You might soon be enjoying standout moments like these: Venture out to the Tataouine villages of Chenini and Ksar Hedada. In Chenini, your small group will interact with locals and explore the series of rock and mud-brick houses that are seemingly etched into the honey-hued hills. After sitting down for lunch in a local restaurant, you’ll experience Ksar Hedada, where you’ll continue your people-to-people discoveries as you visit a local market and meet local residents. You’ll also meet with a local activist at a coffee shop in Tunis’ main medina to discuss social issues facing their community. You’ll get a personal perspective on these issues that only a local can offer. The way we see it, you’ve come a long way to experience the true culture—not some fairytale version of it. So we keep our groups small, with only 8-16 travelers (average 13) to ensure that your encounters with local people are as intimate and authentic as possible. -

Forced Population Transfers Resolve Self-Determination Conflicts?

Can Forced Population Transfers Resolve Self-determination Conflicts? A European Perspective Stefan Wolff Department of European Studies University of Bath Bath BA2 7AY England, UK [email protected] Introduction Self-determination conflicts are among the most violent forms of civil wars that can engulf modern societies. As they are in most cases linked to claims of ethnic, religious, linguistic or otherwise defined groups for secession from, or for political domination in, an existing state they also have repercussions on regional and international stability. Self-determination conflicts can be observed on all continents. Not all of them are violent, but most have a clear potential for violent escalation and are therefore an important concern for international and regional governmental organisations seeking to preserve peace and stability. However, the capacity of organisations like the UN, the OSCE and the EU to do so has only gradually developed over the past decade and is still a far cry from being sufficient. In the past and present, states (and population groups within them) have therefore felt that they had been and are left to their own devices when it comes to preserving their internal stability and external security. The largely incongruent political and ethnic maps of Europe have meant that self- determination conflicts on this continent have mostly taken the form of ethnic conflicts: from Northern Ireland to the Caucasus, from the Basque country to the Åland islands and from Kosovo to Silesia the competing claims of distinct ethnic groups to self-determination have been the most prominent sources of conflicts within and across state boundaries. -

Indicators for Monitoring the Un Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples

INDICATORS FOR MONITORING THE UN DECLARATION ON THE RIGHTS OF INDIGENOUS PEOPLES A solid framework and a practical tool for assessing the implementation of UNDRIP’s provisions. The indicators serve to detect gaps in implementation, hold duty-bearers accountable, and devise implementation strategies. 1 WHAT IS THE INDIGENOUS NAVIGATOR? The Indigenous Navigator comprises a set of tools for monitoring indigenous peoples’ rights and development. One of these tools is a set of indicators, which serve to pinpoint what to look for when measuring whether the provisions of UNDRIP are implemented in a given community or country. The indicators are structured around 13 thematic domains reflected in UNDRIP and have been systematically developed with a solid foundation in the OHCHR’s methodology for developing human rights indicators.1 Like all other human rights instruments, UNDRIP comprises standards on specific rights and cross-cutting human rights norms. The first step towards identifying the indicators has therefore been to identify the attributes – or building blocks – contained in UNDRIP. Subsequently, measurable indicators have been identified with a view to capturing States’ duties to respect, protect and fulfil indigenous peoples’ human rights. The indicators framework comprises: Structural indicators, which assess the legal and policy framework of a given country. Process indicators, which measure the states’ ongoing efforts to implement human rights commitments through programs, budget allocations, etc. Outcome indicators, which capture the actual enjoyment of human rights by indigenous peoples. The indicators can also be used to measure essential aspects of the SDGs as well as the commitments made by States at the 2014 World Conference on Indigenous Peoples. -

The Cultural Heritage of Indigenous Peoples and Its Protection: Rights and Challenges

The cultural heritage of indigenous peoples and its protection: rights and challenges Based on presentations of the International Expert Seminar of the Saami Cultural Heritage Week, organized by the Saami Council in Rovaniemi, October 27•28, 2008. Contents 1 Cultural heritage 1 1.2 Misappropriation of the cultural heritage of indigenous peoples 2 1.3 How to protect the cultural heritage of indigenous peoples? 3 1.3.1 Self•determination and free, prior and informed consent 4 2 General UN instruments relevant for the cultural heritage of indigenous peoples 5 2.1 The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights 5 2.2 The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights 6 2.3 The Universal Declaration on Human Rights 6 2.4 The Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Racial Discrimination 6 3 The UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples 7 3.1 Non•discrimination 7 3.2 Self•determination 8 3.3 Indigenous peoples have to be seen as indigenous 9 3.4 Indigenous peoples and land rights 9 3.5 Culture 10 3.6 Recognition of indigenous peoples’ own institutions 11 3.7 Procedures 12 4 Other relevant international organizations and instruments 13 4.1 The World Intellectual Property Organization 13 4.1.1 The Intergovernmental Committee on Intellectual Property, Genetic Resources, Traditional Knowledge and Folklore 13 4.2 The ILO Convention No. 169 14 4.3 UNESCO 15 4.3.1 The Declaration on Cultural Diversity 16 4.3.2 The Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions 17 4.4 The Convention on Biological Diversity 17 4.5 The American Declaration of the Rights and Duties of Man 19 5 Suggestions and best practices 19 5.1 Review of the draft principles and guidelines on the heritage of indigenous peoples 21 References 22 This document is based on the material from the International Expert Seminar of the Saami Cultural Heritage Week organized by the Saami Council in Rovaniemi October 27•28, 2008. -

German’ Communities from Eastern Europe at the End of the Second World War

EUROPEAN UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE, FLORENCE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY AND CIVILIZATION EUI Working Paper HEC No. 2004/1 The Expulsion of the ‘German’ Communities from Eastern Europe at the End of the Second World War Edited by STEFFEN PRAUSER and ARFON REES BADIA FIESOLANA, SAN DOMENICO (FI) All rights reserved. No part of this paper may be reproduced in any form without permission of the author(s). © 2004 Steffen Prauser and Arfon Rees and individual authors Published in Italy December 2004 European University Institute Badia Fiesolana I – 50016 San Domenico (FI) Italy www.iue.it Contents Introduction: Steffen Prauser and Arfon Rees 1 Chapter 1: Piotr Pykel: The Expulsion of the Germans from Czechoslovakia 11 Chapter 2: Tomasz Kamusella: The Expulsion of the Population Categorized as ‘Germans' from the Post-1945 Poland 21 Chapter 3: Balázs Apor: The Expulsion of the German Speaking Population from Hungary 33 Chapter 4: Stanislav Sretenovic and Steffen Prauser: The “Expulsion” of the German Speaking Minority from Yugoslavia 47 Chapter 5: Markus Wien: The Germans in Romania – the Ambiguous Fate of a Minority 59 Chapter 6: Tillmann Tegeler: The Expulsion of the German Speakers from the Baltic Countries 71 Chapter 7: Luigi Cajani: School History Textbooks and Forced Population Displacements in Europe after the Second World War 81 Bibliography 91 EUI WP HEC 2004/1 Notes on the Contributors BALÁZS APOR, STEFFEN PRAUSER, PIOTR PYKEL, STANISLAV SRETENOVIC and MARKUS WIEN are researchers in the Department of History and Civilization, European University Institute, Florence. TILLMANN TEGELER is a postgraduate at Osteuropa-Institut Munich, Germany. Dr TOMASZ KAMUSELLA, is a lecturer in modern European history at Opole University, Opole, Poland. -

Sharjah Art Foundation Announces the Late Okwui Enwezor As Curator of Sharjah Biennial 15

For Immediate Release 4 November 2019 Hoor Al Qasimi (left). Photo: Sebastian Böttcher; Okwui Enwezor (right). Photo: Chika Okeke-Agulu Sharjah Art Foundation Announces the Late Okwui Enwezor as Curator of Sharjah Biennial 15 Foundation Director Hoor Al Qasimi to Co-Curate Alongside Working Group Members Tarek Abou El Fetouh, Ute Meta Bauer, Salah M. Hassan and Chika Okeke-Agulu, with the Support of an Advisory Committee Including David Adjaye, John Akomfrah and Christine Tohme SB15 Opens March 2021 in Sharjah, United Arab Emirates Sharjah Art Foundation (SAF) in Sharjah, UAE, today announced the renowned critic and curator Okwui Enwezor (1963–2019) as curator of the next Sharjah Biennial, opening in March 2021. Enwezor conceived the 15th edition of the Sharjah Biennial (SB15), entitled Thinking Historically in the Present, as a platform to reflect on the past fourteen editions of the Biennial and to consider the future of the biennial model. In accordance with Enwezor’s wishes, SB15 will be realized with the support of Sharjah Art Foundation Director Hoor Al Qasimi as co-curator alongside a working group of Enwezor’s longtime collaborators: curator Tarek Abou El Fetouh; professor and Founding Director of NTU CCA Singapore Ute Meta Bauer; art historian and Cornell University professor Salah M. Hassan; and art historian and Princeton University professor Chika Okeke-Agulu. Al Qasimi and the SB15 Working Group will oversee the development and implementation of Enwezor’s curatorial concept in collaboration with an advisory committee composed of architect Sir David Adjaye, artist John Akomfrah and Ashkal Alwan Director Christine Tohme, who will provide additional consultation on the Biennial. -

An Inside Look Into Hygiene Education Facilities Completed

COUNTRY: IRAQ Report: March-June 2013 Category: Water and Sanitation Hygiene (WASH)/Sustainability/Hygiene Education/Culture http://www.jen-npo.org/en/contribute Hygiene Education training sessions, and have expressed their admiration and satisfaction of JEN’s work and materials. We would like to thank all our supporters who have made our education programs possible in schools throughout Iraq. WASH Facilities Completed: School Gives Thanks Diala Province’s Om Salma Intermediate School for Girls restroom facilities have been refurbished. Previously the school’s facilities were in unusable and unsanitary conditions. Without proper functioning restrooms, the school could not operate functionally. The headmaster of the girl’s school had previously gone to the Iraqi Department of Education numerous times Above: Girls at the Om Sama Intermediate School listen intently to the requesting repairs, but to no avail, they denied their lectures on proper hygiene and care. requests. JEN received permission from both the Department and Ministry of Education to fund and An Inside Look into Hygiene Education perform the renovations themselves. With dedication and hard work, the new bathrooms have been completed Our hygiene programs, teaching proper practices to and the school is now completely operational. JEN students, have started this March. Security has proven conducted student and teacher trainings about hygiene to be difficult, with many road blockages, especially in education, as well as how to keep their newly the Anbar and Diala provinces, JEN hygiene promoters refurbished restroom clean to ensure its longevity. and engineers cannot always reach our partner schools. School administrators gave their thanks in addition to a The ten-year anniversary of the US-led invasion took surprise song and dance for JEN staff performed by the place on March 19th, where over 60 people were killed in schoolgirls. -

Indigenous Peoples' Rights in Constitutions Assessment Tool

Indigenous Peoples’ Rights in Constitutions Assessment Tool Indigenous Peoples’ Rights in Constitutions Assessment Tool Amanda Cats-Baril © 2020 International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance International IDEA Strömsborg SE–103 34 Stockholm Sweden Tel: +46 8 698 37 00 Email: [email protected] Website: <https://www.idea.int> The electronic version of this publication, except the images, is available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0) licence. You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the publication as well as to remix and adapt it provided it is only for non- commercial purposes, that you appropriately attribute the publication, and that you distribute it under an identical licence. For more information on this licence see http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/. International IDEA publications are independent of specific national or political interests. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent the views of International IDEA, its Board or its Council members. Graphic and cover design: Richard van Rooijen (based on a concept developed by KSB Design) Cover image and artwork: Ancestors © Sarrita King Sarrita’s Ancestors paintings are layered with dots. Markings made on the land over thousands of years can be seen entangled with patterns covering the land today, such as sand hills, flora and paths made by humans and animals. Beneath the land are the waterways which have been virtually constant over time feeding the land, the flora, fauna and humans. These are the same waterways that supplied our ancestors which are now one with the land.