Colonization by Chironomidae \(Insecta, Diptera\) on Three Distinct

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The 2014 Golden Gate National Parks Bioblitz - Data Management and the Event Species List Achieving a Quality Dataset from a Large Scale Event

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Stewardship and Science The 2014 Golden Gate National Parks BioBlitz - Data Management and the Event Species List Achieving a Quality Dataset from a Large Scale Event Natural Resource Report NPS/GOGA/NRR—2016/1147 ON THIS PAGE Photograph of BioBlitz participants conducting data entry into iNaturalist. Photograph courtesy of the National Park Service. ON THE COVER Photograph of BioBlitz participants collecting aquatic species data in the Presidio of San Francisco. Photograph courtesy of National Park Service. The 2014 Golden Gate National Parks BioBlitz - Data Management and the Event Species List Achieving a Quality Dataset from a Large Scale Event Natural Resource Report NPS/GOGA/NRR—2016/1147 Elizabeth Edson1, Michelle O’Herron1, Alison Forrestel2, Daniel George3 1Golden Gate Parks Conservancy Building 201 Fort Mason San Francisco, CA 94129 2National Park Service. Golden Gate National Recreation Area Fort Cronkhite, Bldg. 1061 Sausalito, CA 94965 3National Park Service. San Francisco Bay Area Network Inventory & Monitoring Program Manager Fort Cronkhite, Bldg. 1063 Sausalito, CA 94965 March 2016 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science office in Fort Collins, Colorado, publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics. These reports are of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Report Series is used to disseminate comprehensive information and analysis about natural resources and related topics concerning lands managed by the National Park Service. -

The Aquatic Insect Community in Penitentiary Glen, a Portage Escarpment Stream in Northeastern Ohio1

Copyright © 1984 Ohio Acad. Sci. 0030-0950/84/0003-0113 $2.00/0 THE AQUATIC INSECT COMMUNITY IN PENITENTIARY GLEN, A PORTAGE ESCARPMENT STREAM IN NORTHEASTERN OHIO1 DAVID J. ROBERTSON,2 Department of Biological Sciences, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA 15260 ABSTRACT. The aquatic insects inhabiting Penitentiary Glen, an isolated, high- gradient lotic habitat along Stoney Brook in Lake County, Ohio, were sampled during winter (December 1976), spring (May 1977), and summer (July 1977) months. Col- lections of immatures from dip nets and Surber samples were augmented with adult specimens taken in sweep nets and hand-picked from streamside rocks. Seventy-three species distributed among 60 genera in 7 orders were collected. Based on the diverse composition of the community dominated by organisms intolerant of organic en- richment, water quality in Stoney Brook is not significantly degraded. Community composition varies seasonally, with a trend toward a declining proportion of facultative organisms and increasing proportions of saproxenous and saprophobic organisms from winter through spring and into summer. Benthic diversity in Penitentiary Glen compares favorably with that in similar, relatively undisturbed northeastern Ohio streams, but the identity and proportional distribution of aquatic taxa varies considerably between streams. OHIO J. SCI. 84 (3): 113-119, 1984 INTRODUCTION the base to over 300 m at the crest. The Portage Escarpment demarks the Streams draining the highlands have exca- northern edge of the Allegheny Plateau in vated narrow gorges into the edge of the northeastern Ohio. A steep ridge paral- plateau in their descent to Lake Erie. Be- leling the southern shoreline of Lake Erie tween the Grand River and its tributaries reveals the location of the escarpment on the northeast and the Cuyahoga Valley which extends westward from Ashtabula on the west, the streams have created a Co. -

(Insecta: Diptera) Assemblages Along an Andean Altitudinal Gradient

Vol. 20: 169–184, 2014 AQUATIC BIOLOGY Published online April 9 doi: 10.3354/ab00554 Aquat Biol Chironomid (Insecta: Diptera) assemblages along an Andean altitudinal gradient Erica E. Scheibler1,*, Sergio A. Roig-Juñent1, M. Cristina Claps2 1IADIZA, CCT CONICET Mendoza. Avda. Ruiz Leal s/n. Parque Gral. San Martín, CC 507, 5500 Mendoza, Argentina 2ILPLA, CCT CONICET La Plata, Boulevard 120 y 62 1900 La Plata, Argentina ABSTRACT: Chironomidae are an abundant, diverse and ecologically important group common in mountain streams worldwide, but their patterns of distribution have been poorly described for the Andes region in western-central Argentina. Here we examine chironomid assemblages along an altitudinal gradient in the Mendoza River basin to study how spatial and seasonal variations affect the abundance patterns of genera across a gradient of elevation, assess the effects of envi- ronmental variables on the chironomid community and to describe its diversity using rarefaction and Shannon’s indices. Three replicate samples and physicochemical parameters were measured seasonally at 11 sites in 2000 and 2001. Twelve genera of chironomid larvae were identified, which belonged to 5 subfamilies. Chironomid composition changed from the headwaters to the outlet and was associated with changes in altitude, water temperature, substrate size and conduc- tivity. We found a pronounced seasonal and spatial variation in the macroinvertebrate community and in physicochemical parameters. Environmental conditions such as elevated conductivity levels and increased river discharge occurring during the summer produced low chironomid density values at the sampling sites. The rarefaction index revealed that the sampling sites with highest richness were LU (middle section of the river) and PO (lower section). -

Chironomidae Hirschkopf

Literatur Chironomidae Gesäuse U.A. zur Bestimmung und Ermittlung der Autökologie herangezogene Literatur: Albu, P. (1972): Două specii de Chironomide noi pentru ştiinţă în masivul Retezat.- St. şi Cerc. Biol., Seria Zoologie, 24: 15-20. Andersen, T.; Mendes, H.F. (2002): Neotropical and Mexican Mesosmittia Brundin, with the description of four new species (Insecta, Diptera, Chironomidae).- Spixiana, 25(2): 141-155. Andersen, T.; Sæther, O.A. (1993): Lerheimia, a new genus of Orthocladiinae from Africa (Diptera: Chironomidae).- Spixiana, 16: 105-112. Andersen, T.; Sæther, O.A.; Mendes, H.F. (2010): Neotropical Allocladius Kieffer, 1913 and Pseudosmittia Edwards, 1932 (Diptera: Chironomidae).- Zootaxa, 2472: 1-77. Baranov, V.A. (2011): New and rare species of Orthocladiinae (Diptera, Chironomidae) from the Crimea, Ukraine.- Vestnik zoologii, 45(5): 405-410. Boggero, A.; Zaupa, S.; Rossaro, B. (2014): Pseudosmittia fabioi sp. n., a new species from Sardinia (Diptera: Chironomidae, Orthocladiinae).- Journal of Entomological and Acarological Research, [S.l.],46(1): 1-5. Brundin, L. (1947): Zur Kenntnis der schwedischen Chironomiden.- Arkiv för Zoologi, 39 A(3): 1- 95. Brundin, L. (1956): Zur Systematik der Orthocladiinae (Dipt. Chironomidae).- Rep. Inst. Freshwat. Drottningholm 37: 5-185. Casas, J.J.; Laville, H. (1990): Micropsectra seguyi, n. sp. du groupe attenuata Reiss (Diptera: Chironomidae) de la Sierra Nevada (Espagne).- Annls Soc. ent. Fr. (N.S.), 26(3): 421-425. Caspers, N. (1983): Chironomiden-Emergenz zweier Lunzer Bäche, 1972.- Arch. Hydrobiol. Suppl. 65: 484-549. Caspers, N. (1987): Chaetocladius insolitus sp. n. (Diptera: Chironomidae) from Lunz, Austria. In: Saether, O.A. (Ed.): A conspectus of contemporary studies in Chironomidae (Diptera). -

Checklist of the Family Chironomidae (Diptera) of Finland

A peer-reviewed open-access journal ZooKeys 441: 63–90 (2014)Checklist of the family Chironomidae (Diptera) of Finland 63 doi: 10.3897/zookeys.441.7461 CHECKLIST www.zookeys.org Launched to accelerate biodiversity research Checklist of the family Chironomidae (Diptera) of Finland Lauri Paasivirta1 1 Ruuhikoskenkatu 17 B 5, FI-24240 Salo, Finland Corresponding author: Lauri Paasivirta ([email protected]) Academic editor: J. Kahanpää | Received 10 March 2014 | Accepted 26 August 2014 | Published 19 September 2014 http://zoobank.org/F3343ED1-AE2C-43B4-9BA1-029B5EC32763 Citation: Paasivirta L (2014) Checklist of the family Chironomidae (Diptera) of Finland. In: Kahanpää J, Salmela J (Eds) Checklist of the Diptera of Finland. ZooKeys 441: 63–90. doi: 10.3897/zookeys.441.7461 Abstract A checklist of the family Chironomidae (Diptera) recorded from Finland is presented. Keywords Finland, Chironomidae, species list, biodiversity, faunistics Introduction There are supposedly at least 15 000 species of chironomid midges in the world (Armitage et al. 1995, but see Pape et al. 2011) making it the largest family among the aquatic insects. The European chironomid fauna consists of 1262 species (Sæther and Spies 2013). In Finland, 780 species can be found, of which 37 are still undescribed (Paasivirta 2012). The species checklist written by B. Lindeberg on 23.10.1979 (Hackman 1980) included 409 chironomid species. Twenty of those species have been removed from the checklist due to various reasons. The total number of species increased in the 1980s to 570, mainly due to the identification work by me and J. Tuiskunen (Bergman and Jansson 1983, Tuiskunen and Lindeberg 1986). -

Volume 2, Chapter 12-19: Terrestrial Insects: Holometabola-Diptera

Glime, J. M. 2017. Terrestrial Insects: Holometabola – Diptera Nematocera 2. In: Glime, J. M. Bryophyte Ecology. Volume 2. 12-19-1 Interactions. Ebook sponsored by Michigan Technological University and the International Association of Bryologists. eBook last updated 19 July 2020 and available at <http://digitalcommons.mtu.edu/bryophyte-ecology2/>. CHAPTER 12-19 TERRESTRIAL INSECTS: HOLOMETABOLA – DIPTERA NEMATOCERA 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Cecidomyiidae – Gall Midges ........................................................................................................................ 12-19-2 Mycetophilidae – Fungus Gnats ..................................................................................................................... 12-19-3 Sciaridae – Dark-winged Fungus Gnats ......................................................................................................... 12-19-4 Ceratopogonidae – Biting Midges .................................................................................................................. 12-19-6 Chironomidae – Midges ................................................................................................................................. 12-19-9 Belgica .................................................................................................................................................. 12-19-14 Culicidae – Mosquitoes ................................................................................................................................ 12-19-15 Simuliidae – Blackflies -

2 3 Influence of Invasive Palms on Terrestrial Arthropod Assemblages 4

1 1 2011. Biological Conservation 144: 518-525 2 http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0006320710004404 3 4 Influence of invasive palms on terrestrial arthropod assemblages 5 in desert spring habitat 6 7 Jeffrey G. Holmquista,1,*, Jutta Schmidt-Gengenbacha,1, Michèle R. Slatonb,2 8 9 aUniversity of California San Diego, White Mountain Research Station, 3000 East Line 10 Street, Bishop, California, USA 93514 11 bDeath Valley National Park, Death Valley, California, USA 92328 12 13 *Corresponding author [email protected] 14 15 1current: University of California Los Angeles, Institute of the Environment and 16 Sustainability, White Mountain Research Center, 3000 East Line Street, Bishop, California, 17 USA 93514 18 2current: Inyo National Forest, 351 Pacu Lane, Suite 200, Bishop, California, USA 93514 19 20 21 22 23 2 1 ABSTRACT 2 Invasive plants can eliminate native flora and ultimately have negative indirect effects on 3 fauna and the functional ecology of ecosystems, but understanding of these cascading effects 4 on arthropod assemblages is poor. Desert spring habitats are small, isolated landscape 5 elements that are literal oases for flora and fauna and support high diversity assemblages; 6 invasive palms can colonize desert springs and form monocultures. In an effort to understand 7 effects of these invasive trees on higher terrestrial trophic levels at springs, we contrasted 8 assemblage structure of terrestrial arthropods in native vegetation versus invasive palm 9 habitat. We sampled arthropods in paired palm and native habitat at ten springs in Death 10 Valley National Park, California, USA, during both spring and fall growing seasons using 11 suction sampling. -

Biological Assessment of the Patapsco River Tributary Watersheds, Howard County, Maryland

Biological Assessment of the Patapsco River Tributary Watersheds, Howard County, Maryland Spring 2003 Index Period and Summary of Round One County- Wide Assessment Patuxtent River April, 2005 Final Report UT to Patuxtent River Biological Assessment of the Patapsco River Tributary Watersheds, Howard County, Maryland Spring 2003 Index Period and Summary of Round One County-wide Assessment Prepared for: Howard County, Maryland Department of Public Works Stormwater Management Division 6751 Columbia Gateway Dr., Ste. 514 Columbia, MD 21046-3143 Prepared by: Tetra Tech, Inc. 400 Red Brook Blvd., Ste. 200 Owings Mills, MD 21117 Acknowledgement The principal authors of this report are Kristen L. Pavlik and James B. Stribling, both of Tetra Tech. They were also assisted by Erik W. Leppo. This document reports results from three of the six subwatersheds sampled during the Spring Index Period of the third year of biomonitoring by the Howard County Stormwater Management Division. Fieldwork was conducted by Tetra Tech staff including Kristen Pavlik, Colin Hill, David Bressler, Jennifer Pitt, and Amanda Richardson. All laboratory sample processing was conducted by Carolina Gallardo, Shabaan Fundi, Curt Kleinsorg, Chad Bogues, Joey Rizzo, Elizabeth Yarborough, Jessica Garrish, Chris Hines, and Sara Waddell. Taxonomic identification was completed by Dr. R. Deedee Kathman and Todd Askegaard; Aquatic Resources Center (ARC). Hunt Loftin, Linda Shook, and Brenda Decker (Tetra Tech) assisted with budget tracking and clerical support. This work was completed under the Howard County Purchase Order L 5305 to Tetra Tech, Inc. The enthusiasm and interest of the staff in the Stormwater Management Division, including Howard Saltzman and Angela Morales is acknowledged and appreciated. -

This Table Contains a Taxonomic List of Benthic Invertebrates Collected from Streams in the Upper Mississippi River Basin Study

This table contains a taxonomic list of benthic invertebrates collected from streams in the Upper Mississippi River Basin study unit as part of the USGS National Water Quality Assessemnt (NAWQA) Program. Invertebrates were collected from woody snags in selected streams from 1996-2004. Data Retreival occurred 26-JAN-06 11.10.25 AM from the USGS data warehouse (Taxonomic List Invert http://water.usgs.gov/nawqa/data). The data warehouse currently contains invertebrate data through 09/30/2002. Invertebrate taxa can include provisional and conditional identifications. For more information about invertebrate sample processing and taxonomic standards see, "Methods of analysis by the U.S. Geological Survey National Water Quality Laboratory -- Processing, taxonomy, and quality control of benthic macroinvertebrate samples", at << http://nwql.usgs.gov/Public/pubs/OFR00-212.html >>. Data Retrieval Precaution: Extreme caution must be exercised when comparing taxonomic lists generated using different search criteria. This is because the number of samples represented by each taxa list will vary depending on the geographic criteria selected for the retrievals. In addition, species lists retrieved at different times using the same criteria may differ because: (1) the taxonomic nomenclature (names) were updated, and/or (2) new samples containing new taxa may Phylum Class Order Family Subfamily Tribe Genus Species Taxon Porifera Porifera Cnidaria Hydrozoa Hydroida Hydridae Hydridae Cnidaria Hydrozoa Hydroida Hydridae Hydra Hydra sp. Platyhelminthes Turbellaria Turbellaria Nematoda Nematoda Bryozoa Bryozoa Mollusca Gastropoda Gastropoda Mollusca Gastropoda Mesogastropoda Mesogastropoda Mollusca Gastropoda Mesogastropoda Viviparidae Campeloma Campeloma sp. Mollusca Gastropoda Mesogastropoda Viviparidae Viviparus Viviparus sp. Mollusca Gastropoda Mesogastropoda Hydrobiidae Hydrobiidae Mollusca Gastropoda Basommatophora Ancylidae Ancylidae Mollusca Gastropoda Basommatophora Ancylidae Ferrissia Ferrissia sp. -

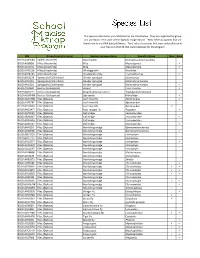

Species List

The species collected in your Malaise trap are listed below. They are organized by group and are listed in the order of the 'Species Image Library'. ‘New’ refers to species that are brand new to our DNA barcode library. 'Rare' refers to species that were only collected in your trap out of all 68 that were deployed for the program. BIN Group (scientific name) Species Common Name Scientific Name New Rare BOLD:AAA9584 Spiders (Araneae) Dwarf spider Dismodicus decemoculatus BOLD:ACI8838 Mites (Arachnida) Mite Mesostigmata BOLD:ACJ2455 Mites (Arachnida) Mite Mesostigmata BOLD:AAF9236 Mites (Arachnida) Whirligig mite Anystidae BOLD:ACR4249 Mites (Arachnida) Prostigmatic mite Trombidiformes BOLD:ACL6239 Springtails (Collembola) Slender springtail Entomobrya BOLD:ACI5504 Springtails (Collembola) Slender springtail Entomobryomorpha BOLD:AAI1229 Springtails (Collembola) Slender springtail Entomobryomorpha BOLD:AAI2228 Beetles (Coleoptera) Weevil Curculionidae BOLD:AAB3221 Beetles (Coleoptera) Striped ambrosia beetle Trypodendron lineatum BOLD:ACM3484 Beetles (Coleoptera) Sap beetle Nitidulidae BOLD:AAG4788 Flies (Diptera) Leaf miner fly Agromyzidae BOLD:AAP6787 Flies (Diptera) Leaf miner fly Agromyzidae BOLD:ACU8660 Flies (Diptera) Leaf miner fly Agromyzidae BOLD:AAG2477 Flies (Diptera) Root-maggot fly Pegomya BOLD:AAP9039 Flies (Diptera) Gall midge Cecidomyiidae BOLD:ABA6427 Flies (Diptera) Gall midge Cecidomyiidae BOLD:ACD6956 Flies (Diptera) Gall midge Cecidomyiidae BOLD:ABA6517 Flies (Diptera) Gall midge Cecidomyiidae BOLD:AAI4193 -

The Role of Chironomidae in Separating Naturally Poor from Disturbed Communities

From taxonomy to multiple-trait bioassessment: the role of Chironomidae in separating naturally poor from disturbed communities Da taxonomia à abordagem baseada nos multiatributos dos taxa: função dos Chironomidae na separação de comunidades naturalmente pobres das antropogenicamente perturbadas Sónia Raquel Quinás Serra Tese de doutoramento em Biociências, ramo de especialização Ecologia de Bacias Hidrográficas, orientada pela Doutora Maria João Feio, pelo Doutor Manuel Augusto Simões Graça e pelo Doutor Sylvain Dolédec e apresentada ao Departamento de Ciências da Vida da Faculdade de Ciências e Tecnologia da Universidade de Coimbra. Agosto de 2016 This thesis was made under the Agreement for joint supervision of doctoral studies leading to the award of a dual doctoral degree. This agreement was celebrated between partner institutions from two countries (Portugal and France) and the Ph.D. student. The two Universities involved were: And This thesis was supported by: Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT), financing program: ‘Programa Operacional Potencial Humano/Fundo Social Europeu’ (POPH/FSE): through an individual scholarship for the PhD student with reference: SFRH/BD/80188/2011 And MARE-UC – Marine and Environmental Sciences Centre. University of Coimbra, Portugal: CNRS, UMR 5023 - LEHNA, Laboratoire d'Ecologie des Hydrosystèmes Naturels et Anthropisés, University Lyon1, France: Aos meus amados pais, sempre os melhores e mais dedicados amigos Table of contents: ABSTRACT ..................................................................................................................... -

Biodiversity and Phenology of the Epibenthic Macroinvertebrate Fauna in a First Order Mississippi Stream

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Master's Theses Summer 8-2017 Biodiversity and Phenology of the Epibenthic Macroinvertebrate Fauna in a First Order Mississippi Stream Jamaal Bankhead University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/masters_theses Recommended Citation Bankhead, Jamaal, "Biodiversity and Phenology of the Epibenthic Macroinvertebrate Fauna in a First Order Mississippi Stream" (2017). Master's Theses. 308. https://aquila.usm.edu/masters_theses/308 This Masters Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BIODIVERSITY AND PHENOLOGY OF THE EPIBENTHIC MACROINVERTEBRATES FAUNA IN A FIRST ORDER MISSISSIPPI STREAM by Jamaal Lashwan Bankhead A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate School, the College of Science and Technology, and the Department of Biological Sciences at The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science August 2017 BIODIVERSITY AND PHENOLOGY OF THE EPIBENTHIC MACROINVERTEBRATES FAUNA IN A FIRST ORDER MISSISSIPPI STREAM by Jamaal Lashwan Bankhead August 2017 Approved by: ________________________________________________ Dr. David C. Beckett, Committee Chair Professor, Biological Sciences ________________________________________________ Dr. Kevin Kuehn, Committee