A Comparative Study of and Performer's Guide to Selected Songs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Recent Publications in Music 2010

Fontes Artis Musicae, Vol. 57/4 (2010) RECENT PUBLICATIONS IN MUSIC R1 RECENT PUBLICATIONS IN MUSIC 2010 Compiled and edited by Geraldine E. Ostrove On behalf of the Pour le compte de Im Auftrag der International l'Association Internationale Internationalen Vereinigung Association of Music des Bibliothèques, Archives der Musikbibliotheken, Libraries Archives and et Centres de Musikarchive und Documentation Centres Documentation Musicaux Musikdokumentationszentren This list contains citations to literature about music in print and other media, emphasizing reference materials and works of research interest that appeared in 2009. It includes titles of new journals, but no journal articles or excerpts from compilations. Reporters who contribute regularly provide citations mainly or only from the year preceding the year this list is published in Fontes Artis Musicae. However, reporters may also submit retrospective lists cumulating publications from up to the previous five years. In the hope that geographic coverage of this list can be expanded, the compiler welcomes inquiries from bibliographers in countries not presently represented. CONTRIBUTORS Austria: Thomas Leibnitz New Zealand: Marilyn Portman Belgium: Johan Eeckeloo Nigeria: Santie De Jongh China, Hong Kong, Taiwan: Katie Lai Russia: Lyudmila Dedyukina Estonia: Katre Rissalu Senegal: Santie De Jongh Finland: Tuomas Tyyri South Africa: Santie De Jongh Germany: Susanne Hein Spain: José Ignacio Cano, Maria José Greece: Alexandros Charkiolakis González Ribot Hungary: Szepesi Zsuzsanna Tanzania: Santie De Jongh Iceland: Bryndis Vilbergsdóttir Turkey: Paul Alister Whitehead, Senem Ireland: Roy Stanley Acar Italy: Federica Biancheri United Kingdom: Rupert Ridgewell Japan: Sekine Toshiko United States: Karen Little, Liza Vick. The Netherlands: Joost van Gemert With thanks for assistance with translations and transcriptions to Kersti Blumenthal, Irina Kirchik, Everett Larsen and Thompson A. -

LEON BOTSTEIN, Conductor

Thursday Evening, November 14, 2019, at 7:00 Isaac Stern Auditorium / Ronald O. Perelman Stage presents LEON BOTSTEIN, Conductor Performance #141: Season 5, Concert 12 ARTHUR HONEGGER Rugby (1928) (1891–1955) OTHMAR SCHOECK Lebendig begraben (Buried Alive), Op. 40 (1886–1957) (1926) MICHAEL NAGY, Baritone Intermission DIMITRI MITROPOULOS Concerto Grosso (1929) (1896–1960) Largo Allegro—Largo Chorale: Largo Allegro IGOR STRAVINSKY Divertimento, Symphonic Suite from the (1882–1971) Ballet The Fairy’s Kiss (1928, 1931, rev. ’32, ’34, ’49) Danses suisses (“Swiss Dances”) Scherzo Pas de deux a. Adagio b. Variation c. Coda This evening’s concert will run approximately 2 hours and 25 minutes including one 20-minute intermission. PLEASE SWITCH OFF YOUR CELL PHONES AND OTHER ELECTRONIC DEVICES. Notes ON THE MUSIC – TON’S KADEN HENDERSON ON ARTHUR HONEGGER’S RUGBY MATT DINE MATT Full Contact Music Honegger’s second tone poem, entitled Rugby, which we will be hearing today, was composed in 1928. Although it bears the name Rugby, the composer himself insisted that this work was not programmatic in a traditional sense. Despite what Honegger may have said, it takes little imagination to find oneself in the middle of the pitch dodging tack- les left and right from the very first note. Immediately from the downbeat it is apparent that Honegger is not alluding to two-hand-touch rugby, but rather the sport in its full contact, “hold no pris- oners” variety. The very first notes from The Composer the strings hit the audience like a ton of When thinking about the great orches- bricks as the cascading strings sweep us tral tone poems in our repertoire, the into a musical dogpile. -

Academiccatalog 2017.Pdf

New England Conservatory Founded 1867 290 Huntington Avenue Boston, Massachusetts 02115 necmusic.edu (617) 585-1100 Office of Admissions (617) 585-1101 Office of the President (617) 585-1200 Office of the Provost (617) 585-1305 Office of Student Services (617) 585-1310 Office of Financial Aid (617) 585-1110 Business Office (617) 585-1220 Fax (617) 262-0500 New England Conservatory is accredited by the New England Association of Schools and Colleges. New England Conservatory does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, age, national or ethnic origin, sexual orientation, physical or mental disability, genetic make-up, or veteran status in the administration of its educational policies, admission policies, employment policies, scholarship and loan programs or other Conservatory-sponsored activities. For more information, see the Policy Sections found in the NEC Student Handbook and Employee Handbook. Edited by Suzanne Hegland, June 2016. #e information herein is subject to change and amendment without notice. Table of Contents 2-3 College Administrative Personnel 4-9 College Faculty 10-11 Academic Calendar 13-57 Academic Regulations and Information 59-61 Health Services and Residence Hall Information 63-69 Financial Information 71-85 Undergraduate Programs of Study Bachelor of Music Undergraduate Diploma Undergraduate Minors (Bachelor of Music) 87 Music-in-Education Concentration 89-105 Graduate Programs of Study Master of Music Vocal Pedagogy Concentration Graduate Diploma Professional String Quartet Training Program Professional -

The Inventory of the Phyllis Curtin Collection #1247

The Inventory of the Phyllis Curtin Collection #1247 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center Phyllis Curtin - Box 1 Folder# Title: Photographs Folder# F3 Clothes by Worth of Paris (1900) Brooklyn Academy F3 F4 P.C. recording F4 F7 P. C. concert version Rosenkavalier Philadelphia F7 FS P.C. with Russell Stanger· FS F9 P.C. with Robert Shaw F9 FIO P.C. with Ned Rorem Fl0 F11 P.C. with Gerald Moore Fl I F12 P.C. with Andre Kostelanetz (Promenade Concerts) F12 F13 P.C. with Carlylse Floyd F13 F14 P.C. with Family (photo of Cooke photographing Phyllis) FI4 FIS P.C. with Ryan Edwards (Pianist) FIS F16 P.C. with Aaron Copland (televised from P.C. 's home - Dickinson Songs) F16 F17 P.C. with Leonard Bernstein Fl 7 F18 Concert rehearsals Fl8 FIS - Gunther Schuller Fl 8 FIS -Leontyne Price in Vienna FIS F18 -others F18 F19 P.C. with hairdresser Nina Lawson (good backstage photo) FI9 F20 P.C. with Darius Milhaud F20 F21 P.C. with Composers & Conductors F21 F21 -Eugene Ormandy F21 F21 -Benjamin Britten - Premiere War Requiem F2I F22 P.C. at White House (Fords) F22 F23 P.C. teaching (Yale) F23 F25 P.C. in Tel Aviv and U.N. F25 F26 P. C. teaching (Tanglewood) F26 F27 P. C. in Sydney, Australia - Construction of Opera House F27 F2S P.C. in Ipswich in Rehearsal (Castle Hill?) F2S F28 -P.C. in Hamburg (large photo) F2S F30 P.C. in Hamburg (Strauss I00th anniversary) F30 F31 P. C. in Munich - German TV F31 F32 P.C. -

REHEARSAL and CONCERT

Boston Symphony Orchestra* SYMPHONY HALL, BOSTON, HUNTINGTON AND MASSACHUSETTS AVENUES. (Telephone, 1492 Back Bay.) TWENTY-FOURTH SEASON, I 904-1905. WILHELM GERICKE, CONDUCTOR {programme OF THE FIFTH REHEARSAL and CONCERT VITH HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE NOTES BY PHILIP HALE. FRIDAY AFTERNOON, NOVEMBER J8, AT 2.30 O'CLOCK. SATURDAY EVENING, NOVEMBER J9, AT 8.00 O'CLOCK. Published by C'A. ELLIS, Manager. 265 CONCERNING THE "QUARTER (%) GRAND" Its Tone Quality is superior to that of an Upright. It occupies practically no more space than an Upright. It costs no more than the large Upright. It weighs less than the larger Uprights. It is a more artistic piece of furniture than an Upright. It has all the desirable qualities of the larger Grand Pianos. It can be moved through stairways and spaces smaller than will admit even the small Uprights. RETAIL WARE ROOMS 791 TREMONT STREET BOSTON Established 1823 : TWENTY-FOURTH SEASON, J904-J905. Fifth Rehearsal and Concert* FRIDAY AFTERNOON, NOVEMBER J8, at 2.30 o'clock- SATURDAY EVENING, NOVEMBER t% at 8.00 o'clock. PROGRAMME. Brahms ..... Symphony No. 3, in F major, Op. go I. Allegro con brio. II. Andante. III. Poco allegretto. IV. Allegro. " " " Mozart . Recitative, How Susanna delays ! and Aria, Flown " forever," from " The Marriage of Figaro Wolf . Symphonic Poem, " Penthesilea," after the like-named' tragedy of Heinrich von Kleist (First time.) " Wagner ..... Finale of " The Dusk of the Gods SOLOIST Mme. JOHANNA GADSKI. There will be an intermission of ten minutes after the Mozart selection. SPECIAL ANNOUNCEMENT. By general desire the concert announced for Saturday evening, Decem- ber 24, '* Christmas Eve," will be given on Thursday evening, December 2a. -

General Index

Cambridge University Press 0521780098 - The Cambridge Companion to Twentieth-Century Opera Edited by Mervyn Cooke Index More information General index Abbate, Carolyn 282 Bach, Johann Sebastian 105 Adam, Fra Salimbene de 36 Bachelet, Alfred 137 Adami, Giuseppe 36 Baden-Baden 133 Adamo, Mark 204 Bahr, Herrmann 150 Adams, John 55, 204, 246, 260–4, 289–90, Baird, Tadeusz 176 318, 330 Bala´zs, Be´la 67–8, 271 Ade`s, Thomas 228 ballad opera 107 Adlington, Robert 218, 219 Baragwanath, Nicholas 102 Adorno, Theodor 20, 80, 86, 90, 95, 105, 114, Barbaja, Domenico 308 122, 163, 231, 248, 269, 281 Barber, Samuel 57, 206, 331 Aeschylus 22, 52, 163 Barlach, Ernst 159 Albeniz, Isaac 127 Barry, Gerald 285 Aldeburgh Festival 213, 218 Barto´k, Be´la 67–72, 74, 168 Alfano, Franco 34, 139 The Wooden Prince 68 alienation technique: see Verfremdungse¤ekt Baudelaire, Charles 62, 64 Anderson, Laurie 207 Baylis, Lilian 326 Anderson, Marian 310 Bayreuth 14, 18, 21, 49, 61–2, 63, 125, 140, 212, Andriessen, Louis 233, 234–5 312, 316, 335, 337, 338 Matthew Passion 234 Bazin, Andre´ 271 Orpheus 234 Beaumarchais, Pierre-Augustin Angerer, Paul 285 Caron de 134 Annesley, Charles 322 Nozze di Figaro, Le 134 Ansermet, Ernest 80 Beck, Julian 244 Antheil, George 202–3 Beckett, Samuel 144 ‘anti-opera’ 182–6, 195, 241, 255, 257 Krapp’s Last Tape 144 Antoine, Andre´ 81 Play 245 Apollinaire, Guillaume 113, 141 Beeson, Jack 204, 206 Appia, Adolphe 22, 62, 336 Beethoven, Ludwig van 87, 96 Aquila, Serafino dall’ 41 Eroica Symphony 178 Aragon, Louis 250 Beineix, Jean-Jacques 282 Argento, Dominick 204, 207 Bekker, Paul 109 Aristotle 226 Bel Geddes, Norman 202 Arnold, Malcolm 285 Belcari, Feo 42 Artaud, Antonin 246, 251, 255 Bellini, Vincenzo 27–8, 107 Ashby, Arved 96 Benco, Silvio 33–4 Astaire, Adele 296, 299 Benda, Georg 90 Astaire, Fred 296 Benelli, Sem 35, 36 Astruc, Gabriel 125 Benjamin, Arthur 285 Auden, W. -

Alban Berg's Filmic Music

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2002 Alban Berg's filmic music: intentions and extensions of the Film Music Interlude in the Opera Lula Melissa Ursula Dawn Goldsmith Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Goldsmith, Melissa Ursula Dawn, "Alban Berg's filmic music: intentions and extensions of the Film Music Interlude in the Opera Lula" (2002). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 2351. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/2351 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. ALBAN BERG’S FILMIC MUSIC: INTENTIONS AND EXTENSIONS OF THE FILM MUSIC INTERLUDE IN THE OPERA LULU A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The College of Music and Dramatic Arts by Melissa Ursula Dawn Goldsmith A.B., Smith College, 1993 A.M., Smith College, 1995 M.L.I.S., Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, 1999 May 2002 ©Copyright 2002 Melissa Ursula Dawn Goldsmith All rights reserved ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS It is my pleasure to express gratitude to my wonderful committee for working so well together and for their suggestions and encouragement. I am especially grateful to Jan Herlinger, my dissertation advisor, for his insightful guidance, care and precision in editing my written prose and translations, and open mindedness. -

Understanding Music Past and Present

Understanding Music Past and Present N. Alan Clark, PhD Thomas Heflin, DMA Jeffrey Kluball, EdD Elizabeth Kramer, PhD Understanding Music Past and Present N. Alan Clark, PhD Thomas Heflin, DMA Jeffrey Kluball, EdD Elizabeth Kramer, PhD Dahlonega, GA Understanding Music: Past and Present is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribu- tion-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. This license allows you to remix, tweak, and build upon this work, even commercially, as long as you credit this original source for the creation and license the new creation under identical terms. If you reuse this content elsewhere, in order to comply with the attribution requirements of the license please attribute the original source to the University System of Georgia. NOTE: The above copyright license which University System of Georgia uses for their original content does not extend to or include content which was accessed and incorpo- rated, and which is licensed under various other CC Licenses, such as ND licenses. Nor does it extend to or include any Special Permissions which were granted to us by the rightsholders for our use of their content. Image Disclaimer: All images and figures in this book are believed to be (after a rea- sonable investigation) either public domain or carry a compatible Creative Commons license. If you are the copyright owner of images in this book and you have not authorized the use of your work under these terms, please contact the University of North Georgia Press at [email protected] to have the content removed. ISBN: 978-1-940771-33-5 Produced by: University System of Georgia Published by: University of North Georgia Press Dahlonega, Georgia Cover Design and Layout Design: Corey Parson For more information, please visit http://ung.edu/university-press Or email [email protected] TABLE OF C ONTENTS MUSIC FUNDAMENTALS 1 N. -

What Is Atonality (1930)

What is Atonality? Alban Berg April 23, 1930 A radio talk given by Alban Berg on the Vienna Rundfunk, 23 April 1930, and, printed under the title “Was ist atonal?” in 23, the music magazine edited by Willi Reich, No. 26/27, Vienna, 8 June 1936. Interlocutor: Well, my dear Herr Berg, let’s begin! considered music. Alban Berg: You begin, then. I’d rather have the last Int.: Aha, a reproach! And a fair one, I confess. But word. now tell me yourself, Herr Berg, does not such a Int.: Are you so sure of your ground? distinction indeed exist, and does not the negation of relationship to a given tonic lead in fact to the Berg: As sure as anyone can be who for a quarter- collapse of the whole edifice of music? century has taken part in the development of a new art — sure, that is, not only through understanding Berg: Before I answer that, I would like to say this: and experience, but — what is more — through Even if this so-called atonal music cannot, har- faith. monically speaking, be brought into relation with a major/minor harmonic system — still, surely, Int.: Fine! It will be simplest, then, to start at once with there was music even before that system in its turn the title of our dialogue: What is atonality? came into existence. Berg: It is not so easy to answer that question with a for- Int.: . and what a beautiful and imaginative music! mula that would also serve as a definition. When this expression was used for the first time — prob- Berg: . -

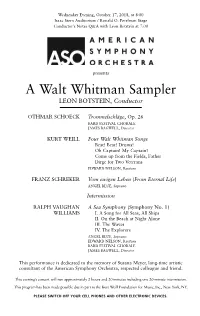

A Walt Whitman Sampler LEON BOTSTEIN, Conductor

Wednesday Evening, October 17, 2018, at 8:00 Isaac Stern Auditorium / Ronald O. Perelman Stage Conductor’s Notes Q&A with Leon Botstein at 7:00 presents A Walt Whitman Sampler LEON BOTSTEIN, Conductor OTHMAR SCHOECK Trommelschläge, Op. 26 BARD FESTIVAL CHORALE JAMES BAGWELL, Director KURT WEILL Four Walt Whitman Songs Beat! Beat! Drums! Oh Captain! My Captain! Come up from the Fields, Father Dirge for Two Veterans EDWARD NELSON, Baritone FRANZ SCHREKER Vom ewigen Leben (From Eternal Life) ANGEL BLUE, Soprano Intermission RALPH VAUGHAN A Sea Symphony (Symphony No. 1) WILLIAMS I. A Song for All Seas, All Ships II. On the Beach at Night Alone III. The Waves IV. The Explorers ANGEL BLUE, Soprano EDWARD NELSON, Baritone BARD FESTIVAL CHORALE JAMES BAGWELL, Director This performance is dedicated to the memory of Susana Meyer, long-time artistic consultant of the American Symphony Orchestra, respected colleague and friend. This evening’s concert will run approximately 2 hours and 20 minutes including one 20-minute intermission. This program has been made possible due in part to the Kurt Weill Foundation for Music, Inc., New York, NY. PLEASE SWITCH OFF YOUR CELL PHONES AND OTHER ELECTRONIC DEVICES. FROM THE Music Director Whitman and Democracy comprehend the English of Shakespeare by Leon Botstein or even Jane Austen without some reflection. (Indeed, even the space Among the most arguably difficult of between one generation and the next literary enterprises is the art of transla- can be daunting.) But this is because tion. Vladimir Nabokov was obsessed language is a living thing. There is a about the matter; his complicated and decided family resemblance over time controversial views on the processes of within a language, but the differences transferring the sensibilities evoked by in usage and meaning and in rhetoric one language to another have them- and significance are always developing. -

Modern Art Music Terms

Modern Art Music Terms Aria: A lyrical type of singing with a steady beat, accompanied by orchestra; a songful monologue or duet in an opera or other dramatic vocal work. Atonality: In modern music, the absence (intentional avoidance) of a tonal center. Avant Garde: (French for "at the forefront") Modern music that is on the cutting edge of innovation.. Counterpoint: Combining two or more independent melodies to make an intricate polyphonic texture. Form: The musical design or shape of a movement or complete work. Expressionism: A style in modern painting and music that projects the inner fear or turmoil of the artist, using abrasive colors/sounds and distortions (begun in music by Schoenberg, Webern and Berg). Impressionism: A term borrowed from 19th-century French art (Claude Monet) to loosely describe early 20th- century French music that focuses on blurred atmosphere and suggestion. Debussy "Nuages" from Trois Nocturnes (1899) Indeterminacy: (also called "Chance Music") A generic term applied to any situation where the performer is given freedom from a composer's notational prescription (when some aspect of the piece is left to chance or the choices of the performer). Metric Modulation: A technique used by Elliott Carter and others to precisely change tempo by using a note value in the original tempo as a metrical time-pivot into the new tempo. Carter String Quartet No. 5 (1995) Minimalism: An avant garde compositional approach that reiterates and slowly transforms small musical motives to create expansive and mesmerizing works. Glass Glassworks (1982); other minimalist composers are Steve Reich and John Adams. Neo-Classicism: Modern music that uses Classic gestures or forms (such as Theme and Variation Form, Rondo Form, Sonata Form, etc.) but still has modern harmonies and instrumentation. -

Goldmark's Wild Amazons Drama and Exoticism in the Penthesilea Overture

Goldmark’s Wild Amazons Drama and Exoticism in the Penthesilea Overture Jane ROPER Royal College of Music, Prince Consort Road, London E-mail: [email protected] (Received: June 2016; accepted: March 2017) Abstract: Goldmark was the first of several composers to write a work based on Heinrich von Kleist’s controversial play, Penthesilea. Early critical opinion about the overture was divided. Hanslick found it distasteful, whereas others were thrilled by Goldmark’s powerful treatment of the subject. Composed in 1879, during the 1880s Penthesilea became established in orchestral repertoire throughout Europe and Amer- ica. The overture represents the conflict of violence and sexual attraction between the Queen of the Amazons and Achilles. Exoticism in the play is achieved by contrasting brutal violence, irrational behaviour and extreme sensual passion. This is recreated musically by drawing on topics established in opera. Of particular note is the use of dissonance and unexpected modulations, together with extreme rhythmic and dy- namic contrast. A key feature of the music is the interplay between military rhythms representing violence and conflict, and a legato, rocking theme which suggests desire and sensuality. Keywords: Goldmark, Exoticism, Penthesilea Overture The Penthesilea Overture, op. 31, is arguably Carl Goldmark’s most controversial work. Its content is provocative. Consider first of all the subject matter: Goldmark transports us to the battlefield of Troy in the twelfth century BC. Penthesilea, Queen of the Amazons, a terrifying, ferocious warrior tribe of women, gallops onto the scene with her retinue. The Amazons are bloodthirsty and hungry for sex, anticipating the men they will capture to enact their fertility ritual.