Cooking on Campaign

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HANDS Can He LOVELIER!

all inter* la thla eol- 11»* ahorter the letter* the betti i * printed F>OHimi The Americas Weeklj will None aknnld he mare thaa M* ward pay A prl*e winning recipe la Addrea* them la The America > ft. Hon*e Almanac! Echoes awarded U. the aame a* an the Weekly wife'# Food . manack Almanack page. lie aure ta nrlt* I*. O. Hox 111. Urand C entral Annex, r-r-1 AJ yaar aame and nddren* plainly. New Yark City. School Day Memories of Mother's Cooking and cook another half hour. Keep reading our Sunday paper. He FABRICS 1 By Mrs. Pet«r Msrkuskl, plenty of liquid on meat for had part of It and I ths rest. I PmHa, 111. gravy. Should thicken Itself If said to him "We surely get our dear to our hetrU af® meat waa well floured. money's worth out of our Sun- ARE GETTING the acenea and memories Beas Jack, day paper " He looked at me HOWof our childhood! Piedmont, California. and said, "Yes we do. kid. and SCARCE! We trudged home two miles (Mra. Jack, your Jim Smith recipe especially so on your Almanack You could smell auggeat an egcellenl way of prepar- pags." Your Prnciout Oroitos from school. ing round steak.—Mary Lee Swann.) Protect* mother's Uma bean chowder after Mrs. John Thomas. and Undint Againtt Undnrarm you passed the third door down MONEY’S WORTH Morgantown, West Virginia. "Pnnpiration Rot" With Nonapil and the smell of It put new life fMr* Thoms*, we re very glad you Dear Almanack: p«ge* helpful We hope into our weary legs. -

Shanghai Fried Rice with Salt Pork and Green Pak Choy Xian Rou Cai Fan 咸肉菜饭

Shanghai fried rice with salt pork and green pak choy xian rou cai fan 咸肉菜饭 In a backstreet not far from Nanjing Road in the heart of Shanghai, there’s 4 dried shiitake mushrooms 2 tbsp cooking oil, preferably a small diner that serves one of the most ½ small red onion lard delicious versions of this classic local rice 100g streaky salt pork, 1 tbsp finely chopped dish I’ve tasted. The plump, glossy rice, pancetta or unsmoked fresh ginger studded with salt pork, threaded with the bacon 1 tsp sesame oil bright green of pak choy, is irresistible. 275g green pak choy Salt and ground white Everyone eats it, in the Chinese manner, (3–4 heads) pepper with a bowl of broth to refresh the palate 600g cooked and cooled (a simple stock with sliced spring onion sushi rice (300g when raw) greens will do). This is my version of their recipe, which includes red onion Cover the shiitake mushrooms in boiling water and leave to and shiitake mushrooms. This dish is soak for half an hour. Finely chop the onion. Remove any rind usually made with short-grain white rice from the pork and chop it into dice. Remove the mushroom – Japanese sushi rice is what I use at stalks and dice the caps. Chop the green pak choy a little more home – but it will also taste delicious coarsely than the other ingredients. Break the rice up into small with long-grain Thai fragrant rice. For clumps to make stir-frying easier. the most sizzlingly delicious results, use lard as your cooking oil. -

SC076 1919 Home Preparation of Pork

HOME PREPARATION OF PORK A. M. PATERSON The cost of meat cured on the farm is much less than that purchased from the retailer. An average 200-pound hog should dress 160 pounds. For the past 10 years this 160 pounds of meat could have been produced, slaughtered, and cured on the farm for 35 percent less than it would have cost the farmer at his local market. BUTCHERING Only hogs that are healthy, fat, and gaining in weight should be selected for slaughter. Meat from such animals is more palatable and will keep longer whether fresh or cured. Ani- mals in poor health when slaughtered may be affected with some disease that is injurious when the meat is used as food. Meat from unhealthy animals is also likely to spoil quickly, and may be difficult to keep after curing. The meat from a fat animal is much more palatable than that from a thin animal. If an animal is losing in flesh at the time of slaughter the carcass will contain a larger percent of water and a less palatable meat will be the result. Hogs should be kept off feed for about 15 hours before slaughtering. Such animals will bleed better and the meat will be of better quality. It is also essential that hogs be kept as quiet as possible before butchering and not chased or beaten. Rough treatment will bruise the animal or cause a rise in tem- perature. Bleeding.-Do not shoot or stun a hog before sticking as stunning in any way is liable to retard the bleeding. -

Easy Recipes – June 2012

Across the Fence Quick and Easy Recipes – June 2012 “Open a Box or Can--1, 2, 3 Recipes” Carolyn Peake's Recipes Raspberry-Cheese Balls 2 pkgs. (8 oz. each) cream cheese, 4 Tbsp. raspberry preserves softened 1 cup finely chopped pecans Beat cream cheese until creamy. Beat in the raspberry preserves and blend well. Shape into a ball and roll in chopped pecans. Serve with crackers. Quick Pumpkin Bread 1 pkg. (16 oz.) pound cake mix ⅓ cup milk 1 cup canned pumpkin 1 tsp. allspice 2 eggs With mixer, combine all ingredients and blend well. Pour into a greased and floured 9x5-inch loaf pan. Bake at 350°F for 1 hour, checking with a toothpick for when it is done. Cool and turn out onto a rack to finish cooling. Broccoli Salad 5 cups cut broccoli florets 1 cup chopped celery 1 sweet red bell pepper, julienned 8 to 12 oz. Monterey Jack cheese, cubed Combine all ingredients and mix well. Toss with Italian or your favorite dressing. Chill. Miracle Cake 1 pkg. (18 oz.) lemon cake mix 1 can (20 oz.) crushed pineapple 3 eggs with juice ⅓ cup oil In a mixing bowl, combine all ingredients, blending on low speed then beat on medium for 2 minutes. Pour batter into greased and floured 9x13 x2-inch pan. Bake at 350°F for 30 to 35 minutes until cake tests done with toothpick. Miracle Cake Topping: 1 can (14 oz.) sweetened condensed milk ¼ cup lemon juice 1 container (8 oz.) whipped topping Blend all ingredients and mix well. -

Pre-Seventeenth Century Bacon: from Piers Plowman to Sir Kenelm Digby

Pre-seventeenth Century Bacon: from Piers Plowman to Sir Kenelm Digby The Honorable Tomas de Courcy (JdL, GdS) Avacal Arts & Sciences Championship April 7, 2018 1 Contents Abstract ......................................................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 2 Consumption of Pork in England................................................................................................................... 4 Documenting Bacon ...................................................................................................................................... 5 Bacon Production and Storage ................................................................................................................... 16 Food safety .................................................................................................................................................. 21 Conclusions ................................................................................................................................................. 23 Works Cited ................................................................................................................................................. 25 Abstract This research attempts to fill a gap in historical food scholarship by examining the methods used prior to the seventeenth -

GIRLS' COOKING CLUB (FIRST YEAR) by CHARLOTTE E

-L'-- ~ r I;LH',' '"" ' '.~ r.... ~ 'J'" ,....... ·LL(~ li li m """" !!!iii! iiii! if !!.Ii ii!i!!!iii"" iiii!iii' iili"ii,,!' liii,,' ""m"!!!!!! """iii""" ""iii Hili""",,! "",,'m !!,,! "iii,!!i,," """!iii',,,,',,! liiliiil.!iiiiilii!!iii "",,1m !lim January, 1917 Extension Bulletin Series I, No. I 16 Colorado Agricultural College EXTENSION SERVICE Fort Collin.. Colorado H. T. FRENCH. Director ~~I:'======Jlilt:===Jiil======:::J'== GIRLS' COOKING CLUB (FIRST YEAR) By CHARLOTTE E. CARPENTER Assistant Professor in Home Economics MAUDE E. SHERIDAN As.istant State Club Leader of Boy; and Girls' Clubs Colorado Agricultural College I I EJ EJ EJ EJ I I ~=r::::'=====Jlit===:J'C'=====,== CO·OPERATIVE EXTENSION SERVICE IN AGRICULTURE AND HOME ECONOMICS-COLORADO AGRICULTURAL COLLEGE AND U. S. DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE CO·OPERATING Q DWii!!ii!!!! !i!!!iii!l!i!!ii!iiiii!!!!i!iiii!ii!!!!' ',ijj,i'!!'!!!!!!!!,!!!!!!' III ill!!!!!iiii!!iliiii!!!!iiiii!!lllliii!!i!!!!!iiiiliiiID E1 •. iii':!ii!!!!!!.!!!!!!!!!. i!!!i!!!!iii!!!!i!i!i!!!!i!!i!!iii!!!!!!iiiiiii!!i!!!m. EI Colorado Agricultural College FoRT COUJNS, COLORADO CHAS. A. LORY, President EXTENSION SERVICE He .T. FRBNCH•••..•.•••.•.•••.....••••.••••••DIBBCTOB A. E. LOVBTT. STATB LBADBB COUNTY AGBICUIJrUB.lL AGBHTS IDA .L. SMITH•••••••••••••..••.•••••.•BDCUTIVB CLBBJt EXTENSION STAFF :". BL VAPLON•••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• STATBLBADBB CLUB lVOBK ·W. JI. FOARD•••••••••••••••• ••••• ••• • •••••••FABK MANAGBKENT DBKONS'1'1U.TION~ '1IIRIAII II. BAyNES•••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••HOJIJIEcONOMIC.8 -

Meat Is Needed

MEAT IS NEEDED To Build Muscle To Build Blood To Add Flavor Market Order Menus Meat Recipes Published by the National Live Stock and Meat Board 407 South Dearborn St. CHICAGO, ILLINOIS Furnished free upon request—Single copies or in quantities* A Week's Food Supply The grocery order given below is planned for a family of five, two adults and three children. It includes all foods needed to keep the family well. Other items of like food value may be bought in place of those in the list. There are many other cuts of meat which may be used to give variety to the meals. All the cuts of meat which may be fitted into the low cost meal are given on page 3 of this leaflet. The prices quoted in this market order prevailed in Chicago during January, 1933. They will vary in different markets and in different localities. MEATS Pork Should«« Roast—3 pounds $ .27 Ground Beef—1% pounds 15 Breast of Lamb—2 pound« 10 Lamb Stew—2 pounds or Salmon—1 can 10 B«ef Pot-roast—2 V2 pounds 30 Pork Liver—2 pounds 14 Pork Heart—2 pounds 16 VEGETABLES Potatoes—20 pound* 20 Carrots—3 pounds 15 Onions—2 pounds 07 Tomatoes—5 No. 2 cans 40 Cabbage—2 pounds 10 Spinach—2 pounds 15 Turnips—2 pounds 07 Beans, navy—1 pound 05 CEREALS AND BREADS Bread (half white and half whole wheat)—10 loaves. .50 Flour—2 pounds 11 Rolled Oats—1 pound 05 Cornmeal—1 pound 03 Macaroni—1 package 07 Rice—1 pound 05 FRUITS Oranges—1 dozen 20 Apples—4 pounds 19 Prunes—1 pound 06 Dates—1 pound 10 Raisin»—pound .04 MILK Milk—12 quarts 1.08 Milk, evaporated—12 "tall" cans .66 EGGS Eggs—Vz dozen JfcT FATS Lard—2 pounds 11 Butter—y2 pound 14 Butter substitute—Vz pound 08 Bacon square—1 pound 11 Salt Pork—% pound 05 SWEETS Sugar, granulated—2 pounds 13 Sugar, brown—2 pounds 15 MISCELLANEOUS Coffee—Yz pound 09 Tea—% pound 05 Cocoa—pound 07 Miscellaneous 15 Cod-liver Oil for Children 14 Total $6.98 A Week9s Menus The menus given below are planned around the grocery order on page 1. -

Pork on the Farm: Dressing - Curing - Canning F

South Dakota State University Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange Cooperative Extension Circulars: 1917-1950 SDSU Extension 1-1932 Pork on the Farm: Dressing - Curing - Canning F. U. Fenn I. B. Johnson Mary A. Dolve Follow this and additional works at: http://openprairie.sdstate.edu/extension_circ Recommended Citation Fenn, F. U.; Johnson, I. B.; and Dolve, Mary A., "Pork on the Farm: Dressing - Curing - Canning" (1932). Cooperative Extension Circulars: 1917-1950. Paper 314. http://openprairie.sdstate.edu/extension_circ/314 This Circular is brought to you for free and open access by the SDSU Extension at Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cooperative Extension Circulars: 1917-1950 by an authorized administrator of Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Table of Contents Page Selecting the Hogs for Butchering _____________ 3 Care of Hogs Before Butchering ----------�---- 4 Equipment for Farm Butchering ______________ 4 Killing the Hog------------------------------ 5 Scalding and Scraping ________________ ________ 7 Removing the Entrails _______________________ 8 Cooling the Carcass ---- -------- ------ --- ----- 10 Cutting the Carcass-------- --- -- ------- ------ 13 Head -- -- ----- ------ -- --- ---- ---------- - 14 Shoulder ------------ --- ------ ---------- 14 Ham ------ -

Roll Your Own Baconfest Guide

BACONFESTCHICAGO: 2012 Menu and Roll-Your-Own Baconfest Guide Restaurant Dish Description Shift I don’t have a ticket! HOW CAN I EAT IT TOO? 2 Sparrows Bacon Krispie Treats with maple & bacon dinner Available as a special for one month following doughnut holes Baconfest. Chef Greg Ellis adds, “We have plenty of other bacon dishes on our menu (seeing that we are a breakfast and lunch restaurant).” 676 Restaurant & Bar Widmer six-year cheddar cheese with dinner Both are available as a regular menu item. Nueske’s bacon jam Plus don’t miss: Gunthorp Farm Pig & Chips, also on House-made Catalpa Grove lamb bacon with the regular menu. 676 honey hive mustard 694 Wine & Spirits The Kick-Ass BLT dinner Available as a special every Tuesday. Atwood Cafe Willy Wonka meets Bacon - an array of Wonka dinner -inspired candies done with bacon Autre Monde Cafe Bacon Confit with Tropea Onion Agrodolce - lunch Available as a special 4/13 - 4/15. confit of apple-wood smoked and peppered Nueske’s bacon with tropea onion agrodolce. BaCaro Bacon and Egg Sandwich – Triple-S Farm lunch bacon, fried egg puree, pickled ramp relish, misato radish, and bacon challah Bakin' & Eggs Bacon chocolate chip cookies dinner Cheddar and bacon scones Jalapeno bacon and smoked gouda mac -n- cheese Barn & Company Smoked brisket slider with bacon jam and lunch bacon BBQ sauce The Bedford Bacon beignets, bacon sugar, dinner bacon/walnut/bourbon infused maple caramel Benny's Chop House Nueske’s bacon and pork head cutlet with lunch Michigan spring ramp kimchi on buttermilk biscuits, -

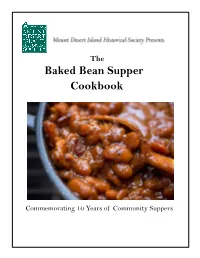

Cookbook Baked Bean Supper

The Baked Bean Supper Cookbook Commemorating 10 Years of Community Suppers Baked Bean Supper Cookbook Editorial Team Mount Desert Island Historical Society Program Committee Kathy MacLeod, Committee Chair William Horner, M.D., Board President Pauline Angione Peter Collier Elise Frank Nicole Ouellette Leah Lucey, Director of Operations Raney Bench, Executive Director Special thanks to the community members who contributed their recipes and donated their dishes over the past 10 years. ©2021 by Mount Desert Island Historical Society. All rights reserved. Please address all inquiries to: Mount Desert Island Historical Society PO Box 653 Mount Desert, ME 04660 [email protected] www.mdihistory.org 2 IN MEMORIAM RAYMOND STROUT <> An Extraordinary Man On Friday, November 6, 2020 our island communities lost a giant of our collective history. Raymond Strout, Class of 1959, Bar Harbor High School died quietly in his home on Russell Farm Road in the Emery District of rural Bar Harbor, whence he had come. He had a passion for island history. It was, simply put, his life’s work. He was an oracle of sorts and was the go-to man for anything to do with Bar Harbor history, in particular. He had a mysterious collection that was sequestered away in an unpretentious building down behind the old Ahlblad’s Paint Shop. He presided over this mostly hidden trove from an old tilt -back wooden office chair, from which he would answer softly and knowingly your question and inevitably offer you a “teaser” about a rare document or photograph he had come by. “Oh, would you like to see the guest register from the 1856 season of the Agamont House?” Raymond was extremely generous to people of all stripes, from organizers of the latest Bar Harbor High School Reunion to the serious researcher. -

Aunt Sammy's Radio Recipes Revised

-- Inc-. ■ • • • • • • • • • • • • • • ■ ♦ UNITED STATES DEPARTMENTof AGRICULTURE ♦ BUREAU OF HOME ECONOMICS ♦ 1-----------------------1♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ AUNT SAMMY'S ♦ ♦ RADIO RECIPES ♦ ♦ REVISED ♦ ♦ • ♦ ♦ ♦ RUTH VAN DEMAN, Associate Specialist ♦ in Charge of Information ♦ ♦ and ♦ FANNY WALKER YEATMAN, Junior Specialist in Foods ♦ BUREAU OF HOME ECONOMICS ♦ ♦ • ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ Is�ued May, 1931 ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ UNITED ST ATES ♦ GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE ♦ WASHINGTON· 1931 ♦ ♦ • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, Washington. D, C, • • , • • Price 1$ cents Contents· • Page Foreword.... .. .. v Menus.................................... 1 Oven temperatures. .. .. .. 8 Equivalent measures. .. .. .. .. .. 8 Soups and chowders. .. .. .. 9 Meats..................................... 14 Poultry..................................... 24 · Fish and shellfish.. .. .. .. .. .. .. 30 Egg and cheese dishes. .. .. .. .. .. 37 Vegetables . .. .. .. .. .. 40 Salads and salad dressings . .. 64 Sandwiches. .. .. .. .. .. 71 Sauces............... ............ .......· .... 74 Biscuits, muffins, and breads. .. .. .. .. 78 Fruits and puddings . .. .. .. .. .. .. 84 Pies and other pastries.. .. .. .. .. 103 Ca'l{es, coo'l{ies, and frostings.. .. .. .. .. .. 110 Ice creams and frozen desserts ...........-. .. 122 Candies and confections.. .. .. .. .. 126 Jams, preserves, and relishes... .. .. .. .. .. 132 Index to recipes. .. 139 III Foreword A U.TN SAMMY 's RADIO RECIPES, REVISED, brings together 400 of the mostpopular -

The Bacon Cookbook: More Than 150 Recipes from Around the World for Everyones Favorite Food Pdf

FREE THE BACON COOKBOOK: MORE THAN 150 RECIPES FROM AROUND THE WORLD FOR EVERYONES FAVORITE FOOD PDF James Villas,Andrea Grablewski | 288 pages | 19 Oct 2007 | Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company | 9780470042823 | English | Hoboken, NJ, United States Goodreads helps you keep track of books you want to read. Want to The Bacon Cookbook: More Than 150 Recipes from Around the World for Everyones Favorite Food saving…. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. Other editions. Enlarge cover. Error rating book. Refresh and try again. Open Preview See a Problem? Details if other :. Thanks for telling us about the problem. Return to Book Page. Get A Copy. Hardcoverpages. Published September 14th by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. More Details Original Title. Other Editions 3. Friend Reviews. To see what your friends thought of this book, please sign up. To ask other readers questions about The Bacon Cookbookplease sign up. Lists with This Book. This book is not yet featured on Listopia. Community Reviews. Showing Average rating 3. Rating details. More filters. Sort order. Jun 24, Stephen rated it it was amazing. Bacon may just be the most wonderful meat product in the world. This could explain why it is so often the gateway through which vegetarians pass on their road back to being carnivores. James Villas, a true Son of the South, where raising hogs and making bacon is a sort of religion, writes encyclopedically about cured pork parts. His world travels in pursuit of other food stories often exposed him to regional bacons and the dishes made with them. He compiles of these recipes in an excellent c Bacon may just be the most wonderful meat product in the world.