Research Toward a Cure and Immune-Based Therapies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Altering Cell Death Pathways As an Approach to Cure HIV Infection

Citation: Cell Death and Disease (2013) 4, e718; doi:10.1038/cddis.2013.248 OPEN & 2013 Macmillan Publishers Limited All rights reserved 2041-4889/13 www.nature.com/cddis Review Altering cell death pathways as an approach to cure HIV infection AD Badley*,1,2, A Sainski2,3, F Wightman4,5 and SR Lewin4,5 Recent cases of successful control of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) by bone marrow transplant in combination with suppressive antiretroviral therapy (ART) and very early initiation of ART have provided proof of concept that HIV infection might now be cured. Current efforts focusing on gene therapy, boosting HIV-specific immunity, reducing inflammation and activation of latency have all been the subject of recent excellent reviews. We now propose an additional avenue of research towards a cure for HIV: targeting HIV apoptosis regulatory pathways. The central enigma of HIV disease is that HIV infection kills most of the CD4 T cells that it infects, but those cells that are spared subsequently become a latent reservoir for HIV against which current medications are ineffective. We propose that if strategies could be devised which would favor the death of all cells which HIV infects, or if all latently infected cells that release HIV would succumb to viral-induced cytotoxicity, then these approaches combined with effective ART to prevent spreading infection, would together result in a cure for HIV. This premise is supported by observations in other viral systems where the relationship between productive infection, apoptosis resistance, and the development of latency or persistence has been established. Therefore we propose that research focused at understanding the mechanisms by which HIV induces apoptosis of infected cells, and ways that some cells escape the pro-apoptotic effects of productive HIV infection are critical to devising novel and rational approaches to cure HIV infection. -

The Importance of Community Engagement in Hiv Cure Research

tagline Vol. 26, No. 1, May 2019 SCIENTIFIC COMPLEXITY AND ETHICAL UNCERTAINTIES: THE IMPORTANCE OF COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT IN HIV CURE RESEARCH By Richard Jefferys Introduction The past decade has seen a major expansion of the research Recent presentations at the March 2019 CROI indicate that effort to develop a cure for HIV infection. The U.S. National two additional people may have joined Brown,6,7 but follow-up Institutes of Health (NIH), the world’s largest biomedical is far shorter: One of the individuals has been off ART without research funder, has identified the pursuit of a cure as one of evidence of HIV rebound for 18 months, while the other is at five primary priorities for HIV.1 Total global financial support about four months. increased substantially in the period 2012–2017, from $88 million to $288.8 million.2 In 2014, TAG launched an online Translating to a Wider Community listing of cure-related clinical research drawn from registries (primarily ClinicalTrials.gov). The list initially contained less These additional cases of possible cures are encouraging, than 50 entries; it currently includes 98 clinical trials and 34 but the method used to achieve this outcome cannot be observational studies that are ongoing.3 Over 7,000 people used in most people with HIV, who do not require stem cell are expected to enroll in these studies. transplants for cancer (the high mortality risk associated with transplantation precludes its use outside of this setting). As with other areas of HIV research, engagement of the community of people living with HIV and their advocates is In the absence of any known safe alternatives for obtaining vital for ensuring that the conduct of cure-related studies is similarly robust depletion of HIV from the body, investigators ethical, appropriate, and responsive to community priorities. -

G HIV/AIDS & Immune Evasion Strategies the Year 1981…

Micro 320: Infectious Disease & Defense HIV/AIDS & Immune Evasion Strategiesg Wilmore Webley Dept. of Microbiology The Year 1981… Reported by MS Gottlieb, MD, HM Schanker, MD, PT Fan, MD, A Saxon, MD, JD Weisman, DO, Div of Clinical Immunology-Allergy; Dept of Medicine, UCLA School of Medicine; I Pozalski, MD, Cedars-Mt. Siani Hospital, Los Angeles; Field services Div, Epidemiology Program Office, CDC. First Encounter: Dr. Michael Gottleib http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/aids/view/ What is AIDS? Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome • Acquired means you can get infected with it (not inherited) • Immune Deficiency means a weakness in the body's system that fights diseases. • Syndrome means a group of health problems that make up a disease. The term AIDS refers to an advanced stage of HIV infection, when the immune system has sustained substantial damage. Not everyone who has HIV infection develops AIDS http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/fro ntline/aids/view/ Global Statics of HIV/AIDS Transmission of HIV “Patient Zero” and HIV Transmission Gaëtan Dugas: A Canadian who worked for Air Canada as a flight attendant Claimed to have had over 2,500 sexual partners across North America 1972 Diagnosed with Kaposi's Sarcoma in June 1980 In 1982 the CDC linked him to 9 of the first 19 cases in Los Born February 20, 1953 Angeles, 22 cases in NYC and 9 March 30, 1984 Died (aged 31) more in 8 other cities – Total of 40 Quebec City, Quebec of the first 248 cases in the U.S. Occupation Flight attendant New Model: HIV Traveled to Haiti, Then U.S. -

Where's the Cure?

A QUARTERLY JOURNAL ON HIV PREVENTION, TREATMENT AND POLITICS VOLUME 5, NO. 3 acHIeVe INSIDE Personal Perspective: CHANGING MY GENES 6 Where’s Being part of something as big as the search for the cure is a humbling experience. INCHING The TOWARD A VACCINE 9 The past two years Cure? have seen discover- ies that give hope that it may be possible to find an effective vaccine. THE FUTURE OF HIV PREVENTION 12 Three decades into the HIV epidemic, the A Look At Research number of new infections remains distress- ingly high. Across the U.S. HEPATITIS C: NEW DANGERS, that NIH granting procedures drastically NEW HOPES 16 by Stephen LeBlanc New information on slowed research and diverted money to transmission and a cure. university overhead costs, rather than to n 2009, Martin Delaney, a leading the search for a cure. Proponents esti- AIDS activist and the founder of Personal Perspective: mated a budget for the AIDS Cure Project Project Inform, co-authored an arti- MY FIGHT FOR A of $1.84 billion over five years. cle in Science calling for a new “HIV HEPATITIS C CURE 20 ICollaboratory” to focus on cure research. The Delaney Collaboratories The data on the new drug looked fabulous. The Collaboratory would be designed “to Nothing like the HIV Collaboratory or I thought, “I want this drug!” accelerate basic discovery and the clinical the AIDS Cure Project ever emerged, LOOKING BACK, translation of these discoveries.” Sadly, either in the amount of funding or in the LOOKING FOR- he died before the article was published. -

2016 Annual Report

June 12, 2017 Dear Friend of TAG: I’m so proud to share with you Treatment Action Group’s 2016 Annual Report. As you will see, TAG’s passionately dedicated, deeply informed staff have been unstinting in their efforts to speed up research and high-quality prevention, treatment, and care programs for people living with HIV, hepatitis C virus (HCV), or tuberculosis (TB), and for those most at risk of acquiring these infections. Today, more than ever, TAG’s work is vital. We are living Ending the in an unprecedented political era. Every day brings a new outrage and gathering threats to our work promoting research, prevention, and treatment. Everything TAG has fought for over the past three decades to defeat HIV/AIDS and end the TB and HCV Epidemic epidemics is at risk. Our progress towards ending these epidemics with Progress in the Fight extremely effective new tools for prevention, treatment, and cures will be in vain if people don’t have comprehensive for Better Treatment, coverage to ensure access. TAG’s vital work needs your support now more than ever: a Vaccine, and a • TAG is leading community efforts to end AIDS as an 2016 epidemic in New York State by the close of 2020 by Cure for AIDS Annual strengthening HIV, STD, and sexual health programs for Report those most affected • TAG is expanding its Ending the Epidemic work to southern states where the HIV/AIDS epidemic continues at its worst • TAG is leading efforts to build on existing law and regulation to control drug costs • TAG is leading efforts to defend key National Institutes of Health AIDS research agencies and their budgets from brutal cuts proposed by the new administration • TAG is fighting efforts to greatly weaken the U.S. -

Sharon Lewin

AIDS 2014 Key Media Coverage: HIV Cure 1 Key Media Coverage th 20 International AIDS Conference (AIDS 2014) Melbourne, Australia July 20-25, 2014 AIDS 2014 Key Media Coverage: HIV Cure 2 HIV Cure AIDS 2014. Melbourne, Australia A. Wire Reuters ............................................................................................................................................... 3 Bloomberg .......................................................................................................................................... 5 Agence France Press (AFP) .............................................................................................................. 10 Australian Associated Press (AAP) .................................................................................................. 12 Indo-Asian News Service ................................................................................................................. 13 B. Broadcast ABC RADIO ......................................................................................................................................... 18 9NEWS ............................................................................................................................................. 33 7NEWS ............................................................................................................................................. 33 C. Online media and blogs The Sydney Morning Herald ................................................................................................................. -

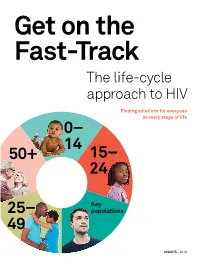

Get on the Fast-Track — the Life-Cycle Approach To

Get on the Fast-Track The life-cycle approach to HIV Finding solutions for everyone at every stage of life 0 – 14 50+ 1 5 – 24 Key 2 5 – populations 49 UNAIDS | 2016 2 contents 1 Foreword 3 2 Introduction 6 3 Children (0–14) 12 4 Young people (15–24) 28 5 Key populations throughout the life cycle 50 6 Adulthood (25–49) 72 7 Ageing (50+) 90 8 Conclusion 101 9 AIDS by the numbers 105 10 Annex on methods 133 2 foreword The scope of HIV prevention and treatment options has never been wider than it is today. The world now has the scientific knowledge and experience to reach people with HIV options tailored to their lives in the communities in which they live. This life-cycle approach to HIV ensures that we find the best solutions for people throughout their lifetime. And it begins with giving children a healthy start in life free from HIV. The progress made in reducing mother-to-child transmission of HIV is one of the remarkable success stories in global health. Antiretroviral medicines have averted 1.6 million new HIV infections among children since 2000. Even so, intensified efforts are needed to virtually eliminate transmis- sion from mother to child. Adolescence is a turbulent time, and a particularly dangerous time for young women living in sub-Saharan Africa. As they transition to adulthood, their risk of becoming infected with HIV increases dramatically. When women and girls are empowered, they have the means to protect themselves from becoming infected with HIV and to access HIV services. -

Editing a Cure

MILESTONES infection and prompted further research into gene-based therapies to genome editing target HIV. Although genome editing had had been been proven efficient in rendering proven efficient T cells refractory to HIV infection, in rendering it was not until years later, in 2014, T cells that a team led by Pablo Tebas and Carl June at the University of refractory to Pennsylvania in Philadelphia showed HIV infection this could be done in infected Credit: Bloomberg/Rob Waters via Getty Images Getty via Bloomberg/Rob Waters Credit: individuals. The clinical trial enrolled 12 patients who were infused with autologous CD4+ T cells modified at the CCR5 locus by zinc-finger nucleases (ZFNs). The patients who stopped ART after cell transfusion exhibited slow viral rebound and proliferation of the modified T cells, MILESTONE 18 indicating enhanced control of the virus. Moreover, one study participant with no viral rebound Editing a cure during ART interruption was found to harbor a single mutated copy of CCR5 and after transfusion a large Timothy Ray Brown—also known transplantation and interruption of proportion of this patient’s T cells as the ‘Berlin patient’—is the only antiretroviral therapy (ART). were resistant to HIV. person ever to be cured of HIV. His Although at the time of transplant Together, these findings story and the research that followed Brown also carried HIV variants demonstrated that gene-targeting are intimately linked to the discovery, tropic for the CXCR4 chemokine approaches could provide a safer back in 1996, that homozygosity for receptor, Hütter reasoned that their and more practical approach than a CCR5 allele with a 32-base-pair numbers might have been too low to the risky and restrictive HSCT and deletion (delta32/delta32) renders allow reseeding of the new immune opened the door for ZFNs and some individuals resistant to system. -

The First World AIDS Day

1 On June 5, 1981, the United States Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) issued its first warning about a relatively rare form of pneumonia among a small group of young gay men in Los Angeles, which was later deter- mined to be AIDS-related. Since that time, tens of millions of people have been infected with HIV worldwide. The Global HIV/AIDS Timeline is designed to serve as an ongoing reference tool for the many political, scientific, cultural, and community developments that have occurred over the history of the epidemic. Started in 1988, World AIDS Day is not just about raising money, but also about increasing awareness, fighting prejudice and improving education. World AIDS Day is important in reminding people that HIV has not gone away, and that there are many things still to be done. ~avert.org, 2006 2 While 1981 is generally referred to as the beginning of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, scientists believe that HIV was present years before the first case was brought to public attention. In 1959, The first known case of HIV in a human occurs in a person who died in the Congo, later confirmed as hav- ing HIV infection from his preserved blood samples. The authors of the study did not sequence a full virus from his samples, writing that "attempts to amplify HIV-1 fragments of >300 base pairs were unsuccessful, . Howev- er, after numerous attempts, four shorter sequences were obtained" that represented small portions of two of the six genes of the complete AIDS virus. In New York City, on June 28, 1959, Ardouin Antonio, a 49-year-old Jamaican-American shipping clerk dies of Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia, a disease closely associated with AIDS. -

HIV Eradication: Is Cord Blood the Answer?

Comment HIV eradication: is cord blood the answer? Since the fi rst reported case of long-term HIV-1 remission CCR5 Δ32 heterozygous donor were used to bridge the after allogeneic haemopoeitc stem cell transplantation time during cord blood engraftment. The authors also (HSCT) in 2007, the search for an HIV cure has remained showed that engrafted cord-blood-derived cells were elusive. Timothy Ray Brown, the Berlin Patient, received resistant to the recipient’s HIV strain. donor cells homozygous for a 32 base-pair deletion in Despite the loss of detectable cell-associated HIV CCR5, rendering them resistant to his HIV-1 strain.1,2 DNA and RNA, low-level plasma viraemia was detected Subsequent studies showed that allogeneic HSCT with 76 days after transplant. The source of this very low- CCR5 wild-type donor cells can substantially reduce the level viraemia is unclear as the participant died from HIV reservoir, even to the point of being undetectable by progressive lymphoma and was unable to have an BSIP Astier/Science Photo Library BSIP sensitive laboratory assays.3–8 However, two individuals analytical treatment interruption, the only defi nitive Lancet HIV 2015 who had analytical antiretroviral treatment interruption test for permanent HIV remission or cure. Nonetheless, Published Online had viral rebound despite undetectable virus in blood residual recipient haemopoietic cell activation and May 20, 2015 or gut-associated lymphoid tissue years after wild-type death might have been the source of the residual low- http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/ S2352-3018(15)00088-0 6 HSCT. Substantially delayed times to viral rebound were level plasma viremia, because de novo infection of See Online/Articles observed, suggesting that HIV can persist in very few donor CCR5 Δ32 cells was unlikely. -

Advances Toward a Cure for HIV: Getting Beyond N=2

Advances Toward Cure Volume 27 Issue 4 December 2019/January 2020 Perspective Advances Toward a Cure for HIV: Getting Beyond n=2 Achieving a cure for HIV remains a priority in HIV research. Two cases of ‘ster- long-term complications of HIV despite ilizing cure’ have been observed—in Timothy Ray Brown and the “London” ART, including evidence for accelerated patient; both patients received allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplan- aging and increased risks of cognitive tation (HSCT) from donors homozygous for the CCR5-delta 32 deletion, which dysfunction, cardiovascular disease, impairs function of an HIV coreceptor on host cells. Other strategies that have renal disease, and other complica- been evaluated for achieving sterilizing cure or functional cure—ie, sustained tions.3-6 All of these factors provide a virologic remission in the absence of antiretroviral therapy (ART)—include: strong rationale for pursuing cure for HSCT with wild-type CC chemokine receptor (CCR5); early ART to limit size HIV infection. of the HIV latent reservoir; shock and kill strategies using latency reversing agents and/or anti-HIV broadly neutralizing antibodies; and gene therapy, Mechanisms of HIV Persistence including attempts to modify CCR5 genes, HIV proviruses in autologous host cells, or enhanced T cells. This article summarizes a presentation by Jonathan Data from long-term follow-up of a co- Li, MD, MMSc, at the International Antiviral Society-USA (IAS-USA) continuing hort of patients on ART indicate that education program held in Atlanta, Georgia, in March 2019. the HIV reservoir, indicated by levels of HIV DNA in CD4+ cells and periph- Keywords: HIV cure, CCR5-delta 32 deletion, London patient, post-treatment eral blood mononuclear cells, initially controllers, early ART, shock and kill, gene therapy. -

Nutrition | Conference Update: ICAAC and IDSA

NutritioN | CoNference update: iCAAC aNd IDSa J a n u a r y + f ebruary 2012 Living on A PrAyer Can faith help sustain us when living with HIV? The hIV TreaTmenT & healTh Journal of TPAN COMPLERA is a prescription medicine used as a complete single-tablet regimen to treat HIV-1 in adults who have never taken HIV medicines before. COMPLERA does not cure HIV or AIDS or help prevent passing HIV to others. one The for me New COMPLERA A complete HIV treatment in only 1 pill a day. Ask your healthcare provider if it’s the one for you. Patient model. Pill shown is not actual size. INDICAINDICATIONTION DoDo not not take take COMPLERA COMPLERA if if you you are are taking taking the the following following medicines: medicines: BeforeBefore taking taking COMPLERA, COMPLERA, tell tell your your healthcare healthcare provider provider if if you: you: CommonCommon side side effects effects associated associated with with COMPLERA: COMPLERA: • •other other HIV HIV medicines medicines (COMPLERA (COMPLERA provides provides a a complete complete treatment treatment for for HIV HIV infection.) infection.) • •have have liver liver problems, problems, including including hepatitis hepatitis B B or or C C virus virus infection infection • • trouble trouble sleeping sleeping (insomnia), (insomnia), abnormal abnormal dreams, dreams, headache, headache, dizziness, dizziness, diarrhea, diarrhea, COMPLERACOMPLERA®® (emtricitabine (emtricitabine 200 200 mg/rilpivirine mg/rilpivirine 25 25 mg/tenofovir mg/tenofovir disoproxil disoproxil fumarate fumarate • • the