Molinism and Divine Aseity: a Review of Ontological Commitment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Anselmian Approach to Divine Simplicity

Faith and Philosophy: Journal of the Society of Christian Philosophers Volume 37 Issue 3 Article 3 7-1-2020 An Anselmian Approach to Divine Simplicity Katherin A. Rogers Follow this and additional works at: https://place.asburyseminary.edu/faithandphilosophy Recommended Citation Rogers, Katherin A. (2020) "An Anselmian Approach to Divine Simplicity," Faith and Philosophy: Journal of the Society of Christian Philosophers: Vol. 37 : Iss. 3 , Article 3. DOI: 10.37977/faithphil.2020.37.3.3 Available at: https://place.asburyseminary.edu/faithandphilosophy/vol37/iss3/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at ePLACE: preserving, learning, and creative exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faith and Philosophy: Journal of the Society of Christian Philosophers by an authorized editor of ePLACE: preserving, learning, and creative exchange. applyparastyle "fig//caption/p[1]" parastyle "FigCapt" applyparastyle "fig" parastyle "Figure" AQ1–AQ5 AN ANSELMIAN APPROACH TO DIVINE SIMPLICITY Katherin A. Rogers The doctrine of divine simplicity (DDS) is an important aspect of the clas- sical theism of philosophers like Augustine, Anselm, and Thomas Aquinas. Recently the doctrine has been defended in a Thomist mode using the intrin- sic/extrinsic distinction. I argue that this approach entails problems which can be avoided by taking Anselm’s more Neoplatonic line. This does involve AQ6 accepting some controversial claims: for example, that time is isotemporal and that God inevitably does the best. The most difficult problem involves trying to reconcile created libertarian free will with the Anselmian DDS. But for those attracted to DDS the Anselmian approach is worth considering. -

The Providence of God: a Trinitarian Perspective

The Providence of God: A Trinitarian Perspective Haydn D. Nelson BA DipEd BD(Hons) This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of Murdoch University 2005 I declare that this thesis is my own account of my research and contains as its main content work that has not previously been submitted for a degree at any tertiary education institution. ……………………………… Haydn D. Nelson ABSTRACT The primary focus of this dissertation is the doctrine of the Providence of God and it is approached from a distinctive perspective – that of the doctrine of the Trinity. Its fundamental thesis is that the adoption of a trinitarian perspective on Providence provides us with a conceptual paradigm in which varying theological emphases, which often divide understandings of Providence, are best understood in a form of paradoxical tension or creative balance with each being correctly understood only in the context that the other provides. To demonstrate this, it addresses four issues of Providence that have on occasion divided understandings of Providence in the past and which have become significant issues of contention in the contemporary debate on Providence occasioned by a proposal known as Open Theism. These issues concern the nature of divine transcendence, sovereignty, immutability and impassibility and how each should be understood in the context of divine Providence. Through a detailed examination of three recent trinitarian theologies, which have emanated from the three main communities of the Christian church, it argues that a trinitarian perspective is able to provide significant illumination and explication of these identified issues of Providence and of the tensions that are often intrinsic to this doctrine. -

A Critique of the Free Will Defense, a Comprehensive Look at Alvin Plantinga’S Solution to the Problem of Evil

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Honors Theses and Capstones Student Scholarship Spring 2013 A Critique of the Free Will Defense, A Comprehensive Look at Alvin Plantinga’s Solution To the Problem of Evil. Justin Ykema University of New Hampshire - Main Campus Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/honors Part of the Medieval Studies Commons, Philosophy Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Ykema, Justin, "A Critique of the Free Will Defense, A Comprehensive Look at Alvin Plantinga’s Solution To the Problem of Evil." (2013). Honors Theses and Capstones. 119. https://scholars.unh.edu/honors/119 This Senior Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses and Capstones by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. University of New Hampshire Department of Philosophy 2012-2013 A Critique of the Free Will Defense A Comprehensive Look at Alvin Plantinga’s Solution To the Problem of Evil. by Justin Ykema Primary Reader: Jennifer Armstrong Additional Readers: Willem deVries, Paul McNamara & Ruth Sample Graties tibi ago, domine. Haec credam a deo pio, a deo justo, a deo scito? Cruciatus in crucem. Tuus in terra servus, nuntius fui; officium perfeci. Cruciatus in crucem. Eas in crucem. 1 Section I: Introduction Historically, the problem of evil exemplifies an apparent paradox. The paradox is, if God exists, and he is all-good, all-knowing, and all-powerful, how does evil exist in the world when God created everything the world contains? Many theologians have put forth answers to solve this problem, and one of the proposed solutions put forth is the celebrated Free Will Defense, which claims to definitively solve the problem of evil. -

Theological Foundations Alternate Edition

Theological Foundations Alternate Edition REVISED AND EXPANDED J. J. Mueller, SJ, editor Created by the publishing team of Anselm Academic. Cover image of Jesus and five apostles by © Fotowan / shutterstock.com Copyright © 2007, 2011 by Anselm Academic, Christian Brothers Publications, 702 Terrace Heights, Winona, MN 55987-1320, www.anselmacademic.org. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced by any means without the written permission of the publisher. Printed in the United States of America 7036 ISBN 978-1-59982-134-4 ABOUT THE AUTHORS J. J. Mueller, SJ Maximilian Universität in Munich, Germany. Fr. Mueller holds a PhD in historical and sys- His interests are the study of St. Francis of tematic theology from the Graduate Theological Assisi, the Franciscan spiritual tradition, and the Union at Berkeley. His interests are Christology application of theology to social justice. and social responsibility. Ronald Modras Bernhard A. Asen Dr. Modras holds a doctorate in theology from Dr. Asen holds a PhD in biblical languages and the University of Tubingen in Germany. His literature from Saint Louis University. His par- interests include interreligious dialogue and ticular interests are the prophets and the Psalms. Jewish-Christian relations. James A. Kelhoffer John Renard Dr. Kelhoffer holds a PhD in New Testament Dr. Renard holds a PhD in Islamic studies from and early Christian literature from the Uni- the Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations versity of Chicago. His interests are the New Department of Harvard University. Since 1978, Testament and the early church. he has been teaching courses in Islam and other major non-Christian traditions as well as Brian D. -

Why Can't the Impassible God Suffer?

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by UCLouvain: Open Journal Repository (Université catholique de Louvain) 2018 TheoLogica An International Journal for Philosophy of Religion and Philosophical Theology S.I. NEW THEMES IN ANALYTIC DOGMATIC THEOLOGY DOI: https://doi.org/10.14428/thl.v0i0.1313 Why Can’t the Impassible God Suffer? Analytic Reflections on Divine Blessedness R.T. MULLINS University of St Andrews [email protected] Abstract: According to classical theism, impassibility is said to be systematically connected to divine attributes like timelessness, immutability, simplicity, aseity, and self-sufficiency. In some interesting way, these attributes are meant to explain why the impassible God cannot suffer. I shall argue that these attributes do not explain why the impassible God cannot suffer. In order to understand why the impassible God cannot suffer, one must examine the emotional life of the impassible God. I shall argue that the necessarily happy emotional life of the classical God explains why the impassible God cannot suffer. Keywords: Impassibility, Timelessness, Immutability, Simplicity, God Throughout most of the history of Christianity, the doctrine of divine impassibility has enjoyed wide assent. However, its role in systematic theology has waxed and waned in different eras. During the early Christological debates, impassibility was the default view. It played an influential role against Logos-sarx models of the incarnation as well as a role in late Arian arguments against the full divinity of Christ.1 Later generations, however, have not cast a favorable eye on impassibility. Before the turn of the 20th Century, various theologians began to endorse divine passibility in reaction to the unethical implications they perceived to be involved in the doctrine of divine impassibility. -

The Aseity of God

2 the Aseity of God Message introduction Of God’s many distinct attributes, one of the most difficult for finite human beings to come to terms with is His aseity, or self-existence. Unlike us, God has neither beginning nor end, and He is not dependent upon anyone or anything. In this mes- sage, as we consider God’s limitless abundance and our own neediness, Dr. Lawson invites us to seek full satisfaction and delight in the one who is the limitless source of all things. Scripture readingS Psalm 90:1–4; Romans 11:33–36; 1 Corinthians 8:5–6; Revelation 4:8 teaching obJectiveS 1. To discuss the implications of God’s eternal and self-sustaining nature 2. To recognize our inability to comprehend God’s boundless character 3. To invite Christians to take refuge in the all-sufficiency of God QuotationS There is something exceedingly improving to the mind in a contemplation of the Divinity. It is a subject so vast, that all our thoughts are lost in its immensity; so deep, that our pride is drowned in its infinity. Other subjects we can compass and grapple with; in them we feel a kind of self-content, and go our way with the thought, “Behold I am wise.” But when we come to this master-science, finding that our plumb-line cannot sound its depth, and that our eagle eye cannot see its height, we turn away . with the solemn exclamation, “I am but of yesterday, and know nothing.” —Charles Spurgeon 7 8 the attributes of god God was under no constraint, no obligation, no necessity to create. -

Divine Simplicity, Aseity, and Sovereignty

Divine Simplicity, Aseity, and Sovereignty Matthew Baddorf Sophia International Journal of Philosophy and Traditions ISSN 0038-1527 SOPHIA DOI 10.1007/s11841-016-0549-6 1 23 Your article is protected by copyright and all rights are held exclusively by Springer Science +Business Media Dordrecht. This e-offprint is for personal use only and shall not be self- archived in electronic repositories. If you wish to self-archive your article, please use the accepted manuscript version for posting on your own website. You may further deposit the accepted manuscript version in any repository, provided it is only made publicly available 12 months after official publication or later and provided acknowledgement is given to the original source of publication and a link is inserted to the published article on Springer's website. The link must be accompanied by the following text: "The final publication is available at link.springer.com”. 1 23 Author's personal copy SOPHIA DOI 10.1007/s11841-016-0549-6 Divine Simplicity, Aseity, and Sovereignty Matthew Baddorf1 # Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht 2016 Abstract The doctrine of divine simplicity has recently been ably defended, but very little work has been done considering reasons to believe God is simple. This paper begins to address this lack. I consider whether divine aseity (the traditionally prominent motivation) or the related notion of divine sovereignty provide us with good reason to affirm divine simplicity. Divine complexity has sometimes been thought to imply that God would possess an efficient cause; or, alternatively, that God would be grounded by God’s constituents. I argue that divine complexity implies neither of these, and so that a complex God could also exist ase. -

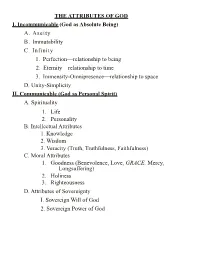

A. Aseity B. Immutability C. Infinity 1. Perfection—Relationship to Being 2. Eternity—Relationship to Time 3. Immensity-Omnipresence—Relationship to Space D

THE ATTRIBUTES OF GOD I. Incommunicable (God as Absolute Being) A. Aseity B. Immutability C. Infinity 1. Perfection—relationship to being 2. Eternity—relationship to time 3. Immensity-Omnipresence—relationship to space D. Unity-Simplicity II. Communicable (God as Personal Spirit) A. Spirituality 1. Life 2. Personality B. Intellectual Attributes 1. Knowledge 2. Wisdom 3. Veracity (Truth, Truthfulness, Faithfulness) C. Moral Attributes 1. Goodness (Benevolence, Love, GRACE, Mercy, Longsuffering) 2. Holiness 3. Righteousness D. Attributes of Sovereignty I. Sovereign Will of God 2. Sovereign Power of God THE GRACE OF GOD Grace IN God refers to God's unmerited love in action toward those who have forfeited it and deserve the very opposite, being under a sentence of condemnation. Because of this grace in God, we have Grace FROM God. God acts in grace (that is, He is gracious toward His own) because He is first of all a God of grace. God's grace is --Free: not prompted by anything outside of Himself --Spontaneous: self-generated, arising from a natural inclination --Not capricious: it is governed by His wisdom and will --Not with gain on the part of the Giver in mind --Not hindered by sin --Not conditioned upon works --Exclusive of merit on man's part ISRAEL'S RENEWAL—Ezekiel 36:16-32 Israel's sin and judgment :16-21 What the LORD will do to restore Israel: "I will . --sanctify My great name :23 --take you from among the nations :24 --gather you out of all countries --bring you into your own land --sprinkle clean water on you :25 --cleanse you from all your filthiness --cleanse you from all your idols --give you a new heart :26 --put a new spirit within you --take the stony heart out of your flesh --give you a heart of flesh --put My spirit within you :27 --cause you to walk in My statutes --be your God :28 --deliver you from all your uncleannesses :29 --call for the grain and multiply it --bring no famine upon you --multiply the fruit of your trees :30 --multiply the increase of your fields Why the LORD will do these things Negatively-- v. -

Divine Simplicity As a Necessary Condition for Affirming Creation Ex Nihilo

Abilene Christian University Digital Commons @ ACU Electronic Theses and Dissertations Electronic Theses and Dissertations 8-2019 Divine Simplicity as a Necessary Condition for Affirming eationCr Ex Nihilo Chance Juliano [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.acu.edu/etd Part of the Metaphysics Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Juliano, Chance, "Divine Simplicity as a Necessary Condition for Affirming eationCr Ex Nihilo" (2019). Digital Commons @ ACU, Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 160. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at Digital Commons @ ACU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ ACU. ABSTRACT Proponents of the Doctrine of Divine Simplicity (DDS) have frequently argued that God must lack any temporal, physical, or metaphysical composition on the grounds that God’s existence would be dependent upon God’s parts. This avenue of discourse has been tried and trod so often that most detractors of DDS find it insufficient to demonstrate DDS. Additionally, objectors to DDS have often rejected the doctrine on the count of the heap of metaphysical (often Aristotelian or Neoplatonist) assumptions that one must make before one can even arrive at DDS. Within this essay I will offer an argument for DDS that is advanced on the grounds of neither (1) arguing that a composite God’s existence would be dependent upon its parts and must be rejected, nor (2) made with a host of controversial metaphysical assumptions. -

8. the Attributes of God Herman Bavinck, Reformed Dogmatics, Vol. 2, Ch. 4

8. The attributes of God Herman Bavinck, Reformed Dogmatics , vol. 2, ch. 4 (pp. 148-177) Introduction We’re continuing with Herman Bavinck’s Reformed Dogmatics in session 8 of the Emmanuel Guided Reading Course, turning this time to the subject of God’s incommunicable attributes in volume 2, chapter 4. As you’ll have noticed last time, Bavinck writes pretty densely. But you will also have found that the time you spent chewing it over was very worthwhile. If you want candy floss, look elsewhere. But if you want a full roast dinner with all the trimmings, you’ve come to the right place. Here are a few ideas to help you follow the thread of what Bavinck is saying: • The questions have been divided up into sections corresponding with the major section headings in the chapter. There are also some brief summaries along the way to help you keep track of what Bavinck is saying. • The italic summary of the chapter on pp. 148-149, though not written by Bavinck himself, is nonetheless very helpful. Indeed, you might find it worth coming back to this as you read through the chapter, to keep the big picture in your mind. • If you find Bavinck’s writing a bit unmanageable, try breaking it down a little. You’ve got 4 hours to read 29 pages, and there are 9 questions below. So, every 25 minutes or so, you want to be answering one question and covering (on average) about 3 pages of reading. On this occasion, more of the questions for reflection are scattered throughout the study questions. -

God's Incommunicable Attributes by Herman Bavinck Scripture Itself Reveals the General Attributes of God's Nature Before, An

God’s Incommunicable Attributes by Herman Bavinck Scripture itself reveals the general attributes of God’s nature before, and more clearly than, it reveals his trinitarian existence. God is independent, all-sufficient in himself, and the only source of all existence and life. yhwh is the name that describes this essence and identity most clearly: “I will be what I will be.” It is in this aseity of God, conceived not only as having being from himself but also as the fullness of being, that all other divine perfections are included. Immutability is a natural implication of God’s aseity. While everything changes, God is and remains the same. If God were not immutable, he would not be God. To God alone belongs true being, and that which truly is remains. Contrary to both Deism and pantheism God who is cannot change, for every change would diminish his being. This doctrine of God’s immutability is important; the very distinction between Creator and creature hinges on the contrast between being and becoming. Our reliance on God depends on his immutability. Philosophic notions of absolute becoming have no place in Christian theology, nor should immutability be understood in static philosophic terms. The unchanging God is related to his creatures in manifold ways and participates in their lives. God is transcendent and immanent. Without losing himself he can give himself and, while absolutely maintaining his immutability, he can enter into an infinite number of relations to his creatures. When applied to time, God’s immutability (or infinity) is called eternity; when applied to space it is called omnipresence. -

The Doctrine of Prevenient Grace in the Theology of Jacobus Arminius

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Dissertations Graduate Research 2017 The Doctrine of Prevenient Grace in the Theology of Jacobus Arminius Abner F. Hernandez Andrews University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations Part of the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Hernandez, Abner F., "The Doctrine of Prevenient Grace in the Theology of Jacobus Arminius" (2017). Dissertations. 1670. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations/1670 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT THE DOCTRINE OF PREVENIENT GRACE IN THE THEOLOGY OF JACOBUS ARMINIUS by Abner F. Hernandez Fernandez Adviser: Jerry Moon ABSTRACT OF GRADUATE RESEARCH Dissertation Andrews University Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary Title: THE DOCTRINE OF PREVENIENT GRACE IN THE THEOLOGY OF JACOBUS ARMINIUS Name of researcher: Abner F. Hernandez Fernandez Name and degree of faculty adviser: Jerry Moon, Ph.D. Date completed: April 2017 Topic This dissertation addresses the problem of the lack of agreement among interpreters of Arminius concerning the nature, sources, development, and roles of prevenient grace in Arminius’s soteriology. Purpose The dissertation aims to investigate, analyze, and define the probable sources, nature, development, and role of the concept of prevenient or “preceding” grace in the theology of Jacobus Arminius (1559–1609). Sources The dissertation relies on Arminius’s own writings, mainly the standard London Edition, translated by James Nichols and Williams Nichols.