This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Soldier Fights for Three Separate but Sometimes Associated Reasons: for Duty, for Payment and for Cause

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Stirling Online Research Repository The press and military conflict in early modern Scotland by Alastair J. Mann A soldier fights for three separate but sometimes associated reasons: for duty, for payment and for cause. Nathianiel Hawthorne once said of valour, however, that ‘he is only brave who has affections to fight for’. Those soldiers who are prepared most readily to risk their lives are those driven by political and religious passions. From the advent of printing to the present day the printed word has provided governments and generals with a means to galvanise support and to delineate both the emotional and rational reasons for participation in conflict. Like steel and gunpowder, the press was generally available to all military propagandists in early modern Europe, and so a press war was characteristic of outbreaks of civil war and inter-national war, and thus it was for those conflicts involving the Scottish soldier. Did Scotland’s early modern soldiers carry print into battle? Paul Huhnerfeld, the biographer of the German philosopher and Nazi Martin Heidegger, provides the curious revelation that German soldiers who died at the Russian front in the Second World War were to be found with copies of Heidegger’s popular philosophical works, with all their nihilism and anti-Semitism, in their knapsacks.1 The evidence for such proximity between print and combat is inconclusive for early modern Scotland, at least in any large scale. Officers and military chaplains certainly obtained religious pamphlets during the covenanting period from 1638 to 1651. -

S39169 Samuel Baker

Southern Campaigns American Revolution Pension Statements & Rosters Pension application of Samuel Baker S39169 f26NC Transcribed by Will Graves 1/6/08 rev'd 8/8/14 [Methodology: Spelling, punctuation and/or grammar have been corrected in some instances for ease of reading and to facilitate searches of the database. Where the meaning is not compromised by adhering to the spelling, punctuation or grammar, no change has been made. Corrections or additional notes have been inserted within brackets or footnotes. Blanks appearing in the transcripts reflect blanks in the original. A bracketed question mark indicates that the word or words preceding it represent(s) a guess by me. The word 'illegible' or 'indecipherable' appearing in brackets indicates that at the time I made the transcription, I was unable to decipher the word or phrase in question. Only materials pertinent to the military service of the veteran and to contemporary events have been transcribed. Affidavits that provide additional information on these events are included and genealogical information is abstracted, while standard, 'boilerplate' affidavits and attestations related solely to the application, and later nineteenth and twentieth century research requests for information have been omitted. I use speech recognition software to make all my transcriptions. Such software misinterprets my southern accent with unfortunate regularity and my poor proofreading skills fail to catch all misinterpretations. Also, dates or numbers which the software treats as numerals rather than -

“For Christ and Covenant:” a Movement for Equal Consideration in Early Nineteenth Century Nova Scotia

“For Christ and Covenant:” A Movement for Equal Consideration in Early Nineteenth Century Nova Scotia. By Holly Ritchie A Thesis Submitted to Saint Mary’s University, Halifax, Nova Scotia in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in History © Copyright Holly Ritchie, 2017 November, 2017, Halifax, Nova Scotia Approved: Dr. S. Karly Kehoe Supervisor Approved: Dr. John Reid Reader Approved: Dr. Jerry Bannister Examiner Date: 30 November 2017 1 Abstract “For Christ and Covenant:” A Movement for Equal Consideration in Early Nineteenth Century Nova Scotia. Holly Ritchie Reverend Dr. Thomas McCulloch is a well-documented figure in Nova Scotia’s educational historiography. Despite this, his political activism and Presbyterian background has been largely overlooked. This thesis offers a re-interpretation of the well-known figure and the Pictou Academy’s fight for permeant pecuniary aid. Through examining Scotland’s early politico-religious history from the Reformation through the Covenanting crusades and into the first disruption of the Church of Scotland, this thesis demonstrates that the language of political disaffection was frequently expressed through the language of religion. As a result, this framework of response was exported with the Scottish diaspora to Nova Scotia, and used by McCulloch to stimulate a movement for equal consideration within the colony. Date: 30 November 2017 2 Acknowledgements Firstly, to the wonderful Dr. S. Karly Kehoe, thank you for providing me with an opportunity beyond my expectations. A few lines of acknowledgement does not do justice to the impact you’ve had on my academic work, and my self-confidence. -

The Church Militant: the American Loyalist Clergy and the Making of the British Counterrevolution, 1701-92

The Church Militant: The American Loyalist Clergy and the Making of the British Counterrevolution, 1701-92 Peter W. Walker Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2016 © 2016 Peter Walker All rights reserved ABSTRACT The Church Militant: The American Loyalist Clergy and the Making of the British Counterrevolution, 1701-92 Peter W. Walker This dissertation is a study of the loyalist Church of England clergy in the American Revolution. By reconstructing the experience and identity of this largely-misunderstood group, it sheds light on the relationship between church and empire, the role of religious pluralism and toleration in the American Revolution, the dynamics of loyalist politics, and the religious impact of the American Revolution on Britain. It is based primarily on the loyalist clergy’s own correspondence and writings, the records of the American Loyalist Claims Commission, and the archives of the SPG (the Church of England’s missionary arm). The study focuses on the New England and Mid-Atlantic colonies, where Anglicans formed a religious minority and where their clergy were overwhelmingly loyalist. It begins with the founding of the SPG in 1701 and its first forays into America. It then examines the state of religious pluralism and toleration in New England, the polarising contest over the proposed creation of an American bishop after the Seven Years’ War, and the role of the loyalist clergy in the Revolutionary War itself, focusing particularly on conflicts occasioned by the Anglican liturgy and Book of Common Prayer. -

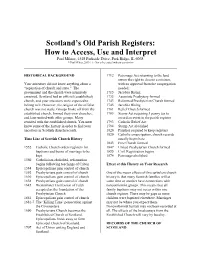

Scotland's Old Parish Registers: How to Access, Use and Interpret

Scotland’s Old Parish Registers: How to Access, Use and Interpret Paul Milner, 1548 Parkside Drive, Park Ridge, IL 6068 © Paul Milner, 2003-11 - Not to be copied without permission HISTORICAL BACKGROUND 1712 Patronage Act returning to the land owner the right to choose a minister, Your ancestors did not know anything about a with no approval from the congregation “separation of church and state.” The needed. government and the church were intimately 1715 Jacobite Rising entwined. Scotland had an official (established) 1733 Associate Presbytery formed church, and your ancestors were expected to 1743 Reformed Presbyterian Church formed belong to it. However, the religion of the official 1745 Jacobite Rising church was not static. Groups broke off from the 1761 Relief Church formed established church, formed their own churches, 1783 Stamp Act requiring 3 penny tax to and later united with other groups. Many record an event in the parish register reunited with the established church. You must 1793 Catholic Relief Act know some of the history in order to find your 1794 Stamp Act abolished ancestors in Scottish church records. 1820 Parishes required to keep registers 1829 Catholic emancipation, church records Time Line of Scottish Church History usually begin here 1843 Free Church formed 1552 Catholic Church orders registers for 1847 United Presbyterian Church formed baptisms and banns of marriage to be 1855 Civil Registration begins kept 1874 Patronage abolished 1560 Catholicism abolished, reformation begins following teachings of Calvin Effect of this History on Your Research 1584 Episcopalians gain control of church 1592 Presbyterians gain control of church One of the major effects of this turbulent church 1610 Episcopalians gain control of church history is that many Scottish families will at 1638 Presbyterians gain control of church some time or another have connections with 1645 Westminster Confession of Faith nonconformist groups. -

"For the Advancement of So Good a Cause": Hugh Mackay, the Highland War and the Glorious Revolution in Scotland

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 4-2012 "For the Advancement of So Good a Cause": Hugh MacKay, the Highland War and the Glorious Revolution in Scotland Andrew Phillip Frantz College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Frantz, Andrew Phillip, ""For the Advancement of So Good a Cause": Hugh MacKay, the Highland War and the Glorious Revolution in Scotland" (2012). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 480. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/480 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF SO GOOD A CAUSE”: HUGH MACKAY, THE HIGHLAND WAR AND THE GLORIOUS REVOLUTION IN SCOTLAND A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts with Honors is History from the College of William and Mary in Virginia, by Andrew Phillip Frantz Accepted for ___________________________________ (Honors, High Honors, Highest Honors) _________________________________________ Nicholas Popper, Director _________________________________________ Paul Mapp _________________________________________ Simon Stow Williamsburg, Virginia April 30, 2012 Contents Figures iii Acknowledgements iv Introduction 1 Chapter I The Origins of the Conflict 13 Chapter II Hugh MacKay and the Glorious Revolution 33 Conclusion 101 Bibliography 105 iii Figures 1. General Hugh MacKay, from The Life of Lieutenant-General Hugh MacKay (1836) 41 2. The Kingdom of Scotland 65 iv Acknowledgements William of Orange would not have been able to succeed in his efforts to claim the British crowns if it were not for thousands of people across all three kingdoms, and beyond, who rallied to his cause. -

Christopher Upton Phd Thesis

?@A374? 7; ?2<@@7?6 81@7; 2IQJRSOPIFQ 1$ APSON 1 @IFRJR ?TCMJSSFE GOQ SIF 3FHQFF OG =I3 BS SIF ANJUFQRJSX OG ?S$ 1NEQFVR '.-+ 5TLL MFSBEBSB GOQ SIJR JSFM JR BUBJLBCLF JN >FRFBQDI0?S1NEQFVR/5TLL@FWS BS/ ISSP/%%QFRFBQDI#QFPORJSOQX$RS#BNEQFVR$BD$TK% =LFBRF TRF SIJR JEFNSJGJFQ SO DJSF OQ LJNK SO SIJR JSFM/ ISSP/%%IEL$IBNELF$NFS%'&&()%(,)* @IJR JSFM JR PQOSFDSFE CX OQJHJNBL DOPXQJHIS STUDIES IN SCOTTISH LATIN by Christopher A. Upton Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of St. Andrews October 1984 ýýFCA ýý£ s'i ý`q. q DRE N.6 - Parentibus meis conjugique meae. Iý Christopher Allan Upton hereby certify that this thesis which is approximately 100,000 words in length has been written by men that it is the record of work carried out by me and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for a higher degree. ý.. 'C) : %6 date .... .... signature of candidat 1404100 I was admitted as a research student under Ordinance No. 12 on I October 1977 and as a candidate for the degree of Ph. D. on I October 1978; the higher study for which this is a record was carried out in the University of St Andrews between 1977 and 1980. $'ý.... date . .. 0&0.9 0. signature of candidat I hereby certify that the candidate has fulfilled the conditions of the Resolution and Regulations appropriate to the degree of Ph. D. of the University of St Andrews and that he is qualified to submit this thesis in application for that degree. -

13 Ii C? :.Sjoj«I

.13 ii c? :.SjOJ«i LI.' mi iaOTffi?a "i,r(:HiR.J> §& co'fiisb C s£ "C’ O 'V S o c £cf -O- Ses. § is. 12^ PUBLICATIONS OF THE SCOTTISH HISTORY SOCIETY THIRD SERIES VOLUME X LI I ACCOUNTS OF THE COLLECTORS OF THIRDS OF BENEFICES 1561-1572 1949 ACCOUNTS OF THE COLLECTORS OF THIRDS OF BENEFICES 1561-1572 Edited by GORDON DONALDSON, Ph.D. EDINBURGH Printed by T. and A. Constable Ltd. Printers to the University of Edinburgh for the Scottish History Society 1949 Printed in Great Britain CONTENTS PAGE Introduction ....... vii Charge of Thirds, 1561-1572 .... 1 Account of the Collector General, 1561 . 45 Account of the Collector General, 1562 . 120 Accounts of the Collector General, 1563-1568 172 Abstracts of Accounts of Sub-Collectors, 1563-1572 :— Orkney and Shetland ..... 202 Inverness, etc. ‘ • • • • 205 Moray . 211 Aberdeen and Banff . .218 Forfar and Kincardine ..... 227 Fife, Fothrik and Kinross .... 237 Perth and Strathearn ..... 247 Stirling, Dumbarton, Renfrew, Lanark, Kyle, Garrick and Cunningham .... 256 Edinburgh, Linlithgow, Haddington and Berwick 271 Roxburgh, Berwick, Selkirk and Peebles . 280 Dumfries, Annandale, Kirkcudbright and Wig- town ....... 286 Index 298 A generous contribution from the Carnegie Trust for the Universities of Scotland towards the cost of producing this volume is gratefully acknowledged by the Council of the Society. INTRODUCTION Any statesmanlike and practicable attempt to settle the disposition of the property of the Scottish church at the Reformation had to take into account not only the financial needs of the protestant congregations but also the compet- ing claims of the crown, the beneficed clergy, the nobility and the gentry to share in the ecclesiastical wealth. -

55 5. WOIDERFIL PROPHECIES Or DONALD CARGILL, Who Was

55 5. WOIDERFIL PROPHECIES or DONALD CARGILL, Who was executed at the Cross of Edinburgh, on the 23d July, 1680. For his adherence to the Covenant and Work of REFORM ATI OiS. DUMFRIES: PRINTED FOR THE BOOKSELLERS. RBK THE LIFE OF MR BOXALD CARCILL. 1.Ir Cargill, seems to have been born some time ibout the year )6l0. He was eldest son of a most espected family in the parish of Rattray. After he ;ad been some time in the schools of Aberdeen, he vent to St. Andrew’s, where having perfected his ourse of philosophy, his father pressed upon him nuen to study divinity, in order for the ministry; '“t he thought the work was to great for his weak boulders, and requested to command him to any they employment he pleased. But his father still ontinuing to urge him, he resolved to set apart a day f private fasting, to seek the Lord’s mind therein, md after much wrestlings with the Lord by prayer, le third chapter of Ezekial, and chiefly these words i the first verse. •• Son of man, eat this roll and p speak unto the house of Israel,” made a strong p pres si on on his mind, so that he durst no longer ;fuse his father’s desire, but dedicated himself holly unto that office. After this, he got a call to the Barony Church of dasgow. It was so ordered by Divine providence, 4- that the very first text that the presbytery ordered him to preach upon, was these words in the third of Ezekial, already mentioned, by which he was more confirmed, that he had God’s call to this parish. -

127179758.23.Pdf

—>4/ PUBLICATIONS OF THE SCOTTISH HISTORY SOCIETY THIRD SERIES VOLUME II DIARY OF GEORGE RIDPATH 1755-1761 im DIARY OF GEORGE RIDPATH MINISTER OF STITCHEL 1755-1761 Edited with Notes and Introduction by SIR JAMES BALFOUR PAUL, C.V.O., LL.D. EDINBURGH Printed at the University Press by T. A. Constable Ltd. for the Scottish History Society 1922 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION DIARY—Vol. I. DIARY—You II. INDEX INTRODUCTION Of the two MS. volumes containing the Diary, of which the following pages are an abstract, it was the second which first came into my hands. It had found its way by some unknown means into the archives in the Offices of the Church of Scotland, Edinburgh ; it had been lent about 1899 to Colonel Milne Home of Wedderburn, who was interested in the district where Ridpath lived, but he died shortly after receiving it. The volume remained in possession of his widow, who transcribed a large portion with the ultimate view of publication, but this was never carried out, and Mrs. Milne Home kindly handed over the volume to me. It was suggested that the Scottish History Society might publish the work as throwing light on the manners and customs of the period, supplementing and where necessary correcting the Autobiography of Alexander Carlyle, the Life and Times of Thomas Somerville, and the brilliant, if prejudiced, sketch of the ecclesiastical and religious life in Scotland in the eighteenth century by Henry Gray Graham in his well-known work. When this proposal was considered it was found that the Treasurer of the Society, Mr. -

The History of Cedarville College

Cedarville University DigitalCommons@Cedarville Faculty Books 1966 The iH story of Cedarville College Cleveland McDonald Cedarville University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/faculty_books Part of the Nonfiction Commons Recommended Citation McDonald, Cleveland, "The iH story of Cedarville College" (1966). Faculty Books. 65. http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/faculty_books/65 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Cedarville, a service of the Centennial Library. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Books by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Cedarville. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The iH story of Cedarville College Disciplines Creative Writing | Nonfiction Publisher Cedarville College This book is available at DigitalCommons@Cedarville: http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/faculty_books/65 CHAPTER I THE COVENANTERS Covenanters in Scotland. --The story of the Reformed Presby terians who began Cedarville College actually goes back to the Reformation in Scotland where Presbyterianism supplanted Catholicism. Several "covenants" were made during the strug gles against Catholicism and the Church of England so that the Scottish Presbyterians became known as the "covenanters." This was particularly true after the great "National Covenant" of 1638. 1 The Church of Scotland was committed to the great prin ciple "that the Lord Jesus Christ is the sole Head and King of the Church, and hath therein appointed a government distinct from that of the Civil magistrate. "2 When the English attempted to force the Episcopal form of Church doctrine and government upon the Scottish people, they resisted it for decades. The final ten years of bloody persecution and revolution were terminated by the Revolution Settlement of 1688, and by an act of Parliament in 1690 that established Presbyterianism in Scotland. -

W6757 William Crye

Southern Campaign American Revolution Pension Statements & Rosters Pension application of William Crye W6757 Sarah fn29SC Transcribed by Will Graves rev'd 6/9/11 [Methodology: Spelling, punctuation and/or grammar have been corrected in some instances for ease of reading and to facilitate searches of the database. Where the meaning is not compromised by adhering to the spelling, punctuation or grammar, no change has been made. Corrections or additional notes have been inserted within brackets or footnotes. Blanks appearing in the transcripts reflect blanks in the original. A bracketed question mark indicates that the word or words preceding it represent(s) a guess by me. Only materials pertinent to the military service of the veteran and to contemporary events have been transcribed. Affidavits that provide additional information on these events are included and genealogical information is abstracted, while standard, 'boilerplate' affidavits and attestations related solely to the application, and later nineteenth and twentieth century research requests for information have been omitted. I use speech recognition software to make all my transcriptions. Such software misinterprets my southern accent with unfortunate regularity and my poor proofreading fails to catch all misinterpretations. Also, dates or numbers which the software treats as numerals rather than words are not corrected: for example, the software transcribes "the eighth of June one thousand eighty six" as "the 8th of June 1786." Please call errors or omissions to my attention.] State of Tennessee, County of McMinn On this 4th day of June personally appeared in open Court, before the Justice of the County Court of said County, William Crye, a resident of said County and State, aged about Seventy nine years, who being first duly sworn according to law, doth, on his oath, make the following declaration, in order to obtain the benefit of the act of Congress, passed June 7, 1832.