THOMAS ADبS List of Works

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

POWDER-HER-FACE.Pdf

3 La Fenice prima dell’Opera 2012 3 2012 Fondazione Stagione 2012 Teatro La Fenice di Venezia Lirica e Balletto Thomas Adès Powder ace her f ace er InciprialeF h il viso owder owder p dès a homas t FONDAZIONE TEATRO LA FENICE DI VENEZIA TEATRO LA FENICE - pagina ufficiale seguici su facebook e twitter follow us on facebook and twitter FONDAZIONE TEATRO LA FENICE DI VENEZIA Destinare il cinque per mille alla cultura è facile e non costa nulla. Quando compili la tua dichiarazione dei redditi, indica il codice fiscale della Fondazione Teatro La Fenice di Venezia: 00187480272 Aiuti la cultura, aiuti la musica. Incontro con l’opera FONDAZIONE lunedì 16 gennaio 2012 ore 18.00 AMICI DELLA FENICE SANDRO CAPPELLETTO, MARIO MESSINIS, DINO VILLATICO STAGIONE 2012 Lou Salomé sabato 4 febbraio 2012 ore 18.00 MICHELE DALL’ONGARO L’inganno felice mercoledì 8 febbraio 2012 ore 18.00 LUCA MOSCA Così fan tutte martedì 6 marzo 2012 ore 18.00 LUCA DE FUSCO, GIANNI GARRERA L’opera da tre soldi martedì 17 aprile 2012 ore 18.00 LORENZO ARRUGA La sonnambula lunedì 23 aprile 2012 ore 18.00 PIER LUIGI PIZZI, PHILIP WALSH Powder Her Face giovedì 10 maggio 2012 ore 18.00 RICCARDO RISALITI La bohème lunedì 18 giugno 2012 ore 18.00 GUIDO ZACCAGNINI Carmen giovedì 5 luglio 2012 ore 18.00 MICHELE SUOZZO L’elisir d’amore giovedì 13 settembre 2012 ore 18.00 MASSIMO CONTIERO Clavicembalo francese a due manuali copia dello Rigoletto strumento di Goermans-Taskin, costruito attorno sabato 6 ottobre 2012 ore 18.00 alla metà del XVIII secolo (originale presso la Russell PHILIP GOSSETT Collection di Edimburgo). -

THOMAS ADÈS Works for Solo Piano

THOMAS ADÈS Works for Solo Piano Han Chen Thomas Adès (b. 1971) Works for Solo Piano Composer, conductor and pianist Thomas Adès has been sexual exploits scandalised Britain in the 1960s. Adès’s A set of five variants on the Ladino folk tune, ‘Lavaba la Written in 2009 to mark the Chopin bicentenary, the described by The New York Times as ‘among the most Concert Paraphrase on Powder Her Face (2009) reflects blanca niña’, Blanca Variations (2015) was commissioned three Mazurkas, Op. 27 (2009) were requested by accomplished all-round musicians of his generation’. Born the extravagance, grace and glamour of its subject in a by the 2016 Clara Haskil International Piano Competition. Emanuel Ax, who premiered them at Carnegie Hall, New in London in 1971, he studied piano at the Guildhall bravura piece in the grand manner of operatic paraphrases The music appears in Act I of The Exterminating Angel , York on 10 February 2010. The archetypal rhythms, School of Music & Drama, and read music at King’s of Liszt and Busoni. The composer quotes and Adès’s opera based on the film by Luis Buñuel, where it is ornamentation and phrasings of the dance form are College Cambridge. His music embraces influences from extemporises freely on several key scenes, transcribing performed by famous pianist Blanca Delgado. The wistful, evident in each of these tributes to the Polish master, yet jazz and pop as well as the Western classical tradition. He them as four spontaneous-sounding piano pieces. The first yearning folk tune persists throughout a varied sequence of Adès refashions such familiar gestures to create has contributed successfully to the major time-honoured piece is Scene One of the opera, Adès’s Ode to Joy (‘Joy’ treatments, some exploiting the full gamut of the keyboard something new and deeply personal. -

Debut Concert

PERFORMERS Timothy Steeves, violin Dian Zhang, violin Jarita Ng, viola Jakob Nierenz, cello Austin Lewellen, double bass Christina Hughes, flute and piccolo DEBUT CONCERT Katie Hart, oboe and english horn Thomas Frey, clarinet and bass clarinet Ben Roidl-Ward, bassoon and contrabassoon Michael Chen, trumpet (Mazzoli only) Daniel Egan, trumpet Daniel Hawkins, horn Tanner Antonetti, trombone Craig Hauschildt, percussion (Norman and Cerrone) Brandon Bell, percussion (Norman and Adès) Yvonne Chen,! piano Tuesday, December 6, 2016 Led by conductor, Jerry Hou 7:30pm ! SPECIAL THANKS TO Gallery at MATCH Ally Smither, Loop38 singer and staff Ling Ling Huang, Loop38 violinist and staff 3400 Main Street Fran Schmidt, recording Brian Hodge, Anthony Brandt, and Chloe Jolly, Musiqa Houston, TX 77002 Scuffed Shoe ! Lynn Lane Photography ! ! MORE INFO AT ! WWW.LOOP38.ORG new music in the heart of Houston www.loop38.org /Loop38 /instaloop38 /Loop38music PROGRAM Living Toys (1993) Thomas Adès (b.1971) Try (2011) Andrew Norman (b.1979) 18 min. 14 min. I. Angels Winner of the 2016 Grawemeyer Award, Andrew Norman is a Los Angeles- II. Aurochs based composer whose work draws on an eclectic mix of sounds and -BALETT- notational practices from both the avant-garde and classical traditions. He is III. Militiamen increasingly interested in story-telling in music, specifically in the ways non- linear, narrative-scrambling techniques from other time-based media like movies IV. H.A.L.’s Death and video games might intersect with traditional symphonic forms. -BATTLE- V. Playing Funerals Recovering (2011/12) Christopher Cerrone (b.1984) -TABLET- 8 min. “When the men asked him what he wanted to be, the child did not name any of Brooklyn-based composer Christopher Cerrone is internationally acclaimed for their own occupations, as they had all hoped he would, but replied: ‘I am going music which ranges from opera to orchestral, from chamber music to electronic. -

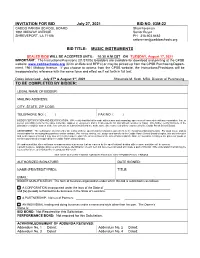

03M-22 – Music Instruments

INVITATION FOR BID July 27, 2021 BID NO. 03M-22 CADDO PARISH SCHOOL BOARD Shari Foreman 1961 MIDWAY AVENUE Senior Buyer SHREVEPORT, LA 71108 PH: 318.603.6482 [email protected] BID TITLE: MUSIC INSTRUMENTS SEALED BIDS WILL BE ACCEPTED UNTIL: 10:30 A.M.CST ON TUESDAY, August 17, 2021 IMPORTANT: The Instructions/Provisions (01/31/05) to bidders are available for download and printing at the CPSB website: www.caddoschools.org (Click on Bids and RFP’s) or may be picked up from the CPSB Purchasing Depart- ment, 1961 Midway Avenue. If you choose to access from the CPSB website, the Instructions/Provisions will be incorporated by reference with the same force and effect as if set forth in full text. Dates Advertised: July 27th & August 3rd, 2021 Shavonda M. Scott, MBA, Director of Purchasing TO BE COMPLETED BY BIDDER: LEGAL NAME OF BIDDER: MAILING ADDRESS: CITY, STATE, ZIP CODE: TELEPHONE NO: ( ) FAX NO: ( ) BIDDER CERTIFICATION AND IDENTIFICATION: I/We certify that this bid is made without prior understanding, agreement of connection with any corporation, firm, or person submitting a bid for the same materials, supplies or equipment, and is in all respects fair and without collusion or fraud. I/We further certify that none of the principals or majority owners of the firm or business submitting this bid are at the same time connected with or employed by the Caddo Parish School Board. ASSIGNMENT: The submission of a bid under the terms of these specifications constitutes agreement to the following antitrust provision: For good cause and as consideration for executing this purchase and/or contract, I/we hereby convey, sell, assign and transfer to the Caddo Parish School Board all rights, title and interest in and to all causes of action it may now or hereafter acquire under the antitrust laws of the United States and the State of Louisiana, relating to the particular goods or services purchased or acquired by the Caddo Parish School Board. -

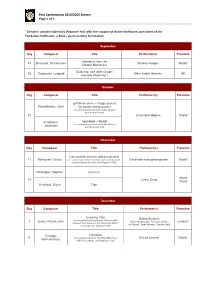

Past Commissions 2014/15

Past Commissions 2014/2015 Season Page 1 of 5 * Denotes commissioned by Wigmore Hall with the support of André Hoffmann, president of the Fondation Hoffmann, a Swiss grant-making foundation September Day Composer Title Performer(s) Première Variations from the 14 Birtwistle, Sir Harrison Nicolas Hodges World* Golden Mountains Study No. 44A after Chopin 15 Godowsky, Leopold Marc-André Hamelin UK nouvelle étude No.1 October Day Composer Title Performer(s) Première gefährlich dünn — fragile pieces Petraškevičs, Jānis for double string quartet (co-commissioned by Ensemble Modern and Wigmore Hall) 10 Ensemble Modern World* Schöllhorn, sous-bois – Sextet (co-commissioned by Ensemble Modern Johannes and Wigmore Hall) November Day Composer Title Performer(s) Première Carnaval for clarinet, piano and cello 11 Mantovani, Bruno (co-commissioned by Ensemble intercontemporain, Ensemble intercontemporain World* Opéra national de Paris and Wigmore Hall) Montague, Stephen nun-mul World 16 Jenna Sung World Pritchard, Gwyn Tide December Day Composer Title Performer(s) Première Uncanny Vale Britten Sinfonia (co-commissioned by Britten Sinfonia with 3 Jones, Patrick John (Emer McDonough, Nicholas Daniel, London* support from donors to the Musically Gifted Joy Farrall, Sarah Burnett, Stephen Bell) campaign and Wigmore Hall) Turnage, Contusion 6 (co-commissioned by The Radcliffe Trust, Belcea Quartet World* Mark-Anthony NMC Recordings and Wigmore Hall) Past Commissions 2014/2015 Season Page 2 of 5 January Day Composer Title Performer(s) Première Light and Matter Britten Sinfonia (co-commissioned by Britten Sinfonia with 14 Saariaho, Kaija (Jacqueline Shave, Caroline Dearnley, London* support from donors to the Musically Gifted campaign Huw Watkins) and Wigmore Hall) 3rd Quartet Holt, Simon (co-commissioned by The Radcliffe Trust, World* NMC Recordings, Heidelberger Frühling, and 19 Wigmore Hall) JACK Quartet Haas, Georg Friedrich String Quartet No. -

February 15, 2013

February 15, 2013 The New York Times Replica Edition - The New York Times - 15 Feb 2013 - Page #69 2/15/13 1:14 PM http://nytimes.newspaperdirect.com/epaper/services/OnlinePrintHandler.ashx?issue=83022013021500000000001001&page=69&paper=A3 Page 1 of 1 February 18, 2013 The New York Times Replica Edition - The New York Times - 18 Feb 2013 - Page #30 2/19/13 12:40 PM http://nytimes.newspaperdirect.com/epaper/services/OnlinePrintHandler.ashx?issue=83022013021800000000001001&page=30&paper=A3 Page 1 of 1 The New York Times Replica Edition - The New York Times - 10 Feb 2013 - Page #39 2/12/13 12:10 PM February 10, 2013 The New York Times Replica Edition - The New York Times - 10 Feb 2013 - Page #39 2/12/13 12:10 PM http://nytimes.newspaperdirect.com/epaper/services/OnlinePrintHandler.ashx?issue=83022013021000000000001001&page=39&paper=A3 Page 1 of 1 http://nytimes.newspaperdirect.com/epaper/services/OnlinePrintHandler.ashx?issue=83022013021000000000001001&page=39&paper=A3 Page 1 of 1 February 19, 2013 New Approaches to Themes Sacred and Sexual | Parsifal | Powder Her Face | Opera Reviews by Heidi Waleson - WSJ.com 3/2/13 12:44 PM Dow Jones Reprints: This copy is for your personal, non-commercial use only. To order presentation-ready copies for distribution to your colleagues, clients or customers, use the Order Reprints tool at the bottom of any article or visit www.djreprints.com See a sample reprint in PDF format. Order a reprint of this article now OPERA February 19, 2013, 6:00 p.m. ET New Approaches to Themes Sacred and Sexual By HEIDI WALESON Ken Howard/Metropolitan Opera Director François Girard transports Wagner's final opera to a postapocalyptic period. -

Navigating, Coping & Cashing In

The RECORDING Navigating, Coping & Cashing In Maze November 2013 Introduction Trying to get a handle on where the recording business is headed is a little like trying to nail Jell-O to the wall. No matter what side of the business you may be on— producing, selling, distributing, even buying recordings— there is no longer a “standard operating procedure.” Hence the title of this Special Report, designed as a guide to the abundance of recording and distribution options that seem to be cropping up almost daily thanks to technology’s relentless march forward. And as each new delivery CONTENTS option takes hold—CD, download, streaming, app, flash drive, you name it—it exponentionally accelerates the next. 2 Introduction At the other end of the spectrum sits the artist, overwhelmed with choices: 4 The Distribution Maze: anybody can (and does) make a recording these days, but if an artist is not signed Bring a Compass: Part I with a record label, or doesn’t have the resources to make a vanity recording, is there still a way? As Phil Sommerich points out in his excellent overview of “The 8 The Distribution Maze: Distribution Maze,” Part I and Part II, yes, there is a way, or rather, ways. But which Bring a Compass: Part II one is the right one? Sommerich lets us in on a few of the major players, explains 11 Five Minutes, Five Questions how they each work, and the advantages and disadvantages of each. with Three Top Label Execs In “The Musical America Recording Surveys,” we confirmed that our readers are both consumers and makers of recordings. -

The Inspiration Behind Compositions for Clarinetist Frederick Thurston

THE INSPIRATION BEHIND COMPOSITIONS FOR CLARINETIST FREDERICK THURSTON Aileen Marie Razey, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 201 8 APPROVED: Kimberly Cole Luevano, Major Professor Warren Henry, Committee Member John Scott, Committee Member John Holt, Chair of the Division of Instrumental Studies Benjamin Brand, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music John Richmond, Dean of the College of Music Victor Prybutok, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Razey, Aileen Marie. The Inspiration behind Compositions for Clarinetist Frederick Thurston. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), August 2018, 86 pp., references, 51 titles. Frederick Thurston was a prominent British clarinet performer and teacher in the first half of the 20th century. Due to the brevity of his life and the impact of two world wars, Thurston’s legacy is often overlooked among clarinetists in the United States. Thurston’s playing inspired 19 composers to write 22 solo and chamber works for him, none of which he personally commissioned. The purpose of this document is to provide a comprehensive biography of Thurston’s career as clarinet performer and teacher with a complete bibliography of compositions written for him. With biographical knowledge and access to the few extant recordings of Thurston’s playing, clarinetists may gain a fuller understanding of Thurston’s ideal clarinet sound and musical ideas. These resources are necessary in order to recognize the qualities about his playing that inspired composers to write for him and to perform these works with the composers’ inspiration in mind. Despite the vast list of works written for and dedicated to Thurston, clarinet players in the United States are not familiar with many of these works, and available resources do not include a complete listing. -

NMC164 Watkins-Wyas-Booklet

Huw Watkins In my craft or sullen art Mark Padmore tenor Huw Watkins piano Paul Watkins cello Alina Ibragimova violin The Nash Ensemble Elias Quartet Huw Watkins Sonata for Cello and Three Auden Songs 8’47 The Nash Ensemble Eight Instruments 13’44 10 Brussels in Winter 3’31 Artistic Director Amelia Freedman CBE FRAM 1 Allegro 4’36 11 Eyes look into the well 2’51 Paul Watkins cello 2 Lento 5’04 12 At last the secret is out 2’25 Ian Brown conductor 3 Allegro 4’04 Mark Padmore tenor Philippa Davies flute Paul Watkins cello Huw Watkins piano Richard Hosford clarinet The Nash Ensemble Ursula Leveaux bassoon Laura Samuel violin Ian Brown conductor 15’02 Partita for solo violin Catherine Leonard violin 13 Maestoso 4’07 Lawrence Power viola Four Spencer Pieces 15’15 14 Lento ma non troppo 1’06 Duncan McTier double bass 4 Prelude 1’46 15 Lento 4’31 and Huw Watkins piano 5 Shipbuilding on the Clyde 1’49 16 Comodo 1’04 6 The Crucifixion 1’36 17 Allegro molto 4’14 Elias Quartet 7 The Resurrection of Soldiers 5’51 Alina Ibragimova violin Sara Bitlloch violin Separating Fighting Swans 2’28 8 Donald Grant violin 9 Postlude 1’45 18 In my craft or sullen art: Martin Saving viola Marie Bitlloch cello Huw Watkins piano Goodison Quartet No 4 17’31 Mark Padmore tenor Elias Quartet Total timing 71’01 Mark Padmore appears by arrangement with Harmonia Mundi USA. Alina Ibragimova appears on this recording with kind permission from Hyperion Records. -

Bernard Haitink

Sunday 15 October 7–9.05pm Thursday 19 October 7.30–9.35pm Barbican Hall LSO SEASON CONCERT BERNARD HAITINK Thomas Adès Three Studies from Couperin HAITINK Mendelssohn Violin Concerto Interval Brahms Symphony No 2 Bernard Haitink conductor Veronika Eberle violin Sunday 15 October 5.30pm, Barbican Hall LSO Platforms: Guildhall Artists Songs by Mendelssohn and Brahms Guildhall School Musicians Welcome / Kathryn McDowell CBE DL Tonight’s Concert The concert on 15 October is preceded by a n these concerts, Bernard Haitink warmth and pastoral charm (although the performance of songs by Mendelssohn and conducts music that spans the composer joked before the premiere that Brahms from postgraduate students at the eras – the Romantic strains of he had ‘never written anything so sad’), Guildhall School. These recitals, which are Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto; Brahms’ concluding with a joyous burst of energy free to ticket-holders for the LSO concert, Second Symphony; and the sophisticated in the finale. • take place on selected dates throughout Baroque inventions of Couperin, brought the season and provide a platform for the into the present day by Thomas Adès. musicians of the future. François Couperin was one of the most skilled PROGRAMME NOTE WRITERS I hope you enjoy this evening’s performance keyboard composers of his day, and his works and that you will join us again soon. After for harpsichord have influenced composers Paul Griffiths has been a critic for nearly Welcome to the second part of a series of this short series with Bernard Haitink, the through the generations, Thomas Adès 40 years, including for The Times and three LSO concerts, which are conducted by Orchestra returns to the Barbican on 26 among them. -

DMA Option 2 Thesis and Option 3 Scholarly Essay DEPOSIT COVERSHEET University of Illinois Music and Performing Arts Library

DMA Option 2 Thesis and Option 3 Scholarly Essay DEPOSIT COVERSHEET University of Illinois Music and Performing Arts Library Date: DMA Option (circle): 2 [thesis] or 3 [scholarly essay] Your full name: Full title of Thesis or Essay: Keywords (4-8 recommended) Please supply a minimum of 4 keywords. Keywords are broad terms that relate to your thesis and allow readers to find your work through search engines. When choosing keywords consider: composer names, performers, composition names, instruments, era of study (Baroque, Classical, Romantic, etc.), theory, analysis. You can use important words from the title of your paper or abstract, but use additional terms as needed. 1. _________________________________ 2. _________________________________ 3. _________________________________ 4. _________________________________ 5. _________________________________ 6. _________________________________ 7. _________________________________ 8. _________________________________ If you need help constructing your keywords, please contact Dr. Bashford, Director of Graduate Studies. Information about your advisors, department, and your abstract will be taken from the thesis/essay and the departmental coversheet. ÓCopyright 2018 Kyle Shaw PROMISCUITY, FETISHES, AND IRRATIONAL FUNCTIONALITY IN THOMAS ADÈS’S POWDER HER FACE BY KYLE SHAW THESIS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Music with a concentration in Music Composition in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2018 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Reynold Tharp, Chair and Director of Research Assistant Professor Carlos Carrillo Professor Stephen Taylor Professor William Heiles ii ABSTRACT While various scholars have identified Thomas Adès’s primary means of generating pitch material—various patterns of expanding intervals both linear and vertical—there remains a void in the commentary on how his distinct musical voice interacts with the unique demands of articulating a coherent musico-dramatic art form. -

Download Booklet

THE TWENTY-FIFTH HOUR COMPOSER’S NOTE the same musical stuff, as if each were a THE CHAMBER MUSIC OF THOMAS ADÈS (b. 1971) different view through a kaleidoscope. ‘Six of Nearly twenty years separate the two string the seven titles’, he has noted, ‘evoke quartets on this record, and all I have been able various vanished or vanishing “idylls”. The Piano Quintet (2001) * to discover over this time is that music only gets odd-numbered are all aquatic, and would splice 1 I [11.43] more and more mysterious. I am very grateful if played consecutively.’ 2 II [4.35] for this enjoyable collaboration to Signum, Tim 3 III [3.00] Oldham, Steve Long at Floating Earth, and my In the first movement the viola is a gondolier friends the Calder Quartet. poling through the other instruments’ moonlit The Four Quarters (2011) World Premiere Recording 4 I. Nightfalls [7.06] water, with shreds of shadowy waltz drifting 5 II. Serenade: Morning Dew [3.12] Thomas Adès, 2015 in now and then. Next, under a quotation 6 III. Days [3.50] from The Magic Flute (‘That sounds so 7 IV. The Twenty-Fifth Hour [3.51] The Chamber Music delightful, that sounds so divine’ sing of Thomas Adès Monostatos and the slaves when Papageno Arcadiana (1993) plays his bells), comes a song for the cello 8 I. Venezia notturno [2.39] These three works are not only in classic under glistening harmonics. The music is 9 II. Das klinget so herrlich, das klinget so schon [1.22] genres but themselves becoming classics, with stopped twice in its tracks by major chords, 0 III.