Young-Participants-1980-37972-600

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lists of Addresses

LE COMITÉ INTERNATIONAL OLYMPIQUE 23 JUIN 1894 FONDATEUR: M. LE BARON PIERRE DE COUBERTIN 1863-1937 Président d’honneur des Jeux olympiques Commission exécutive : Président : M. Avery Brundage, 10, North La Salle Street, Chicago 2, Illinois. (Cable address : ‘AVAGE’). Vice-présidents : M. Armand Massard, 132, boulevard Suchet, Paris XVIe. The Marquess of Exeter, Burghley House, Stamford (Lincs) England. Membres : M. G.-D. Sondhi, Bamhoo Lodge, Subathu (Simla Hills), Inde. M. Constantin Andrianow, Skatertnyj 4, Moscou. Général José de J. Clark F., Calle de Mil Cumbres 124 ; Lomas Altas de Chapultepec, Mexico. M. Ivar Emil Vind, Sanderumgaard, Fraugde (Danemark). Dr Giorgio de Stefani, 82, Via Savoia, Rome Membre assistant du président : S.E. Mohammed Taher, 40, rue Vermont, Genève. Commissaire aux comptes : Me Marc Hodler, Elfenstrasse 19, Berne. Chancellerie du C. I. O. : Adresse : Mon Repos, Lausanne (Suisse). Télégrammes : CIO, Lausanne. Tél. 22 94 48 Secrétaire général : M. Eric Jonas, Mon-Repos, Lausanne. Secrétaire : Mme L. Zanchi, Mon Repos, Lausanne. Cable address : CIO Lausanne Adresse télégraphique : } MEMBRES HONORAIRES 1923 S. E. Alfredo Benevidès (Pérou), 268, av. Alfredo Benavidès, Miraflores, Lima. 1926 S. A. le Duc Adolphe-Frédéric de Mecklembourg, Schloss Eustin, Holstein, (Allemagne). 1948 Prof. Dr Jerzy Loth, Rakowiecka 6, Varsovie. 1932 Comte Paolo Thaon de Revel, 9, Corso Einaudi, Turin. 1946 Général Pahud de Mortanges, Neptunusflat 7, Scheveningue (Hollande). LISTE, AVEC ADRESSES, DES 71 MEMBRES DU C.I.O. Membre assistant du Président Argentine S.E. MOHAMED TAHER , 40, rue Ver- M. MARIO L. NEGRI , Parana 1273, mont, Genève. Buenos Aires. Australie M. HUGH WEIR , 113, Wallumatta Road, Afrique du Sud New Port, N.S.W. -

Adrian MANNARINO 25E 232E - Lucas POUILLE 11E 131E

DOSSIER DE PRESSE QUART DE FINALE ITALIE VS FRANCE DU 6 AU 8 AVRIL 2018 VALLETTA CAMBIASO ASD GÊNES SHOW YOUR COLOURS MONTIGNY © FFT / P. Infos pratiques LE PROGRAMME PRÉVISIONNEL Vendredi 6 avril 2018 ► A 11h30 : deux premiers simples disputés au meilleur des cinq manches. Samedi 7 avril 2018 ► A 14h00 : double disputé au meilleur des cinq manches. Dimanche 8 avril 2018 ► A 11h30 : deux derniers simples disputés au meilleur des cinq manches *. * Nouveauté 2018, si l’une des deux équipes remporte la rencontre 3-0, le quatrième match sera joué au meilleur des trois sets. Le cinquième match, quant à lui, ne sera pas disputé, sauf si les capitaines et le juge-arbitre en conviennent autrement. Dans ce cas, les deux matches seront joués au meilleur des trois sets avec tie-break dans toutes les manches. LE SITE Adresse : Valletta Cambiaso ASD Via Federico Ricci, 1 Gênes Italie Capacité prévisionnelle : 4 016 places Surface : terre battue extérieure LES BALLES La rencontre sera disputée avec des balles Dunlop Fort Clay Court. LES ARBITRES ► Juge-arbitre : Stefan FRANSSON (SWE) ► Arbitres : James KEOTHAVONG (GBR) et Marijana VELJOVIC (SRB) LES CONFERENCES DE PRESSE DES CAPITAINES* Les capitaines des deux équipes tiendront une conférence de presse le mercredi 4 avril dans la salle de conférence de presse du stade Valletta Cambiaso : - Yannick NOAH : 11h15 - Corrado BARAZZUTTI : 12h00 * IMPORTANT : cette année, seuls les capitaines des deux équipes seront présents lors de la conférence de presse de pré-rencontre. Page | 1 LE PLANNING DES ENTRAÎNEMENTS Les deux équipes se partageront le court du stade Valletta Cambiaso ASD selon la programmation suivante : Mardi 3 avril 09h00 – 12h00 France 12h00 – 15h00 Italie 15h00 – 17h00 France 17h00 – 19h00 Italie Mercredi 4 avril 09h00 – 12h00 Italie 12h00 – 15h00 France 15h00 – 17h00 Italie 17h00 – 19h00 France Les entraînements des jours suivants seront communiqués ultérieurement (après la réunion des capitaines). -

2020 Len European Water Polo Championships

2020 LEN EUROPEAN WATER POLO CHAMPIONSHIPS PAST AND PRESENT RESULTS Cover photo: The Piscines Bernat Picornell, Barcelona was the home of the European Water Polo Championships 2018. Situated high up on Montjuic, it made a picturesque scene by night. This photo was taken at the Opening Ceremony (Photo: Giorgio Scala/Deepbluemedia/Insidefoto) Unless otherwise stated, all photos in this book were taken at the 2018 European Championships in Barcelona 2 BUDAPEST 2020 EUROPEAN WATER POLO CHAMPIONSHIPS PAST AND PRESENT RESULTS The silver, gold and bronze medals (left to right) presented at the 2018 European Championships (Photo: Giorgio Scala/Deepbluemedia/Insidefoto) CONTENTS: European Water Polo Results – Men 1926 – 2018 4 European Water Polo Championships Men’s Leading Scorers 2018 59 European Water Polo Championships Men’s Top Scorers 60 European Water Polo Championships Men’s Medal Table 61 European Water Polo Championships Men’s Referees 63 European Water Polo Club Competitions – Men 69 European Water Polo Results – Women 1985 -2018 72 European Water Polo Championships Women’s Leading Scorers 2018 95 European Water Polo Championships Women’s Top Scorers 96 European Water Polo Championships Women’s Medal Table 97 Most Gold Medals won at European Championships by Individuals 98 European Water Polo Championships Women’s Referees 100 European Water Polo Club Competitions – Women 104 Country By Country- Finishing 106 LEN Europa Cup 109 World Water Polo Championships 112 Olympic Water Polo Results 118 2 3 EUROPEAN WATER POLO RESULTS MEN 1926-2020 -

26. 74Th IOC Session in Varna, 1973. Official Silver Badge

26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 34. 83rd IOC Session in Moscow, 1980. IOC Badge. Bronze, 33x64mm. With white ribbon. EF. ($175) 35. 83rd IOC Session in Moscow, 1980. IOC Commission Badge. Bronze, 33x64mm. With red‑white‑red ribbon. EF. ($150) 36. 83rd IOC Session in Moscow, 1980. National Olympic Committee Badge. Bronze, 33x64mm. With green ribbon. EF. ($150) 37. 83rd IOC Session in Moscow, 1980. NOC Guest Badge. Bronze, 33x64mm. With green‑white‑green ribbon. EF. ($150) 38. 83rd IOC Session in Moscow, 1980. International Federation Badge. Bronze, 33x64mm. Spotty VF‑EF, with light blue ribbon. ($100) 39. 83rd IOC Session in Moscow, 1980. Press Badge. Bronze, 44 45 46 47 48 33x64mm. EF, spot, with dark yellow ribbon. ($150) 26. 74th IOC Session in Varna, 1973. Official Silver Badge. Silvered, 40. 83rd IOC Session Badge in Moscow, 1980. Bronze, 33x64mm. partially enameled, gilt legend, 20x44mm. EF. ($150) With raspberry ribbon. EF. ($150) 27. 77th IOC Session in Innsbruck, 1976. Organizing Committee 41. 11th IOC Congress in Baden-Baden, 1981. IOC Secretariat Badge. Silvered, 35x46mm. With red ribbon, white stripe in center. Badge. Silvered, logo in color, 28x28mm. With white‑red‑white 56 IOC members were present. Lt. wear, abt. EF. Rare. ($575) ribbon. EF. ($200) 28. 22nd Meeting of the IOC and International Federations in 42. 11th IOC Congress in Baden-Baden, 1981. Session Organizing Barcelona, 1976. Television Badge. Gilt, red enamel, 32x50mm. Committee Service Badge. Silvered, logo in color, 27x31mm, with With orange ribbon. EF. -

11 Reglement Honorary Members V2020-Web

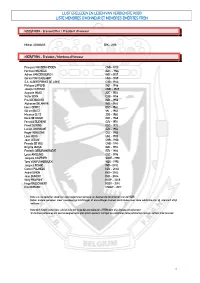

LIJST ERELEDEN EN LEDEN VAN VERDIENSTE KBZB LISTE MEMBRES D’HONNEUR ET MEMBRES ÉMÉRITES FRBN KBZB/FRBN – Erevoorzitter / Président d'Honneur Michel LOUWAGIE BZK - 2018 KBZB/FRBN – Ereleden / Membres d'Honneur François VAN DER HEYDEN CNB - 1928 Herman MACHIELS BZK - 1936 Adrien VAN DEN BURCH IND - 1937 Gérard VAN CAULAERT NSG - 1939 S.A. ALBERT PRINCE DE LIGNE COB - 1944 Philippe LIPPENS IND - 1946 Joseph PLETINCX CNB - 1949 Auguste MAAS AZC - 1953 Victor BOIN COB - 1956 Paul DE BACKER IND - 1956 Alphonse DELAHAYE IND - 1960 Henri OPPITZ BSC - 1961 Gérard BLITZ VN - 1962 Maurice BLITZ ZSB - 1968 René DE RAEVE IND - 1968 Fernand DUCHENE GZV - 1970 Frank SEVENS GSC - 1973 Lucien VANHALME BZK - 1983 Roger VERLOOVE OSC - 1983 Léon HECQ UNL - 1985 Jean LEEUW CNB - 1988 Francis DE VOS CNB - 1990 Brigitte BECUE BZK - 1994 Frederik DEBURGHGRAEVE RZV - 1994 Louis ANTEUNIS GSC - 1996 Jacques CAUFRIER SVDE - 1998 Tony VAN PUYMBROUCK WZK - 1998 Jacques ROGGE IND - 2002 Camiel PAUWELS NZV – 2002 André SIMON IND – 2004 Jean DUMONT IND – 2004 Willy FRAIPONT KVZP – 2008 Hugo RASSCHAERT KGZV – 2010 Paul EVRARD CNHUY – 2017 • Nota van de opsteller: deze lijst werd opgemaakt op basis van bestaande documenten van de KBZB. Indien andere personen meer nauwkeurige inlichtingen of aanvullingen kunnen verstrekken over deze publicatie zijn zij uiteraard altijd welkom. • Note de l’auteur: cette liste a été établie sur base des données de la FRBN dont elle dispose actuellement. Si d’autres personnes ont des renseignements plus précis pouvant corriger ou compléter -

Olympic Culture in Soviet Uzbekistan 1951-1991: International Prestige and Local Heroes

Olympic Culture in Soviet Uzbekistan 1951-1991: International Prestige and Local Heroes Sevket Akyildiz Introduction Uzbekistan was officially established in 1924 by the victorious Bolsheviks as part of a larger union-wide „Soviet people‟ building project. To legitimate and consolidate Moscow‟s rule the southern, largely Muslim, Asian territories (including Uzbekistan) were reorganized under the national delimitation processes of the 1920s and 1930s. Establishing the Soviet republics from the territory formerly known as Turkestan was based upon language, economics, history, culture and ethnicity. Soviet identity building was a dual process fostering state-civic institutions and identity and local national (ethnic) republic identity and interests. The creation of the national republics was part of the Soviet policy of multiculturalism best described a mixed-salad model (and is similar to the British multicultural society model). (Soviet ethnographers termed ethnicity as nationality.) Uzbekistan is situated within Central Asia, a region that the Russians term “Middle Asia and Kazakhstan” – some Western authors also term it “Inner Asia”. Uzbekistan stretches south-east from the Aral Sea towards the Pamir Mountains, and shares borders with Afghanistan (137km), Kazakhstan (2,203km), Kyrgyzstan (1,099km), Tajikistan (1,161km), and Turkmenistan (1,161km). The climate is continental, with hot summers and cold winters. The Uzbeks are a Turkic-speaking people largely Turkic (and Mongol) by descent - and predominately Sunni (Hanafi) Muslim by religious practice. Between 1917 and 1985 the population of Uzbekistan rose from approximately 5 million to 18 million people. However, Uzbekistan was a Soviet multicultural society, and during the Soviet period it contained more than 1.5 million Russian settlers and also included Karakalpaks, Kazakhs, Tajik, Tatars, and several of Stalin‟s deported peoples. -

Doubles Final (Seed)

2016 ATP TOURNAMENT & GRAND SLAM FINALS START DAY TOURNAMENT SINGLES FINAL (SEED) DOUBLES FINAL (SEED) 4-Jan Brisbane International presented by Suncorp (H) Brisbane $404780 4 Milos Raonic d. 2 Roger Federer 6-4 6-4 2 Kontinen-Peers d. WC Duckworth-Guccione 7-6 (4) 6-1 4-Jan Aircel Chennai Open (H) Chennai $425535 1 Stan Wawrinka d. 8 Borna Coric 6-3 7-5 3 Marach-F Martin d. Krajicek-Paire 6-3 7-5 4-Jan Qatar ExxonMobil Open (H) Doha $1189605 1 Novak Djokovic d. 1 Rafael Nadal 6-1 6-2 3 Lopez-Lopez d. 4 Petzschner-Peya 6-4 6-3 11-Jan ASB Classic (H) Auckland $463520 8 Roberto Bautista Agut d. Jack Sock 6-1 1-0 RET Pavic-Venus d. 4 Butorac-Lipsky 7-5 6-4 11-Jan Apia International Sydney (H) Sydney $404780 3 Viktor Troicki d. 4 Grigor Dimitrov 2-6 6-1 7-6 (7) J Murray-Soares d. 4 Bopanna-Mergea 6-3 7-6 (6) 18-Jan Australian Open (H) Melbourne A$19703000 1 Novak Djokovic d. 2 Andy Murray 6-1 7-5 7-6 (3) 7 J Murray-Soares d. Nestor-Stepanek 2-6 6-4 7-5 1-Feb Open Sud de France (IH) Montpellier €463520 1 Richard Gasquet d. 3 Paul-Henri Mathieu 7-5 6-4 2 Pavic-Venus d. WC Zverev-Zverev 7-5 7-6 (4) 1-Feb Ecuador Open Quito (C) Quito $463520 5 Victor Estrella Burgos d. 2 Thomaz Bellucci 4-6 7-6 (5) 6-2 Carreño Busta-Duran d. -

A Conference on Olympic Athletes: Ancient and Modern

1 SCHOOL OF HISTORY, PHILOSOPHY, RELIGION AND CLASSICS A CONFERENCE ON OLYMPIC ATHLETES: ANCIENT AND MODERN 6-8 July 2012 The University of Queensland St Lucia, Brisbane, QLD. 4072 Australia 2 All events associated with the conference are hosted by: The School of History, Philosophy, Religion and Classics Faculty of Arts St Lucia Campus University of Queensland Special thanks go to our sponsors: The School of History, Philosophy, Religion and Classics The Friends of Antiquity, Alumni Friends of the University of Queensland, Inc. The Queensland Friends of the Australian Archaeological Institute at Athens The Australasian Society for Classical Studies Em. Prof. Bob Milns Caillan, Luca, Amelia, Janette and Tom (for the CPDs) and to our volunteers: (R. D. Milns Antiquities Museum) James Donaldson Daniel Press (Committee of Postgraduate Students) Chris Mallan Caitlin Prouatt Julian Barr (Classics and Ancient History Society) Johanna Qualmann Michael Kretowicz Brittany Johansson Jessica Dowdell Lucinda Brabazon Marie Martin Geraldine Porter Caitlin Pudney Kate McKelliget Emily Sievers 3 Table of Contents Page Campus Map and Key Locations 4 Conference Programme 6 Public Lecture Flyer 9 Abstracts 11 Email Contacts 18 Places to Eat at the St Lucia Campus 19 General Information 21 4 CAMPUS MAP AND KEY LOCATIONS 1 = Forgan Smith Building (Conference sessions, Saturday and Sunday) 9 = Michie Building (Welcome Reception, Friday) B = Bus stops/Taxi rank C = CityCat Ferry stop 5 BRISBANE LANDMARKS TOOWONG LANDMARKS 6 School of History, Philosophy, Religion and Classics University of Queensland, Australia A Conference on Olympic Athletes: Ancient and Modern 6-8 July 2012 Website: http://www.uq.edu.au/hprc/olympic-athletes-conference Friday 6 July (2nd floor foyer of Michie / E303 Forgan Smith) 5.30 p.m. -

The Olympic Games in Antiquity the Olympic

THE OLYMPIC GAMES IN ANTIQUITY THE OLYMPIC GAMES INTRODUCTION THE ATHLETE SPORTS ON THE Origins of the modern Olympic Identification of the athlete by PROGRAMME Games, in Olympia, Greece his nakedness, a sign of balance The Olympic programme (Peloponnese), 8th century BC. and harmony as a reference IN ANTIQUITY Gymnasium and palaestra: the Sites of the Panhellenic Games: Foot races, combat sports, education of the body and the mind Olympia, Delphi, Isthmus pentathlon and horse races. of Corinth and Nemea Hygiene and body care. Cheating and fines. History and Mythology: Criteria for participation Music and singing: a particularity explanations of the birth in the Games of the Pythian Games at Delphi. of the Games Exclusion of women Application of the sacred truce: Selection and training peace between cities On the way to Olympia Overview of Olympia, the most Athletes’ and judges’ oath. 6 8 important Panhellenic Games site Other sport competitions in Greece. Winners’ reWARDS THE END OF THE GAMES Prizes awarded at the Panhellenic Over 1,000 years of existence Games Success of the Games Wreaths, ribbons and palm fronds Bringing forward the spirit and the The personification of Victory: values of the Olympic competitions Nike, the winged goddess Period of decline Privileges of the winner upon Abolition of the Games in 393 AD returning home Destruction of Olympia This is a PDF interactive file. The headings of each page contain hyperlinks, Glory and honour which allow to move from chapter to chapter Rediscovery of the site in the Prizes received at local contests 19th century. Superiority of a victory at the Click on this icon to download the image. -

The Biographies of All IOC Members

The Biographies of all IOC Members Part XVII Original manuscript by Ian Buchanan (t) and Wolf Lyberg (t), with additional material by Volker Kluge and Tony Bijkerk 319. | Cornells Lambert KERDELI The Netherlands Born: 19 March 1915. A keen swimmer, he swam each day with the young Dutch women who Rotterdam trained under the legendary "Ma" Braun. At the 1936 Olympic Games in Died: 8 November Berlin, he helped coach Rie Mastenbroek, the outstanding Dutch swimmer 1986, The Hague who won three golds and a silver medal atthose Games. Kerdel was also an enthusiastic skier and was President of the Co-opted: 15 June "Lowlanders" Ski Committee, ar organisation for countries such as Belgium, 1977 (until his death), Denmark, Great Britain and the Netherlands which did not have mountains. replacing Herman In this capacity he became a member of the NOC in i960 and a Vice- van Karnebeek President in 1965, succeeding Herman van Karnebeek as President in 1970. Attendance at He later followed van Karnebeek onto the IOC where he was Head of Protocol Sessions: Presentio, from 1982 until his death. He also served as Chef de Mission of the Dutch Absent 2 Olympic team in i960,196^, 1972 and 1976. A staunch supporter of the European Economic Community, he helped create the Coal Importers' Committee and served as Chairman from 195A to 1965. He died from cancer and was posthumously awarded the Olympic Order. This was presented to his widow by IOC President Juan Antonio Samaranch at a ceremony in Wassenaar on 17thJanuary 1987. 320. | KIM Taik Soo | Republic o f Korea Born: io September A lawyer and a textile magnate, he was an active politician and was elected 1926, Kimhae, three times to the National Assembly. -

Olympic Charter 1956

THE OLYMPIC GAMES CITIUS - ALTIUS - FORTIUS 1956 INTERNATIONAL OLYMPIC COMMITTEE CAMPAGNE MON REPOS LAUSANNE (SWITZERLAND) THE OLYMPIC GAMES FUNDAMENTAL PRINCIPLES RULES AND REGULATIONS GENERAL INFORMATION CITIUS - ALTIUS - FORTIUS PIERRE DE GOUBERTIN WHO REVIVED THE OLYMPIC GAMES President International Olympic Committee 1896-1925. THE IMPORTANT THING IN THE OLYMPIC GAMES IS NOT TO WIN BUT TO TAKE PART, AS THE IMPORTANT THING IN LIFE IS NOT THE TRIUMPH BUT THE STRUGGLE. THE ESSENTIAL THING IS NOT TO HAVE CONQUERED BUT TO HAVE FOUGHT WELL. INDEX Nrs Page I. 1-8 FUNDAMENTAL PRINCIPLES 9 II. HULES AND REGULATIONS OF THE INTERNATIONAL OLYMPIC COMMITTEE 9 Objects and Powers II 10 Membership 11 12 President and Vice-Presidents 12 13 The Executive Board 12 17 Chancellor and Secretary 14 18 Meetings 14 20 Postal Vote 15 21 Subscription and contributions 15 22 Headquarters 15 23 Supreme Authority 15 III. 24-25 NATIONAL OLYMPIC COMMITTEES 16 IV. GENERAL RULES OF THE OLYMPIC GAMES 26 Definition of an Amateur 19 27 Necessary conditions for wearing the colours of a country 19 28 Age limit 19 29 Participation of women 20 30 Program 20 31 Fine Arts 21 32 Demonstrations 21 33 Olympic Winter Games 21 34 Entries 21 35 Number of entries 22 36 Number of Officials 23 37 Technical Delegates 23 38 Officials and Jury 24 39 Final Court of Appeal 24 40 Penalties in case of Fraud 24 41 Prizes 24 42 Roll of Honour 25 43 Explanatory Brochures 25 44 International Sport Federations 25 45 Travelling Expenses 26 46 Housing 26 47 Attaches 26 48 Reserved Seats 27 49 Photographs and Films 28 50 Alteration of Rules and Official text 28 V. -

'Pocket Hercules' – Naim Suleymanoglu

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 4-12-2021 10:00 AM Examining the ‘Pocket Hercules’ – Naim Suleymanoglu: His Life and Career in Olympic Weightlifting and International Sport Oguzhan Keles, The University of Western Ontario Supervisor: Dr. Robert K. Barney, The University of Western Ontario A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the Master of Arts degree in Kinesiology © Oguzhan Keles 2021 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Recommended Citation Keles, Oguzhan, "Examining the ‘Pocket Hercules’ – Naim Suleymanoglu: His Life and Career in Olympic Weightlifting and International Sport" (2021). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 7704. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/7704 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract and Keywords Set within the context under which ethnic-Turks suffered seriously amidst rising communism in post World War II Eastern Europe, this thesis examines the socio- political-cultural circumstances surrounding the life and sporting career of Olympic weightlifter Naim Suleymanoglu, a Bulgarian-born Muslim of Turkish descent. This thesis examines several phases of Suleymanoglu’s life, much of which was devoted to aiding and abetting a mass exodus of Muslim ethnic-Turkish community members from Bulgaria to Turkey, the pursuit of Olympic achievement, and service to the enhancement of the sport of weightlifting in Turkey. By utilizing sports platforms and his remarkable success in weightlifting, widely reported by world media, Suleymanoglu’s life, in the end, translated to a new dimension surrounding the identification of Turkey in the sporting world, one in which weightlifting rivalled time-honoured wrestling as Turkey’s national sport.