Caesar, Succesion, and the Chastisement of Rulers Patrick Martin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SOME NOTES on the FAMILY HISTORY of NICHOLAS LONGFORD, SHERIFF of LANCASHIRE in 1413. the Subject of This Paper Is the Family Hi

47 SOME NOTES ON THE FAMILY HISTORY OF NICHOLAS LONGFORD, SHERIFF OF LANCASHIRE IN 1413. By William Wingfield Longford, D.D., Rector of Sefton. Read March 8, 1934. HE subject of this paper is the family history of T Sir Nicholas Longford of Longford and Withington, in the barony of Manchester, who appears with Sir Ralph Stanley in the roll of the Sheriffs of Lancashire in the year 1413. He was followed in 1414, according to the Hopkinson MSS., by Robert Longford. This may be a misprint for Sir Roger Longford, who was alive in Lan cashire in 1430, but of whom little else is known except that he was of the same family. Sir Nicholas Longford was a knight of the shire for Derbyshire in 1407, fought at Agincourt and died in England in 1416. It might be thought that the appearance of this name in the list of sheriffs on two occasions only, with other names so more frequent and well known from the reign of Edward III onwards Radcliffe, Stanley, Lawrence, de Trafford, Byron, Molyneux, Langton and the rest de.ioted a family of only minor importance, suddenly coming into prominence and then disappearing. But such a con clusion would be ill-founded. The Longford stock was of older standing than any of them, and though the Stanleys rose to greater fame and based their continuance on wider foundations, at the point when Nicholas Long ford comes into the story, the two families were of equal footing and intermarried. Nicholas Longford's daughter Joan was married to John Stanley, son and heir of Sir John Stanley the second of Knowsley. -

The Winter's Tale by William Shakespeare

EDUCATION PACK The Winter’s Tale by William Shakespeare 1 Contents Page Synopsis 3 William Shakespeare 4 Assistant Directing 6 Cue Script Exercise 8 Cue Scripts 9-14 Source of the Story 15 Interview with Simon Scardifield 16 Doubling decisions 17 Propeller 18 2 Synopsis Leontes, the King of Sicilia, asks his dearest friend from childhood, Polixenes, the King of Bohemia, to extend his visit. Polixenes has not been home to his wife and young son for more than nine months but Leontes’ wife, Hermione, who is heavily pregnant, finally convinces her husband's friend to stay a bit longer. As they talk apart, Leontes thinks that he observes Hermione’s behaviour becoming too intimate with his friend, for as soon as they leave his sight he is imagining them "leaning cheek to cheek, meeting noses, kissing with inside lip." He orders one of his courtiers, Camillo, to stand as cupbearer to Polixenes and poison him as soon as he can. Camillo cannot believe that Hermione is unfaithful and informs Polixenes of the plot. He escapes with Polixenes to Bohemia. Leontes, discovering that they have fled, now believes that Camillo knew of the imagined affair and was plotting against him with Polixenes. He accuses Hermione of adultery, takes Mamillius, their son, from her and throws her in jail. He sends Cleomines and Dion to Apollo’s Oracle at Delphi, for an answer to his charges. While Hermione is in jail her daughter is born, and Paulina, her friend, takes the baby girl to Leontes in the hope that the sight of his infant daughter will soften his heart. -

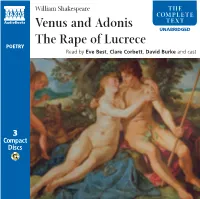

Venus and Adonis the Rape of Lucrece

NA432912 Venus and Adonis Booklet 5-9-6 7/9/06 1:16 pm Page 1 William Shakespeare THE COMPLETE Venus and Adonis TEXT The Rape of Lucrece UNABRIDGED POETRY Read by Eve Best, Clare Corbett, David Burke and cast 3 Compact Discs NA432912 Venus and Adonis Booklet 5-9-6 7/9/06 1:16 pm Page 2 CD 1 Venus and Adonis 1 Even as the sun with purple... 5:07 2 Upon this promise did he raise his chin... 5:19 3 By this the love-sick queen began to sweat... 5:00 4 But lo! from forth a copse that neighbours by... 4:56 5 He sees her coming, and begins to glow... 4:32 6 'I know not love,' quoth he, 'nor will know it...' 4:25 7 The night of sorrow now is turn'd to day... 4:13 8 Now quick desire hath caught the yielding prey... 4:06 9 'Thou hadst been gone,' quoth she, 'sweet boy, ere this...' 5:15 10 'Lie quietly, and hear a little more...' 6:02 11 With this he breaketh from the sweet embrace... 3:25 12 This said, she hasteth to a myrtle grove... 5:27 13 Here overcome, as one full of despair... 4:39 14 As falcon to the lure, away she flies... 6:15 15 She looks upon his lips, and they are pale... 4:46 Total time on CD 1: 73:38 2 NA432912 Venus and Adonis Booklet 5-9-6 7/9/06 1:16 pm Page 3 CD 2 The Rape of Lucrece 1 From the besieged Ardea all in post.. -

The Tragedies: V. 2 Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE TRAGEDIES: V. 2 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK William Shakespeare,Tony Tanner | 770 pages | 07 Oct 1993 | Everyman | 9781857151640 | English | London, United Kingdom The Tragedies: v. 2 PDF Book Many people try to keep them apart, and several lose their lives. Often there are passages or characters that have the job of lightening the mood comic relief , but the overall tone of the piece is quite serious. The scant evidence makes explaining these differences largely conjectural. The play was next published in the First Folio in Distributed Presses. Officer involved with Breonna Taylor shooting says it was 'not a race thing'. Share Flipboard Email. Theater Expert. In tragedy, the focus is on the mind and inner struggle of the protagonist. Ab Urbe Condita c. The 10 Shakespeare plays generally classified as tragedy are as follows:. University of Chicago Press. Retrieved 6 January President Kennedy's sister, Rosemary Kennedy , had part of her brain removed in in a relatively new procedure known as a prefrontal lobotomy. The inclusion of comic scenes is another difference between Aristotle and Shakespearean tragedies. That is exactly what happens in Antony and Cleopatra, so we have something very different from a Greek tragedy. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, , An Aristotelian Tragedy In his Poetics Aristotle outlines tragedy as follows: The protagonist is someone of high estate; a prince or a king. From the minute Bolingbroke comes into power, he destroys the faithful supporters of Richard such as Bushy, Green and the Earl of Wiltshire. Shakespearean Tragedy: Shakespearean tragedy has replaced the chorus with a comic scene. The Roman tragedies— Julius Caesar , Antony and Cleopatra and Coriolanus —are also based on historical figures , but because their source stories were foreign and ancient they are almost always classified as tragedies rather than histories. -

Shakespeare's Rome

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-15906-8 — Shakespeare Survey Edited by Peter Holland Excerpt More Information PAST THE SIZE OF DREAMING? SHAKESPEARE’SROME ROBERT S. MIOLA Ethereal Rumours citizens, its customs, laws and code of honour, its Revive for a moment a broken Coriolanus enemies, wars, histories and myths. But (T. S. Eliot) Shakespeare knew Rome as a modern city of Italy as well, land of love, lust, revenge, intrigue and art, Confronting modernity, the speaker in setting or partial setting for eight plays. Portia dis- ‘ ’ The Wasteland recalled the ancient hero and guises herself as Balthazar, a ‘young doctor of ’ ‘ Shakespeare s play (his most assured artistic suc- Rome’ (Merchant, 4.1.152); Hermione’s statue is ’ cess , Eliot wrote elsewhere) as fragments of past said to be the creation of ‘that rare Italian master, grandeur momentarily shored against his present Giulio Romano’ (The Winter’s Tale, 5.2.96). And ruins. Contrarily, Ralph Fiennes revived Shakespeare knew both ancient and modern fi Coriolanus in his 2011 lm because he thought it Rome as the centre of Roman Catholicism, a modern political thriller: home of the papacy, locus of forbidden devotion For me it has an immediacy: I know that politician and prohibited practice, city of saints, heretics, getting out of that car. I know that combat guy. I’ve martyrs and miracles. The name ‘Romeo’, appro- seen him every day on the news and in the newspaper – priately, identifies a pilgrim to Rome. Margaret that man in that camouflage uniform running down the wishes the college of Cardinals would choose her street, through the smoke and the dust. -

Writing the Shakespeare Mask: the Novelist's Choices

Writing The Shakespeare Mask: The Novelist’s Choices Newton Frohlich *Corresponding Author: [email protected] Copyright©2016 by authors, all rights reserved. Authors agree that this article remains permanently open access under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 International License Abstract The authorship of the works of Shakespeare by de Vere is depicted from when he was five to the time of his the glover from Stratford -on-Avon has been considered a tragic death, including his "favored," sexual relationship myth almost from its inception. No less than Charles Dickins, with the queen and his intimate relationship with Emilia Mark Twain, Henry and William James, Ralph Waldo Bassano, who is widely accepted as the "Dark Lady" of Emerson, Herman Melville, Walt Whitman, Royal Shake-speare's Sonnets. (There is no evidence of any Shakespeare Company actors John Gielgud, Derek Jacobi, relationship between the Stratford man and Emilia Bassano.) Jeremy Irons, and Michael York, British Prime Minister In short, while the documentary evidence of de Vere's -- or Benjamin Disraeli, five United States Supreme Court the Stratford man's -- authorship of the works of Shakespeare Justices, and thousands who signed a Declaration of Doubt is missing, the circumstantial evidence of de Vere's About Will circulating the World-Wide Web have attested to authorship is overwhelming. And as United States Supreme their doubts. In response to the request by his publisher, Court Justice John Paul Stevens puts it, "circumstantial author Newton Frohlich, commencing research connected evidence can be as persuasive as documentary evidence with a sequel to his novel about Columbus, came across especially where, as here, there's so much of it. -

Rape of Lucretia) Tears Harden Lust, Though Marble Wear with Raining./...Herpity-Pleading Eyes Are Sadly Fix’D/In the Remorseless Wrinkles of His Face

ART AND IMAGES IN PSYCHIATRY SECTION EDITOR: JAMES C. HARRIS, MD Tarquin and Lucretia (Rape of Lucretia) Tears harden lust, though marble wear with raining./...Herpity-pleading eyes are sadly fix’d/In the remorseless wrinkles of his face... She conjures him by high almighty Jove/...Byheruntimely tears, her husband’s love,/By holy hu- man law, and common troth,/By heaven and earth and all the power of both,/That to his borrow’d bed he make retire,/And stoop to honor, not to foul desire.1(p17) UCRETIA WAS A LEGENDARY HEROINE OF ANCIENT shadow so his expression is concealed as he rips off Lucretia’s Rome, the quintessence of virtue, the beautiful wife remaining clothing. Lucretia physically resists his violence and of the nobleman Lucius Tarquinius Collatinus.2 brutality. A sculpture decorating the bed has fallen to the floor, In a lull in the war at Ardea in 509 BCE, the young the sheets are in disarray, and Lucretia’s necklace is broken, noblemen passed their idle time together at din- her pearls scattered. Both artists transmit emotion to the viewer, Lners and in drinking bouts. When the subject of their wives came Titian through her facial expression and Tintoretto in the vio- up, every man enthusiastically praised his own, and as their ri- lent corporeal chaos of the rape itself. valry grew, Collatinus proposed that they mount horses and see Lucretia survived the rape but committed suicide. After en- the disposition of the wives for themselves, believing that the best during the rape, she called her husband and her father to her test is what meets his eyes when a woman’s husband enters un- and asked them to seek revenge. -

Galloping Onto the Throne: Queen Elizabeth I and the Symbolism of the Horse

Heidegger 1 Galloping onto the Throne: Queen Elizabeth I and the Symbolism of the Horse University of California, San Diego, Department of History, Undergraduate Honors Thesis By: Hannah von Heidegger Advisor: Ulrike Strasser, Ph.D. April 2019 Heidegger 2 Introduction As she prepared for the impending attack of the Spanish Armada, Queen Elizabeth I of England purportedly proclaimed proudly while on horseback to her troops, “I know I have the body but of a weak and feeble woman; but I have the heart and stomach of a king, and of a king of England too.”1 This line superbly captures the two identities that Elizabeth had to balance as a queen in the early modern period: the limitations imposed by her sex and her position as the leader of England. Viewed through the lens of stereotypical gender expectations in the early modern period, these two roles appear incompatible. Yet, Elizabeth I successfully managed the unique path of a female monarch with no male counterpart. Elizabeth was Queen of England from the 17th of November 1558, when her half-sister Queen Mary passed away, until her own death from sickness on March 24th, 1603, making her one of England’s longest reigning monarchs. She deliberately avoided several marriages, including high-profile unions with Philip II of Spain, King Eric of Sweden, and the Archduke Charles of Austria. Elizabeth’s position in her early years as ruler was uncertain due to several factors: a strong backlash to the rise of female rulers at the time; her cousin Mary Queen of Scots’ Catholic hereditary claim; and her being labeled a bastard by her father, Henry VIII. -

Redating Pericles: a Re-Examination of Shakespeare’S

REDATING PERICLES: A RE-EXAMINATION OF SHAKESPEARE’S PERICLES AS AN ELIZABETHAN PLAY A THESIS IN Theatre Presented to the Faculty of the University of Missouri-Kansas City in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS by Michelle Elaine Stelting University of Missouri Kansas City December 2015 © 2015 MICHELLE ELAINE STELTING ALL RIGHTS RESERVED REDATING PERICLES: A RE-EXAMINATION OF SHAKESPEARE’S PERICLES AS AN ELIZABETHAN PLAY Michelle Elaine Stelting, Candidate for the Master of Arts Degree University of Missouri-Kansas City, 2015 ABSTRACT Pericles's apparent inferiority to Shakespeare’s mature works raises many questions for scholars. Was Shakespeare collaborating with an inferior playwright or playwrights? Did he allow so many corrupt printed versions of his works after 1604 out of indifference? Re-dating Pericles from the Jacobean to the Elizabethan era answers these questions and reveals previously unexamined connections between topical references in Pericles and events and personalities in the court of Elizabeth I: John Dee, Philip Sidney, Edward de Vere, and many others. The tournament impresas, alchemical symbolism of the story, and its lunar and astronomical imagery suggest Pericles was written long before 1608. Finally, Shakespeare’s focus on father-daughter relationships, and the importance of Marina, the daughter, as the heroine of the story, point to Pericles as written for a young girl. This thesis uses topical references, Shakespeare’s anachronisms, Shakespeare’s sources, stylometry and textual analysis, as well as Henslowe’s diary, the Stationers' Register, and other contemporary documentary evidence to determine whether there may have been versions of Pericles circulating before the accepted date of 1608. -

Rape and Resistance of Lavinia in Titus Andronicus

Texture: A Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences 2017 The Body that Writes: Rape and Resistance of Lavinia in Titus Andronicus Arnab Baul Assistant Professor of English Surya Sen College, Siliguri Abstract The violent rape of a woman is at the centre of Shakespeare’s early tragedy ‘Titus Andronicus’. The gang rape of Titus’ daughter Lavinia unsettles our civilized sensibility in terms of its brutality and raises questions regarding rape’s appropriation in socio-cultural space. The play shows, as I argue here, how the violated body of Lavinia has become a site of contestation representing a struggle between Roman patriarchy’s attempted construction of narrative of shame and Lavinia’s courageous rebuttal. Lavinia’s subversion of this strategy of gender stratification by speaking through language of silence and then using writing as performance, shows a rape victim’s regaining of her lost self.The narrative of rape and revenge thus turns into a narrative of resistance when more than the act of violation it is the consequence of violation of the body and the resultant trauma which is highlighted. This paper further shows that an environment that makes it shameful to speak of rape, disallows a critique of rape and the culture that sustains it. I conclude by suggesting that the death of Lavinia, even after registering her protest, bursts forth the state of crafty amnesia of a society which still is befuddled on the issue of appropriating rape both culturally and psychologically. Keywords: Rape, patriarchy, gender-construction, protest, befuddlement And that deep torture may be call’d a hell, When more is felt than one hath power to tell. -

Child Actors, Royalist Publicity, and the Space of the Nation in the Queen’S Men’S True Tragedy of Richard the Third

192 Issues in Review 21 Pietro Aretino, La Talanta, in Giovanna Rabitti, Carmine Boccia, and Enrico Gara- velli (eds), Teatro, Vol. 2 (Il Marescalco, Lo Ipocrito, Talanta) (Roma, 2010): 417 (my translation). 22 Castiglione, The Book of the Courtier, 66. 23 Ibid, 369. 24 For an interesting speculation on the action of Marescalco and the carnivalesque aspect of this ducal manipulation, see Deanna Shemek, ‘Aretino’s Marescalco: Mar- riage Woes and the Duke of Mantua’, Renaissance Studies 16.3 (2002), 366–80. 25 Di Maria, The Italian Tragedy in the Renaissance. Di Maria devotes an interesting and significant discussion to the specific role of sound in the theatre and one work that he examines in detail is Aretino’s tragedy, Orazio. ‘What makes thou upon a stage?’: Child Actors, Royalist Publicity, and the Space of the Nation in the Queen’s Men’s True Tragedy of Richard the Third At the opening of one of their signature histories, The True Tragedy of Richard the Third, the Queen’s Men go out of their way to reassure their audience that what follows will not be a pretentious, inscrutable art play. Yes, a shield- bearing ghost has just crossed the stage crying out for revenge in Senecan Latin,1 and yes, a pair of precocious boys in allegorical women’s clothing now claim our attention.2 Children of some elitist chapel, perhaps? Students from some privileged school? These were tropes that were current not only in London, but also in venues along the Queen’s Men’s provincial touring routes where local nobility patronized choirboys as well as adult compan- ies, and schools taught public speaking through play-making. -

86 Women Under Siege. the Shakespearean Ethics Of

DOI: 10.2478/v10320-012-0030-9 WOMEN UNDER SIEGE. THE SHAKESPEAREAN ETHICS OF VIOLENCE DANA PERCEC and ANDREEA ŞERBAN West University of Timișoara 4, Pârvan Blvd, Timișoara, Romania [email protected] [email protected] Abstract: This paper discusses notions of physical violence, domestic violence, and sexual assault and the ways in which these were socially and legally perceived in early modern Europe. Special attention will be paid to a number of Shakespearean plays, such as Titus Andronicus and Edward III, but also to the narrative poem The Rape of Lucrece (whose motifs were later adopted in Cymbeline), where the consumption of the female body as a work of art is combined with verbal and physical abuse. Key words: consumption, rape, sexual assault, siege, violence Introduction The fourth act of William Shakespeare’s Titus Andronicus opens with the raped and mutilated Lavinia chasing Lucius’ son, gesturing at the book in the boy’s hand, Ovid’s Metamorphoses. She manages to turn the pages to the story of the rape of Philomela, thus informing her father and uncle about Tamora’s sons’ deeds. Starting from this scene, which is one of Ovid’s most prominent influences on Shakespeare’s plays, the paper will discuss notions of physical violence, domestic violence and sexual assault and the way in which they are socially and legally perceived in premodern and early modern Europe. Special attention will be paid to such Shakespearean plays as Titus Andronicus and Edward III, probably the best example of sexual harassment in early modern fiction, but also to the narrative poem The Rape of Lucrece (whose motifs were later adopted in 86 Cymbeline), where the consumption of the female body as a work of art is combined with verbal and physical abuse.