Referring Abroad

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GR01102020 GEMEENTERAADSZITTING VAN 01 OKTOBER 2020 AANWEZIG : Maaike De Rudder, Burgemeester; Herwin De Kind, Harry De Wolf, Wi

GEMEENTERAADSZITTING VAN 01 OKTOBER 2020 AANWEZIG : Maaike De Rudder, burgemeester; Herwin De Kind, Harry De Wolf, Wilbert Dhondt, Erik Rombaut, Marita Meul, schepenen; Greet Van Moer, voorzitter van de gemeenteraad; Remi Audenaert, Chris Lippens, Romain Meersschaert, Tom Ruts, Chantal Vergauwen, Pascal Buytaert, Denis D'hanis, Guido De Lille, Greta Poppe, Koen Daniëls, Matthias Van Zele, Marlene Moorthamers, Dirk Van Raemdonck, Walter Scheerders, Nico De Wert, Iris Ruys - Verbraeken, Marleen Van Hove, Hans Burm, raadsleden; Vicky Van Daele, algemeen directeur VERONTSCHULDIGD: A G E N D A OPENBARE ZITTING Punten college burgemeester en schepenen 1. - Cel Beleidsondersteuning - Veiligheid - Politieverordeningen burgemeester houdende maatregelen ter afremming van corona - bekrachtiging 2. - Burgerzaken en Vrije Tijd - Burgerzaken - Huwelijken op 1 mei 2021 - toelating 3. - Burgerzaken en Vrije Tijd - Cultuur en Toerisme - Goedkeuring rekening 2019 vzw Tempus De Route 4. - Burgerzaken en Vrije Tijd - Cultuur en Toerisme - Budget en jaaractieplan 2020 vzw Tempus De Route - goedkeuring 5. - Cel Beleidsondersteuning - Notulen - Erfpunt - beleidsplan 2021-2026, verlenging Erfpunt, toetreding gemeente Zwijndrecht en uitbreiding werkingsgebied - goedkeuring 6. - Cel Beleidsondersteuning - Cel beleidsondersteuning - Toekenning exclusiviteit aan Interwaas 7. - Welzijn - Wonen en patrimonium - Gemeentelijk reglement op leegstand van gebouwen en woningen - goedkeuring 8. - Welzijn - Wonen en patrimonium - Gemeentelijke belasting op leegstand van gebouwen -

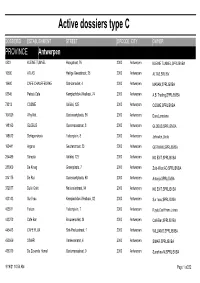

Active Dossiers Type C

Active dossiers type C DOSSIERID ESTABLISHMENT STREET ZIPCODE CITY OWNER PROVINCE Antwerpen 4523 KLEINE TUNNEL Hoogstraat, 76 2000 Antwerpen KLEINE TUNNEL,SPRL/BVBA 16580 ATLAS Heilige Geeststraat, 25 2000 Antwerpen ALTAS,SRL/BV 19680 CAFE CHAUFFEURKE Sint-Jansvliet, 4 2000 Antwerpen MASAN,SPRL/BVBA 63345 Petra's Cafe Kempischdok-Westkaai, 74 2000 Antwerpen A.B. Trading,SPRL/BVBA 73312 COSME Italiëlei, 125 2000 Antwerpen COSME,SPRL/BVBA 104029 Why Not Oudevaartplaats, 56 2000 Antwerpen Dura,Loredana 148160 GLOBUS Oudemansstraat, 8 2000 Antwerpen GLOBUS,SPRL/BVBA 148612 Schippershoek Falconplein, 8 2000 Antwerpen Johnston,Linda 160441 Argana Geuzenstraat, 23 2000 Antwerpen GERWAW,SPRL/BVBA 264489 Sarepta Italiëlei, 123 2000 Antwerpen NO EXIT,SPRL/BVBA 283969 De Kroeg Groenplaats, 7 2000 Antwerpen Zuid-West AD,SPRL/BVBA 314175 De Rui Oudevaartplaats, 60 2000 Antwerpen Antanja,SPRL/BVBA 372877 Dulle Griet Nationalestraat, 94 2000 Antwerpen NO EXIT,SPRL/BVBA 403143 Sur l'eau Kempischdok-Westkaai, 82 2000 Antwerpen Sur l'eau,SPRL/BVBA 405511 Falcon Falconplein, 7 2000 Antwerpen Ruyts,Carl Frans Johan 443272 Café Bar Brouwersvliet, 34 2000 Antwerpen Café Bar,SPRL/BVBA 445413 CAFE FLUX Sint-Paulusstraat, 1 2000 Antwerpen WILLIAMS,SPRL/BVBA 450569 SIMAR Varkensmarkt, 4 2000 Antwerpen SIMAR,SPRL/BVBA 456319 De Zevende Hemel Oudemansstraat, 9 2000 Antwerpen Sunshine-M,SPRL/BVBA 9/16/21 10:54 AM Page 1 of232 DOSSIERID ESTABLISHMENT STREET ZIPCODE CITY OWNER 459399 De Schelde Scheldestraat, 36 2000 Antwerpen SOUTH INVEST,SCS/Comm.V 474854 Antwerp -

113 July 2007

Belgian Laces Queen Elisabeth Musical School Queen Elisabeth, sculpture by Alfred COURTENS Volume 29 - #113 July 2007 Our principal BELGIAN LACES: Official Quarterly Bulletin of objective is: THE BELGIAN RESEARCHERS Keep the Belgian Belgian American Heritage Association Heritage alive ear Members 2007 Queen Elisabeth Competition in our hearts and in DIt had been decades since I had had the wonderful the hearts of our opportunity to listen to the Queen Elisabeth posterity Competition! I was no older than 11 and I listened to the pianists on a small radio I had THE BELGIAN “smuggled” into bed. It’s the year I fell in love RESEARCHERS with Tchaikovsky Piano Concerto and I was in for a treat as many competitors played it. Belgian American This year, although I didn’t have a front row seat, Heritage Association I got to watch the finalists live! on my computer! Our organization was I looked forward to listening to the Belgian founded in 1976 and finalist especially but found myself absolutely taken with the performance of the Russian Anna welcomes as members Vinnitskaya. Even the strange sounds of the The Queen Elisabeth Competition got under way Any person of Belgian compulsory piece seemed to come together in a on May 7th, 2007. No fewer than 75 young descent interested in more pleasant way… What a treat!!! pianists from 26 different countries are taking Genealogy, History, But why am I telling you this and what does it part. Eight Belgians were among those taking to have to do with genealogy and research?! the stage in Brussels' prestigious Royal College of Biography or Heraldry, Well…it doesn’t really, yet it does…Our Music: Lucas Blondeel, Julien Gernay, either amateur or ancestors were more than names and dates and Nikolaas Kende, Milos Popovic, Philippe places… they lived, they felt, they loved, they Raskin, Stéphanie Salmin, Liebrecht professional. -

Viering 150 Jaar Mechelen-Terneuzen

Viering 150 jaar Mechelen-Terneuzen PERSBERICHT, 3 APRIL 2021 Liefhebbers van treinerfgoed zullen zich de komende maanden in het Waasland en Zeeuws-Vlaanderen ten volle kunnen uitleven. Naar aanleiding van de 150ste verjaardag van de spoorlijn Mechelen- Terneuzen ontwikkelt de werkgroep GrensDorpen samen met tal van partners een uitgebreid activiteitenprogramma over de landsgrenzen heen. Het diverse programma past binnen het Europees Jaar van het Spoor en bevat o.a. fiets-en wandelroutes, tentoonstellingen, kunstprojecten en de creatie van een gelegenheidsbier. Historische spoorlijn verbindt Op 10 april 2021 was het precies 150 jaar geleden dat de trein Mechelen-Terneuzen kon doorrijden tot aan de Belgische grens. De eerste trein naar Terneuzen vertrekt op 26 augustus 1871. De werkgroep GrensDorpen, gelinkt aan het KLINGSPOOR aan Wase zijde en aan de Oudheidkundige Kring de Vier Ambachten in Zeeuws-Vlaanderen, probeert over de grens heen samenwerkingen te realiseren. En dat dit succes heeft, blijkt uit dit project. In alle steden en gemeenten langs de lijn Mechelen-Terneuzen komen er initiatieven: in Terneuzen, Hulst, Sint-Gillis-Waas, Sint-Niklaas en Temse springen lokale overheden, verenigingen en regionale organisaties enthousiast mee op de trein. Voor elk wat wils Eén van de blikvangers is een zomerse fietstocht waarbij je heel het parcours kunt affietsen, maar ook lussen kunt maken langs zowel de vroegere ZVTM-lijn in Zeeuws-Vlaanderen als langs het parcours Axel-Moerbeke-Sint-Gillis-Waas om daar weer aan te sluiten op de M-T-lijn. M-T wordt hier spottend “Mèren Trug” genoemd omdat de avondtrein naar Terneuzen bolt terwijl die pas de volgende morgen terugkeert. -

Belgian Laces

Belgian Laces Brugge: The Town Hall created in 1376 is the oldest in Flanders http://www.trabel.com/brugge-m-stadhuis.htm Picture courtesy of the Stedelijke Musea Brugge Volume 21 #80 September 1999 BELGIAN LACES ISSN 1046-0462 Official Quarterly Bulletin of THE BELGIAN RESEARCHERS Belgian American Heritage Association Founded in 1976 Our principal objective is: Keep the Belgian Heritage alive in our hearts and in the hearts of our posterity President Pierre Inghels Vice-President Micheline Gaudette Assistant VP Leen Inghels Newsletter editor Régine Brindle Treasurer Marlena Bellavia Secretary Patty Robinson Deadline for submission of Articles to Belgian Laces: January 25 - April 25 - July 25 - October 25 Send payments and articles to this office: THE BELGIAN RESEARCHERS Régine Brindle 495 East 5th Street Peru IN 46970 Tel:765-473-5667 e-mail [email protected] *All subscriptions are for the calendar year* *New subscribers receive the four issues of the current year, regardless when paid* TABLE OF CONTENTS An Adieu from your President, by Pierre Inghels p49 Letter from the Editor - Membership p49 Interview with Alexander MACAUX, submitted by John MERTENS p50 Declarations of Intention, by MaryAnn DEFNET p51 1860 US Census - Audrain Co., MO, Régine BRINDLE p53 Walloon Forefathers of the Glass Industry, René DOGNEAUX, sent by Lynn D RECKER p54 Belgians found in the 1921 Vincennes, IN Directory, Lynn D RECKER p56 The ROUSSEAU Family, submitted by Raymond POPP p57 War Brides: Simone ANDERSEN, by Simone ANDERSEN p59 1895 US Census - Rice Co., MN, by Lisa McCORMICK p60 Leo BAEKLAND, submitted by Micheline GAUDETTE p63 The Waasland Corner, by Georges PICAVET p64 Concerning the VENESOEN Report, by Hughette DECLERCQ p67 1900 US Census, Cumberland Co. -

Sint-Gillis-Waas 27 W

BODEMKAART VA NB E L G I Ë CARTE DES SOLS DE LA BELGIQUE VERKLARENDE TEKST BIJ HET KAARTBLAD TEXTE EXPLICATIF DE LA PLANCHETTE DE SINT-GILLIS-WAAS 27 W Uitgegeven onder de auspiciën Edité sous les auspices de van het Instituut tot aanmoe• i'Institut pour l'encouragement diging van het Wetenschappe• de la Recherche Scientifique lijk Onderzoek in Nijverheid dans rindiistrie et l'Agricul• en Landbouw (LW.O.N.L.) ture (LR. S. LA.) 1964 Lijst van de bodemkaarten, schaal 1/20 000, met verklarende tekst tc verkrijgen bij het secretariaat van het Comité voor het opnemen van de Bodcmkaart cn de Vegetatiekaart van België, Rozicr 6, Gent mits stordng van dc verkoopprijs op postrekening nr. 3016.86. Bodemkaarten met verklarende tekst in het Nederlands, résumé en français : 1 W Moerkant - 1 E Essen - 2W H orendonii (100 F) 5 E Noordhoek^ - 14 W Kieldrecht - 14 E Ullo (175 F) 6 W Kalmthoutse Hoe\ (100 F) 71 E Aalst 6 E Kalmthout 73 W Vilvoorde 7 W Wuustwezel (100 F) 74 W Haacht 10 W De Haan - 10 E Blankenb. 74 E Rotselaar (lOü F) 75 W Aar schot 11 W Heist 75 E Scherpenheuvel HE West\apeUe-Het Zwin . 76 W Diese (150 F) SO E Proven U E Kapellen 81 W Poperinge 16 W Brecht 81 E leper • 2/ W M{ddel{erf(e - 21 E Oostende 86 E Ninoi'e 22 W Bredene 87 W Asse 22 E Houtave 87 E Andcrlecht , 23 W Brugge 88 W Brussel-Bruxellcs (100 F) 24 W Maldegem 8S E Zavevtem 27 W Sint'Gillis'Waas 89 W Erps^Kwerps 28 E Borgerhout 89 E Leuven 29 W Schilde 90 W Lubbeek 35 W De Panne (100 F) 90 E Glnhheef{'Zuurbemd£ 35 E Oostduini^erlic (100 F) 92 W Znudeeuii/ 36 IV Nieuwpoort -

Een Geschiedenis Van De Wase Klompenmakerij

ERIC DE KEYzer Een geschiedenis van de Wase klompenmakerij Deze studie is een eerbetoon aan de duizenden klompenmakers die in het Waasland groot vakmanschap tentoonspreidden. 1. De oorsprong Waar moeten we beginnen? We zouden in de tijd kunnen teruggaan tot het Egypte van Toetanchamon. Maar worden we daar wijzer van? Toetanchamon is begraven met duizenden attributen voor zijn ondergrondse reis, waaronder een honderdtal schoeisels. De meeste gemaakt van textiel, maar ook enkele van papyrus en zelfs een paar van hout. Zo’n houten paar is ook terugge- vonden in het graf van de Egyptische prinses Henu. Egyptologen als Marleen de Meyer van de KU Leuven bevestigde ons in een persoonlijk contact dat die houten schoeisels enkel ceremoniële toepassingen hadden en niet echt dagelijks werden gedragen. Op houten schoeisel lopen was voor de koningen, farao’s en hogepriesters een voorrecht om bij de goden op bezoek te gaan. Deze houten schoeisels tellen dus niet mee als draagklomp. Wanneer komen klompen op de markt? Wanneer zijn de eerste klompen ver- vaardigd? Zeer waarschijnlijk komt de modale draagklomp in onze streken voor vanaf de 14de eeuw. Een Liber Ordinarius uit de Bibliothèque Nationale in Parijs (Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal nr. 8228) geeft zelfs de 8ste eeuw aan. Even waarschijnlijk ontstonden ze toevallig en werden ze geproduceerd in bijbe- roep, als winteractiviteit. Klompen zijn uit vergankelijk materiaal vervaar- digd, dus veel materiële resten blijven er niet van over. Toch werden zowel in Frankrijk, Nederland als België middeleeuwse ‘trippen’ en ‘hoelblokken’ teruggevonden in de bodem. Waarschijnlijk is de klomp in onze contreien ontstaan vanuit de behoefte aan goedkoop en waterdicht schoeisel tijdens vochtige en killere periodes, waarbij het land overstroomde. -

116 April 2008

Belgian Laces Volume 30 - #116 April 2008 Our principal BELGIAN LACES: Official Quarterly Bulletin of objective is: THE BELGIAN RESEARCHERS Keep the Belgian Belgian American Heritage Association Heritage alive ear Members Bickering Belgians Agree DChuck did it!!! He finished pulling the Belgians on a Deal to Stay One Country in our hearts and in from the WWI Draft Registration Crads!!! Guy just http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp- the hearts of our uploaded New York!!! And Chuck’s not done dyn/content/article/2008/03/18/AR2008031801668.html working! PARIS, March posterity Now he is tackling WWII Drafts cards!!! 18 -- Belgium's Way to go Chuck! THANK YOU SO MUCH!!! feuding political THE BELGIAN Go see the results at parties agreed RESEARCHERS http://www.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~inbr/WWIDraft.htm Tuesday to form a coalition Belgian American In this issue of Belgian Laces you will find an government Heritage Association article that is deceiving in its content in that at the after 9 months Our organization was time I wrote it, it was correct and I had hoped of political chaos founded in 1976 and things would be restored but they have not been that threatened to carve the seat of the and probably won’t be. The method of using the European Union into separate nations. welcomes as members site is still valid however, so I am leaving it as is. "It's a good deal for a government, with Any person of Belgian balanced measures," Yves Leterme, a The information about the Belgian records is still Flemish Christian Democrat who is descent interested in valid and will eventually be accessible through scheduled to become prime minister Genealogy, History, your local Family History Center if the Archives Thursday, told local RTBF radio after an all- persist in not allowing universal access to them. -

Subsidies to the Rescue Introduction

Subsidies to the Rescue The Funding of Poor Relief in Flemish Village Communities during the Cri sis of the 1840s, a Comparative Analysis* Esther Beeckaert tseg 15 (4): 5-32 doi: 10.18352/tseg.1002 Abstract This article questions changes in the funding of local poor relief during the 1845- 1848 food crisis in Flemish village communities. This will be studied comparatively between three distinct regions in Flanders: inner-Flanders, coastal Flanders, and the Waasland. In all three regions it was local relief institutions that increased their finan- cial capacity in order to accommodate rising poverty, despite the long-term advance of nationalized welfare in the background. However, considerable regional differenti- ation could be detected in the nature and degree by which the funding strategies were adapted. This is explained by three interrelated factors: the direct impact of the food crisis, structural economic developments and the political organization of poor relief. Introduction Local relief practices are increasingly stressed in historical debates on the long-term rise of social spending towards the late twentieth cen- tury welfare states.1 As such, the point of departure has considerably been put forward in time, from the late nineteenth century to the pre- * Ghent University (ecc Research group) and Vrije Universiteit Brussel (host Research group). This ar- ticle presents a part of my master thesis Gemeenschap onder druk. Macht en sociale interventie. Sociaal historische en comparatieve microstudie van Vlaamse dorpsgemeenschappen tijdens de crisisjaren 1840, which I wrote in 2016 under the guidance of Eric Vanhaute at Ghent University. 1 On the expansion of poor relief: A. -

Clubblad Nr. 2

Clubblad wandelclub De Smokkelaars Stekene VZW ’t Smokkelaartje 32ste jaargang – nummer 2 1 Bestuur Wandelclub De Smokkelaars Stekene VZW CLUB-INFO: Club-gsm: 0474/74.55.85 ->NL: 0032-474/74.55.85 Voorzitter: Bennie Schuren Vondelstraat 8, Nl-4561LP Hulst 0031-114/31.60.09 [email protected] Algemeen secretariaat: Marleen Van Havermaet Bosdorp 156, B-9190 Stekene 0475/60.86.24 [email protected] Penningmeester: Danny Van der Linden Regentiestraat 38, B-9190 Stekene 03/779.63.59 [email protected] Ledenadministratie + busreizen: Leen de Koning Visartstraat 15, NL-4541BA Sluiskil 0031-115/47.24.55 [email protected] Technisch secretaris: Geert Creve Spoorwegstraat 74, B-2600 Berchem 0486/70.89.02 [email protected] Bestuursleden: Bruno d'Eer (verzending Smokkelaartjes België). Potaarde 53, B-9190 Stekene 03/779.63.79 [email protected] Peter Meyntjens (magazijn). Okkevoordestraat 16, B-9170 Sint-Gillis-Waas 03/707.09.74 [email protected] Anita Colman (kledijwinkel). Huikstraat 33, B-9190 Stekene 03/779.66.10 [email protected] Anne-Marie de Guytenaer (verzending Smokkelaartjes Nederland). Ferdinandstraat 20, NL-4571AP Axel 0031-115/56.38.49 [email protected] Piet Andriessen (Culturele activiteiten+midweektochten) Sint-Sebastiaanstraat 13, 9140 Temse 03/294.95.64 [email protected] 2 27 maart 2018. Kan de sjaal en de muts nu eindelijk opgeborgen worden? Wie had eind januari durven denken dat er in de maanden februari en maart ons toch nog een ouderwetse winter te wachten stond. Ik denk dat weinig mensen hier een weddenschap voor aan hadden willen gaan. Hopelijk kunnen nu de sjaal + muts (een betere 25 deelname-trofee hadden we deze keer niet kunnen kiezen) dan toch eindelijk opgeborgen worden. -

Ir. Herbert Smitz De Ontwikkeling Van De Haven Van Antwerpen De Voorbije 75 Jaar En De Relatie Tot De Scheldepolders Deel 1 Waterbouwkundig Laboratorium 1933-2008 Ir

Ir. Herbert Smitz De ontwikkeling van de haven van Antwerpen de voorbije 75 jaar en de relatie tot de Scheldepolders deel 1 waterbouwkundig laboratorium 1933-2008 Ir. Herbert Smitz De ontwikkeling van de haven van Antwerpen de voorbije 75 jaar en de relatie tot de Scheldepolders deel 1 waterbouwkundig laboratorium 1933-2008 inhoud deel 1 voorwoord 5 1 inleiding 7 2 definities 9 2.1 de Schelde 9 2.2 Polders 9 2.3 waterschappen versus polderbesturen en waterringen 10 3 situering van het scheldebekken en de regio beneden-zeeschelde 13 3.1 voorgeschiedenis van de polders in het huidige havengebied Antwerpen 13 3.2 recente overstromingsrampen in de regio zeeschelde 15 4 de haventechnische ontwikkeling van de haven van Antwerpen op de rechteroever 23 4.1 korte voorgeschiedenis 23 4.2 haventechnische ontwikkeling van de haven van Antwerpen op de Rechterscheldeoever na de wereldoorlog II 25 4.3 het tienjarenplan 1956-1965 26 4.4 na het tienjarenplan: delwaidedok, renovatie en scheldecontainer-terminals 28 5 van de polder(sloten) op de rechteroever tot wereldhaven 35 5.1 de inname van de polder tot haven- en industriegebied rechteroever 35 5.2 oosterweel en oosterweelpolder 37 5.3 de ontwikkeling ten gevolge van het tienjarenplan 37 5.4 bevolkingsevolutie door de havenontwikkeling op de rechteroever 41 5.5 invloed op afwatering van het poldergebied op de rechteroever 46 6 de haventechnische ontwikkeling van de haven van Antwerpen op de linkeroever 57 6.1 de voorbereiding tot de ontwikkeling van de Linkerscheldeoever (1963-68) 57 6.2 industriële -

Infogids 2020 1

Coverfoto: De Loor Hilde INFOGIDS 2020 1 V.U. Gemeente Sint-Gillis-Waas, Maaike De Rudder (burgemeester), Burgemeester Omer De Meyplein 1, 9170 Sint-Gillis-Waas | Omer De Meyplein (burgemeester), 9170 Burgemeester 1, De Rudder Sint-Gillis-Waas Maaike Gemeente Sint-Gillis-Waas, V.U. Sint-Gillis-Waas Colofon Verantwoordelijke uitgever Gemeente Sint-Gillis-Waas, Maaike De Rudder (burgemeester) Burgemeester Omer De Meyplein 1, 9170 Sint-Gillis-Waas Foto’s: voormalige dorpsfotograaf Danny De Saegher / Rudi Wielandt, nieuwe dorpsfotograaf Meer info Communicatie, 03 727 17 00, [email protected] VOLG ONS! www.sint-gillis-waas.be www.facebook.com/gemeentesintgilliswaas Inhoudstafel Voorwoord ...............................................................................................................................................5 Info over onze gemeente ............................................................................................................6 Bestuur en beleid College van burgemeester en schepenen en vast bureau..........................................8-9 Gemeente- en OCMW-raad.....................................................................................................10-13 Bijzonder Comité voor Sociale Dienst......................................................................................13 Gemeentelijke diensten ........................................................................................................16-19 Vrije tijd Sport ........................................................................................................................................................22