A Legacy of Film-Induced Tourism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Under Western Stars by Howard Kazanjian and Chris Enss

Under Western Stars By Howard Kazanjian and Chris Enss King of the Cowboys Roy Rogers made his starring mo- tion picture debut in Republic Studio’s engaging western mu- sical “Under Western Stars.” Released in 1938, the charm- ing, affable Rogers portrayed the most colorful Congressman Congressional candidate Roy Rogers gets tossed into a water trough by his ever to walk up the steps of the horse to the amusement of locals gathered to hear him speak at a political rally. nation’s capital. Rogers’ character, Courtesy Library of Congress Collection. a fearless, two-gun cowboy and ranger from the western town of Sageville, is elected culties with Herbert Yates, head of Republic Studios, to office to try to win legislation favorable to dust bowl paved the way for Rogers to ride into the leading role residents. in “Under Western Stars.” Yates felt he alone was responsible for creating Autry’s success in films and Rogers represents a group of ranchers whose land wanted a portion of the revenue he made from the has dried up when a water company controlling the image he helped create. Yates demanded a percent- only dam decides to keep the coveted liquid from the age of any commercial, product endorsement, mer- hard working cattlemen. Spurred on by his secretary chandising, and personal appearance Autry made. and publicity manager, Frog Millhouse, played by Autry did not believe Yates was entitled to the money Smiley Burnette, Rogers campaigns for office. The he earned outside of the movies made for Republic portly Burnette provides much of the film’s comic re- Studios. -

International Geology Review Unroofing History of Alabama And

This article was downloaded by: [Canadian Research Knowledge Network] On: 2 March 2010 Access details: Access Details: [subscription number 918588849] Publisher Taylor & Francis Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37- 41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK International Geology Review Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t902953900 Unroofing history of Alabama and Poverty Hills basement blocks, Owens Valley, California, from apatite (U-Th)/He thermochronology Guleed A. H. Ali a; Peter W. Reiners a; Mihai N. Ducea a a Department of Geosciences, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, USA To cite this Article Ali, Guleed A. H., Reiners, Peter W. and Ducea, Mihai N.(2009) 'Unroofing history of Alabama and Poverty Hills basement blocks, Owens Valley, California, from apatite (U-Th)/He thermochronology', International Geology Review, 51: 9, 1034 — 1050 To link to this Article: DOI: 10.1080/00206810902965270 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00206810902965270 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. -

Board of Supervisors

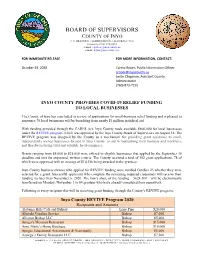

BOARD OF SUPERVISORS COUNTY OF INYO P. O. DRAWER N INDEPENDENCE, CALIFORNIA 93526 TELEPHONE (760) 878-0373 e-mail: [email protected] e-mail: [email protected] FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE FOR MORE INFORMATION, CONTACT: October 29, 2020 Carma Roper, Public Information Officer [email protected] Leslie Chapman, Assistant County Administrator (760) 873-7191 INYO COUNTY PROVIDES COVID-19 RELIEF FUNDING TO LOCAL BUSINESSES The County of Inyo has concluded its review of applications for small-business relief funding and is pleased to announce 78 local businesses will be benefiting from nearly $1 million in federal aid. With funding provided through the CARES Act, Inyo County made available $800,000 for local businesses under the REVIVE program, which was approved by the Inyo County Board of Supervisors on August 18. The REVIVE program was designed by the County as a mechanism for providing grant assistance to small, independently owned businesses located in Inyo County, to aid in maintaining their business and workforce and thereby restoring vital and valuable local commerce. Grants ranging from $5,000 to $25,000 were offered to eligible businesses that applied by the September 18 deadline and met the expressed, written criteria. The County received a total of 102 grant applications, 78 of which were approved with an average of $10,256 being awarded to the grantees. Inyo County business owners who applied for REVIVE funding were notified October 23 whether they were selected for a grant. Successful applicants who complete the remaining required credentials will receive their funding no later than November 6, 2020. The lion’s share of the funding – $624,300 – will be electronically transferred on Monday, November 1 to 64 grantees who have already completed their paperwork. -

Department of Management Working Paper Series I S S N 1 3 2 7 – 5 2 1 6

CREATING AN IMAGE: FILM-INDUCED FESTIVALS IN THE AMERICAN WEST Warwick Frost Working Paper 34/06 October 2006 DEPARTMENT OF MANAGEMENT WORKING PAPER SERIES I S S N 1 3 2 7 – 5 2 1 6 Abstract Film and television are major forces in shaping destination image and encouraging tourism visitation. A growing literature reports on how film and television either directly attract tourists or is incorporated into destination marketing campaigns. However, there has been little research examining how film and television may be used in festivals and events and how destinations may actively use such festivals as a medium for creating their destination image. This article considers film-induced festivals in the small American towns of Lone Pine and Jamestown. Both have been extensively used as film locations since the 1920s, primarily for Westerns. Lone Pine has been the location for over 350 films, and Jamestown has been the location for 150 films. Through film-themed festivals, these towns have reshaped their destination images as idealised and romanticised Western locales. In contrast other aspects of their heritage have been downplayed causing some dissonance between stakeholders. This paper is a work in progress. Material in the paper cannot be used without permission of the author. 2 CREATING AN IMAGE: FILM-INDUCED FESTIVALS IN THE AMERICAN WEST INTRODUCTION In Film-induced tourism (2005), Sue Beeton examines how destinations utilise feature films and television to attract tourists. Many destinations incorporate film into their marketing, some develop film-based attractions, but Beeton only records one that has developed a festival based on its film image. -

Feature Films

Libraries FEATURE FILMS The Media and Reserve Library, located in the lower level of the west wing, has over 9,000 videotapes, DVDs and audiobooks covering a multitude of subjects. For more information on these titles, consult the Libraries' online catalog. 0.5mm DVD-8746 2012 DVD-4759 10 Things I Hate About You DVD-0812 21 Grams DVD-8358 1000 Eyes of Dr. Mabuse DVD-0048 21 Up South Africa DVD-3691 10th Victim DVD-5591 24 Hour Party People DVD-8359 12 DVD-1200 24 Season 1 (Discs 1-3) DVD-2780 Discs 12 and Holding DVD-5110 25th Hour DVD-2291 12 Angry Men DVD-0850 25th Hour c.2 DVD-2291 c.2 12 Monkeys DVD-8358 25th Hour c.3 DVD-2291 c.3 DVD-3375 27 Dresses DVD-8204 12 Years a Slave DVD-7691 28 Days Later DVD-4333 13 Going on 30 DVD-8704 28 Days Later c.2 DVD-4333 c.2 1776 DVD-0397 28 Days Later c.3 DVD-4333 c.3 1900 DVD-4443 28 Weeks Later c.2 DVD-4805 c.2 1984 (Hurt) DVD-6795 3 Days of the Condor DVD-8360 DVD-4640 3 Women DVD-4850 1984 (O'Brien) DVD-6971 3 Worlds of Gulliver DVD-4239 2 Autumns, 3 Summers DVD-7930 3:10 to Yuma DVD-4340 2 or 3 Things I Know About Her DVD-6091 30 Days of Night DVD-4812 20 Million Miles to Earth DVD-3608 300 DVD-9078 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea DVD-8356 DVD-6064 2001: A Space Odyssey DVD-8357 300: Rise of the Empire DVD-9092 DVD-0260 35 Shots of Rum DVD-4729 2010: The Year We Make Contact DVD-3418 36th Chamber of Shaolin DVD-9181 1/25/2018 39 Steps DVD-0337 About Last Night DVD-0928 39 Steps c.2 DVD-0337 c.2 Abraham (Bible Collection) DVD-0602 4 Films by Virgil Wildrich DVD-8361 Absence of Malice DVD-8243 -

Movie History in Lone Pine, CA

Earl’s Diary - Saturday - February 1, 2014 Dear Loyal Readers from near and far; !Boy, was it cold last night! When I looked out the window this morning, the sun was shining and the wind still blowing. As I looked to the west, I found the reason for the cold. The wind was blowing right off the mountains covered with snow! The furnace in The Peanut felt mighty good! !Today was another sightseeing day. My travels took me to two sites in and around Lone Pine. The two sites are interconnected by subject matter. You are once again invited to join me as I travel in Lone Pine, California. !My first stop was at the Movie History Museum where I spent a couple hours enjoying the history of western movies - especially those filmed here in Lone Pine. I hurried through the place taking pictures. There were so many things to see that I went back after the photo taking to just enjoy looking and reading all the memorabilia. This was right up my alley. I spent my childhood watching cowboys and Indians, in old films showing on afternoon TV and in original TV shows from the early 50's on. My other interest is silent movies. This museum even covers that subject. ! This interesting place has an impressively large collection of movie props from all ages of film. They've got banners and posters from the 20's, sequined cowboy jumpers and instruments used by the singing cowboys of the 30's and 40's, even the guns and costumes worn by John Wayne, Clint Eastwood and several other iconic cowboy actors. -

MGM 70 YEARS: REDISCOVERIES and CLASSICS June 24 - September 30, 1994

The Museum of Modern Art For Immediate Release May 1994 MGM 70 YEARS: REDISCOVERIES AND CLASSICS June 24 - September 30, 1994 A retrospective celebrating the seventieth anniversary of Metro-Goldwyn- Mayer, the legendary Hollywood studio that defined screen glamour and elegance for the world, opens at The Museum of Modern Art on June 24, 1994. MGM 70 YEARS: REDISCOVERIES AND CLASSICS comprises 112 feature films produced by MGM from the 1920s to the present, including musicals, thrillers, comedies, and melodramas. On view through September 30, the exhibition highlights a number of classics, as well as lesser-known films by directors who deserve wider recognition. MGM's films are distinguished by a high artistic level, with a consistent polish and technical virtuosity unseen anywhere, and by a roster of the most famous stars in the world -- Joan Crawford, Clark Gable, Judy Garland, Greta Garbo, and Spencer Tracy. MGM also had under contract some of Hollywood's most talented directors, including Clarence Brown, George Cukor, Vincente Minnelli, and King Vidor, as well as outstanding cinematographers, production designers, costume designers, and editors. Exhibition highlights include Erich von Stroheim's Greed (1925), Victor Fleming's Gone Hith the Hind and The Wizard of Oz (both 1939), Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), and Ridley Scott's Thelma & Louise (1991). Less familiar titles are Monta Bell's Pretty Ladies and Lights of Old Broadway (both 1925), Rex Ingram's The Garden of Allah (1927) and The Prisoner - more - 11 West 53 Street, New York, N.Y. 10019-5498 Tel: 212-708-9400 Cable: MODERNART Telex: 62370 MODART 2 of Zenda (1929), Fred Zinnemann's Eyes in the Night (1942) and Act of Violence (1949), and Anthony Mann's Border Incident (1949) and The Naked Spur (1953). -

Alabama Hills Management Plan Comments

Steve Nelson, Field Manager Sherri Lisius, Assistant Field Manager Bureau of Land Management 351 Pacu Lane, Suite 100 Bishop, CA 93514 Submitted via email: [email protected] RE: DOI-BLM-CA-C070-2020-0001-EA Bishop BLM Field Office and Alabama Hills Planning Team, Thank you for the opportunity to review and submit comments on the DOI-BLM-CA-C070-2020-0001-EA for the Alabama Hills Draft Management Plan, published July 8th 2020. Please accept these comments on behalf of Friends of the Inyo and our 1,000+ members across the state of California and country. About Friends of the Inyo & Project Background Friends of the Inyo is a conservation non-profit 501(c)(3) based in Bishop, California. We promote the conservation of public lands ranging from the eastern slopes of Yosemite to the sands of Death Valley National Park. Founded in 1986, Friends of the Inyo has over 1,000 members and executes a variety of conservation programs ranging from interpretive hikes, trail restoration, exploratory outings, and public lands policy engagement. Over our 30-year history, FOI has become an active partner with federal land management agencies in the Eastern Sierra and California Desert, including extensive work with the Bishop BLM. Friends of the Inyo was an integral partner in gaining the passage of S.47, or the John D. Dingell Jr. Conservation, Management, and Recreation Act, that designated the Alabama Hills as a National Scenic Area. Our board and staff have served this area for many years and have seen it change over time. With this designation comes the opportunity to address these changes and promote the conservation of the Alabama Hills. -

Alabama Hills Management Plan 351 Pacu Lane, Suite 100 Bishop, CA 93514

December 23, 2019 BLM Bishop Field Office Attn: Alabama Hills Management Plan 351 Pacu Lane, Suite 100 Bishop, CA 93514 Submitted Via Email to [email protected]: RE: Access Fund Comments on Alabama Hills Management Plan Scoping Process Dear BLM Bishop Field Office Planning Staff, The Access Fund and Outdoor Alliance California (OACA) appreciate this opportunity to provide preliminary comments on the BLM’s initial scoping process for the Alabama Hills National Scenic Area (NSA) and National Recreation Area (NRA) Management Plan. The Alabama Hills provide a unique and valuable climbing and recreational experience within day trip distance of several major population centers. The distinct history, rich cultural resources, dramatic landscape, and climbing opportunities offered by the Alabama Hills have attracted increasing numbers of visitors, something which the new National Scenic Area designation1 will compound, leading to a need for proactive management strategies to mitigate growing impacts from recreation. We look forward to collaborating with the BLM on management strategies that protect both the integrity of the land and continued climbing opportunities. The Access Fund The Access Fund is a national advocacy organization whose mission keeps climbing areas open and conserves the climbing environment. A 501c(3) nonprofit and accredited land trust representing millions of climbers nationwide in all forms of climbing—rock climbing, ice climbing, mountaineering, and bouldering—the Access Fund is a US climbing advocacy organization with over 20,000 members and over 123 local affiliates. Access Fund provides climbing management expertise, stewardship, project specific funding, and educational outreach. California is one of Access Fund’s largest member states and many of our members climb regularly at the Alabama Hills. -

Geologic Map of the Lone Pine 15' Quadrangle, Inyo County, California

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR GEOLOGIC INVESTIGATIONS SERIES U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY MAP I–2617 118°15' 118°10' 118°5' 118°00' ° 36°45' 36 45' CORRELATION OF MAP UNITS Alabama Hills Early Cretaceous age. In northern Alabama Hills, dikes and irregular hy- SW1/4NE1/4 sec. 19, T. 15 S., R. 37 E., about 500 m east of the boundary with the Lone tures that define the fault zone experienced movement or were initiated at the time of the Kah Alabama Hills Granite (Late Cretaceous)—Hypidiomorphic seriate to pabyssal intrusions constitute more than 50 percent, and locally as much Pine 15' quadrangle. Modal analyses of 15 samples determined from stained-slab and 1872 earthquake. SURFICIAL DEPOSITS d faintly porphyritic, medium-grained biotite monzogranite that locally as 90 percent, of the total rock volume over a large area (indicated by thin-section point counts indicate that the unit is composed of monzogranite (fig. 4). Ad- Most traces of the Owens Valley Fault Zone in the quadrangle cut inactive alluvium contains equant, pale-pink phenocrysts of potassium feldspar as large as pattern). Some of these dikes may be genetically associated with the ditional description and interpretation of this unusual pluton are provided by Griffis (Qai) and older lake deposits (Qlo). Some scarps, however, cut active alluvial deposits Qa 1 cm. Outcrop color very pale orange to pinkish gray. Stipple indicates lower part of the volcanic complex of the Alabama Hills (Javl) (1986, 1987). (Qa) that fringe the Alabama Hills north of Lone Pine, and the most southeasterly trace of Qly Qs local fine-grained, hypabyssal(?) facies. -

To Be Yellow, Brave, and Disappeared in Bad Day at Black Rock

New Voices Conference "Patriotic Drunk": To be Yellow, Brave, and Disappeared in Bad Day at Black Rock John Streamas John Sturges' 1954 Hollywood feature film Bad Day at Black Rock is a brave indictment of two kinds of intolerance: racism and McCarthyism. Its racial narrative is unusual. While most Hollywood denunciations of racism construct sympathetic victims who are liberated into freedom and autonomy by a white hero, as in Snow Falling on Cedars, Sturges' film shows no one being racially oppressed, much less liberated. To be sure, a Japanese American farmer in the remote Southwestern desert town of Black Rock is murdered soon after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, but this happens four years before the film's "bad day" and is thus never shown. All the characters are white, and the protagonist Macreedy is an unlikely champion of racial justice, a luckless veteran so badly injured in combat that he has lost the use of an arm. The absence of Japanese Americans in Bad Day at Black Rock acknowledges the historical reality of a policy by which a central government removed and relocated a subject racial community. An absence in a space from which people have been removed can go unnoticed—which is of course what the oppressor wants—or it can be recognized as a site of oppression and thus can provoke political and cultural action. I argue here that Sturges' film, which I approach through Rea Tajiri's 1991 documentary film History and Memory, achieves at least a rare recognition of injustice.1 0026-3079/2003/4401-099S2.50/0 American Studies, 44:1-2 (Spring/Summer 2003): 99-119 99 100 John Streamas History and Memory is an experimental film, a quilted reconstruction of Tajiri's mother's memory of wartime relocation and her own construction of the war, set against the dominant narrative of relocation and incarceration. -

Nothing Happened

NOTHING HAPPENED A History Susan A. Crane !"#$%&'( )$*+,'-*". /',-- Stanford, California !"#$%&'( )$*+,'-*". /',-- Stanford, California ©2020 by the Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior University. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system without the prior written permission of Stanford University Press. Printed in the United States of America on acid-free, archival-quality paper Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Crane, Susan A., author. Title: Nothing happened : a history / Susan A. Crane. Description: Stanford, California : Stanford University Press, [2020] | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2020013808 (print) | LCCN 2020013809 (ebook) | ISBN 9781503613478 (cloth) | ISBN 9781503614055 (epub) Subjects: LCSH: History—Philosophy. | Collective memory. Classification: LCC D16.9 .C73 2020 (print) | LCC D16.9 (ebook) | DDC 901—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020013808 LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020013809 Cover design: Rob Ehle Cover photos: Historical marker altered from photo (Brian Stansbury) of a plaque commemorating the Trail of Tears, Monteagle, TN, superimposed on photo of a country road (Paul Berzinn). Both via Wikimedia Commons. Text design: Kevin Barrett Kane Typeset at Stanford University Press in 11/15 Mercury Text G1 A mind lively and at ease can do with seeing nothing, and can see nothing that does not answer. J#$, A0-",$, E MMA CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Episodes in a History of Nothing 1 EPISODE 1 Studying How Nothing Happens 21 EPISODE 2 Nothing Is the Way It Was 67 EPISODE 3 Nothing Happened 143 CONCLUSION There Is Nothing Left to Say 217 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Thanks for Nothing 223 Notes! 227 Index 239 NOTHING HAPPENED Introduction EPISODES IN A HISTORY OF NOTHING !"#$# %&'()"**# +'( ,#**-.