Growth Potential Study 2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shore Angling Ladies (Langebaan)

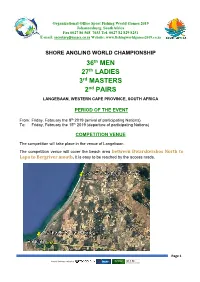

Organizational Office Sport Fishing World Games 2019 Johannesburg, SouthAfrica Fax 0027 86 568 7653 Tel. 0027 82 829 8251 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.fishingworldgames2019.co.za SHORE ANGLING WORLD CHAMPIONSHIP 36th MEN 27th LADIES 3rd MASTERS 2nd PAIRS LANGEBAAN, WESTERN CAPE PROVINCE, SOUTH AFRICA PERIOD OF THE EVENT From: Friday, February the 8th 2019 (arrival of participating Nations) To: Friday, February the 15th 2019 (departure of participating Nations) COMPETITION VENUE The competition will take place in the venue of Langebaan. The competition venue will cover the beach area between Dwarskersbos North to Lapa to Bergriver mouth. It is easy to be reached by the access roads. Page 1 Event Partners includes: Organizational Office Sport Fishing World Games 2019 Johannesburg, SouthAfrica Fax 0027 86 568 7653 Tel. 0027 82 829 8251 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.fishingworldgames2019.co.za Welcome by the President of the South African Shore Angling Association Dear angling friends, It is with great pleasure that we invite, on behalf of the South African Shore Angling Association, your national Federation to participate in the 2019 Shore Angling World Championships We are honored to partner with SASACC and that C.I.P.S. and FIPS-M have granted South Africa, and the village of Langebaan the opportunity and trust to host the world`s best sport sea anglers. We glad fully accept the challenge to present the most memorable tournament your Federation / Association will have ever experienced as our angling is the best in the world. South Africa is the Rainbow nation of the world due to our various cultures and we invite you to share our hospitality and natural beauty. -

A Revision of the 2004 Growth Potential of Towns in the Western Cape Study

A revision of the 2004 Growth Potential of Towns in the Western Cape study Discussion document A research study undertaken for the Department of Environmental Affairs and Development Planning of the Western Cape Provincial Government by Stellenbosch University & CSIR RESEARCH TEAM Dr Adriaan van Niekerk* (Project Manager) Prof Ronnie Donaldson* Mr Danie du Plessis† Mr Manfred Spocter‡ We are thankful to the following persons for their assistance: Ms I Boonzaaier*, Mr Nitesh Poona*, Ms T Smith*, Ms Lodene Willemse* * Centre for Geographical Analysis (CGA), Stellenbosch University † Centre for Regional and Urban Innovation and Statistical Exploration (CRUISE), Stellenbosch University ‡ Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) 17 January 2010 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za ii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY One of the objectives of the Department of Environmental Affairs and Development Planning (DEA&DP) is to undertake spatial planning that promotes and guides the sustainable future development of the Western Cape province and redresses spatial inequalities. This goal led to the development of the Provincial Spatial Development Framework (PSDF), which identifies the areas of growth in the province and the areas where, in terms of the sustainable development paradigm, growth should be emphasised in the future. It also addresses the form that this growth or development should take and further emphasises the restructuring of urban settlements to facilitate their sustainability. To provide guidance and support for implementing the PSDF, a thorough understanding and knowledge of the characteristics and performances of all the settlements in the province is needed. The aim of this study was to revise and update the Growth Potential Study of Towns in the Western Cape (Van der Merwe et al. -

Swartland Municipality Integrated Development Plan for 2017-2022

Swartland Municipality Integrated Development Plan for 2017-2022 THIRD AMENDMENT 28 MAY 2020 INTEGRATED DEVELOPMENT PLAN FOR 2017-2022 Compiled in terms of the Local Government: Municipal Systems Act, 2000 (Act 32 of 2000) Amendments approved by the Municipal Council on 28 May 2020 The Integrated Development Plan is the Municipality’s principal five year strategic plan that deals with the most critical development needs of the municipal area (external focus) as well as the most critical governance needs of the organisation (internal focus). The Integrated Development Plan – is adopted by the council within one year after a municipal election and remains in force for the council’s elected term (a period of five years); is drafted and reviewed annually in consultation with the local community as well as interested organs of state and other role players; guides and informs all planning and development, and all decisions with regard to planning, management and development; forms the framework and basis for the municipality’s medium term expenditure framework, annual budgets and performance management system; and seeks to promote integration by balancing the economic, ecological and social pillars of sustainability without compromising the institutional capacity required in the implementation, and by coordinating actions across sectors and spheres of government. AREA PLANS FOR 2020/2021 The five area plans, i.e. Swartland North (Moorreesburg and Koringberg), Swartland East (Riebeek West and Riebeek Kasteel), Swartland West (Darling and Yzerfontein), Swartland South (Abbotsdale, Chatsworth, Riverlands and Kalbaskraal) and Swartland Central (Malmesbury) help to ensure that the IDP is more targeted and relevant to addressing the priorities of all groups, including the most vulnerable. -

Growth Potential of Towns in the Western Cape

Growth Potential of Towns in the Western Cape WESTERN CAPE SPATIAL INFORMATION FORUM 14 November 2013 Growth Potential Study (GPS) of Towns IN A NUTSHELL PURPOSE? Purpose of the GPS is not to identify where growth (e.g. economic, population and physical) should occur, but rather where it is likely to occur (in the absence of significant interventions). HOW? Use quantitative data (measurements) to model the growth preconditions and innovation potential. BACKGROUND • 2004: GPS1 • Van der Merwe, Zietsman, Ferreira, Davids • 2010: GPS2 • Van Niekerk, Donaldson, Du Plessis, Spocter • 2012/13: GPS3 • Van Niekerk, Donaldson, Du Plessis, Spocter, Ferreira, Loots GPS3: PROJECT PLAN 1. Functional region mapping 2. Qualitative analysis 3. Public participation 4. Public sector priorities alignment 5. Quantitative analysis 6. Draft Report 7. Public comment GPS3: PROJECT PLAN 1. Functional region mapping 2. Qualitative analysis 3. Public participation 4. Public sector priorities alignment 5. Quantitative analysis 6. Draft Report 7. Public comment QUANTITATIVE ANALYSIS QUANTITATIVE ANALYSIS PROCEDURE 1. Create conceptual framework for estimating growth potential 2. Identify indicators that address growth potential concepts 3. Collect and manipulate data 4. Carry out statistical analyses to reduce data duplication 5. Carry out spatial analyses 6. Perform sensitivity analysis 7. Present and interpret the results DATA COLLECTION & MANIPULATION • Needed to collect data for all local municipalities and 131 settlements (as defined in GPS1) • Thiessen (Voronoi) -

Overstrand Municipality

OVERSTRAND MUNICIPALITY INTEGRATED WASTE MANAGEMENT PLAN (4th Generation) (Final Report) Compiled by: Jan Palm Consulting Engineers Specialist Waste Management Consultants P O Box 931 BRACKENFELL, 7561 Tel: (021) 982 6570 Fax: (021) 981 0868 E-mail: [email protected] MAY 2015 -i- OVERSTRAND MUNICIPALITY INTEGRATED WASTE MANAGEMENT PLAN INDEX EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................................................ 1 INTRODUCTION AND GENERAL DESCRIPTION ............................................................................................... 1 1. PREFACE ............................................................................................................................................ 13 1.1 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................. 13 1.2 IWMP DEVELOPMENT ........................................................................................................................ 14 1.3 OVERSTRAND MUNICIPALITY GENERAL DESCRIPTION ............................................................... 14 1.3.1 GEOLOGY AND HYDROGEOLOGY ................................................................................................... 16 1.3.2 HYDROLOGY ...................................................................................................................................... 17 1.4 DEMOGRAPHICS ............................................................................................................................... -

Freshwater Fishes

WESTERN CAPE PROVINCE state oF BIODIVERSITY 2007 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter 1 Introduction 2 Chapter 2 Methods 17 Chapter 3 Freshwater fishes 18 Chapter 4 Amphibians 36 Chapter 5 Reptiles 55 Chapter 6 Mammals 75 Chapter 7 Avifauna 89 Chapter 8 Flora & Vegetation 112 Chapter 9 Land and Protected Areas 139 Chapter 10 Status of River Health 159 Cover page photographs by Andrew Turner (CapeNature), Roger Bills (SAIAB) & Wicus Leeuwner. ISBN 978-0-620-39289-1 SCIENTIFIC SERVICES 2 Western Cape Province State of Biodiversity 2007 CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION Andrew Turner [email protected] 1 “We live at a historic moment, a time in which the world’s biological diversity is being rapidly destroyed. The present geological period has more species than any other, yet the current rate of extinction of species is greater now than at any time in the past. Ecosystems and communities are being degraded and destroyed, and species are being driven to extinction. The species that persist are losing genetic variation as the number of individuals in populations shrinks, unique populations and subspecies are destroyed, and remaining populations become increasingly isolated from one another. The cause of this loss of biological diversity at all levels is the range of human activity that alters and destroys natural habitats to suit human needs.” (Primack, 2002). CapeNature launched its State of Biodiversity Programme (SoBP) to assess and monitor the state of biodiversity in the Western Cape in 1999. This programme delivered its first report in 2002 and these reports are updated every five years. The current report (2007) reports on the changes to the state of vertebrate biodiversity and land under conservation usage. -

Call to Join the Verlorenvlei Coalition

TUNGSTEN MINE THREATENS WAY OF LIFE OF THOUSANDS AND PLACES RAMSAR-SITE VERLORENVLEI AT HIGH RISK · We the people of the Verlorenvallei stand as one against a threat which could destroy our way of life and our valley. · We the farm workers, fishermen, farmers and entrepreneurs will not allow the pollution of our air, water or land or loss of our livelihoods for the sake of a greedy few. · We the lovers of nature reject further desecration of the already endangered Verlorenvlei and the unique and wide variety of animals, birds, reptiles and plants which have survived the depredations of humans. · We will protect the rare and largely unexplored rich pre-historical heritage for those who may follow us. · We have formed the Verlorenvlei Coalition; we are growing steadily, please join. The Verlorenvlei Coalition (VC) is a coalition of labour, business, civic organisations, environmental groups and local residents formed to preserve the integrity of the area and its people. We call our valley, which runs from Piketberg to Elands Bay, the Verlorenvallei. THE CHALLENGE: No less than 5 applicants have submitted applications to the DEPARTMENT OF MINING for the right to build an open-cast tungsten and molybdenum mine, one of these 50 hectares in extent and 200 metres deep, in the Moutonshoek Valley, between Piketberg and Elands Bay in the Western Cape. The Moutonshoek is a narrow valley, approximately 17 kilometres long and 3-4 kilometres wide, on the slopes of the Piketberg-mountain. THE VERLORENVLEI COALITION will oppose the proposed mining because: 1. It will destroy productive and profitable farms and detrimentally affect the food security of the Western Cape. -

Hessequa Municipality

GRDM Rep Forum January 2020 HESSEQUA MUNICIPALITY Introduction DEMOGRAPHICS & INSTITUTIONAL INFO Town Growth Rate 2018 Albertinia 3.11% 8393 Gouritsmond 1.16% 539 Jongensfontein 2.33% 389 Heidelberg 1.49% 8762 Towns Melkhoutfontein 5.53% 3141 & Riversdal 2.37% 19982 Slangrivier 2.50% 3324 Growth Stilbaai 1.55% 3737 Witsand 4.90% 389 Rural -0.13% 11525 Total 1.78% 78020 10.0% Load-shedding Aftermath of global financial crisis and domestic Declines in tourism 8.0% electricity crises Commodity price 6.0% Load-shedding Load-shedding SA in recession 4.0% 2.0% 0.0% 2010 FIFA World Cup -2.0% Deepening drought -4.0% 2018 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 e Kannaland 9.1% -1.4% 1.0% 3.0% 2.6% 2.7% 3.7% 1.3% 0.0% 3.1% 1.1% Hessequa 6.8% -0.6% 1.5% 3.4% 2.9% 3.0% 3.1% 1.2% 0.1% 2.3% 0.4% Mossel Bay 3.5% -0.5% 2.0% 4.2% 3.2% 2.5% 2.1% 1.0% 0.9% 1.1% 0.2% George 5.2% -0.3% 2.7% 4.3% 3.5% 3.2% 2.9% 2.1% 1.5% 1.7% 1.6% Oudtshoorn 5.3% -0.6% 2.3% 3.5% 3.0% 3.1% 2.7% 1.3% 0.7% 1.5% 1.1% Bitou 4.5% 0.1% 2.2% 3.3% 2.8% 3.3% 2.4% 1.5% 1.2% 1.3% -0.6% Knysna 3.4% -0.3% 1.1% 2.5% 2.3% 2.0% 1.9% 0.9% 0.5% 0.8% -0.9% Garden Route District 4.9% -0.4% 2.1% 3.8% 3.1% 2.9% 2.6% 1.5% 1.0% 1.5% 0.8% Western Cape Province 4.1% -1.3% 2.3% 3.8% 2.9% 2.6% 2.4% 1.4% 1.1% 1.2% 0.9% Access to Services & Economic Sectors Unemployment Institutional Overview Senior Management Experienced and Stable Technical Director Appointment Process is underway 6th Clean Audit Outcome Challenge to Comply with existing resources – No new posts can be funded – Cost of Services Risk Driven IDP & Budget Process Investment in Growth Infrastructure Addressing Backlogs Mitigating Risk: Fire & ICT Expenditure Information CAPEX & OPEX OVERVIEW Projects & Programmes - 1 Capital Expenditure challenge has been resolved: Multi- year tender for appointment of Civil Engineers successfully completed CAPEX reported on S72 Report as 13.8% Commitments already registered on System, as projects are completed the expenditure will increase drastically. -

Western Cape Provincial Crime Analysis Report 2015/16

Western Cape Provincial Crime Analysis Report 2015/16 Analysis of crime based on the 2015/16 crime statistics issued by the South African Police Service on the 2nd of September 2016 Department of Community Safety Provincial Secretariat for Safety and Security CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION AND CONTEXTUAL BACKGROUND 2 1.1 Limitations of crime statistics 2 2. METHODOLOGICAL APPROACH 3 3. KEY FINDINGS: 2014/15 - 2015/16 4 4. CONTACT CRIME ANALYSIS 6 4.1 Murder 6 4.2 Attempted murder 10 4.3 Total sexual crimes 13 4.4 Assault GBH 15 4.5 Common assault 18 4.6 Common robbery 20 4.7 Robbery with aggravating circumstances 22 4.8 Summary of violent crime in the Province 25 5. PROPERTY-RELATED CRIME 26 5.1 Burglary at non-residential premises 26 5.2 Burglary at residential premises 29 5.3 Theft of motor vehicle and motorcycle 32 5.4 Theft out of or from motor vehicle 34 5.5 Stock-theft 36 6. SUMMARY: 17 COMMUNITY-REPORTED SERIOUS CRIMES 37 6.1 17 Community-reported serious crimes 37 7. CRIME DETECTED AS A RESULT OF POLICE ACTION 38 7.1 Illegal possession of firearms and ammunition 38 7.2 Drug-related crime 43 7.3 Driving under the influence of alcohol or drugs 46 8. TRIO CRIMES 48 8.1 Car-jacking 48 8.2 Robbery at residential premises 50 8.3 Robbery at non-residential premises 53 9. CONCLUSION 56 Western Cape Provincial Crime Analysis Report 1 1. INTRODUCTION AND CONTEXTUAL BACKGROUND The South African Police Service (SAPS) annually releases reported and recorded crime statistics for the preceding financial year i.e. -

7. Water Quality

Western Cape IWRM Action Plan: Status Quo Report Final Draft 7. WATER QUALITY 7.1 INTRODUCTION 7.1.1 What is water quality? “Water quality” is a term used to express the suitability of water to sustain various uses, such as agricultural, domestic, recreational, and industrial, or aquatic ecosystem processes. A particular use or process will have certain requirements for the physical, chemical, or biological characteristics of water; for example limits on the concentrations of toxic substances for drinking water use, or restrictions on temperature and pH ranges for water supporting invertebrate communities. Consequently, water quality can be defined by a range of variables which limit water use by comparing the physical and chemical characteristics of a water sample with water quality guidelines or standards. Although many uses have some common requirements for certain variables, each use will have its own demands and influences on water quality. Water quality is neither a static condition of a system, nor can it be defined by the measurement of only one parameter. Rather, it is variable in both time and space and requires routine monitoring to detect spatial patterns and changes over time. The composition of surface and groundwater is dependent on natural factors (geological, topographical, meteorological, hydrological, and biological) in the drainage basin and varies with seasonal differences in runoff volumes, weather conditions, and water levels. Large natural variations in water quality may, therefore, be observed even where only a single water resource is involved. Human intervention also has significant effects on water quality. Some of these effects are the result of hydrological changes, such as the building of dams, draining of wetlands, and diversion of flow. -

Sea Level Rise and Flood Risk Assessment for a Select Disaster Prone Area Along the Western Cape Coast

Department of Environmental Affairs and Development Planning Sea Level Rise and Flood Risk Assessment for a Select Disaster Prone Area Along the Western Cape Coast Phase 2 Report: Eden District Municipality Sea Level Rise and Flood Risk Modelling Final May 2010 REPORT TITLE : Phase 2 Report: Eden District Municipality Sea Level Rise and Flood Risk Modelling CLIENT : Provincial Government of the Western Cape Department of Environmental Affairs and Development Planning: Strategic Environmental Management PROJECT : Sea Level Rise and Flood Risk Assessment for a Select Disaster Prone Area Along the Western Cape Coast AUTHORS : D. Blake N. Chimboza REPORT STATUS : Final REPORT NUMBER : 769/2/1/2010 DATE : May 2010 APPROVED FOR : S. Imrie D. Blake Project Manager Task Leader This report is to be referred to in bibliographies as: Umvoto Africa. (2010). Sea Level Rise and Flood Risk Assessment for a Select Disaster Prone Area Along the Western Cape Coast. Phase 2 Report: Eden District Municipality Sea Level Rise and Flood Risk Modelling. Prepared by Umvoto Africa (Pty) Ltd for the Provincial Government of the Western Cape Department of Environmental Affairs and Development Planning: Strategic Environmental Management (May 2010). Phase 2: Eden DM Sea Level Rise and Flood Risk Modelling 2010 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY INTRODUCTION Umvoto Africa (Pty) Ltd was appointed by the Western Cape Department of Environmental Affairs and Development Planning (DEA&DP): Strategic Environmental Management division to undertake a sea level rise and flood risk assessment for a select disaster prone area along the Western Cape coast, namely the portion of coastline covered by the Eden District (DM) Municipality, from Witsand to Nature’s Valley. -

Heritage Impact Assessment Proposed Afrisam Cement Plant, Mine and Associated Infrastructure in Saldanha, Western Cape

HERITAGE IMPACT ASSESSMENT PROPOSED AFRISAM CEMENT PLANT, MINE AND ASSOCIATED INFRASTRUCTURE IN SALDANHA, WESTERN CAPE As part of the Environmental Impact Assessment Prepared for Aurecon South Africa (Pty) Ltd On behalf of Afrisam (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd September 2011 Prepared by: David Halkett ACO Associates cc 8 Jacobs Ladder St James 7945 Phone 0731418606 Email: [email protected] 1 DECLARATION by the independent person who compiled a specialist report or undertook a specialist process I …David John Halkett…………………………………, as the appointed independent specialist hereby declare that I: act/ed as the independent specialist in this application; regard the information contained in this report as it relates to my specialist input /study to be true and correct, and do not have and will not have any financial interest in the undertaking of the activity, other than remuneration for work performed in terms of the NEMA, the Environmental Impact Assessment Regulations, 2010 and any specific environmental management Act; have and will not have no vested interest in the proposed activity proceeding; have disclosed, to the applicant, EAP and competent authority, any material information that have or may have the potential to influence the decision of the competent authority or the objectivity of any report, plan or document required in terms of the NEMA, the Environmental Impact Assessment Regulations, 2010 and any specific environmental management Act; am fully aware of and meet the responsibilities in terms of NEMA, the Environmental Impact Assessment Regulations, 2010 (specifically in terms of regulation 17 of GN No. R. 543) and any specific environmental management Act, and that failure to comply with these requirements may constitute and result in disqualification; have provided the competent authority with access to all information at my disposal regarding the application, whether such information is favourable to the applicant or not; and am aware that a false declaration is an offence in terms of regulation 71 of GN No.