Arxiv:Astro-Ph/9508054V2 13 Sep 1995

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Winter Constellations

Winter Constellations *Orion *Canis Major *Monoceros *Canis Minor *Gemini *Auriga *Taurus *Eradinus *Lepus *Monoceros *Cancer *Lynx *Ursa Major *Ursa Minor *Draco *Camelopardalis *Cassiopeia *Cepheus *Andromeda *Perseus *Lacerta *Pegasus *Triangulum *Aries *Pisces *Cetus *Leo (rising) *Hydra (rising) *Canes Venatici (rising) Orion--Myth: Orion, the great hunter. In one myth, Orion boasted he would kill all the wild animals on the earth. But, the earth goddess Gaia, who was the protector of all animals, produced a gigantic scorpion, whose body was so heavily encased that Orion was unable to pierce through the armour, and was himself stung to death. His companion Artemis was greatly saddened and arranged for Orion to be immortalised among the stars. Scorpius, the scorpion, was placed on the opposite side of the sky so that Orion would never be hurt by it again. To this day, Orion is never seen in the sky at the same time as Scorpius. DSO’s ● ***M42 “Orion Nebula” (Neb) with Trapezium A stellar nursery where new stars are being born, perhaps a thousand stars. These are immense clouds of interstellar gas and dust collapse inward to form stars, mainly of ionized hydrogen which gives off the red glow so dominant, and also ionized greenish oxygen gas. The youngest stars may be less than 300,000 years old, even as young as 10,000 years old (compared to the Sun, 4.6 billion years old). 1300 ly. 1 ● *M43--(Neb) “De Marin’s Nebula” The star-forming “comma-shaped” region connected to the Orion Nebula. ● *M78--(Neb) Hard to see. A star-forming region connected to the Orion Nebula. -

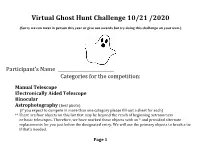

Ghost Hunt Challenge 2020

Virtual Ghost Hunt Challenge 10/21 /2020 (Sorry we can meet in person this year or give out awards but try doing this challenge on your own.) Participant’s Name _________________________ Categories for the competition: Manual Telescope Electronically Aided Telescope Binocular Astrophotography (best photo) (if you expect to compete in more than one category please fill-out a sheet for each) ** There are four objects on this list that may be beyond the reach of beginning astronomers or basic telescopes. Therefore, we have marked these objects with an * and provided alternate replacements for you just below the designated entry. We will use the primary objects to break a tie if that’s needed. Page 1 TAS Ghost Hunt Challenge - Page 2 Time # Designation Type Con. RA Dec. Mag. Size Common Name Observed Facing West – 7:30 8:30 p.m. 1 M17 EN Sgr 18h21’ -16˚11’ 6.0 40’x30’ Omega Nebula 2 M16 EN Ser 18h19’ -13˚47 6.0 17’ by 14’ Ghost Puppet Nebula 3 M10 GC Oph 16h58’ -04˚08’ 6.6 20’ 4 M12 GC Oph 16h48’ -01˚59’ 6.7 16’ 5 M51 Gal CVn 13h30’ 47h05’’ 8.0 13.8’x11.8’ Whirlpool Facing West - 8:30 – 9:00 p.m. 6 M101 GAL UMa 14h03’ 54˚15’ 7.9 24x22.9’ 7 NGC 6572 PN Oph 18h12’ 06˚51’ 7.3 16”x13” Emerald Eye 8 NGC 6426 GC Oph 17h46’ 03˚10’ 11.0 4.2’ 9 NGC 6633 OC Oph 18h28’ 06˚31’ 4.6 20’ Tweedledum 10 IC 4756 OC Ser 18h40’ 05˚28” 4.6 39’ Tweedledee 11 M26 OC Sct 18h46’ -09˚22’ 8.0 7.0’ 12 NGC 6712 GC Sct 18h54’ -08˚41’ 8.1 9.8’ 13 M13 GC Her 16h42’ 36˚25’ 5.8 20’ Great Hercules Cluster 14 NGC 6709 OC Aql 18h52’ 10˚21’ 6.7 14’ Flying Unicorn 15 M71 GC Sge 19h55’ 18˚50’ 8.2 7’ 16 M27 PN Vul 20h00’ 22˚43’ 7.3 8’x6’ Dumbbell Nebula 17 M56 GC Lyr 19h17’ 30˚13 8.3 9’ 18 M57 PN Lyr 18h54’ 33˚03’ 8.8 1.4’x1.1’ Ring Nebula 19 M92 GC Her 17h18’ 43˚07’ 6.44 14’ 20 M72 GC Aqr 20h54’ -12˚32’ 9.2 6’ Facing West - 9 – 10 p.m. -

Experiencing Hubble

PRESCOTT ASTRONOMY CLUB PRESENTS EXPERIENCING HUBBLE John Carter August 7, 2019 GET OUT LOOK UP • When Galaxies Collide https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HP3x7TgvgR8 • How Hubble Images Get Color https://www.youtube.com/watch? time_continue=3&v=WSG0MnmUsEY Experiencing Hubble Sagittarius Star Cloud 1. 12,000 stars 2. ½ percent of full Moon area. 3. Not one star in the image can be seen by the naked eye. 4. Color of star reflects its surface temperature. Eagle Nebula. M 16 1. Messier 16 is a conspicuous region of active star formation, appearing in the constellation Serpens Cauda. This giant cloud of interstellar gas and dust is commonly known as the Eagle Nebula, and has already created a cluster of young stars. The nebula is also referred to the Star Queen Nebula and as IC 4703; the cluster is NGC 6611. With an overall visual magnitude of 6.4, and an apparent diameter of 7', the Eagle Nebula's star cluster is best seen with low power telescopes. The brightest star in the cluster has an apparent magnitude of +8.24, easily visible with good binoculars. A 4" scope reveals about 20 stars in an uneven background of fainter stars and nebulosity; three nebulous concentrations can be glimpsed under good conditions. Under very good conditions, suggestions of dark obscuring matter can be seen to the north of the cluster. In an 8" telescope at low power, M 16 is an impressive object. The nebula extends much farther out, to a diameter of over 30'. It is filled with dark regions and globules, including a peculiar dark column and a luminous rim around the cluster. -

Implications of a Hot Atmosphere/Corino from ALMA Observations Toward NGC 1333 IRAS 4A1

The Astrophysical Journal, 872:196 (14pp), 2019 February 20 https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-4357/aaffda © 2019. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. Implications of a Hot Atmosphere/Corino from ALMA Observations toward NGC 1333 IRAS 4A1 Dipen Sahu1,2,3, Sheng-Yuan Liu2 , Yu-Nung Su2, Zhi-Yun Li4, Chin-Fei Lee2 , Naomi Hirano2, and Shigehisa Takakuwa2,5 1 Indian Institute of Astrophysics, Sarjapur Main Road, 2nd Block, Koramangala, Bangalore-560034, India; [email protected] 2 Academia Sinica Institute of Astronomy and Astrophysics, 11F of AS/NTU Astronomy-Mathematics Building, No.1, Section 4, Roosevelt Rd, Taipei 10617, Taiwan, R.O.C. 3 Physical Research Laboratory, Ahmedabad-380009, India 4 Astronomy Department, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA 22904, USA 5 Department of Physics and Astronomy, Graduate School of Science and Engineering, Kagoshima University, 1-21-35 Korimoto, Kagoshima 890-0065, Japan Received 2018 October 24; revised 2019 January 14; accepted 2019 January 16; published 2019 February 25 Abstract We report high angular resolution observations of NGC 1333 IRAS 4A, a protostellar binary including A1 and A2, at 0.84mm with the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array. From the continuum observations, we suggest that the dust emission from the A1 core is optically thick, and A2 is predominantly optically thin. The A2 core, exhibiting a forest of spectral lines including complex molecules, is a well-known hot corino, as suggested by previous works. More importantly, we report, for the first time, solid evidence of complex organic molecules 13 (COMs), including CH3OH, CH3OH, CH2DOH, and CH3CHO, associated with the A1 core seen in absorption. -

A Basic Requirement for Studying the Heavens Is Determining Where In

Abasic requirement for studying the heavens is determining where in the sky things are. To specify sky positions, astronomers have developed several coordinate systems. Each uses a coordinate grid projected on to the celestial sphere, in analogy to the geographic coordinate system used on the surface of the Earth. The coordinate systems differ only in their choice of the fundamental plane, which divides the sky into two equal hemispheres along a great circle (the fundamental plane of the geographic system is the Earth's equator) . Each coordinate system is named for its choice of fundamental plane. The equatorial coordinate system is probably the most widely used celestial coordinate system. It is also the one most closely related to the geographic coordinate system, because they use the same fun damental plane and the same poles. The projection of the Earth's equator onto the celestial sphere is called the celestial equator. Similarly, projecting the geographic poles on to the celest ial sphere defines the north and south celestial poles. However, there is an important difference between the equatorial and geographic coordinate systems: the geographic system is fixed to the Earth; it rotates as the Earth does . The equatorial system is fixed to the stars, so it appears to rotate across the sky with the stars, but of course it's really the Earth rotating under the fixed sky. The latitudinal (latitude-like) angle of the equatorial system is called declination (Dec for short) . It measures the angle of an object above or below the celestial equator. The longitud inal angle is called the right ascension (RA for short). -

Lecture 2, Galaxy Number Counts and Luminosity Functions

Galaxies 626 Lecture 2: Galaxy number counts and luminosity functions How much of the extragalactic background light can we identify, and how much is unidentified (unresolved)? The next step is to count all the galaxies we can find and see how much light they contain So we now want to form the galaxy number counts at all wavelengths B, R, z/ 15/ x 15/ B (1.7hrs) R (5.2hrs) z’ (3.9hrs) B (27) R (26.4) z’ (25.4) Optical Image Capak et al. 2003 Measuring Galaxy Luminosities Galaxies, unlike stars, are not point sources The Hubble Space Telescope can resolve (i.e. detect the extended nature of) essentially all galaxies Even from the ground, most galaxies can easily be distinguished from stars morphologically and on the basis of their colors Measuring Galaxy Luminosities Define the surface brightness of a galaxy I as the amount of light from the galaxy per square arcsecond on the sky Consider a small square patch, of side D, in a galaxy at distance d: d D Angle patch subtends on sky α = D/d Finding Galaxies in an Image Finding galaxies in an image and constructing the number counts is the subject of the first student project Essentially we look for all objects above a limiting surface brightness and covering more than a specified area SExtractor is a commonly used package 20 cm Radio Image from the VLA Number Counts We then need to measure the fluxes of all the objects that we find The number counts are simply the number of objects we find in a given flux or magnitude bin per unit area of the sky Measuring Galaxy Luminosities Consider again -

Structure Analysis of the Perseus and the Cepheus B Molecular Clouds

Structure analysis of the Perseus and the Cepheus B molecular clouds Inaugural-Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades der Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakult¨at der Universit¨at zu K¨oln vorgelegt von Kefeng Sun aus VR China Koln,¨ 2008 Berichterstatter : Prof. Dr. J¨urgen Stutzki Prof. Dr. Andreas Zilges Tag der letzten m¨undlichen Pr¨ufung : 26.06.2008 To my parents and Jiayu Contents Abstract i Zusammenfassung v 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Overviewoftheinterstellarmedium . 1 1.1.1 Historicalstudiesoftheinterstellarmedium . .. 1 1.1.2 ThephasesoftheISM .. .. .. .. .. 2 1.1.3 Carbonmonoxidemolecularclouds . 3 1.2 DiagnosticsofturbulenceinthedenseISM . 4 1.2.1 The ∆-variancemethod.. .. .. .. .. 6 1.2.2 Gaussclumps ........................ 8 1.3 Photondominatedregions . 9 1.3.1 PDRmodels ........................ 12 1.4 Outline ............................... 12 2 Previous studies 14 2.1 ThePerseusmolecularcloud . 14 2.2 TheCepheusBmolecularcloud . 16 3 Large scale low -J CO survey of the Perseus cloud 18 3.1 Observations ............................ 18 3.2 DataSets .............................. 21 3.2.1 Integratedintensitymaps. 21 3.2.2 Velocitystructure. 24 3.3 The ∆-varianceanalysis. 24 3.3.1 Integratedintensitymaps. 27 3.3.2 Velocitychannelmaps . 30 3.4 Discussion.............................. 34 3.4.1 Integratedintensitymaps. 34 3.4.2 Velocitychannelmaps . 34 I II CONTENTS 3.5 Summary .............................. 38 4 The Gaussclumps analysis in the Perseus cloud 40 4.1 Resultsanddiscussions . 40 4.1.1 Clumpmass......................... 41 4.1.2 Clumpmassspectra . 42 4.1.3 Relationsofclumpsizewithlinewidthandmass . 46 4.1.4 Equilibriumstateoftheclumps . 49 4.2 Summary .............................. 53 5 Study of the photon dominated region in the IC 348 cloud 55 5.1 Datasets............................... 56 5.1.1 [C I] and 12CO4–3observationswithKOSMA . 56 5.1.2 Complementarydatasets. -

Et Al, ‘How Do Stars Gain Their Mass? a JCMT/SCUBA-2 Transient Survey of Protostars in Nearby Star- Forming Regions’, the Astrophysical Journal, Vol

Research Archive Citation for published version: Gregory J. Herczeg, et al, ‘How Do Stars Gain Their Mass? A JCMT/SCUBA-2 Transient Survey of Protostars in Nearby Star- forming Regions’, The Astrophysical Journal, Vol. 849 (43), October 2017. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-4357/aa8b62 Document Version: This is the Accepted Manuscript version. The version in the University of Hertfordshire Research Archive may differ from the final published version. Copyright and Reuse: © 2017 The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. Content in the UH Research Archive is made available for personal research, educational, and non-commercial purposes only. Unless otherwise stated, all content is protected by copyright, and in the absence of an open license, permissions for further re-use should be sought from the publisher, the author, or other copyright holder. Enquiries If you believe this document infringes copyright, please contact the Research & Scholarly Communications Team at [email protected] Draft version September 8, 2017 Preprint typeset using LATEX style emulateapj v. 01/23/15 HOW DO STARS GAIN THEIR MASS? A JCMT/SCUBA-2 TRANSIENT SURVEY OF PROTOSTARS IN NEARBY STAR FORMING REGIONS Gregory J. Herczeg1, Doug Johnstone2,3, Steve Mairs2,3, Jennifer Hatchell4, Jeong-Eun Lee5, Geoffrey C. Bower6, Huei-Ru Vivien Chen7, Yuri Aikawa8, Hyunju Yoo9,5, Sung-Ju Kang10, Miju Kang10, Wen-Ping Chen11, Jonathan P. Williams12, Jaehan Bae13, Michael M. Dunham14,15, Eduard I. Vorobiov16,17,18, Zhaohuan Zhu19, Ramprasad Rao20, Helen Kirk2, Satoko Takahashi21,22, Oscar Morata20, Kevin Lacaille23, James Lane3, Andy Pon24, Aleks Scholz25, Manash R. Samal11, Graham S. -

Surface Brightness Profiles

AST222 Winter 2006 Supplementary Notes: Galaxy Surface Brightness Pro¯les The fundamental way we characterize the morphology of galaxies is through their surface brightness pro¯les. The light from galaxies follows a distribution of brightness on the night sky given by I(x; y) where I is the intensity or surface brightness distribution measured in units of luminosity per unit area at position (x; y) where the area is either in physical units (pc2) or an angular area in square arcseconds. The intensity is often represented by a radially-averaged function, I(R). The total luminosity of a galaxy is then just: 1 Ltot = 2¼ I(R)RdR (1) Z0 Astronomers usually quote surface brightness in units of magnitudes per square arcsec denoted by the symbol ¹. The quantity ¹ represents the apparent magnitude of the equivalent total light observed in a square arcsecond at di®erent points in the distribution. It can be related to the physical surface brightness pro¯le through: ¹ = 2:5 log10 I + C (2) ¡ ¡2 If I is measured in L¯ pc then the constant C can be found by going back to the distance modulus formula and determining the amount of light in a square arcsec for a galaxy observed at distance d (in pc) i.e. the light in a sq. arcsec is: L = Id2±2 (3) where ± = 1" = 1=206265 radians. The distance modulus formula is: m = M + 5 log10 d=(1pc) 5 (4) ¡ where M is the absolute magnitude of the star given in terms of the solar absolute magnitude M¯ by: M = 2:5 log10 L=L¯ + M¯ (5) ¡ (M¯ is the absolute magnitude of the sun not to be confused with the solar mass). -

The Number, Luminosity, and Mass Density of Spiral Galaxies As

The numb er luminosity and mass density of spiral galaxies as a function of surface brightness Stacy S McGaugh Institute of Astronomy University of Cambridge Madingley Road Cambridge CB HA ABSTRACT I give analytic expressions for the relative numb er luminosity and mass density of disc galaxies as a function of surface brightness These surface brightness distributions are asymmetric with long tails to lower surface brightnesses This asymmetry induces systematic errors in most determinations of the galaxy luminosity function Galaxies of low surface brightness exist in large numb ers but the additional contribution to the integrated luminosity density is mo dest probably Key words galaxies formation galaxies fundamental parameters galaxies general galaxies luminosity function mass function galaxies spiral galaxies structure Accepted for publication in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society Present address Department of Terrestrial Magnetism Carnegie Institution of Wash ington Broad Branch Road NW Washington DC USA INTRODUCTION The space density of Low Surface Brightness LSB galaxies has long b een a contro versial and confusing sub ject It is basic to our inventory of the contents of the universe and is crucial to many asp ects of extragalactic astronomy For example the density of LSB galaxies has an impact on the luminosity function faint galaxy numb er counts Ly absorption systems and theories of galaxy formation In this pap er I derive analytic expressions which quantify the density of discs of all surface -

The Cosmic Distance Scale • Distance Information Is Often Crucial to Understand the Physics of Astrophysical Objects

The cosmic distance scale • Distance information is often crucial to understand the physics of astrophysical objects. This requires knowing the basic properties of such an object, like its size, its environment, its location in space... • There are essentially two ways to derive distances to astronomical objects, through absolute distance estimators or through relative distance estimators • Absolute distance estimators Objects for whose distance can be measured directly. They have physical properties which allow such a measurement. Examples are pulsating stars, supernovae atmospheres, gravitational lensing time delays from multiple quasar images, etc. • Relative distance estimators These (ultimately) depend on directly measured distances, and are based on the existence of types of objects that share the same intrinsic luminosity (and whose distance has been determined somehow). For example, there are types of stars that have all the same intrinsic luminosity. If the distance to a sample of these objects has been measured directly (e.g. through trigonometric parallax), then we can use these to determine the distance to a nearby galaxy by comparing their apparent brightness to those in the Milky Way. Essentially we use that log(D1/D2) = 1/5 * [(m1 –m2) - (A1 –A2)] where D1 is the distance to system 1, D2 is the distance to system 2, m1 is the apparent magnitudes of stars in S1 and S2 respectively, and A1 and A2 corrects for the absorption towards the sources in S1 and S2. Stars or objects which have the same intrinsic luminosity are known as standard candles. If the distance to such a standard candle has been measured directly, then the relative distances will have been anchored to an absolute distance scale. -

Open Clusters in APOGEE and GALAH Combining Gaia and Ground-Based Spectroscopic Surveys?

A&A 623, A80 (2019) Astronomy https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201834546 & c ESO 2019 Astrophysics Open clusters in APOGEE and GALAH Combining Gaia and ground-based spectroscopic surveys? R. Carrera1, A. Bragaglia2, T. Cantat-Gaudin3, A. Vallenari1, L. Balaguer-Núñez3, D. Bossini1, L. Casamiquela4, C. Jordi3, R. Sordo1, and C. Soubiran4 1 INAF-Osservatorio Astronomico di Padova, vicolo dell’Osservatorio 5, 35122 Padova, Italy e-mail: [email protected] 2 INAF-Osservatorio di Astrofisica e Scienza dello Spazio, via P. Gobetti 93/3, 40129 Bologna, Italy 3 Institut de Ciències del Cosmos, Universitat de Barcelona (IEEC-UB), Martí i Franquès 1, 08028 Barcelona, Spain 4 Laboratoire d’Astrophysique de Bordeaux, Univ. Bordeaux, CNRS, B18N, allée Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, 33615 Pessac, France Received 31 October 2018 / Accepted 26 January 2019 ABSTRACT Context. Open clusters are ideal laboratories to investigate a variety of astrophysical topics, from the properties of the Galactic disc to stellar-evolution models. Knowing their metallicity and possibly detailed chemical abundances is therefore important. However, the number of systems with chemical abundances determined from high-resolution spectroscopy remains small. Aims. Our aim is to increase the number of open clusters with radial velocities and chemical abundances determined from high- resolution spectroscopy using publicly available catalogues of surveys in combination with Gaia data. Methods. Open cluster stars have been identified in the APOGEE and GALAH spectroscopic surveys by cross-matching their latest data releases with stars for which high-probability astrometric membership has been derived in many clusters on the basis of the Gaia second data release.