Arxiv:1808.10438V1 [Astro-Ph.SR] 30 Aug 2018 Are Similar to the Radii of Known Class 0 Disks with Detected Keplerian Rotation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Winter Constellations

Winter Constellations *Orion *Canis Major *Monoceros *Canis Minor *Gemini *Auriga *Taurus *Eradinus *Lepus *Monoceros *Cancer *Lynx *Ursa Major *Ursa Minor *Draco *Camelopardalis *Cassiopeia *Cepheus *Andromeda *Perseus *Lacerta *Pegasus *Triangulum *Aries *Pisces *Cetus *Leo (rising) *Hydra (rising) *Canes Venatici (rising) Orion--Myth: Orion, the great hunter. In one myth, Orion boasted he would kill all the wild animals on the earth. But, the earth goddess Gaia, who was the protector of all animals, produced a gigantic scorpion, whose body was so heavily encased that Orion was unable to pierce through the armour, and was himself stung to death. His companion Artemis was greatly saddened and arranged for Orion to be immortalised among the stars. Scorpius, the scorpion, was placed on the opposite side of the sky so that Orion would never be hurt by it again. To this day, Orion is never seen in the sky at the same time as Scorpius. DSO’s ● ***M42 “Orion Nebula” (Neb) with Trapezium A stellar nursery where new stars are being born, perhaps a thousand stars. These are immense clouds of interstellar gas and dust collapse inward to form stars, mainly of ionized hydrogen which gives off the red glow so dominant, and also ionized greenish oxygen gas. The youngest stars may be less than 300,000 years old, even as young as 10,000 years old (compared to the Sun, 4.6 billion years old). 1300 ly. 1 ● *M43--(Neb) “De Marin’s Nebula” The star-forming “comma-shaped” region connected to the Orion Nebula. ● *M78--(Neb) Hard to see. A star-forming region connected to the Orion Nebula. -

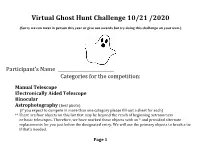

Ghost Hunt Challenge 2020

Virtual Ghost Hunt Challenge 10/21 /2020 (Sorry we can meet in person this year or give out awards but try doing this challenge on your own.) Participant’s Name _________________________ Categories for the competition: Manual Telescope Electronically Aided Telescope Binocular Astrophotography (best photo) (if you expect to compete in more than one category please fill-out a sheet for each) ** There are four objects on this list that may be beyond the reach of beginning astronomers or basic telescopes. Therefore, we have marked these objects with an * and provided alternate replacements for you just below the designated entry. We will use the primary objects to break a tie if that’s needed. Page 1 TAS Ghost Hunt Challenge - Page 2 Time # Designation Type Con. RA Dec. Mag. Size Common Name Observed Facing West – 7:30 8:30 p.m. 1 M17 EN Sgr 18h21’ -16˚11’ 6.0 40’x30’ Omega Nebula 2 M16 EN Ser 18h19’ -13˚47 6.0 17’ by 14’ Ghost Puppet Nebula 3 M10 GC Oph 16h58’ -04˚08’ 6.6 20’ 4 M12 GC Oph 16h48’ -01˚59’ 6.7 16’ 5 M51 Gal CVn 13h30’ 47h05’’ 8.0 13.8’x11.8’ Whirlpool Facing West - 8:30 – 9:00 p.m. 6 M101 GAL UMa 14h03’ 54˚15’ 7.9 24x22.9’ 7 NGC 6572 PN Oph 18h12’ 06˚51’ 7.3 16”x13” Emerald Eye 8 NGC 6426 GC Oph 17h46’ 03˚10’ 11.0 4.2’ 9 NGC 6633 OC Oph 18h28’ 06˚31’ 4.6 20’ Tweedledum 10 IC 4756 OC Ser 18h40’ 05˚28” 4.6 39’ Tweedledee 11 M26 OC Sct 18h46’ -09˚22’ 8.0 7.0’ 12 NGC 6712 GC Sct 18h54’ -08˚41’ 8.1 9.8’ 13 M13 GC Her 16h42’ 36˚25’ 5.8 20’ Great Hercules Cluster 14 NGC 6709 OC Aql 18h52’ 10˚21’ 6.7 14’ Flying Unicorn 15 M71 GC Sge 19h55’ 18˚50’ 8.2 7’ 16 M27 PN Vul 20h00’ 22˚43’ 7.3 8’x6’ Dumbbell Nebula 17 M56 GC Lyr 19h17’ 30˚13 8.3 9’ 18 M57 PN Lyr 18h54’ 33˚03’ 8.8 1.4’x1.1’ Ring Nebula 19 M92 GC Her 17h18’ 43˚07’ 6.44 14’ 20 M72 GC Aqr 20h54’ -12˚32’ 9.2 6’ Facing West - 9 – 10 p.m. -

Implications of a Hot Atmosphere/Corino from ALMA Observations Toward NGC 1333 IRAS 4A1

The Astrophysical Journal, 872:196 (14pp), 2019 February 20 https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-4357/aaffda © 2019. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. Implications of a Hot Atmosphere/Corino from ALMA Observations toward NGC 1333 IRAS 4A1 Dipen Sahu1,2,3, Sheng-Yuan Liu2 , Yu-Nung Su2, Zhi-Yun Li4, Chin-Fei Lee2 , Naomi Hirano2, and Shigehisa Takakuwa2,5 1 Indian Institute of Astrophysics, Sarjapur Main Road, 2nd Block, Koramangala, Bangalore-560034, India; [email protected] 2 Academia Sinica Institute of Astronomy and Astrophysics, 11F of AS/NTU Astronomy-Mathematics Building, No.1, Section 4, Roosevelt Rd, Taipei 10617, Taiwan, R.O.C. 3 Physical Research Laboratory, Ahmedabad-380009, India 4 Astronomy Department, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA 22904, USA 5 Department of Physics and Astronomy, Graduate School of Science and Engineering, Kagoshima University, 1-21-35 Korimoto, Kagoshima 890-0065, Japan Received 2018 October 24; revised 2019 January 14; accepted 2019 January 16; published 2019 February 25 Abstract We report high angular resolution observations of NGC 1333 IRAS 4A, a protostellar binary including A1 and A2, at 0.84mm with the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array. From the continuum observations, we suggest that the dust emission from the A1 core is optically thick, and A2 is predominantly optically thin. The A2 core, exhibiting a forest of spectral lines including complex molecules, is a well-known hot corino, as suggested by previous works. More importantly, we report, for the first time, solid evidence of complex organic molecules 13 (COMs), including CH3OH, CH3OH, CH2DOH, and CH3CHO, associated with the A1 core seen in absorption. -

A Basic Requirement for Studying the Heavens Is Determining Where In

Abasic requirement for studying the heavens is determining where in the sky things are. To specify sky positions, astronomers have developed several coordinate systems. Each uses a coordinate grid projected on to the celestial sphere, in analogy to the geographic coordinate system used on the surface of the Earth. The coordinate systems differ only in their choice of the fundamental plane, which divides the sky into two equal hemispheres along a great circle (the fundamental plane of the geographic system is the Earth's equator) . Each coordinate system is named for its choice of fundamental plane. The equatorial coordinate system is probably the most widely used celestial coordinate system. It is also the one most closely related to the geographic coordinate system, because they use the same fun damental plane and the same poles. The projection of the Earth's equator onto the celestial sphere is called the celestial equator. Similarly, projecting the geographic poles on to the celest ial sphere defines the north and south celestial poles. However, there is an important difference between the equatorial and geographic coordinate systems: the geographic system is fixed to the Earth; it rotates as the Earth does . The equatorial system is fixed to the stars, so it appears to rotate across the sky with the stars, but of course it's really the Earth rotating under the fixed sky. The latitudinal (latitude-like) angle of the equatorial system is called declination (Dec for short) . It measures the angle of an object above or below the celestial equator. The longitud inal angle is called the right ascension (RA for short). -

Structure Analysis of the Perseus and the Cepheus B Molecular Clouds

Structure analysis of the Perseus and the Cepheus B molecular clouds Inaugural-Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades der Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakult¨at der Universit¨at zu K¨oln vorgelegt von Kefeng Sun aus VR China Koln,¨ 2008 Berichterstatter : Prof. Dr. J¨urgen Stutzki Prof. Dr. Andreas Zilges Tag der letzten m¨undlichen Pr¨ufung : 26.06.2008 To my parents and Jiayu Contents Abstract i Zusammenfassung v 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Overviewoftheinterstellarmedium . 1 1.1.1 Historicalstudiesoftheinterstellarmedium . .. 1 1.1.2 ThephasesoftheISM .. .. .. .. .. 2 1.1.3 Carbonmonoxidemolecularclouds . 3 1.2 DiagnosticsofturbulenceinthedenseISM . 4 1.2.1 The ∆-variancemethod.. .. .. .. .. 6 1.2.2 Gaussclumps ........................ 8 1.3 Photondominatedregions . 9 1.3.1 PDRmodels ........................ 12 1.4 Outline ............................... 12 2 Previous studies 14 2.1 ThePerseusmolecularcloud . 14 2.2 TheCepheusBmolecularcloud . 16 3 Large scale low -J CO survey of the Perseus cloud 18 3.1 Observations ............................ 18 3.2 DataSets .............................. 21 3.2.1 Integratedintensitymaps. 21 3.2.2 Velocitystructure. 24 3.3 The ∆-varianceanalysis. 24 3.3.1 Integratedintensitymaps. 27 3.3.2 Velocitychannelmaps . 30 3.4 Discussion.............................. 34 3.4.1 Integratedintensitymaps. 34 3.4.2 Velocitychannelmaps . 34 I II CONTENTS 3.5 Summary .............................. 38 4 The Gaussclumps analysis in the Perseus cloud 40 4.1 Resultsanddiscussions . 40 4.1.1 Clumpmass......................... 41 4.1.2 Clumpmassspectra . 42 4.1.3 Relationsofclumpsizewithlinewidthandmass . 46 4.1.4 Equilibriumstateoftheclumps . 49 4.2 Summary .............................. 53 5 Study of the photon dominated region in the IC 348 cloud 55 5.1 Datasets............................... 56 5.1.1 [C I] and 12CO4–3observationswithKOSMA . 56 5.1.2 Complementarydatasets. -

Et Al, ‘How Do Stars Gain Their Mass? a JCMT/SCUBA-2 Transient Survey of Protostars in Nearby Star- Forming Regions’, the Astrophysical Journal, Vol

Research Archive Citation for published version: Gregory J. Herczeg, et al, ‘How Do Stars Gain Their Mass? A JCMT/SCUBA-2 Transient Survey of Protostars in Nearby Star- forming Regions’, The Astrophysical Journal, Vol. 849 (43), October 2017. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-4357/aa8b62 Document Version: This is the Accepted Manuscript version. The version in the University of Hertfordshire Research Archive may differ from the final published version. Copyright and Reuse: © 2017 The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. Content in the UH Research Archive is made available for personal research, educational, and non-commercial purposes only. Unless otherwise stated, all content is protected by copyright, and in the absence of an open license, permissions for further re-use should be sought from the publisher, the author, or other copyright holder. Enquiries If you believe this document infringes copyright, please contact the Research & Scholarly Communications Team at [email protected] Draft version September 8, 2017 Preprint typeset using LATEX style emulateapj v. 01/23/15 HOW DO STARS GAIN THEIR MASS? A JCMT/SCUBA-2 TRANSIENT SURVEY OF PROTOSTARS IN NEARBY STAR FORMING REGIONS Gregory J. Herczeg1, Doug Johnstone2,3, Steve Mairs2,3, Jennifer Hatchell4, Jeong-Eun Lee5, Geoffrey C. Bower6, Huei-Ru Vivien Chen7, Yuri Aikawa8, Hyunju Yoo9,5, Sung-Ju Kang10, Miju Kang10, Wen-Ping Chen11, Jonathan P. Williams12, Jaehan Bae13, Michael M. Dunham14,15, Eduard I. Vorobiov16,17,18, Zhaohuan Zhu19, Ramprasad Rao20, Helen Kirk2, Satoko Takahashi21,22, Oscar Morata20, Kevin Lacaille23, James Lane3, Andy Pon24, Aleks Scholz25, Manash R. Samal11, Graham S. -

Open Clusters in APOGEE and GALAH Combining Gaia and Ground-Based Spectroscopic Surveys?

A&A 623, A80 (2019) Astronomy https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201834546 & c ESO 2019 Astrophysics Open clusters in APOGEE and GALAH Combining Gaia and ground-based spectroscopic surveys? R. Carrera1, A. Bragaglia2, T. Cantat-Gaudin3, A. Vallenari1, L. Balaguer-Núñez3, D. Bossini1, L. Casamiquela4, C. Jordi3, R. Sordo1, and C. Soubiran4 1 INAF-Osservatorio Astronomico di Padova, vicolo dell’Osservatorio 5, 35122 Padova, Italy e-mail: [email protected] 2 INAF-Osservatorio di Astrofisica e Scienza dello Spazio, via P. Gobetti 93/3, 40129 Bologna, Italy 3 Institut de Ciències del Cosmos, Universitat de Barcelona (IEEC-UB), Martí i Franquès 1, 08028 Barcelona, Spain 4 Laboratoire d’Astrophysique de Bordeaux, Univ. Bordeaux, CNRS, B18N, allée Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, 33615 Pessac, France Received 31 October 2018 / Accepted 26 January 2019 ABSTRACT Context. Open clusters are ideal laboratories to investigate a variety of astrophysical topics, from the properties of the Galactic disc to stellar-evolution models. Knowing their metallicity and possibly detailed chemical abundances is therefore important. However, the number of systems with chemical abundances determined from high-resolution spectroscopy remains small. Aims. Our aim is to increase the number of open clusters with radial velocities and chemical abundances determined from high- resolution spectroscopy using publicly available catalogues of surveys in combination with Gaia data. Methods. Open cluster stars have been identified in the APOGEE and GALAH spectroscopic surveys by cross-matching their latest data releases with stars for which high-probability astrometric membership has been derived in many clusters on the basis of the Gaia second data release. -

Making a Sky Atlas

Appendix A Making a Sky Atlas Although a number of very advanced sky atlases are now available in print, none is likely to be ideal for any given task. Published atlases will probably have too few or too many guide stars, too few or too many deep-sky objects plotted in them, wrong- size charts, etc. I found that with MegaStar I could design and make, specifically for my survey, a “just right” personalized atlas. My atlas consists of 108 charts, each about twenty square degrees in size, with guide stars down to magnitude 8.9. I used only the northernmost 78 charts, since I observed the sky only down to –35°. On the charts I plotted only the objects I wanted to observe. In addition I made enlargements of small, overcrowded areas (“quad charts”) as well as separate large-scale charts for the Virgo Galaxy Cluster, the latter with guide stars down to magnitude 11.4. I put the charts in plastic sheet protectors in a three-ring binder, taking them out and plac- ing them on my telescope mount’s clipboard as needed. To find an object I would use the 35 mm finder (except in the Virgo Cluster, where I used the 60 mm as the finder) to point the ensemble of telescopes at the indicated spot among the guide stars. If the object was not seen in the 35 mm, as it usually was not, I would then look in the larger telescopes. If the object was not immediately visible even in the primary telescope – a not uncommon occur- rence due to inexact initial pointing – I would then scan around for it. -

The Structure Observations. and Dynamics of NGC 1333 from L

—— @A manuscript no. (willbe inserted by hand later) ASTRONOMY ———. AND . - Your thesaurus codes arc: ASTROPHYSICS 09(08.06.2; 09.03.1; 09.13.2; 09.19.1 ; 09.11.1; 09.09.1) ‘L-. n1.3.1995 The structure and dynamics of NGC 1333 from l~~CO and C180 observations. S. Warin’, A. Castcts’, W’.D. 1.angcr2, R.W. Wilson3, and L. Pagani4 1 Laboratoirc d’As(rophysiqrrc, Otrscrvatoirc dc Grcnobk, B. P.53X, F-3 f1041, Grenobk Ccdcx 9, France 2 MS 169-506, Jet Propulsion Laboratory, I’asadcna, CA 91109, lJSA 3 AT&T Bell I.aboratorics, 110}1-1,245, }Iolrndcl, NJ 07733, USA 4 D!? MIRM, Obscrvaloirc dc Paris, 61 avenue dc l’Observatoire, F-75014 Paris, France Rcccivcd, accepted Abstract. ‘his paper prcscnk a study of a derrsc molecular region, NGC 1333, and the relationship of the embedded infrared sources and young stellar objects to the s[ructure of its molecular core. We usc Is(*O and Cl~OJ = ] ..+ oandJ =2 -S ] observations, along with those of CS J = 2 + 1 to characterize the structure of the core, calculate densities and masses. Wc find from our C]*O maps that the COI-C consists of a cavity surrounded by a compressed shell of gas. Many of the infrared and outflow sources in NGC . 1333 arc located in the cavity and the outflow wincls from IRAS2, SSV 13 and several other soul ccs appear to bc responsible for creating the cavi(y and forming the shell. We suggest that sequential star formation is taking place in NGC 1333 with successive generations of young stellar objcc(s providing the energy to expand the cavitj, sweep up the material and compress the shell. -

AMI Radio Continuum Observations of Young Stellar Objects with Known Outflows

Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 000, 1–?? (2012) Printed 11 August 2018 (MN LATEX style file v2.2) AMI radio continuum observations of young stellar objects with known outflows⋆ AMI Consortium: Rachael E. Ainsworth1†, Anna M. M. Scaife2, Tom P. Ray1, Jane V. Buckle3,4, Matthew Davies3, Thomas M. O. Franzen5, Keith J. B. Grainge3,4, Michael P. Hobson3, Natasha Hurley-Walker6, Anthony N. Lasenby3,4, Malak Olamaie3, Yvette C. Perrott3, Guy G. Pooley3, John S. Richer3,4, Carmen Rodr´ıguez-Gonzalvez´ 7, Richard D. E. Saunders3,4, Michel P. Schammel3, Paul F. Scott3, Timothy Shimwell5, David Titterington3, Elizabeth Waldram3. 1 Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, 31 Fitzwilliam Place, Dublin 2, Ireland 2 School of Physics & Astronomy, University of Southampton, Highfield, Southampton, SO17 1BJ 3 Astrophysics Group, Cavendish Laboratory, J J Thomson Avenue, Cambridge, CB3 0HE 4 Kavli Institute for Cosmology, Cambridge, Madingley Road, Cambridge, CB3 0HA 5 CSIRO Astronomy & Space Science, Australia Telescope National Facility, PO Box 76, Epping, NSW 1710, Australia 6 International Centre for Radio Astronomy Research, Curtin Institute of Radio Astronomy, 1 Turner Avenue, Technology Park, Bentley, WA 6845, Australia 7 Spitzer Science Center, MS 220-6, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA 91125 Accepted —; received —; in original form 11 August 2018 ABSTRACT We present 16GHz (1.9cm) deep radio continuum observations made with the Arcminute Microkelvin Imager (AMI) of a sample of low-mass young stars driving jets. We combine these new data with archival information from an extensive literature search to examine spec- tral energy distributions (SEDs) for each source and calculate both the radio and sub-mm spectral indices in two different scenarios: (1) fixing the dust temperature (Td) according to evolutionary class; (2) allowing Td to vary. -

Chandra Study of Young Stellar Objects in the NGC 1333 Star

To appear in the Astrophysical Journal; scheduled for 2002, ApJ, 575 (August 10th) Chandra Study of Young Stellar Objects in the NGC 1333 Star-forming Cloud Konstantin V. Getman1, Eric D. Feigelson1, Leisa Townsley1, John Bally2, Charles J. Lada3, Bo Reipurth4 ABSTRACT NGC 1333, a highly active star formation region within the Perseus molecular cloud complex, has been observed with the ACIS-I detector on board the Chandra X-ray Observatory. In our image with a sensitivity limit of 1028 erg s−1, we ∼ detect 127 X-ray sources, most with sub-arcsecond positional accuracy. While 32 of these sources appear to be foreground stars and extragalactic background, 95 X-ray sources are identified with known cluster members. The X-ray luminosity function of the discovered YSO population spans a range of log L 28.0 to 31.5 x ≃ erg s−1 in the 0.5 8 keV band, and absorption ranges from log N 20 to 23 − H ≃ cm−2. Most of the sources have plasma energies between 0.6 and 3 keV, but a few sources show higher energies up to 7 keV. Comparison with K-band source ∼ counts indicates that we detect all of the known cluster members with K < 12, and about half of members with K > 12. K 11, the peak of the K-band ≃ luminosity function, corresponds to 0.2 0.4 M⊙ stars for a cluster age of 1 − ∼ Myr. arXiv:astro-ph/0204252v1 15 Apr 2002 We detect seven of the twenty known YSOs in NGC 1333 producing jets or molecular outflows as well as one deeply embedded object without outflows. -

One of the Most Useful Accessories an Amateur Can Possess Is One of the Ubiquitous Optical Filters

One of the most useful accessories an amateur can possess is one of the ubiquitous optical filters. Having been accessible previously only to the professional astronomer, they came onto the marker relatively recently, and have made a very big impact. They are useful, but don't think they're the whole answer! They can be a mixed blessing. From reading some of the advertisements in astronomy magazines you would be correct in thinking that they will make hitherto faint and indistinct objects burst into vivid observ ability. They don't. What the manufacturers do not mention is that regardless of the filter used, you will still need dark and transparent skies for the use of the filter to be worthwhile. Don't make the mistake of thinking that using a filter from an urban location will always make objects become clearer. The first and most immediately apparent item on the downside is that in all cases the use of a filter reduces the amount oflight that reaches the eye, often quite sub stantially. The brightness of the field of view and the objects contained therein is reduced. However, what the filter does do is select specific wavelengths of light emitted by an object, which may be swamped by other wavelengths. It does this by suppressing the unwanted wavelengths. This is particularly effective in observing extended objects such as emission nebulae and planetary nebulae. In the former case, use a filter that transmits light around the wavelength of 653.2 nm, which is the spectral line of hydrogen alpha (Ha), and is the wavelength oflight respons ible for the spectacular red colour seen in photographs of emission nebulae.