Homophobic Harassment and Violence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Properties Subject to Enforcement Action

Properties Subject to Enforcement Action Introduction This document contains information provided to NAMA, and/or its group entity subsidiaries, by receivers and other insolvency professionals in relation to properties which have been subject to enforcement in the Republic of Ireland, Northern Ireland and Great Britain. The fact that a property is listed in this document does not necessarily imply that that property is currently on the open market for sale. Insolvency professionals’ rights and obligations are not affected. If you believe that information contained in this document is inaccurate or misleading please contact NAMA at [email protected] and NAMA will correct or clarify the information as necessary. Any query with respect to the sale status of the property or any other matter relating to the facts of the property should be directed to the appointed receiver. The firm of the receiver or other insolvency agent is detailed alongside each specified asset. By using this document you are accepting all the Terms of Use of this document as detailed on the NAMA website (www.nama.ie) and within this document. If you do not agree with anything in these you should not use this document. Terms of Use No Warranty or Liability While every effort is made to ensure that the content of this document is accurate, the document is provided “as is” and NAMA makes no representations or warranties in relation to the accuracy or completeness of the information found in it. While the content of this document is provided in good faith, we do not warrant that the information will be kept up to date, be true and not misleading, accurate, or that the NAMA website (from which this document was sourced) will always (or ever) be available for use. -

Daily Prayer Guide July-Sept 2021.Indd

CEF OF IRELAND Daily Prayer Guide JULY - SEPT 2021 Simon & Jayne Gibson: Give thanks to God JULY 2021 for the opportunity they have to take some Thursday 01/07 time off on holiday with friends. 1–4 Ida Johnston: Pray for the teens camp Jennifer McNeill: Pray that camps will be which started yesterday. Praise God that able to take place in some form this month. some folks have offered online help. Pray If not, pray that some day-events for our for Aud who will do the teaching. young people will be able to be organised. Andrew & Beulah McMullan: Pray that restrictions will not prevent them from Sunday 04/07 ® holding 5–Day Clubs in Co Monaghan and 4–9 Rosalind Patterson: Pray for the North that God will bring along volunteers to help Dublin Junior Camp. Please pray that the reach the children. children will engage in the online camp and attend the Zoom meetings. Pray also Lynda McAuley: Pray for opportunities to for the leaders as they interact with the share the good news of Christ with the boys children. and girls in Ballina. 4–16 Brian & Helen Donaghy: Please pray Friday 02/07 that they will be able to have two weeks of day camps on the beach of Rossnowlagh David and Heather Cowan: Pray that it will with the help of The Surf Project, Exodus be possible to hold 5DCs and Holiday Bible team and two OM leaders. Clubs this summer. Louise Davidson: Praise God for the Brian & Helen Donaghy: Praise God that opportunity to hold a NE Down day camp the Republic of Ireland will hopefully be this summer. -

Speeding in E District for 10 Years

FREEDOM OF INFORMATION REQUEST Request Number: F-2015-02079 Keyword: Operational Policing Subject: Speeding In E District For 10 Years Request and Answer: Question 1 Can you tell us how many people have been caught speeding on the 30mph stretch of the A51 Madden Road near Tandragee Road in the past three years and how many accidents have occurred on this road in the past 10 years? Answer The decision has been taken to disclose the located information to you in full. All data provided in answer to this request is from the Northern Ireland Road Safety Partnership (NIRSP). Between January 2012 and May 2015, 691 people have been detected speeding on the A51 Madden Road, Tandragee. There have been 8 collisions recorded on the Madden Road between its junction with Market Street and where the Madden Road/Tandragee Road meets Whinny Hill. This is for the time period 1st April 2005 to 31st March 2015. One collision resulted in a fatality, one resulted in serious injury and 6 resulted in slight injuries. Question 2 Also can you provide figures for the average amount of speeders caught per road in E district? Clarification Requested: Would you be happy with those sites identified as having met the criteria for enforcement at 30mph by the NIRSP in the new district of ‘Armagh City, Banbridge and Craigavon’? I have provided a list below. Please let me know how you wish to proceed. Madden Road, Tandragee Monaghan road, Middletown village, Armagh Kilmore Road, Richhill, Armagh Whinny Hill, Gilford Donaghcloney Road, Blackskull Hilltown Road, Rathfriland Banbridge Road, Waringstown Main Street, Loughgall Scarva Road, Banbridge Banbridge Road, Kinallen Kernan Road, Portadown A3 Monaghan Road Armagh Road, Portadown Portadown Road, Tandragee Clarification Received: Yes I would be happy with those figures. -

Ulster Gardens Scheme 2016 Open Gardens

Ulster Gardens Scheme 2016 Open Gardens Admission £3 All funds raised help support National Trust gardens in Northern Ireland May 2016 Saturday 14 and Sunday 15 May 2–5pm Mr Richard and Mrs Beverley Brittain 31b Carrowdore Road, Greyabbey, BT22 2LU As seen on BBC Northern Ireland's Greatest Gardens, this three acre garden is in a reclaimed quarry with natural woodland, ponds and small bridges. Meandering moss paths lead to different areas, including a small vegetable garden and a fruit garden. There is a Summer House perched on the top of the quarry, albeit painted blue! Many benches and viewing areas are located within the garden. Planting consists mainly of foxgloves, primulas and camellias, plus a mixture of native and ornamental trees. Diarmuid Gavin described the moss garden as, 'enchanting' and Helen Dillon described the garden as, 'absolutely heavenly'. Partially suitable for wheelchairs. Children must be supervised at all times. Location: From A20 Newtownards to Portaferry Road turn left into Mount Stewart Road towards Ballywalter. After approximately 2 miles turn right into Carrowdore Road towards Greyabbey. The garden is about one mile on the left hand side. Plant Stall / Teas June 2016 Saturday 11 and Sunday 12 June 2–5pm Mr Mervyn D N Singer ‘Gremford’, 59 Mullafernaghan Road, Dromore, BT25 1JZ A country garden of more than two acres developed over a 25 year period from a green field site. Mixed planting provides all year round colour. Highlights include the Summer House with a stream and pond, secluded area with gazebo and scree planting. Partially suitable for wheelchairs. -

Register of Employers 2021

REGISTER OF EMPLOYERS A Register of Concerns in which people are employed In accordance with Article 47 of the Fair Employment and Treatment (Northern Ireland) Order 1998 The Equality Commission for Northern Ireland Equality House 7-9 Shaftesbury Square Belfast BT2 7DP Tel: (02890) 500 600 E-mail: [email protected] August 2021 _______________________________________REGISTRATION The Register Under Article 47 of the Fair Employment and Treatment (Northern Ireland) Order 1998 the Commission has a duty to keep a Register of those concerns employing more than 10 people in Northern Ireland and to make the information contained in the Register available for inspection by members of the public. The Register is available for use by the public in the Commission’s office. Under the legislation, public authorities as specified by the Office of the First Minister and the Deputy First Minister are automatically treated as registered with the Commission. All other employers have a duty to register if they have more than 10 employees working 16 hours or more per week. Employers who meet the conditions for registration are given one month in which to apply for registration. This month begins from the end of the week in which the concern employed more than 10 employees in Northern Ireland. It is a criminal offence for such an employer not to apply for registration within this period. Persons who become employers in relation to a registered concern are also under a legal duty to apply to have their name and address entered on the Register within one month of becoming such an employer. -

EONI-REP-223 - Streets - Streets Allocated to a Polling Station by Area Local Council Elections: 02/05/2019

EONI-REP-223 - Streets - Streets allocated to a Polling Station by Area Local Council Elections: 02/05/2019 LOCAL COUNCIL: ARMAGH, BANBRIDGE AND CRAIGAVON DEA: ARMAGH ST PETER'S PRIMARY SCHOOL, COLLEGELANDS, 90 COLLEGELANDS ROAD, CHARLEMONT, DUNGANNON, BT71 6SW BALLOT BOX 1/AR TOTAL ELECTORATE 810 WARD STREET POSTCODE N08000207 AGHINLIG COTTAGES, AGHINLIG, DUNGANNON BT71 6TD N08000207 AGHINLIG PARK, AGHINLIG, DUNGANNON BT71 6TE N08000207 AGHINLIG ROAD, AGHINLIG, DUNGANNON BT71 6SR N08000207 AGHINLIG ROAD, AGHINLIG, DUNGANNON BT71 6SP N08000207 ANNAHAGH ROAD, KILMORE, DUNGANNON BT71 7JE N08000207 ARMAGH ROAD, CORR AND DUNAVALLY, DUNGANNON BT71 7HY N08000207 ARMAGH ROAD, KEENAGHAN, DUNGANNON BT71 7HZ N08000207 ARMAGH ROAD, DRUMARN, DUNGANNON BT71 7HZ N08000207 ARMAGH ROAD, KILMORE, DUNGANNON BT71 7JA N08000207 CANARY ROAD, DERRYSCOLLOP, DUNGANNON BT71 6SU N08000207 CANARY ROAD, CANARY, DUNGANNON BT71 6SU N08000207 PORTADOWN ROAD, CHARLEMONT BORO, DUNGANNON BT71 7SE N08000207 COLLEGE LANDS ROAD, KISHABOY, DUNGANNON BT71 6SN N08000207 CHURCHVIEW, CHARLEMONT, DUNGANNON BT71 7SZ N08000207 DERRYGALLY ROAD, DERRYCAW, DUNGANNON BT71 6LZ N08000207 GARRISON PLACE, CHARLEMONT, DUNGANNON BT71 7SA N08000207 MAIN STREET, CHARLEMONT, MOY BT71 7SF N08000207 COLLEGE LANDS ROAD, CHARLEMONT BORO, MOY BT71 7SE N08000207 COLLEGE LANDS ROAD, KEENAGHAN, MOY BT71 6SN N08000207 COLLEGE LANDS ROAD, AGHINLIG, MOY BT71 6SW N08000207 CORRIGAN HILL ROAD, KEENAGHAN, DUNGANNON BT71 6SL N08000207 DERRYCAW ROAD, CANARY, DUNGANNON BT71 6SX N08000207 DERRYCAW ROAD, CANARY, -

Rathcairn Brochure

RATHCAIRN HOUSE Blackskull Road, Dromore, Co. Down A Magnificent Country House situated on circa 10 acres CRL Gold Award Winner for Excellence “Best Individual Dwelling” ‘Craftsmanship from a bygone era...’ RATHCAIRN HOUSE Blackskull Road, Dromore, Co. Down ‘Quality, Grandeur and Luxury abound...’ VISION To create a Country House of grand proportions on this unique and mature elevated site, while incorporating the historical Rath and maximising extensive southerly views. PHILOSOPHY At Thompson Developments our philosophy is quite simple... “Build each house as if it were your own and in this respect that’s why we believe that quality comes as standard; quality in design; quality in the materials we use and quality in the craftsmen we employ” Rathcairn House, with it’s uncompromising attention to detail and generous proportions, is the embodiment of all our objectives. GENERAL SPECIFICATION Structure drinking water to all cold water taps. cutstring staircase, with painted • The property is constructed with • Multi zoned underfloor heating spindles and solid oak handrail. a solid concrete floor throughout to all floors with digital • Period style front and rear doors and a combination of old style thermostatic controls. with ornate glazed side panels and 18” and 24” cavity walls, faced • Energy saving features includes fanlights. with locally quarried stone, insulation boards fitted below the • Feature exposed oak trusses in extensive use of granite, traditional level of the ground floor slab, kitchen and library. lime mortar wet-dash render with ground floor and first floor screed; • Glazed atrium over kitchen. reclaimed Belfast brick detailing. full filled cavity and high density • Traditional wet plastered walls • Extensive use of granite inc. -

Information of Service Men and Women Death While on Operations

Army Secretariat Army Headquarters IDL 24 Blenheim Building Marlborough Lines Andover Hampshire, SP11 8HJ United Kingdom Ref: Army Sec/06/06/09633/75948 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.army.mod.uk xxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx 23 November 2015 Dear xxxxxxxxxx,, Thank you for your email of 1 November requesting the following information: - A list of deaths of servicemen/women of the British Army while on 'Op Banner' (Northern Ireland), where the death was due to terrorism or otherwise. I would, ideally, like the information in a spreadsheet. With the following information, ‘Service Number, Rank, First Names, Last Name, Unit, Age, Date of Death, Place of Death, and how died. - A list of deaths of servicemen/women of the British Army while on recent operations in Iraq. I would, ideally, like the information in a spreadsheet. With the following information, ‘Service Number, Rank, First Names, Last Name, Unit, Age, Date of Death, Place of Death, and how died. - A list of deaths of servicemen/women of the British Army while on recent operations in Afghanistan. I would, ideally, like the information in a spreadsheet. With the following information, ‘Service Number, Rank, First Names, Last Name, Unit, Age, Date of Death, Place of Death, and how died. I am treating your correspondence as a request for information under the Freedom of Information Act 2000. A search for the information has now been completed within the Ministry of Defence, and I can confirm that all information in scope of your request is held. The information you have requested for a list of deaths of servicemen and women in Northern Ireland on Op Banner is available in the attached spreadsheet. -

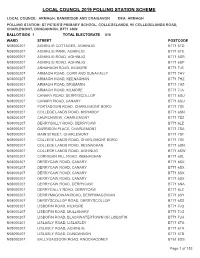

Local Council 2019 Polling Station Scheme

LOCAL COUNCIL 2019 POLLING STATION SCHEME LOCAL COUNCIL: ARMAGH, BANBRIDGE AND CRAIGAVON DEA: ARMAGH POLLING STATION: ST PETER'S PRIMARY SCHOOL, COLLEGELANDS, 90 COLLEGELANDS ROAD, CHARLEMONT, DUNGANNON, BT71 6SW BALLOT BOX 1 TOTAL ELECTORATE 816 WARD STREET POSTCODE N08000207AGHINLIG COTTAGES, AGHINLIG BT71 6TD N08000207AGHINLIG PARK, AGHINLIG BT71 6TE N08000207AGHINLIG ROAD, AGHINLIG BT71 6SR N08000207AGHINLIG ROAD, AGHINLIG BT71 6SP N08000207ANNAHAGH ROAD, KILMORE BT71 7JE N08000207ARMAGH ROAD, CORR AND DUNAVALLY BT71 7HY N08000207ARMAGH ROAD, KEENAGHAN BT71 7HZ N08000207ARMAGH ROAD, DRUMARN BT71 7HZ N08000207ARMAGH ROAD, KILMORE BT71 7JA N08000207CANARY ROAD, DERRYSCOLLOP BT71 6SU N08000207CANARY ROAD, CANARY BT71 6SU N08000207PORTADOWN ROAD, CHARLEMONT BORO BT71 7SE N08000207COLLEGE LANDS ROAD, KISHABOY BT71 6SN N08000207CHURCHVIEW, CHARLEMONT BT71 7SZ N08000207DERRYGALLY ROAD, DERRYCAW BT71 6LZ N08000207GARRISON PLACE, CHARLEMONT BT71 7SA N08000207MAIN STREET, CHARLEMONT BT71 7SF N08000207COLLEGE LANDS ROAD, CHARLEMONT BORO BT71 7SE N08000207COLLEGE LANDS ROAD, KEENAGHAN BT71 6SN N08000207COLLEGE LANDS ROAD, AGHINLIG BT71 6SW N08000207CORRIGAN HILL ROAD, KEENAGHAN BT71 6SL N08000207DERRYCAW ROAD, CANARY BT71 6SX N08000207DERRYCAW ROAD, CANARY BT71 6SX N08000207DERRYCAW ROAD, CANARY BT71 6SX N08000207DERRYCAW ROAD, CANARY BT71 6SX N08000207DERRYCAW ROAD, DERRYCAW BT71 6NA N08000207DERRYGALLY ROAD, DERRYCAW BT71 6LZ N08000207DERRYMAGOWAN ROAD, DERRYMAGOWAN BT71 6SY N08000207DERRYSCOLLOP ROAD, DERRYSCOLLOP BT71 6SS N08000207LISBOFIN -

Directory 2020 Stations of Ordained Ministers and Probationers JUNE 2020

METHODIST CHURCH IN IRELAND Directory: A Directory 2020 Stations of Ordained Ministers and Probationers JUNE 2020 SOUTHERN DISTRICT A: Stations of Ministers June 2020 (pp 1-5) District Superintendent: Andrew J Dougherty B: Mission Partners (p 5) 1. Dublin South City (Centenary Leeson Park, Dublin Korean Church and Rathgar), Andrew G Kingston, Yongnam Park, __________ C: Hospital Chaplains (pp 6-7) Retired Ministers: John Parkin, Vanessa G Wyse Jackson. D: University Chaplains (p 8) 2. Dublin Central Mission (Abbey Street), Laurence A M Graham, Tawanda Sungai (Blanchardstown and Lucan) E: Ordained Ministers and Probationers (pp 8-19) 3. Dublin North, Ivor N Owens. F: Ministers’ Widows and Widowers (pp 20-21) 4. Dublin South (Dundrum), Stephen R Taylor. WESLEY COLLEGE, Nigel D Mackey, Chaplain. G: Circuit Lay Workers (pp 21-22) Julian I Hamilton works as part-time Chaplain to Trinity College, Dublin. 5. Dublin, Sandymount Christ Church (United Presbyterian and Methodist), H: Local Preachers (pp 23-27) Katherine P Meyer (Presbyterian Minister). The Superintendent is Laurence A M Graham. I: Lay Officers of Boards etc (pp 27-29) 6. South East Leinster, David H Nixon, Mark S Forsyth, Katherine M Kehoe. J: Church Departments and Officers (pp 29-30) (The Superintendent of Urban Junction is Andrew J Dougherty) SUPERINTENDENT OF THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT: Andrew J Dougherty. Retired Ministers: R Donaldson Rodgers, Desmond C Bain, Paul Kingston (C), Eric Duncan, E Rosemary Lindsay. 7. Kilkenny and Carlow, Susan Gallagher, who works under the direction of Andrew R Robinson who is Superintendent of the Circuit 8. Waterford, Sahr J Yambasu. 9. -

Planning Applications Decisions Issued

Planning Applications Decisions Issued From: 01/10/2017 To: 31/10/2017 No. of Applications: 100 Reference Number Applicant Name & Address Location Proposal Decision Date Time to Decision Process Issued (Working Days) LA05/2015/0588/O I Lappin 24 Comber Road, Approx 30m NE of 67 2 storey dwelling Permission 04/10/2017 498 Killyleagh Beanstown Road Lisburn Refused LA05/2016/0063/F M E Crowe 41a Quarterlands Site 2 Proposed amendments to Permission 26/10/2017 447 Road adjacent to Trench House permission S/2011/0454/ Granted Drumbeg 48 Drumbo Road F for a dwelling house, Lisburn Drumbo garage, ancillary site BT27 5TN BT27 5TX works and access (Amended plans received). LA05/2016/0064/F M E Crowe 41a Quarterlands Site 1 Proposed amendments to Permission 27/10/2017 448 Road adjacent to Trench House permission S/2010/0411/ Granted Drumbeg 48 Drumbo Road F for a dwelling house, Lisburn Drumbo garage, ancillary works BT27 5TN BT27 5TX and access (Amended plans submitted) LA05/2016/0100/F David Mc Comb David 50A Edentrillick Road Proposed vehicular Permission 06/10/2017 425 50A Edentrillick Road Hillsborough access in substitution of Granted Hillsborough Co Down that approved under S/ BT26 6PG BT26 6PG 2005/0850 to include feature piers and gates and associated visibility splays. (Amended Proposal and drawings). Page 1 of 27 Planning Applications Decisions Issued From: 01/10/2017 To: 31/10/2017 No. of Applications: 100 Reference Number Applicant Name & Address Location Proposal Decision Date Time to Decision Process Issued (Working Days) LA05/2016/0172/O -

Writ the Journal of the Law Society of Northern Ireland ISSUE 200 Oct / Dec 2009

THE WriT THE journal of THE laW SociETy of norTHErn irEland iSSuE 200 ocT / dEc 2009 THiS MONTH The official opening of Law Society House Journal of the LSNI October / December 2009 03 INDEX OCT / dEc 2009 McClure PUBLISHERS Watters The Law Society of Northern Ireland 96 Victoria Street THE BELFAST BT1 3GN WriT Tel: 028 9023 1614 THE journal of THE laW SociETy of norTHErn irEland iSSuE 199 SEpTEmbEr 2009 Fax: 028 9023 2606 E-mail: [email protected] Specialist Services Website: www.lawsoc-ni.org EdItoR Alan Hunter for Solicitors [email protected] dEPUtY EdItoRS Heather Semple [email protected] Peter O’Brien [email protected] Supporting your legal expertise AdvERtISIng MAnAgER Karen Irwin Responding to your needs THiS monTH [email protected] The official opening of Law dESIgn Society House Walker Communications Ltd www.walkercommunications.co.uk At FGS McClure Watters, our taxation services are designed to offer you and your clients optimum tax-efficient solutions. dISCLAIMER The Law Society of Northern Ireland accepts no responsibility for the accuracy of contributed articles 04 cover Story: or statements appearing in this magazine and any views or opinions expressed are not necessarily those Our Services include: of the Law Society’s Council, save where otherwise The official opening of indicated. No responsibility for loss or distress Inheritance Tax VAT occasioned to any person acting or refraining from law Society House acting as a result of the material in this publication can be accepted by the authors, contributors, » Gift & Inheritance Tax Planning & Returns » VAT Planning editor or publishers.