The Ride to York by William Harrison Ainsworth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

© Georgina Green ~ Epping Forest Though the Ages

© Georgina Green ~ Epping Forest though the Ages Epping Forest Preface On 6th May 1882 Queen Victoria visited High Beach where she declared through the Ages "it gives me the greatest satisfaction to dedicate this beautiful Forest to the use and enjoyment of my people for all time" . This royal visit was greeted with great enthusiasm by the thousands of people who came to see their by Queen when she passed by, as their forefathers had done for other sovereigns down through the ages . Georgina Green My purpose in writing this little book is to tell how the ordinary people have used Epping Fo rest in the past, but came to enjoy it only in more recent times. I hope to give the reader a glimpse of what life was like for those who have lived here throughout the ages and how, by using the Forest, they have physically changed it over the centuries. The Romans, Saxons and Normans have each played their part, while the Forest we know today is one of the few surviving examples of Medieval woodland management. The Tudor monarchs and their courtiers frequently visited the Forest, wh ile in the 18th century the grandeur of Wanstead House attracted sight-seers from far and wide. The common people, meanwhile, were mostly poor farm labourers who were glad of the free produce they could obtain from the Forest. None of the Forest ponds are natural . some of them having been made accidentally when sand and gravel were extracted . while others were made by Man for a variety of reasons. -

Robbery TRUE CRIME MAG COMPLETE Template For

CASEBOOK: CLASSIC CRIME ISSUE 4 APRIL 2016 Read the article by Nich olas Booth! www.whitechapelsociety.com page 1 www.whitechapelsociety.com CASEBOOK: CLASSIC CRIME Planes, Trains & Capital Gains A LEGENDARY LEAP by Joe Chetcuti PEACE BY PIECE By Ben Johnson THE FATAL SHOOTING OF PC COCK By Angela Buckley STAND AND DELIVER --- DICK TURPIN AND THE ESSEX BOYS By Edward Stow THE THIEVES OF THREADNEEDLE STREET By Nicholas Booth FOR THE GGREATERREATER GOOD --- THE BEZDANY RAID By William Donarski BOOK REVIEWS KRAYOLOGY Reviewed by Mickey Mayhew THE THIEVES OF THREADNEEDTHREADNEEDLELE STREET Reviewed by Ruby Vitorino www.whitechapelsociety.com page 2 www.whitechapelsociety.com The JournalEDITORIALEDITORIAL of The Whitechapel BYBY BENBEN Society. JOHNSONJOHNSON August 2009 n my student days, I was the victim of a burglary; although, given the area of Sheffield in which my tiny one-bedroom flat was situated, I was probably lucky to only experience this on one occasion (Seriously, just Google “axe attack Sheffield” and you will be able to see my old neighbourhood in all its glory!). I Being the victim of such a crime is a terrible thing. It becomes impossible to relax in your own home, and the sense of anger and anxiety which follow are something which can seriously play on your mind for months to follow. You may then think it is strange that I spent a year of my life writing the biography of a famous Sheffield burglar, exploring his antics and dragging his cowardly crimes back into the limelight after a century of almost obscurity. The rogue in question was Charles Frederick Peace, a master of cat burglary and cunning disguise, and a man whose life was entirely deserving of being immortalised. -

Fight Record Dick Turpin (Leamington)

© www.boxinghistory.org.uk - all rights reserved This page has been brought to you by www.boxinghistory.org.uk Click on the image above to visit our site Dick Turpin (Leamington) Active: 1937-1950 Weight classes fought in: Recorded fights: 105 contests (won: 79 lost: 20 drew: 6) Fight Record 1937 Sep 27 Eric Lloyd (Rugby) WRSF4(6) Co-op Hall, Rugby Source: Boxing Weekly Record 06/10/1937 page 19 Oct 4 Trevor Burt (Ogmore Vale) LKO3(6) Coventry Source: Vic Hardwicke (Boxing Historian) Oct 16 Eddie Harris (Worcester) WRSF6(6) Public Hall, Evesham Source: Boxing 20/10/1937 page 17 Nov 1 Frank Guest (Birmingham) WPTS(4) Embassy Rink, Sparkbrook Source: Boxing Weekly Record 10/11/1937 page 20 Promoter: Ted Salmon Nov 15 Trevor Burt (Ogmore Vale) WPTS(6) Drill Hall, Coventry Source: Boxing 17/11/1937 page 12 Nov 20 Phil Proctor (Broadway) WRSF2(6) Public Hall, Evesham Source: Boxing 24/11/1937 page 19 Dec 13 Frank Guest (Birmingham) WKO6(6) Embassy Rink, Sparkbrook Source: Boxing 15/12/1937 page 12 Promoter: Ted Salmon Dec 18 Ray Chadwick (Leicester) WKO4(6) Public Hall, Evesham Source: Boxing 22/12/1937 page 20 1938 Feb 19 Bill Blything (Wolverhampton) WRTD4(10) Public Hall, Evesham Source: Boxing 23/02/1938 page 19 Feb 21 Walter Rankin (Glasgow) WPTS(8) Nuneaton Source: Graham Grant (Boxing Historian) Mar 7 Bob Hartley (Billingborough) DRAW(8) Co-op Hall, Rugby Source: Vic Hardwicke (Boxing Historian) Mar 19 Frankie Smith (Belfast) WKO4(8) Public Hall, Evesham Source: Boxing 23/03/1938 page 18 Mar 28 Trevor Burt (Ogmore Vale) WPTS(8) Drill Hall, Coventry Source: Boxing 30/03/1938 pages 11 and 12 May 23 Sid Fitzhugh (Northampton) WPTS(8) Northampton Source: Boxing 25/05/1938 page 11 Jun 11 Rex Whitney (Wellingborough) LPTS(10) West Haddon Source: Vic Hardwicke (Boxing Historian) Aug 15 Johnny Clarke (Highgate) WPTS(10) Kingsholm Rugby Ground, Gloucester Source: Boxing 17/08/1938 page 11 Promoter: Capt. -

Dick Turpin Age Related Historical Vocabulary Argument a Disagreement As to What Has Happened

Selby Community Primary School Subject Knowledge Bank History Year 2 Focus Local historical people/events Dick Turpin Age related historical vocabulary Argument A disagreement as to what has happened. Significance Something important. Contribution Something that someone has helped with. Achievements Something good that happened. Plague A disease that killed many people carried Primary source Gives you information about the past that by fleas on rats. of evidence was from the time it happened. Secondary Gives you information about the past that Disease A serious illness. source of has been created after it has happened evidence with the help of primary sources of Research Investigate and study information to evidence. establish conclusions. Locality Near where you live. Chronological Putting things in order depending on when they happen. Events Something that happens. Identity Find out. Black Death Thomas Lawrence WW1 Amy Johnson 1347-1350 1888-1935 1914-1918 1903-1941 Dick Turpin Queen Elizabeth 11 1705-1739 Born 1926- Key Knowledge Dick Turpin was born in 1705 and became a butcher. He began stealing when he joined a criminal gang in Essex. He was a cattle thief and his stealing progressed into burglary where he committed terrible crimes. Together with Tom King he became a much feared highwayman robbing stage coaches during the night. Turpin killed his friend Tom King by accident in a robbery that went wrong. He also murdered a servant called Tom Morris. There was a huge reward for the capture of Dick Turpin and so he fled to Yorkshire where he changed his name to John Palmer. Turpin was arrested for shooting a chicken and threatening to kill his landlord. -

Beyond the St Marylebone Workhouse: Songs of London Life Gone By

Beyond the St Marylebone Workhouse: songs of London life gone by A music resource for schools and SEN settings by Hazel Askew Created with support from The National Lottery Heritage Fund as part of the St Marylebone Changing Lives project. The English Folk Dance and Song Society The English Folk Dance and Song Society (EFDSS) is the national development organisation for folk music, dance and related arts, based at Cecil Sharp House, a dedicated folk arts centre and music venue, in Camden, North London. EFDSS creates and delivers creative learning projects for children, young people, adults and families at Cecil Sharp House, across London and around the country; often in partnership with other organisations. Learning programmes draw on the diverse and vibrant traditional folk arts of Britain and beyond, focusing on song, music, dance and related art forms such as storytelling, drama, and arts and crafts. www.efdss.org/education Vaughan Williams Memorial Library Cecil Sharp House is also home to EFDSS’s Vaughan Williams Memorial Library (VWML), England’s national folk music and dance archive, which provides free online access to over 200,000 searchable folk manuscripts and other materials. www.vwml.org/ This resource was made in collaboration with St Marylebone Parish Church with support from The National Lottery Heritage Fund as part of the St Marylebone Changing Lives project. Produced by the English Folk Dance and Song Society (EFDSS), 2021 Written by Hazel Askew Songs compiled/arranged by Hazel Askew Recordings by Hazel Askew Edited by Esbjorn Wettermark Photos and illustrations in common domain or used with permission Photo of Hazel Askew by Elly Lucas Copyright © English Folk Dance and Song Society This resource, with the accompanying audio tracks, is freely downloadable from the EFDSS Resource Bank: www.efdss.org/resourcebank Permission is granted to make copies of this material for non-commercial educational purposes. -

English Legal Histories

English Legal Histories Ian Ward HART PUBLISHING Bloomsbury Publishing Plc Kemp House , Chawley Park, Cumnor Hill, Oxford , OX2 9PH , UK 1385 Broadway, New York, NY 10018, USA HART PUBLISHING, the Hart/Stag logo, BLOOMSBURY and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published in Great Britain 2019 Copyright © Ian Ward , 2019 Ian Ward has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identifi ed as Author of this work. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. While every care has been taken to ensure the accuracy of this work, no responsibility for loss or damage occasioned to any person acting or refraining from action as a result of any statement in it can be accepted by the authors, editors or publishers. All UK Government legislation and other public sector information used in the work is Crown Copyright © . All House of Lords and House of Commons information used in the work is Parliamentary Copyright © . This information is reused under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 ( http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/ open-government-licence/version/3 ) except where otherwise stated. All Eur-lex material used in the work is © European Union, http://eur-lex.europa.eu/ , 1998–2019. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Ward, Ian, author. -

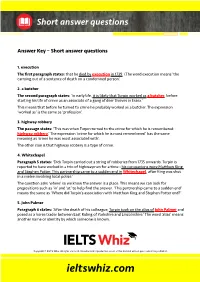

Answer Questions

Short answer questions Answer Key – Short answer questions 1. execution The first paragraph states: that he died by execution in 1739. (The word execution means ‘the carrying out of a sentence of death on a condemned person’. 2. a butcher The second paragraph states: ‘In early life, it is likely that Turpin worked as a butcher, before starting his life of crime as an associate of a gang of deer thieves in Essex.’ This means that before he turned to crime he probably worked as a butcher. The expression ‘worked as’ is the same as ‘profession’. 3. highway robbery The passage states: ‘This was when Turpin turned to the crime for which he is remembered: highway robbery.’ The expression ‘crime for which he is most remembered’ has the same meaning as ‘crime he was most associated with’. The other clue is that highway robbery is a type of crime. 4. Whitechapel Paragraph 5 states: ‘Dick Turpin carried out a string of robberies from 1735 onwards. Turpin is reported to have worked in a trio of highwaymen for a time - his companions were Matthew King and Stephen Potter. This partnership came to a sudden end in Whitechapel, after King was shot in a melee involving local police.’ The question asks ‘where’ so we know the answer is a place. This means we can look for prepositions such as ‘in’ and ‘at’ to help find the answer. ‘This partnership came to a sudden end’ means the same as ‘Where did Turpin’s association with Matthew King and Stephen Potter end?’ 5. John Palmer Paragraph 6 states: ‘After the death of his colleague, Turpin took on the alias of John Palmer and posed as a horse trader between East Riding of Yorkshire and Lincolnshire.’ The word ‘alias’ means another name or identity by which someone is known. -

Turpin's Trail Historical Notes

Turpin’s Trail Historical Notes Dick Turpin was born around 1706 in the village of Hempstead, near Saffron Walden, and was raised in the Bluebell Inn. He was baptised in St Andrew’s church where William Harvey, Chief Physician to Charles I and discoverer of the circulation of the blood, is buried. Not much is known of Turpin’s early years. Local legend has it that he became an apprentice butcher in Thaxted with Ducketts, opposite the parish church and that when he married he moved into a cottage in Stoney Lane which may be the one that is called to this day “Turpin’s Cottage”. After a fairly ordinary childhood and early years, his criminal career started with cattle stealing, and he had to flee into the countryside to avoid being captured. He then associated with other unsavoury characters and formed a gang with whom he proceeded to terrorise the areas in north of London, around Loughton and Epping Forest, robbing anyone that passed their hiding place. His exploits eventually led him to flee to Yorkshire where he lived under an assumed identity, calling himself John Palmer. The King offered a hefty reward of £50 for his capture. Eventually the la caught up with him after his former schoolmaster in Thaxted recognised his handwriting and identified him as Dick Turpin. He was hanged in April 1739 in York. The historic town of Thaxted, which prospered due to the cutlery industry, contains many interesting features. The magnificent Church of St. John the Baptist, Our Lady and St. Lawrence is of cathedral proportions and the exterior contains a large number of interesting gargoyles and other figures. -

A Short History of Highwaymen

Lesson 1: A Short History of Highwaymen Introduction Highwaymen thrived in England in the seventeenth and eighteenth century, becoming legendary and romantic figures. Highwaymen were "as common as crows" from around 1650 to 1800. In an age where travel was already hazardous due to the lack of decent roads, no one rode alone without fear of being robbed, and people often joined company or hired escorts. Travellers often wrote their wills before they travelled. Lies, Exaggeration and Truth The legend of the highwayman is that of a gentleman. High or low born, the legendary highwayman dressed well (with a ‘kerchief’ over his face), was well-mannered, and used threats rather than violence. "Stand and Deliver" and "Your money or your life," were his greetings. Although there were some well-born and well-mannered highwaymen, they were far outnumbered by those who practiced their trade with brutality. Violence was very common. When Tom Wilmot, a notorious highwayman, had difficulty removing a woman's ring, he cut off her finger, Highwaymen's Haunts The four main roads to London were infamous for their criminal activity. On the Great Western Road, Hounslow Heath was notorious for its highwaymen. Robbers on the Great North Road included Dick Turpin. The Dover Road had two infamous spots, Gad's Hill and Shooter's Hill. And John Cotinton, aka "Mulled Sack," stole 4,000 pounds from an army wagon on the Oxford Road. Wimbledon Common, Blackheath, Barnes Common, Bagshort Heath; all were frequented by robbers. Salisbury Plain was also noted for its highwaymen. The Most Famous Highwayman: Dick Turpin Born in Essex in 1705, Turpin was taught to read and write and became an apprentice to a butcher. -

A Walthamstow Murder

A Walthamstow Murder Walthamstow in the 21st century Today, Walthamstow is a densely populated outer London Borough with a diverse multi cultural community. It is located in an area where the land rises steadily up from the River Lea marshes to Epping Forest. Today, both of these areas are playgrounds for Londoners. The marshes are part of the Lea Valley Park and Epping Forest is managed by the City of London. It has a well developed transport system with easy access to motorways, overground and underground railways and a central bus hub. Our local geographical knowledge of the Borough is largely governed by our GPS devices. We know that, on one side, it is bounded by the River Lea and on the other by Epping Forest. But, because it is largely covered by buildings and concrete and because we travel everywhere by car or public transport, generally, we are not aware of the topography of the surrounding terrain . Walthamstow in the 18th century For us in the 21st century, it is very difficult to imagine what Walthamstow was like in 1750. Then, it was a collection of small Essex hamlets at Hale End, Wood Street, Chapel End, Church End and Higham Hill. These were linked by a network of unmade roads along which were scattered dwellings. In the entire Parish, there were less than two thousand people who lived in the three hundred dwellings that made up the Parish of St Mary, Walthamstow. Transport Two main highways ran from London across the River Lea by bridge and ferry. These were the road that went from Hackney across the River Lea toll bridge to Epping Forest via Phipps Cross (Whipps Cross) to Wanstead. -

British Cities

Министерство образования и науки Российской Федерации Федеральное государственное бюджетное образовательное учреждение высшего профессионального образования «Московский педагогический государственный университет» O. Kolykhalova, K. Makhmuryan BRITISH CITIES Учебное пособие для обучающихся в бакалавриате по направлению подготовки «Педагогическое образование» Рекомендовано УМО по образованию в области подготовки педагогических кадров в качестве учебного пособия для студентов высших учебных заведений, обучающихся по направлению 050100.62 «Педагогическое образование» МПГУ Москва • 2014 УДК 811.111 СОДЕРЖАНИЕ ББК 81.432.1я73 К619 PART 1 OXFORD AND CAMBRIDGE . 5 Oxford . 5 All Souls College . 8 Рецензенты: Е. Р. Ватсон, кандидат филологических наук, доцент The World of Alice . 12 И. Ш. Алешина, кандидат психологических наук, доцент The Dean’s Daughter . 13 Tell us a story . 15 Alice’s Oxford . 16 Cambridge . 18 The Hidden Head . 21 PART 2 SHAKESPEARE COUNTRY . 24 Колыхалова, Ольга Алексеевна. Stratford-upon-Avon . 24 К619 Вritish cities : Учебное пособие для обучающихся в бака- лавриате по направлению подготовки «Педагогическое обра- Coventry . 27 зование» / O. Kolykhalova, K. Makhmuryan. – Москва : МПГУ, Birmingham . 30 2014. – 84 с. : ил. ISBN 978-5-4263-0148-1 PART 3 Учебное пособие «BRITISH CITIES» для обучающихся в бакалав- CANTERBURY AND THE SOUTHEAST . 34 риате по направлению подготовки «Педагогическое образование» ста- Charles Dickens country . 34 вит своей целью развитие у студентов навыков устной речи и предпо- лагает усвоение большого объема лексики по теме города Британии. Canterbury . 38 УДК 811.111 PART 4 ББК 81.432.1я73 BRIGHTON AND THE DOWNS . 44 ISBN 978-5-4263-0143-6 © МПГУ, 2014 Raffi sh Brighton . 44 © Колыхалова О. А., текст, 2014 © Махмурян К. С., текст, 2014 PART 5 PART 1 THE ENGLISH GARDEN. -

Dick Turpin (1705-1739), the Notorious Highwayman, Made His Mark in the Area During His Life of Crime

Epping Forest is an area of ancient woodland in south-east England, straddling the border between north-east Greater London and Essex. Formed in approximately 8000 BC after the last ice age, it covers nearly 6,000 acres (24 km²)[1] and contains areas of grassland, heath, rivers, bogs and ponds. Stretching between Forest Gate in the south and Epping in the north, Epping Forest is approximately 18 km long in the north-south direction, but no more than 4 km from east to west at its widest point, and in most places considerably narrower. The forest lies on a ridge between the valleys of the rivers Lea and Roding; its elevation and thin gravelly soil - the result of glaciation - historically made it unsuitable for agriculture. Embankments of two Iron Age camps - Loughton Camp and Ambresbury Banks - can be found hidden in the woodland. It gives its name to the Epping Forest local government district. Dick Turpin (1705-1739), the notorious highwayman, made his mark in the area during his life of crime. In about 1734, the Widow Shelley, living in a farm on Traps Hill, was supposedly roasted over her own fire by Turpin until she confessed to where her money was hidden. In fact, his last spell of 'going straight' before he became a professional thief appears to have been in Buckhurst Hill, where between 1733-4 he was a butcher. The area was no doubt convenient for deer-poaching, another of his 'trades'. Fear of his ruthless style of burglary led householders in Loughton to build 'Turpin traps', heavy wooden flaps let down over the top of the stairs and jammed in place with a pole against the upstairs ceiling.