Dr John Ellor Taylor: Guide, Philosopher and Friend

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Music-Making in a Joyous Sense”: Democratization, Modernity, and Community at Benjamin Britten's Aldeburgh Festival of Music and the Arts

“Music-making in a Joyous Sense”: Democratization, Modernity, and Community at Benjamin Britten's Aldeburgh Festival of Music and the Arts Daniel Hautzinger Candidate for Senior Honors in History Oberlin College Thesis Advisor: Annemarie Sammartino Spring 2016 Hautzinger ii Table of Contents 1. Introduction 1 2. Historiography and the Origin of the Festival 9 a. Historiography 9 b. The Origin of the Festival 14 3. The Democratization of Music 19 4. Technology, Modernity, and Their Dangers 31 5. The Festival as Community 39 6. Conclusion 53 7. Bibliography 57 a. Primary Sources 57 b. Secondary Sources 58 Hautzinger iii Acknowledgements This thesis would never have come together without the help and support of several people. First, endless gratitude to Annemarie Sammartino. Her incredible intellect, voracious curiosity, outstanding ability for drawing together disparate strands, and unceasing drive to learn more and know more have been an inspiring example over the past four years. This thesis owes much of its existence to her and her comments, recommendations, edits, and support. Thank you also to Ellen Wurtzel for guiding me through my first large-scale research paper in my third year at Oberlin, and for encouraging me to pursue honors. Shelley Lee has been an invaluable resource and advisor in the daunting process of putting together a fifty-some page research paper, while my fellow History honors candidates have been supportive, helpful in their advice, and great to commiserate with. Thank you to Steven Plank and everyone else who has listened to me discuss Britten and the Aldeburgh Festival and kindly offered suggestions. -

Charles Darwin: a Companion

CHARLES DARWIN: A COMPANION Charles Darwin aged 59. Reproduction of a photograph by Julia Margaret Cameron, original 13 x 10 inches, taken at Dumbola Lodge, Freshwater, Isle of Wight in July 1869. The original print is signed and authenticated by Mrs Cameron and also signed by Darwin. It bears Colnaghi's blind embossed registration. [page 3] CHARLES DARWIN A Companion by R. B. FREEMAN Department of Zoology University College London DAWSON [page 4] First published in 1978 © R. B. Freeman 1978 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the permission of the publisher: Wm Dawson & Sons Ltd, Cannon House Folkestone, Kent, England Archon Books, The Shoe String Press, Inc 995 Sherman Avenue, Hamden, Connecticut 06514 USA British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Freeman, Richard Broke. Charles Darwin. 1. Darwin, Charles – Dictionaries, indexes, etc. 575′. 0092′4 QH31. D2 ISBN 0–7129–0901–X Archon ISBN 0–208–01739–9 LC 78–40928 Filmset in 11/12 pt Bembo Printed and bound in Great Britain by W & J Mackay Limited, Chatham [page 5] CONTENTS List of Illustrations 6 Introduction 7 Acknowledgements 10 Abbreviations 11 Text 17–309 [page 6] LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Charles Darwin aged 59 Frontispiece From a photograph by Julia Margaret Cameron Skeleton Pedigree of Charles Robert Darwin 66 Pedigree to show Charles Robert Darwin's Relationship to his Wife Emma 67 Wedgwood Pedigree of Robert Darwin's Children and Grandchildren 68 Arms and Crest of Robert Waring Darwin 69 Research Notes on Insectivorous Plants 1860 90 Charles Darwin's Full Signature 91 [page 7] INTRODUCTION THIS Companion is about Charles Darwin the man: it is not about evolution by natural selection, nor is it about any other of his theoretical or experimental work. -

See East Anglia... the Coast

46 TRAVEL PROFILE www.greateranglia.co.uk Eastern Daily Press, Friday, July 27, 2012 Eastern Daily Press, Friday, July 27, 2012 www.greateranglia.co.uk TRAVEL PROFILE 47 Pictures: ANTONY KELLY / RSPB / VISIT EAST ANGLIA / EAST ANGLIAN DAILY TIMES 2 FOR 1 OFFERS See East Anglia... The coast Visit www.greateranglia.co.uk/vea and in association with find more than seventy 2 for 1 vouchers to attractions, historic houses, gardens, EVENTS Visit East Anglia and museums, hotels, restaurants, theatres and ■ Sheringham Carnival ■ Aldeburgh Carnival tours throughout the region when you travel July 28-August 5 August 18-20 www.sheringhamcarnival.co.uk www.aldeburghcarnival.com by train with Greater Anglia. In addition to ■ Wells-next-the-Sea Carnival ■ Clacton Airshow July 27-August 5 August 23-24 the website, brochures containing all the www.wellscarnival.co.uk/ www.clactonairshow.com ■ Cromer Carnival ■ Burnham Week offers can also be found at your nearest August 11-17 August 25-September 1 train station or Tourist Information Centre. www.cromercarnival.co.uk/ burnhamweek.org.uk/ ■ Southwold Lifeboat Day ■ Wells-next-the-Sea Pirate Festival August 11 September 7-9 www.visiteastofengland.com www.wellsmaltings.org.uk ■ Clacton Carnival ■ International Talk Like a Pirate Day ■ The Crown Hotel, Wells-next-the-Sea, and ■ Hollywood Indoor Adventure Golf, August 13-19 September 19 The Ship Hotel, Brancaster, Norfolk Great Yarmouth How to make www.clactoncarnival.org/ www.talklikeapirate.com 2 for 1 OFFER Stay one night at any of our 2 for 1 OFFER Two -

Friends Newsletter 1 FOIM Newsletter - Summer 2009

FOIM Newsletter - Summer 2009 Summer 2009 © Colchester and Ipswich Museum Service Ipswich Museums Friends Newsletter 1 FOIM Newsletter - Summer 2009 Contents Editor’s Notes 3 IAA Discounts 3 Chairman’s Message 4 The Friends of the Ipswich Museums Newsletter is published quarterly and Peter Berridge’s Column 5 distributed free to all members. The FOIM AGM Report 7 was set up in 1934 to support the work Friends Events and News 9 and development of the Ipswich Membership Secretary 9 Museums: Ipswich Museum in the High Mansion Guides 10 Street (including Gallery 3 at the Town Webmaster 10 Hall) , Christchurch Mansion and the Visit to Cumbria 11 Wolsey Gallery in Christchurch Park. Since April 2007 the Ipswich Museums New Darwin Letter 13 have been managed as part of the New Constable Portraits 14 Colchester and Ipswich Museum Service. Reserving Judgement 15 Friends continue to provide financial Ipswich’s Wallace Collection 16 support to the Ipswich Museums as well Persian Splendours 17 as acting as volunteers. The Friends run Summer at the Mansion 19 outings, lectures and other events for their A Letter from Bristol 20 members. Ipswich Museum Highlights 22 The Friends provide guided tours of both Colchester Events 23 the Mansion and the Museum, including Other Ipswich Organisations 23 free taster tours of the Mansion on FOIM Council 2009 –2010 24 Wednesday afternoons during British Corporate Members 24 Summer Time. Tours can be booked by contacting the Mansion (01473 433554). FOIM is a member of the British Association of Friends of Museums and Ipswich Arts Association. Cover Illustration: Friends at Tullie House—see visit report on page 11 or Contributions to the Autumn 2009 Amédée Forestier, A Scene from Omar Newsletter should be sent to the editor by Khayyam 3 August (address on back cover). -

Vol53no3 with Accts

Vol 53 No 3 ISSN 1479-0882 May / June 2019 The Wareham (Dorset) which is celebrating ten years of being run by a Trust – see Newsreel p28; photo taken May 2006 The Hucknall (Notts). A new owner is planning to convert it into a four-screen cinema – see Newsreel p24; photo taken May 2008 I owe all members and also Michael Armstrong and his colleagues at the Wymondham a big apology. For the first two issues this year Company limited by guarantee. Reg. No. 04428776. I erroneously printed last year’s programme in the ‘Other Registered address: 59 Harrowdene Gardens, Teddington, TW11 0DJ. Events’ section of the Bulletin. I must have misfiled the current Registered Charity No. 1100702. Directors are marked in list below. programme card and used the old one instead. I have done a suitable penance. The listing on p3 is correct! Thank you all for continuing to send in items for publication. I have been able to use much of the backlog this time. On p32 I have printed Full Membership (UK)..................................................................................£29 some holiday snaps from Ned Williams. I have had these in stock Full Membership (UK under 25s)...............................................................£15 since July 2017, just waiting for a suitable space. I say this simply to Overseas (Europe Standard & World Economy)........................................£37 prove I throw nothing away deliberately – although, as noted above, I Overseas (World Standard).........................................................................£49 Associate Membership (UK & Worldwide).................................................£10 can sometimes do so by accident. Life Membership (UK only).................................£450; aged 65 & over £350 I still have held over a major article from Gavin McGrath on Cinemas Life Membership for Overseas members will be more than this; please contact the membership secretary for details. -

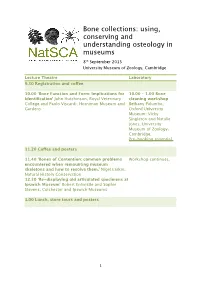

Bone Collections: Using, Conserving and Understanding Osteology in Museums

Bone collections: using, conserving and understanding osteology in museums 8th September 2015 University Museum of Zoology, Cambridge Lecture Theatre Laboratory 9.30 Registration and cofee 10.00 ‘Bone Function and Form: Implications for 10.00 – 1.00 Bone Identification’ John Hutchinson, Royal Veterinary cleaning workshop College and Paolo Viscardi, Horniman Museum and Bethany Palumbo, Gardens Oxford University Museum; Vicky Singleton and Natalie Jones, University Museum of Zoology, Cambridge. Pre-booking essential. 11.20 Cofee and posters 11.40 ‘Bones of Contention: common problems Workshop continues. encountered when remounting museum skeletons and how to resolve them.’ Nigel Larkin, Natural History Conservation 12.30 ‘Re-displaying old articulated specimens at Ipswich Museum’ Robert Entwistle and Sophie Stevens, Colchester and Ipswich Museums 1.00 Lunch, store tours and posters 1 2.00 ‘Skeletal reference collections for 2.00 – 5.00 Bone archaeologists: where zoology and humanities cleaning workshop meet.’ Umberto Albarella, University of Shefeld Bethany Palumbo, 2.50 ‘Bone Idols: Conservation in the public eye.’ Oxford University Jack Ashby, Grant Museum of Zoology, UCL Museum; Vicky 3.15 ‘Conserving a rare Ganges River Dolphin Singleton and Natalie Skeleton: Adhesive removal, consolidation and Jones, University problem solving a challenging re-mounting Museum of Zoology, dilemma’ Emilia Kingham, Grant Museum of Cambridge. Zoology, UCL Pre-booking essential. 3.40 Tea and posters 4.00 'Under the Flesh: preparing skeletons for Workshop continues. your museum.’ Jan Freedman, Plymouth Museums 5.00 End Abstracts 10.00 & 2.00 Bone Cleaning Workshop Pre-booking essential. Bethany Palumbo, Conservator of Life Collections, Oxford University Museum of Natural History Vicky Singleton & Natalie Jones, Conservators, University Museum of Zoology, Cambridge Osteological collections often form a large percentage of Natural History Collections, and many institutions are keen to discover ways of maintaining and preserving these collections. -

Visit Ipswich Museum After Dark!

Visit Ipswich Museum after dark! Torchlight Tours Ipswich Museum Friday 13 th May and Saturday 14 th May You’ve seen it during the day; now see how Ipswich Museum comes to life - at night! Join us for an exciting opportunity on either Friday 13 th or Saturday 14 th of May to explore for yourself what the museum galleries look like by torchlight. Discover new things or perhaps even things you’ve seen before, but in a new way as you journey through the Museum after dark, lead by a one of our friendly guides. This event is sure to be fun for all, so why not bring your friends and family along for a unique look into the past. Laura Hardisty, Marketing Officer at Colchester and Ipswich Museums said, “This is a unique opportunity to see the museum after dark in a completely different light, depending on where you point your torch! These events have been enormously successful with young and old who want to explore the museum in a completely different way.” These Torchlight Tours are being held as part of the ‘Museums at Night Initiative’; which is a national campaign for late night opening which capture’s people’s imaginations and encourages audiences to do something rather different with their evening ahead. The tours are on Friday 13 th of May and Saturday 14 th of May, and begin at 5:30pm, 6:30pm or 7:30pm at the Ipswich Museum. At the small cost of £4.50 per adult and £3 per child (children must be aged 8+). -

Notes on the Growth of Ipswich Museums, with a Few Diversions"

IPSWICH GEOLOGICAL GROUP BULLETIN No. 23 June 1982 CONTENTS R. A. D. Markham. "Notes on the Growth of Ipswich Museums, with a few diversions". pages 2-8. D. L. Jones. "Ipswich Museum and its Foundation. A Study in Patronage". pages 9-16. (J. E. Taylor). "The Non-Local Palaeontology Display at Ipswich Museum, 1871". pages 17-20. R. Markham. "A Note on Geology at Ipswich Museum". page 21. Page 1 NOTES ON THE GROWTH OF IPSWICH MUSEUMS, WITH A FEW DIVERSIONS. The Rev. William Kirby, rector of Barham, and natural historian and entomologist, suggested the formation of a Museum in Ipswich as long ago as 1791, but little is known of the result, if any, of this. However, in the 1820s and 1830s, museums appear to have been flourishing. Ipswich Museum was in the Corporation's old Town Hall, in an upper room near the clock, and the Literary Institution and the Mechanics Institution also had 'museums’, as did Mr. Simpson Seaman, an Ipswich natural history dealer. 1846 saw the start of a successful effort to establish a purpose-built Museum in Ipswich: the principal instigator of the plan was Mr. George Ransome of Ipswich. A Committee of Subscribers was formed, and the Committee rented a building (the first brick of which was laid the 1st. March 1847) in the then newly laid-out Museum Street. On the ground floor was the Library, the Secretary's and Curator's Rooms, and Specimen Preparation Rooms. The principal Museum Room was up the staircase. Around this room were mahogany and glass cases for animals and two cases of mahogany and glass table-cases for insects and geological specimens. -

Opportunities in the Finance

Business 16 East Monthly East Anglian Daily Times Tuesday, October 17, 2017 www.eadt.co.uk Sector skills report: Finance and business Opportunities in the finance In partnership with Suffolk County Council, Business East Monthly is running a series of reports aimed at informing young people about the career opportunities that exist in the region and the skills required to make the most of these openings. This month we provide an overview of the finance and business sector featuring interviews with employers, employees and education experts. Q&A – SUE BARNES, DIRECTOR, UK RETAIL, WILLIS TOWERS WATSON ‘We are a people-centred business and excellent interpersonal skills are essential’ Willis Towers Watson is a global willingness to learn… so quite a lot! multinational risk management, insurance brokerage and advisory How do you recruit this talent? company that operates in 140 countries We have a mixed approach to and has a major office in Ipswich. recruitment, taking on school leavers and graduates alongside targeted What is the current state of the recruitment of more experienced finance sector in East Anglia? individuals. This is a growing sector locally with We have invested heavily in growing recognised locational centres and our own talent over a number of years knowledge sectors, combined with and work closely with our internal improving communication recruiters who support us with this. infrastructure. We see individuals We also utilise specialist recruitment relocating into this area and, as there agencies to ensure we attract the right is a market here, it encourages further mix of talent so that our skill sets growth. -

Newspapers 3.Xlsx

Halesworth and District Museum – Newpaper index Printed 12/02/2018 Date Day Month Year Publication Comment Headline Location Catalogue Box Number Number 1 5 2001 ? Cutting Donation by Peter Miller, Landlord of the Triple Plea, to Patrick Stead Hospital SC/File 12 12 2003 ? Cutting Halesworth Library to open on Sundays SC/File ? Cutting Village remembers it's workhouse poor - Campaign to protect paupers' graves SC/File ? Cutting Workhouse graves row - Fury as church agrees to deconsecrate land SC/File 25 10 1957 Anglian Times 20 3 1959 Anglian Times Backtrack Cutting Southwold Railway enthusiasts visit site in 1936 SC/File 29 6 1951 Beccles & Bungay Journal Festival Queen of Halesworth, teacher from British Columbia 18 11 1977 Beccles & Bungay Journal New headquarters for Beccles Scouts & Guides U2/C/4 A412 Box Mis 1 16 12 1977 Beccles & Bungay Journal 11 5 1979 Beccles & Bungay Journal 31 8 1984 Beccles & Bungay Journal 28 9 1984 Beccles & Bungay Journal Cutting Halesworth Weekend - A triumph - including the beginnings of Halesworth Museum - Steeple End SC/File A412 Box Mis 1 23 11 1984 Beccles & Bungay Journal 7 12 1984 Beccles & Bungay Journal 21 12 1984 Beccles & Bungay Journal 12 5 1989 Beccles & Bungay Journal Cutting Halesworth Livestock Market Closes SC/File 7 2 1997 Beccles & Bungay Journal Cutting Brush-up for Halesworth Golf Club SC/File 12 12 2003 Beccles & Bungay Journal Cutting Halesworth Arts Festival - future SC/File 11 6 2004 Beccles & Bungay Journal Cutting Bus idea to curb vandalism and antisocial behaviour in Halesworth -

The Last Epidemic of Plague in England? Suffolk 1906-1918

THE LAST EPIDEMIC OF PLAGUE IN ENGLAND? SUFFOLK 1906-1918 by DAVID VAN ZWANENBERG APART from a single case of plague contracted in a laboratory at Porton in 1962 the last English outbreak of plague occurred in Suffolk. There were several official reports published soon after and there have been a number of short accounts based on these reports. This account of the epidemic was compiled with the aid of contemporary sources such as newspapers, letters, minutes of committees and coroner's depositions, together with information from one of the survivors, from several near relatives of the victims, as well as from official reports. In particular the author was fortunate in discovering a collection of letters, telegrams and other documents belonging to the late Dr. H. P. Sleigh, who was Medical Officer of Health of the Rural District of Samford at the time. THE DIAGNOSIS OF PLAGUE Five miles south of Ipswich, about halfway between the villages of Freston and Holbrook lies a small group of cottages called Latimer Cottages (see Map and Photograph). At the time that plague was first diagnosed this building was divided into three homes. In the middle cottage lived a farmworker, Mr. Chapman, his wife and four of his wife's children of a former marriage. On Tuesday, 13 September 1910, the third of these children, Annie Goodall, aged nine, was taken ill. She had not been away from home since 4 September. Following a bout of vomiting she ran a high temperature. She was seen by Dr. Carey on the following day when her temperature was 105°F, but apart from her general toxaemia he could detect no physical signs. -

The Suffolk Institute of Archaeology

THE SUFFOLKINSTITUTE OF ARCHAEOLOGY: ITS LIFE, TIMESANDMEMBERS by STEVENJ. PLUNKETT The one remains —the many change and pass' (Shelley) 1: ROOTS THE SUFFOLKINSTITUTE of Archaeology and History had its birth 150 years ago, in the spring of 1848, under the title of The Bury and West Suffolk Archaeological Institute. It is among the earliest of the County Societies, preceded only by Northamptonshire and Lincolnshire (1844), Norfolk (1846), and the Cambrian, Bedfordshire, Sussex and Buckinghamshire Societies (1847), and contemporary with those of Lancashire and Cheshire. Others, equally successful, followed, and it is a testimony to the social and intellectual timeliness of these foundations that most still flourish and produce Proceedingsdespite a century and a half of changing approaches to the historical and antiquarian materials for the study of which they were created. The immediate impetus to this movement was the formation in December 1843 of the British ArchaeologicalAssociationfor the Encouragementand Preservationof Researchesinto the Arts ancl Monumentsof theEarly and MiddleAges, which in March 1844 produced the first number of the ArchaeologicalJ ournal.The first published members' list, of 1845, shows the members grouped according to the counties in which they lived, indicating the intention that the Association should gather information from, and disseminate discourses into, the counties through a national forum. The thirty-six founding members from Suffolk form an interesting group from a varied social spectrum, including the collector Edward Acton (Grundisburgh), Francis Capper Brooke (Ufford), John Chevallier Cobbold, Sir Thomas Gery Cullum of Hawstead, David Elisha Davy, William Stevenson Fitch, the Ipswich artists Fred Russel and Wat Hagreen, Professor Henslow, Alfred Suckling, Samuel Tyrnms, John Wodderspoon, the Woodbridge geologist William Whincopp, Richard Almack, and the Revd John Mitford (editor of Gentleman'sMagazine).