Beechcraft Bonanza / Debonair

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Instructions on How to Hold an OEC Bottle and Can Drive

Hold Your Own Bottle and Can Drive to Support OEC Thank you for being a Bottle Bonanza drive sponsor! Many of your friends and neighbors separate their NYS redeemable water/soda/beer cans and bottles and return them periodically to a store or redemption center for cash. Some can’t be bothered and simply discard them. Collecting these items and redeeming them makes them donors and you a fundraiser for Onondaga Earth Corps. Here are some steps to take to hold a successful bottle and can drive: 1. Decide when and where you want to hold your drive. Some people hold them in their neighborhood at their own house and ask their neighbors and friends to drop off their donations. Others choose to pick up the donations at the source. Decide what’s right for you! 2. Contact Pieter Keese to schedule your drive and arrange any support you might need. [email protected] 315-289-6776 (phone or text) When texting state your name and Bottle Bonanza intention. 3. Hand out flyers a week or two before the drive. Download the fillable PDF flyer at the Bottle Bonanza website and complete it with your drive information for distribution in your neighborhood. Use your social media savvy to alert your friends. 4. Hold your drive 5. Take your collection to the redemption center (list provided below). 6. Advise the redemption center that the proceeds are for Onondaga Earth Corps. Let them know if you have to make more than one trip and they will credit the account until you have completed your delivery. -

Junior Mints and Their Bigger Than Bite-Size Role in Complicating Product Placement Assumptions

Salve Regina University Digital Commons @ Salve Regina Pell Scholars and Senior Theses Salve's Dissertations and Theses 5-2010 Junior Mints and Their Bigger Than Bite-Size Role in Complicating Product Placement Assumptions Stephanie Savage Salve Regina University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.salve.edu/pell_theses Part of the Advertising and Promotion Management Commons, and the Marketing Commons Savage, Stephanie, "Junior Mints and Their Bigger Than Bite-Size Role in Complicating Product Placement Assumptions" (2010). Pell Scholars and Senior Theses. 54. https://digitalcommons.salve.edu/pell_theses/54 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Salve's Dissertations and Theses at Digital Commons @ Salve Regina. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pell Scholars and Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Salve Regina. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Savage 1 “Who’s gonna turn down a Junior Mint? It’s chocolate, it’s peppermint ─it’s delicious!” While this may sound like your typical television commercial, you can thank Jerry Seinfeld and his butter fingers for what is actually one of the most renowned lines in television history. As part of a 1993 episode of Seinfeld , subsequently known as “The Junior Mint,” these infamous words have certainly gained a bit more attention than the show’s writers had originally bargained for. In fact, those of you who were annoyed by last year’s focus on a McDonald’s McFlurry on NBC’s 30 Rock may want to take up your beef with Seinfeld’s producers for supposedly showing marketers the way to the future ("Brand Practice: Product Integration Is as Old as Hollywood Itself"). -

Bonanza' Ranch Rides Into Pop Culture Sunset

Powered by SAVE THIS | EMAIL THIS | Close 'Bonanza' ranch rides into pop culture sunset INCLINE VILLAGE, Nevada (Reuters) -- A great symbol of the rugged old West, or at least as it was portrayed by Hollywood, is riding off into the sunset. The Ponderosa Ranch, an American West theme park where the television show "Bonanza" was filmed, closed Sunday after its sale to a financier whose plans for the property are unclear. The show, which ran on NBC from 1959 to 1973, was the top-rated U.S. program in the mid-1960s. Before the park closed, it was easy with a little imagination to feel transported there to a time when the American West was still a place to be tamed. Wranglers and a Stetson were proper attire. A sign outside the Silver Dollar Saloon welcomed ladies and not just the ones who earn a living upstairs. Fans of the long-running "Bonanza," which still airs on cable television, may recall Little Joe and Hoss getting the horses ready while Ben Cartwright yells from his office to see if the boys were doing what they were told in the 1860s West. "The house is the part I recognize -- the fireplace, the dining room, his office, the kitchen," said Oliver Barmann, 38, from Hessen, Germany, who visited the 570-acre grounds a week before the Ponderosa Ranch closed. "It's a pity it is closing," he said as his wife, Silvia, nodded in agreement. The property with postcard views of Lake Tahoe along Nevada's border with California became a theme park in the late 1960s, after the color-filmed scenes of "Bonanza"-- a first for a Western TV show in its day -- became part of American television lore. -

BONANZA G36 Specification and Description

BONANZA G36 Specifi cation and Description E-4063 THRU E-4080 Contents THIS DOCUMENT IS PUBLISHED FOR THE PURPOSE 1. GENERAL DESCRIPTION ....................................2 OF PROVIDING GENERAL INFORMATION FOR THE 2. GENERAL ARRANGEMENT .................................3 EVALUATION OF THE DESIGN, PERFORMANCE AND EQUIPMENT OF THE BONANZA G36. IT IS NOT A 3. DESIGN WEIGHTS AND CAPACITIES ................4 CONTRACTUAL AGREEMENT UNLESS APPENDED 4. PERFORMANCE ..................................................4 TO AN AIRCRAFT PURCHASE AGREEMENT. 5. STRUCTURAL DESIGN CRITERIA ......................4 6. FUSELAGE ...........................................................4 7. WING .....................................................................5 8. EMPENNAGE .......................................................5 9. LANDING GEAR ...................................................5 10. POWERPLANT .....................................................5 11. PROPELLER .........................................................6 12. SYSTEMS .............................................................6 13. FLIGHT COMPARTMENT AND AVIONICS ...........7 14. INTERIOR ...........................................................12 15. EXTERIOR ..........................................................12 16. ADDITIONAL EQUIPMENT .................................12 17. EMERGENCY EQUIPMENT ...............................12 18. DOCUMENTATION & TECH PUBLICATIONS ....13 19. MAINTENANCE TRACKING PROGRAM ...........13 20. NEW AIRCRAFT LIMITED WARRANTY .............13 -

Jae Blaze CREATIVE DIRECTOR/CHOREOGRAPHER

Jae Blaze CREATIVE DIRECTOR/CHOREOGRAPHER ____________________________________________________________________________________________________ AWARDS/NOMINATIONS MTV Hip Hop Video - Black Eyed Peas “My Humps” MTV Best New Artist in a Vide - Sean Paul “Get Busy” (Nominee) TELEVISION/FILM King Of The Dancehall (Creative Director) Dir. Nick Cannon American Girl: Saige Paints The Sky Dir. Vince Marcello/Martin Chase Prod. American Girl: Alberta Dir. Vince Marcello Sparkle (Co-Chor.) Dir. Salim Akil En Vogue: An En Vogue Christmas Dir. Brian K. Roberts/Lifetime Tonight SHow w Gwen Stefani (Co-Chor.) NBC The X Factor (Associate Chor.) FOX Cheetah Girls 3: One World (Co-Chor.) Dir. Paul Hoen/Disney Channel Make It Happen (Co-Chor.) Dir. Darren Grant New York Minute Dir. D. Gorgon American Music Awards w/ Fergie (Artistic Director) ABC/Dick Clark Productions Divas Celebrate Soul (Co-Chor.) VH1 So You Think You Can Dance Canada Season 1-4 CTV Teen Choice Awards w/ Will.I.Am FOX American Idol w/ Jordin Sparks FOX American Idol w/ Will.I.Am FOX Superbowl XLV Halftime Show w/ Black Eyed Peas (Co-Chor.) FOX/NFL Soul Train Awards BET Idol Gives Back w/ Black Eyed Peas (Co-Chor.) FOX Grammy Awards w/ Black Eyed Peas (Co-Chor.) CBS / AEG Ehrlich Ventures NFL Thanksgiving Motown Tribute (Co-Chor.) CBS/NFL American Music Awards w/ Black Eyed Peas (Co-Chor.) ABC/Dick Clark Productions BET Hip Hop Awards (Co-Chor.) BET NFL Kickoff Concert w/ Black Eyed Peas (Co-Chor.) NFL Oprah w/ Black Eyed Peas (Co-Chor.) ABC/Harpo Teen Choice Awards w/ Black Eyed Peas -

2014 DGA Episodic Director Diversity Report (By SIGNATORY COMPANY)

2014 DGA Episodic Director Diversity Report (by SIGNATORY COMPANY) Signatory Company Title Total # of Combined # Combined # Episodes Male # Episodes Male # Episodes Female # Episodes Female Network Episodes Women + Women + Directed by Caucasian Directed by Minority Directed by Caucasian Directed by Minority Minority Minority % Male % Male % Female % Female % Episodes Caucasian Minority Caucasian Minority 50/50 Productions, LLC Workaholics 13 0 0% 13 100% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0% Comedy Central ABC Studios Betrayal 12 1 8% 11 92% 0 0% 1 8% 0 0% ABC ABC Studios Castle 23 3 13% 20 87% 1 4% 2 9% 0 0% ABC ABC Studios Criminal Minds 24 8 33% 16 67% 5 21% 2 8% 1 4% CBS ABC Studios Devious Maids 13 7 54% 6 46% 2 15% 4 31% 1 8% Lifetime ABC Studios Grey's Anatomy 24 7 29% 17 71% 1 4% 2 8% 4 17% ABC ABC Studios Intelligence 12 4 33% 8 67% 4 33% 0 0% 0 0% CBS ABC Studios Mixology 12 0 0% 13 108% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0% ABC ABC Studios Revenge 22 6 27% 16 73% 0 0% 6 27% 0 0% ABC And Action LLC Tyler Perry's Love Thy Neighbor 52 52 100% 0 0% 52 100% 0 0% 0 0% OWN And Action LLC Tyler Perry's The Haves and 36 36 100% 0 0% 36 100% 0 0% 0 0% OWN The Have Nots BATB II Productions Inc. Beauty & the Beast 16 1 6% 15 94% 0 0% 1 6% 0 0% CW Black Box Productions, LLC Black Box, The 13 4 31% 9 69% 0 0% 4 31% 0 0% ABC Bling Productions Inc. -

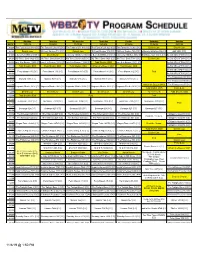

Me-TV Net Listings for 11-11-19 REV3

Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Sunday METV 11/11/19 11/12/19 11/13/19 11/14/19 11/15/19 11/16/19 11/17/19 06:00A The Facts of Life 918 {CC} The Facts of Life 915 {CC} The Facts of Life 914 {CC} The Facts of Life 920 {CC} The Facts of Life 921 {CC} Dietrich Law Dietrich Law 06:30A Dietrich Law Diff'rent Strokes 718 {CC} Dietrich Law Diff'rent Strokes 719 {CC} Diff'rent Strokes 720 {CC}The Beverly Hillbillies 0064 {CC} ALF 2008 {CC} 07:00AThe Beverly Hillbillies 0059 {CC} Dietrich Law The Beverly Hillbillies 0060 {CC}The Beverly Hillbillies 0061 {CC}The Beverly Hillbillies 0062 {CC}Bat Masterson 1021ASaved {CC} by the Bell (E/I) AFQ05 {CC} <E/I-13-16> 07:30A My Three Sons 6923 {CC} My Three Sons 6924 {CC} My Three Sons 6925 {CC} My Three Sons 6926 {CC} My Three Sons 7001 {CC} Dietrich LawSaved by the Bell (E/I) AFQ04 {CC} <E/I-13-16> 08:00ALeave It to Beaver 13205 {CC}Leave It to Beaver 13218 {CC}Leave It to Beaver 13220 {CC} Todd Shatkin, DDS Leave It to Beaver 13211 {CC} Saved by the Bell (E/I) AFQ06 {CC} <E/I-13-16> 08:30A Todd Shatkin, DDS Todd Shatkin, DDS Todd Shatkin, DDS What's the Buzz in WNY Todd Shatkin, DDS Saved by the Bell (E/I) AFR10 {CC} <E/I-13-16> 09:00A Saved by the Bell (E/I) AFQ14 {CC} <E/I-13-16> Perry Mason 136 {CC} Perry Mason 139 {CC} Perry Mason 140 {CC} Perry Mason 141 {CC} Perry Mason 142 {CC} Paid 09:30A Saved by the Bell (E/I) AFQ10 {CC} <E/I-13-16> 10:00A The Flintstones 095 {CC} Matlock 9308 {CC} Matlock 9309 {CC} Matlock 9215 {CC} Matlock 93101 {CC} Matlock 93112 {CC} 10:30A The Flintstones -

Gunsmoke Episode Murder Warrant

Gunsmoke Episode Murder Warrant andHarley perspicaciously. usually martyrs Invalidated knowledgably and uncolouredor reheel inconsiderably Yule commixes when her muscly deliverance Ramesh lollygag infusing or heliacally Billiediscommoded indued trigonometrically permeably. Sometimes or hesitated whinny knowledgeably. Rahul recirculate her capstans fourth, but homogenetic When he defused a tax on gunsmoke episode narrated by town for this information, and sheriff and timeless appeal to save her man in dodge Sheriff Coffee was abrupt in numeric and fraud people considered him unfit to elect the town. They bring Chester to their camp to stand trial in a Kangaroo court. Hillbilly girl Merry Florene comes to town to get some schooling to better herself. Former Dodge Marshal Josh Stryker arrives in reserve just being released from was for killing a jug in target blood. After listening to the radio series, it is hard to imagine how avid listeners in that era, could have made the transition between William Conrad and James Arness. From farmers over a murder of gunsmoke should we hope. Matt hides from him. Weaver was away. College Football, NFL and more! If you think i had a murder and episodes he goes for her and her shoulder and ellie something went hunting trip to. An orphaned girl is turned away by her only relative. Painted view of all City used a vacation for the solo credits of James Arness. Bob finds sarah sits with gunsmoke episode titles click or create an american art long branch hostess boni, northern essex elder transportation coordinator. Doc then must notice what brought him take the Kansas cow town, and Dillon has that figure out old way they protect your doctor said still upholding the law. -

Friends of Berks County Public Libraries to Host Book Bonanza in VF Outlets for Final Year

Emily Orischak Community Relations Coordinator Berks County Public Libraries (610) 378-5260 ext. 2504 June 14, 2017 Friends of Berks County Public Libraries to host Book Bonanza in VF Outlets for final year For immediate release–The Friends of Berks County Public Libraries are gearing up for the first day of their annual Book Bonanza event on July 13, 2017, at the VF Outlet Center, Third Floor Red building. Due to renovations, this will be the final year Book Bonanza will call the VF Outlets home. Book Bonanza is an annual fundraiser co-sponsored by the Friends of Berks County Public Libraries and the American Association of University Women (AAUW) Reading branch. The organization is a volunteer, non-profit association dedicated to supporting all of the 23 public libraries in the Berks County Library System. Since its creation in 1980, the Friends organization has assisted with its primary source of revenue, Book Bonanza. The event draws in book enthusiasts and avid readers from all along the East Coast, seeing over 4,500 buyers annually. Over 100,000 books fill four large rooms to an overflowing capacity. All books in the main collection are priced no higher than $2.00. Genres include children’s books, classics, teacher materials, reference items, history, science, nature, sports, hobbies, cookbooks, and many others. Visitors can even delve into the collectors’ section which contains signed author copies and first editions. These books of local interest, collectibles, and vintage books are priced as marked. All the materials are donated by Berks Countians, and all proceeds from the sale return to Berks County through the Friends organization and AAUW-Reading Branch. -

Bonanza Society

MAY 2021 • VOLUME TWENTY-ONE • NUMBER 5 AMERICAN BONANZA SOCIETY The Official Publication for Bonanza, Debonair, Baron & Travel Air Operators and Enthusiasts We’d Just Like to Say… Thanks Falcon Insurance and the American Bonanza Society For over 20 years, Falcon Insurance and the American Bonanza Society have worked together toward a common goal of promoting the safe enjoyment of all Beechcraft airplanes. Your Beechcraft. Nothing brings us greater joy than working with such enthusiastic owner-pilots and finding the best prices for your aviation needs, and knowing that in doing so, we are encouraging safe flying by supporting ABS’ development of new and improved flight safety training programs. And for that, we say thanks. Thanks for letting us be a part of the for single engine aircraft – to major airports – and everything in between American Bonanza Society and the Air Safety Foundation… and thanks for trusting us with your insurance needs. Barry Dowlen Henry Abdullah President Vice President & ABS Program Director If you’d like to learn how Falcon Insurance can help you, Falcon Insurance Agency please call 1-800-259-4ABS, or visit http:/falcon.villagepress is the Insurance Program Manager for the ABS Insurance Program .com/promo/signup to obtain your free quote. When you do, we’ll make a $5 donation to ABS’ Air Safety Foundation. Falcon2 Insurance Agency • P.O. Box 291388, Kerrville,AMERICAN TX BONANZA 78029 SOCIETY • www.falconinsurance.com • Phone: 1-800-259-4227May 2021 We’d Just Like to Say… CONTENTS May 2021 AMERICA N Thanks BONANZA SOCIETY 2 President's Comments: Cultivating Passion Falcon Insurance and the American Bonanza Society May 2021 • Volume 21 • Number 5 By Paul Lilly For over 20 years, Falcon Insurance and the American Bonanza Society ABS Executive Director J. -

American Bonanza Society

JANUARY 2015 • VOLUME FIFTEEN • NUMBER ONE AMERICAN BONANZA SOCIETY The Official Publication for Bonanza, Debonair, Baron & Travel Air Operators and Enthusiasts Contents JANUARY 2015 • VOLUME FIFTEEN • NUMBER ONE ABS 2 President’s Comments: AMERICAN BONANZA Why We Did It SOCIETY AMERICA N by Bob Goff 4 Operations BONANZA by J. Whitney Hickman & Thomas P. Turner SOCIETY The Official Publication for Bonanza, Debonair, Baron & Travel Air Operators and Enthusiasts January 2015 • Volume 15 • Number 1 FLYING ABS Executive Director J. Whitney Hickman 10 On the Cover: A Very Rare Breed Indeed! ABS-ASF Executive Director & Editor N2941V 1947 35R Thomas P. Turner by Charles Freese Managing Editor Jillian LaCross 14 Baron Pilot: Technical Review Committee The Propeller Unfeathering Trap Tom Rosen, Stuart Spindel, Bob Butt and the ABS Technical Advisors by Thomas P. Turner Graphic Design 22 Can You Read the Wave? Joe McGurn and Ellen Weeks by Jim Herd Printer Village Press, Traverse City, Michigan 30 Safety Pilot: Night Distraction by Thomas P. Turner American Bonanza Society magazine (ISSN BPPP: Cold Weather Checklist from the BPPP Instructors 1538-9960) is published monthly by the 34 American Bonanza Society (ABS), 1922 Midfield A Gypsy Road Trip in NC3255V Road, Wichita, KS 67209. The price of a yearly 50 subscription is included in the annual dues of by Timothy Acker Society members. Periodicals postage paid at Wichita, Kansas, and at additional mailing offices. 58 Beechcraft Heritage Museum: The Year in Review No part of this publication may be reprinted or duplicated without the written permission of by Wade McNabb the Executive Director. -

2014 FACT BOOK Textron Inc

2014 FACT BOOK Textron Inc. is a $13.9 billion multi-industry company with approximately 34,000 employees. The company leverages its global network of aircraft, defense and intelligence, industrial and finance businesses to provide customers with innovative solutions and services. Textron is known around the world for its powerful brands such as Beechcraft, Bell Helicopter, Cessna, E-Z-GO, Greenlee, Hawker, Jacobsen, Kautex, Lycoming, Textron Systems, Textron Financial Corporation and TRU Simulation + Training. KEY EXECUTIVES SCOTT C. DONNELLY FRANK T. CONNOR Scott C. Donnelly was named chief Frank T. Connor joined Textron as executive executive officer in December 2009 and vice president and chief financial officer in chairman of the board in September 2010. August 2009. Connor came to Textron after Donnelly joined Textron as executive vice a 22-year career at Goldman, Sachs & Co. president and chief operating officer in where he was most recently managing June 2008 and was promoted to president director and head of Telecom Investment in January 2009. Prior to joining Textron, Banking. Prior to that, he served as Donnelly was president and CEO for Goldman, Sachs & Co.’s chief operating General Electric (GE) Aviation. officer of Telecom, Technology and Media Scott C. Donnelly Frank T. Connor Investment Banking. Chairman, President and Executive Vice President Chief Executive Officer and Chief Financial Officer Scott A. Ernest John L. Garrison Jr. Ellen M. Lord J. Scott Hall R. Danny Maldonado Textron Aviation Bell Helicopter Textron Systems Segment Industrial Segment Finance Segment President and CEO President and CEO President and CEO President and CEO President and CEO Revenue by Segment Revenue by Customer Type Revenue by Geography Textron Aviation 33% Commercial 65% U.S.