Physician-Industry Interactions: Persuasion and Welfare

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Side Effects of Labor Market Policies

DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES IZA DP No. 13846 Side Effects of Labor Market Policies Marco Caliendo Robert Mahlstedt Gerard J. van den Berg Johan Vikström NOVEMBER 2020 DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES IZA DP No. 13846 Side Effects of Labor Market Policies Marco Caliendo University of Potsdam, IZA, DIW and IAB Robert Mahlstedt University of Copenhagen and IZA Gerard J. van den Berg University of Bristol, University of Groningen, IFAU, IZA, ZEW, CEPR, CESifo and UCLS Johan Vikström IFAU, Uppsala University and UCLS NOVEMBER 2020 Any opinions expressed in this paper are those of the author(s) and not those of IZA. Research published in this series may include views on policy, but IZA takes no institutional policy positions. The IZA research network is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The IZA Institute of Labor Economics is an independent economic research institute that conducts research in labor economics and offers evidence-based policy advice on labor market issues. Supported by the Deutsche Post Foundation, IZA runs the world’s largest network of economists, whose research aims to provide answers to the global labor market challenges of our time. Our key objective is to build bridges between academic research, policymakers and society. IZA Discussion Papers often represent preliminary work and are circulated to encourage discussion. Citation of such a paper should account for its provisional character. A revised version may be available directly from the author. ISSN: 2365-9793 IZA – Institute of Labor Economics Schaumburg-Lippe-Straße 5–9 Phone: +49-228-3894-0 53113 Bonn, Germany Email: [email protected] www.iza.org IZA DP No. -

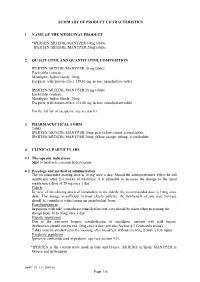

Summary of Product Characteristics

SUMMARY OF PRODUCT CHARACTERISTICS 1 NAME OF THE MEDICINAL PRODUCT *IPERTEN/ARTEDIL/MANYPER 10mg tablets IPERTEN/ARTEDIL/MANYPER 20mg tablets 2. QUALITATIVE AND QUANTITATIVE COMPOSITION IPERTEN/ARTEDIL/MANYPER 10 mg tablets Each tablet contains: Manidipine hydrochloride 10mg Excipient with known effect: 119,61 mg lactose monohydrate/tablet IPERTEN/ARTEDIL/MANYPER 20 mg tablets Each tablet contains: Manidipine hydrochloride 20mg Excipient with known effect: 131,80 mg lactose monohydrate/tablet For the full list of excipients, see section 6.1. 3. PHARMACEUTICAL FORM Tablet IPERTEN/ARTEDIL/MANYPER 10mg: pale yellow, round, scored tablet; IPERTEN/ARTEDIL/MANYPER 20mg: yellow-orange, oblong, scored tablet. 4. CLINICAL PARTICULARS 4.1 Therapeutic indications Mild to moderate essential hypertension 4.2 Posology and method of administration The recommended starting dose is 10 mg once a day. Should the antihypertensive effect be still insufficient after 2-4 weeks of treatment, it is advisable to increase the dosage to the usual maintenance dose of 20 mg once a day. Elderly In view of the slowing down of metabolism in the elderly, the recommended dose is 10mg once daily. This dosage is sufficient in most elderly patients; the risk/benefit of any dose increase should be considered with caution on an individual basis. Renal impairment In patients with mild to moderate renal dysfunction care should be taken when increasing the dosage from 10 to 20mg once a day. Hepatic impairment Due to the extensive hepatic metabolisation of manidipine, patients with mild hepatic dysfunction should not exceed 10mg once a day (see also Section 4.3 Contraindications). Tablet must be swallowed in the morning after breakfast, without chewing it, with a few liquid. -

The Repurposing Drugs in Oncology Database

ReDO_DB: the repurposing drugs in oncology database Pan Pantziarka1,2, Ciska Verbaanderd1,3, Vidula Sukhatme4, Rica Capistrano I1, Sergio Crispino1, Bishal Gyawali1,5, Ilse Rooman1,6, An MT Van Nuffel1, Lydie Meheus1, Vikas P Sukhatme4,7 and Gauthier Bouche1 1The Anticancer Fund, Brussels, 1853 Strombeek-Bever, Belgium 2The George Pantziarka TP53 Trust, London, UK 3Clinical Pharmacology and Pharmacotherapy, Department of Pharmaceutical and Pharmacological Sciences, KU Leuven, Leuven, Belgium 4GlobalCures Inc., Newton, MA 02459 USA 5Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02115 USA 6Oncology Research Centre, Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Brussels, Belgium 7Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA 30322 USA Correspondence to: Pan Pantziarka. Email: [email protected] Abstract Repurposing is a drug development strategy that seeks to use existing medications for new indications. In oncology, there is an increased level of activity looking at the use of non-cancer drugs as possible cancer treatments. The Repurposing Drugs in Oncology (ReDO) project has used a literature-based approach to identify licensed non-cancer drugs with published evidence of anticancer activity. Data from 268 drugs have been included in a database (ReDO_DB) developed by the ReDO project. Summary results are outlined and an assessment Research of clinical trial activity also described. The database has been made available as an online open-access resource (http://www.redo-project. org/db/). Keywords: drug repurposing, repositioning, ReDO project, cancer drugs, online database Published: 06/12/2018 Received: 27/09/2018 ecancer 2018, 12:886 https://doi.org/10.3332/ecancer.2018.886 Copyright: © the authors; licensee ecancermedicalscience. -

Welfare Effects of Physician-Industry Interactions: Evidence from Patent

Welfare Effects of Physician-industry Interactions: Evidence From Patent Expiration (PRELIMINARY — do not cite without permission) Aaron Chatterji∗, Matthew Grennany, Kyle Myersz, Ashley Swansony December 29, 2017 Abstract Many transactions occur via expert advisors, especially in the healthcare sector, and as such, firms frequently implement strategies to influence these advisors. The effi- ciency of these interactions is an empirical question. Using data on physician-industry interactions and prescribing behavior during the entry of a major generic statin drug, we examine the causal effect and welfare implications of the most common type of interaction: meals. Guided by a theoretical model of endogenous meals, we develop an instrumental variables identification strategy and document reduced form evidence that these meals directly influence prescribing decisions. We find a significant degree of negative selection and primarily extensive margin effects, whereby firms target small meals to prescribers with an otherwise low propensity to use the target drug. Given this evidence, we estimate a structural model of drug choice that allows us to predict counterfactual outcomes in a world where these meals are banned. Results from these counterfactuals are in line with theoretical predictions that these interactions can offset efficiency losses due to pricing with market power. However, this offset does not appear large enough to justify their existence in this particular market. ∗Duke University, The Fuqua School & NBER yUniversity of Pennsylvania, The Wharton School & NBER zNBER Please direct correspondence to [email protected]. The data used in this paper were generously provided, in part, by the Kyruus, Inc. We gratefully acknowledge financial support from the Wharton Dean’s Research Fund, Mack Institute, and Public Policy Initiative. -

1.5Mg Prolonged-Release Tablets Indapamide

SUMMARY OF PRODUCT CHARACTERISTICS 1 NAME OF THE MEDICINAL PRODUCT /…/ 1.5 mg Prolonged-release Tablets. 2 QUALITATIVE AND QUANTITATIVE COMPOSITION Each prolonged-release tablet contains 1.5 mg of indapamide. Excipient with known effect: 144.22 mg of lactose monohydrate/prolonged-release tablet For the full list of excipients, see section 6.1. 3 PHARMACEUTICAL FORM Prolonged-release tablet White to off white, round, biconvex prolonged-release film-coated tablets. 4 CLINICAL PARTICULARS 4.1 Therapeutic indications Essential hypertension. 4.2 Posology and method of administration Posology One tablet per 24 hours, preferably in the morning, to be swallowed whole with water and not chewed. At higher doses the antihypertensive action of indapamide is not enhanced but the saluretic effect is increased. Renal failure (see sections 4.3 and 4.4) In severe renal failure (creatinine clearance below 30 ml/min), treatment is contraindicated. Thiazide and related diuretics are fully effective only when renal function is normal or only minimally impaired. Elderly (see section 4.4) In the elderly, this plasma creatinine must be adjusted in relation to age, weight and gender. Elderly patients can be treated with /…/ 1.5 mg Prolonged-release Tablets when renal function is normal or only minimally impaired. Patients with hepatic impairment (see sections 4.3 and 4.4) In severe hepatic impairment, treatment is contraindicated. Children and adolescents: /…/ 1.5 mg Prolonged-release Tablets are not recommended for use in children and adolescents due to a lack of data on safety and efficacy. Method of administration For oral administration. 4.3 Contraindications - Hypersensitivity to indapamide, other sulfonamides or to any of the excipients listed in section 6.1. -

Investigations Into the Role of Nitric Oxide in Disease

INVESTIGATIONS INTO THE ROLE OF NITRIC OXIDE IN CARDIOVASCULAR DEVXLOPMENT DISEASE: INSIGHTS GAINED FROM GENETICALLY ENGINEERED MOUSE MODELS OF HUMAN DISEASE Tony Lee A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master's of Science Institute of Medicai Science University of Toronto @ Copyright by Tony C. Lee (2000) National Library Bibliothèque nationale I*I of Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliogaphic Services services bibliogaphiques 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Ottawa ON KIA ON4 Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microfonn, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/nlm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fkom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or othewise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. INVESTIGATIONS INTO THE ROLE OF MTNC OXIDE IN CARDIOVASCULAR DEVELOPMENT AND DISEASE: INSIGHTS GAiNED FROM GENETICALLY ENGINEERED MOUSE MODELS OF HUMAN DISEASE B y Tony Lee A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master's of Science (2000) Instinite of Medical Science, University of Toronto In the first expenmental series, the antiatherosclerotic effects of Enalûpril vrrsus Irbesartan were compared in the LDL-R knockout mouse model. -

Summary of Product Characteristics

SUMMARY OF PRODUCT CHARACTERISTICS 1. NAME OF THE MEDICINAL PRODUCT Isalok 2. QUALITATIVE AND QUANTITATIVE COMPOSITION Each prolonged-release tablet contains 23.75 mg metoprolol succinate equivalent to 25 mg metoprolol tartrate. 47.5 mg metoprolol succinate equivalent to 50 mg metoprolol tartrate. 95 mg metoprolol succinate equivalent to 100 mg metoprolol tartrate. 190 mg metoprolol succinate equivalent to 200 mg metoprolol tartrate. For a full list of excipients, see section 6.1. 3. PHARMACEUTICAL FORM Prolonged-release tablet Metoprolol succinate, 23.75 mg, prolonged release tablet is a white, oval biconvex, film- coated tablet, approx. 9 by 5 mm, scored on both sides. Metoprolol succinate 47.5 mg, prolonged release tablet is a white, oval biconvex film- coated tablet, approx. 11 by 6 mm, scored on both sides. Metoprolol succinate 95 mg, prolonged release tablet is a white, oval biconvex, film- coated tablet, approx. 16 by 8 mm, scored on both sides. Metoprolol succinate 190 mg, prolonged release tablet is a white, oval biconvex, film- coated tablet, approx. 19 by 10 mm scored on both sides. The tablets can be divided into equal halves. 4. CLINICAL PARTICULARS 4.1 Therapeutic indications – Hypertension – Angina pectoris – Heart arrhythmia, particularly supraventricular tachycardia – Prophylactic treatment to prevent cardiac death and re-infarction following the acute phase of a myocardial infarction – Palpitations due to functional cardiac disorders – Prophylaxis of migraine – Stable symptomatic heart failure (NYHA II-IV, left ventricular ejection fraction < 40 %), combined with other therapies for heart failure (see section 5.1). 4.2 Posology and method of administration Metoprolol succinate tablets should be taken once daily in the morning. -

Summary of Product Characteristics

SUMMARY OF PRODUCT CHARACTERISTICS 1. NAME OF THE MEDICINAL PRODUCT Quinapril 40 mg film-coated tablets 2. QUALITATIVE AND QUANTITATIVE COMPOSITION Quinapril 40 mg tablets contain quinapril hydrochloride equivalent to 40 mg quinapril per tablet, respectively. For a full list of excipients, see section 6.1. 3. PHARMACEUTICAL FORM Film-coated tablets. The 40 mg tablets are reddish-brown in colour and round. 4. CLINICAL PARTICULARS 4.1 Therapeutic indications Essential hypertension and congestive heart failure. 4.2 Posology and method of administration The absorption of quinapril is not affected by food. The tablets should be swallowed with a glass of water. The tablets should not be chewed. If the recommended dose could not be achieved with quinapril 40 mg tablets other strengths are available. Essential hypertension Monotherapy: The recommended initial dosage of quinapril is 10 mg once daily. Depending upon clinical response, the dosage may be titrated (by doubling the dose) to a maintenance dose of 20 to 40 mg daily, given once daily or divided into 2 doses. Long-term control is maintained in most patients with a single daily dosage regimen. Patients have been treated with doses up to 80 mg daily. Concomitant diuretics: In patients who are being treated with a diuretic, the initial dose is 5 mg. After this the dose should be titrated (as described above) to the optimal response. Symptomatic hypotension may occur after the first dose of quinapril; this is more likely in patients with diuretic treatment. Caution should therefore be exercised because these patients may be volume- or salt-depleted. Renal impairment Kinetic data have shown that the apparent half-life of quinaprilat is prolonged as creatinine clearance falls. -

Impact of the World Health Organization Pain Treatment

medicina Article Impact of the World Health Organization Pain Treatment Guidelines and the European Medicines Agency Safety Recommendations on Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drug Use in Lithuania: An Observational Study Skaiste˙ Kasciuškeviˇciut¯ e˙ 1,* ID , Gintautas Gumbreviˇcius 1, Aušra Vendzelyte˙ 2, Arunas¯ Šˇciupokas 3 ID , K˛estutisPetrikonis 3 and Edmundas Kaduševiˇcius 1 1 Division of Clinical Pharmacology, Institute of Physiology and Pharmacology, Medical Academy, Lithuanian University of Health Sciences, 44307 Kaunas, Lithuania; [email protected] (G.G.); [email protected] (E.K.) 2 Faculty of Pharmacy, Medical Academy, Lithuanian University of Health Sciences, 44307 Kaunas, Lithuania; [email protected] 3 Department of Neurology, Medical Academy, Lithuanian University of Health Sciences, 44307 Kaunas, Lithuania; [email protected] (A.S.); [email protected] (K.P.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +37-060-304-903 Received: 27 February 2018; Accepted: 8 May 2018; Published: 11 May 2018 Abstract: Background and objective: Irrational use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) is the main cause of adverse effects-associated hospitalizations among all medication groups leading to extremely increased costs for health care. Pharmacoepidemiological studies can partly reveal such issues and encourage further decisions. Therefore, the aim of our study was to evaluate the utilization of non-opioid analgesics (ATC classification N02B and M01A) in Lithuania, and to compare it with that of other Baltic and Scandinavian countries in terms of compliance to the WHO pain treatment guidelines and the EMA safety recommendations on NSAID use. Materials and methods: The dispensing data were obtained from the sales analysis software provider in the Baltic countries (SoftDent, Ltd., Kaunas, Lithuania); State Medicine Control Agencies of Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia; Norwegian Prescription Database; Swedish Database for Medicines; and Danish Prescription Database. -

APSA-ASCEPT 2015 Book of Abstracts - ORAL

100 And then there were three – lessons from a convoluted drug development project Martin C. Michel, Dept. Pharmacology, Johannes Gutenberg University, Mainz, Germany The existence of β3-adrenoceptors (B3AR) only became accepted after its cloning in 1989. Initial attempts to develop B3AR-targeted drugs for the treatment of obesity and type 2 diabetes failed, because species differences in ligand recognition profiles, tissue distribution and functional role had been underappreciated. Around the year 2000 some of these programs were repurposed to develop B3AR agonists as treatment of the overactive bladder syndrome. The translational pharmacology programs accompanying the clinical development of B3AR agonists faced several challenges. First, concepts of the pathophysiology underlying urinary bladder dysfunction were only poorly developed and have considerably emerged in the past 15 years. Specifically, the smooth muscle-centric view of bladder function changed into a multi-player concept including urothelium, afferent nerves and blood vessels. This questioned the original rationale for B3AR agonists, which had been based on muscle strip experiments. Second, the overall role of B3AR in humans was largely unknown and no validated tools existed for their detection at the protein level, complicating prediction of possible side effects in patients. Third, the selectivity of pharmacological tools for functional studies was limited, often leading to false conclusions. Fourth, B3AR polymorphisms had been described but their impact on target function was controversial. Fifth, generating meaningful selectivity in agonists is much more difficult than in antagonists as cells expressing another receptor subtype but high receptor reserve may show responses even if the agonist occupies only a minor fraction of these receptors. -

Pharmacoepidemiological Profile and Polypharmacy Indicators in Elderly Outpatients

Brazilian Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences vol. 49, n. 3, jul./sep., 2013 Article Pharmacoepidemiological profile and polypharmacy indicators in elderly outpatients André de Oliveira Baldoni1,*, Lorena Rocha Ayres1, Edson Zangiacomi Martinez2, Nathalie de Lourdes Sousa Dewulf3, Vânia dos Santos4, Paulo Roque Obreli-Neto5, Leonardo Régis Leira Pereira1 1Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, School of Pharmaceutical Sciences of Ribeirão Preto, University of São Paulo, Ribeirão Preto, SP, Brazil, 2Department of Social Medicine, School of Medicine Ribeirão Preto, University of São Paulo, Ribeirão Preto, SP, Brazil, 3School of Farmacy, Federal University of Goiás, Goiânia, GO, Brazil, 4Department of Clinical, Toxicological and Bromatological Analyses, School of Pharmaceutical Sciences of Ribeirão Preto, University of São Paulo, Ribeirão Preto, SP, Brazil, 5Department of Pharmacology and Therapeutics, State University of Maringá, Maringá, PR, Brazil This cross-sectional study was carried out with 1000 elderly outpatients assisted by a Basic Health District Unit (UBDS) from the Brazilian Public Health System (SUS) in the municipality of Ribeirão Preto. We analyzed the clinical, socioeconomic and pharmacoepidemiological profile of the elderly patients in order to identify factors associated with polypharmacy amongst this population. We used a truncated negative binomial model to examine the association of polypharmacy with the independent variables of the study. The software SAS was used for the statistical analysis and the significance level adopted was 0.05. The most prevalent drugs were those for the cardiovascular system (83.4%). There was a mean use of seven drugs per patient and 47.9% of the interviewees used ≥7 drugs. The variables that showed association with polypharmacy (P value < 0.01) were female gender, age >75 years, self-medication, number of health problems, number of medical appointments, presence of adverse drug events, use of over-the-counter drugs, use of psychotropic drugs, lack of physical exercise and use of sweeteners. -

Overview Final Guidance

Amlodipine, NL/H/882/001-002, 27.08.19 SUMMARY OF PRODUCT CHARACTERISTICS 1/13 Amlodipine, NL/H/882/001-002, 27.08.19 1 NAME OF THE MEDICINAL PRODUCT Amlodipine CT 5 mg, tablets Amlodipine CT 10 mg, tablets 2 QUALITATIVE AND QUANTITATIVE COMPOSITION Amlodipine 5 mg, tablets Each tablet contains 5 mg amlodipine (as amlodipine besilate). Amlodipine 10 mg, tablets Each tablet contains 10 mg amlodipine (as amlodipine besilate). For the full list of excipients, see section 6.1. 3 PHARMACEUTICAL FORM Tablet Amlodipine 5 mg, tablets White, round tablet. One side is slightly concave with breakline and debossed “A5”. The other side is slightly convex and plain. The tablet can be divided into equal doses. Amlodipine 10 mg, tablets White, round tablet. One side is slightly concave with breakline and debossed “A10”. The other side is slightly convex and plain. The tablet can be divided into equal doses. 4 CLINICAL PARTICULARS 4.1 Therapeutic indications Hypertension Chronic stable angina pectoris Vasospastic (Prinzmetal’s) angina 4.2 Posology and method of administration Posology Adults For both hypertension and angina the usual initial dose is 5 mg amlodipine once daily which may be increased to a maximum dose of 10 mg depending on the individual patient's response. In hypertensive patients, amlodipine has been used in combination with a thiazide diuretic, alpha blocker, beta blocker, or an angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor. For angina, amlodipine may be used as monotherapy or in combination with other antianginal medicinal products in patients with angina that is refractory to nitrates and/or to adequate doses of beta blockers.