Access and Mobility in Gauteng's Priority Townships What Can The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Provincial Gazette Provinsiale Koerant EXTRAORDINARY • BUITENGEWOON

THE PROVINCE OF DIE PROVINSIE VAN UNITY DIVERSITY GAUTENG IN GAUTENG Provincial Gazette Provinsiale Koerant EXTRAORDINARY • BUITENGEWOON Selling price • Verkoopprys: R2.50 Other countries • Buitelands: R3.25 PRETORIA Vol. 25 18 SEPTEMBER 2019 No. 289 18 SEPTEMBER 2019 We oil Irawm he power to pment kiIDc AIDS HElPl1NE 0800 012 322 DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH Prevention is the cure ISSN 1682-4525 N.B. The Government Printing Works will 00289 not be held responsible for the quality of “Hard Copies” or “Electronic Files” submitted for publication purposes 9 771682 452005 2 No. 289 PROVINCIAL GAZETTE, EXTRAORDINARY, 18 SEPTEMBER 2019 IMPORTANT NOTICE OF OFFICE RELOCATION GOVERNMENT PRINTING WORKS PUBLICATIONS SECTION Dear valued customer, We would like to inform you that with effect from the 1st of November 2019, the Publications Section will be relocating to a new facility at the corner of Sophie de Bruyn and Visagie Street, Pretoria. The main telephone and facsimile numbers as well as the e-mail address for the Publications Section will remain unchanged. Our New Address: 88 Visagie Street Pretoria 0001 Should you encounter any difficulties in contacting us via our landlines during the relocation period, please contact: Ms Maureen Toka Assistant Director: Publications Cell: 082 859 4910 Tel: 012 748-6066 We look forward to continue serving you at our new address, see map below for our new location. C1ty Of Tshwané J Municipal e , I I r e ;- e N 4- 4- Loreto Convent _-Y School, Pretoria ITShwane L e UMttersi Techrtolog7 Government Printing Works Publications _PAl11TGl l LMintys Tyres Pretori solest Star 88 Visagie Street Q II _ 4- Visagie St Visagie St 9 Visagie St F e Visagie St Visal Government Printing Works Waxing National Museum of Cultural- Malas Drive Style Centre Tshwane á> 9 The old Fire Station, PretoriaCentralo Minnaar St Minnaar St o Minnaar p 91= tarracks This gazette is also available free online at www.gpwonline.co.za PROVINSIALE KOERANT, BUITENGEWOON, 18 SEPTEMBER 2019 No. -

Alberton / Thokoza Load Shedding Schedule DAYS of the MONTH DAY TIME 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31

Alberton / Thokoza Load Shedding Schedule DAYS OF THE MONTH DAY TIME 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 00h00 - 03h00 B1 B2 B3 B4 B5 B6 B1 B2 B3 B4 B5 B6 B1 B2 B3 B4 B5 B6 B1 B2 B3 B4 B5 B6 B1 B2 B3 B4 B5 B6 B1 02h30 - 05h30 B6 B1 B2 B3 B4 B5 B6 B1 B2 B3 B4 B5 B6 B1 B2 B3 B4 B5 B6 B1 B2 B3 B4 B5 B6 B1 B2 B3 B4 B5 B6 05h00 - 08h00 B5 B6 B1 B2 B3 B4 B5 B6 B1 B2 B3 B4 B5 B6 B1 B2 B3 B4 B5 B6 B1 B2 B3 B4 B5 B6 B1 B2 B3 B4 B5 07h30 - 10h30 B4 B5 B6 B1 B2 B3 B4 B5 B6 B1 B2 B3 B4 B5 B6 B1 B2 B3 B4 B5 B6 B1 B2 B3 B4 B5 B6 B1 B2 B3 B4 10h00 - 13h00 B3 B4 B5 B6 B1 B2 B3 B4 B5 B6 B1 B2 B3 B4 B5 B6 B1 B2 B3 B4 B5 B6 B1 B2 B3 B4 B5 B6 B1 B2 B3 12h30 - 15h30 B2 B3 B4 B5 B6 B1 B2 B3 B4 B5 B6 B1 B2 B3 B4 B5 B6 B1 B2 B3 B4 B5 B6 B1 B2 B3 B4 B5 B6 B1 B2 15h00 - 18h00 B1 B2 B3 B4 B5 B6 B1 B2 B3 B4 B5 B6 B1 B2 B3 B4 B5 B6 B1 B2 B3 B4 B5 B6 B1 B2 B3 B4 B5 B6 B1 17h30 - 20h30 B6 B1 B2 B3 B4 B5 B6 B1 B2 B3 B4 B5 B6 B1 B2 B3 B4 B5 B6 B1 B2 B3 B4 B5 B6 B1 B2 B3 B4 B5 B6 20h00 - 23h00 B5 B6 B1 B2 B3 B4 B5 B6 B1 B2 B3 B4 B5 B6 B1 B2 B3 B4 B5 B6 B1 B2 B3 B4 B5 B6 B1 B2 B3 B4 B5 22h30 - 24h00 B4 B5 B6 B1 B2 B3 B4 B5 B6 B1 B2 B3 B4 B5 B6 B1 B2 B3 B4 B5 B6 B1 B2 B3 B4 B5 B6 B1 B2 B3 B4 B1 AREAS Randhart Ext 1& 2, General Alberts Park and Randhart B2 AREAS Raceview, Southcrest, Newmarket (Pick n Pay), New-Redruth, Alberante and Extensions B3 AREAS Brackenhurst and Extentions 1 & 2, Mayberrypark and Extention 1, Brackendowns and Extensions 1,2,3 & 4 B4 AREAS Meyersdal: Meyersdal (Eco Estate & Nature Estate), Thokoza North (Mpilisweni, Phenduka Section, Basothong Sections and Hostels) B5 AREAS Civic Centre and CBD area, Alberton North and Extentions, Parklands Area, Florentia and Extentions, Verwoerd Park and Extentions Brackendowns 5, Albertsdal , Thokoza South (Ext 1 & 2), Thokoza Gardens, Everest, Unit F, Vergenoeg, Edenpark & Extentions, Greenfields, PholaPark & Extentions, B6 AREAS Thinasonke Please take Consumers may be affected by load shedding as per schedule above depending on how much load must be shed. -

Profile: City of Ekurhuleni

2 PROFILE: CITY OF EKURHULENI PROFILE: CITY OF EKURHULENI 3 CONTENT 1. Executive Summary ........................................................................................... 5 2. Introduction: Brief Overview............................................................................. 6 2.1 Historical Perspective ............................................................................................... 6 2.1 Location ................................................................................................................... 7 2.2. Spatial Integration ................................................................................................. 8 3. Social Development Profile............................................................................... 9 3.1 Key Social Demographics ........................................................................................ 9 3.2 Health Profile .......................................................................................................... 12 3.3 COVID-19 .............................................................................................................. 13 3.4 Poverty Dimensions ............................................................................................... 15 3.4.1 Distribution .......................................................................................................... 15 3.4.2 Inequality ............................................................................................................. 16 3.4.3 Employment/Unemployment -

Gauteng Germiston South Sheriff Service Area of Ekurhuleni Central Magisterial District Germiston South Sheriff Service Area Of

!C ! ^ ! !C ^ ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !C ! ! ! ! !C ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !C ! ! ! ! ! !C ! ! ! ! ! ^ ! !C ! ! $ ^ ! ! !C ! ^ ! !C !C ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !C ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !C !C ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !C ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !C !ñ ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ^ ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !C ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ^ ! ! ! !C ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ^ ! !C ! $ ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !C! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !C ! ! ! !C ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !C ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !C ! ! ! !C ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !C ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !C ! ! ! ! ! ! !C ! !C $ ! ! ^ ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !C ! ! !C ! ! ! ! ! !C ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !. ! ^ ! !C ñ ! ! ! ! ! ! ^ ! ^ ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !C !C ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !C ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !C ! ! ! ! !C ! ! !C ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !C ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !C ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ^ ! ! ^ ! ! ^ ! ! ! ^ ! ! ! ! ! !C ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !C ! !C ! ! ^ ! !C ! ! ! ! ñ !C ! !. ! ! ! ! ! ! !C ! ! ! ! ! ! !C ñ !. ! ^ ! ! ! ! ! !C ! !C ! $!C ! ! !. ^ !. ^ ! !C ^ ! ! !C !C ! ! ! !C ! ! !C ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !C ! !C ! !. ^ ! $ ^ !C ! ! !C ^ ! ñ!C !. ! ! !C ^ ! ! !. $ !C !C ! ! ! ! ! ! !C ! !C !. ! ñ ! ! ^ ! !C $ ^ ! ^ ! $ ! ! ! ! !C ! ! ! !C ! ! ! ! ! !C ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ^ ! !C ! !. ñ ! ! ! ^ !C ! ! !C ! ! ! !C !C ! !C ! ! !C !C ! ! !C ! ! ! ! !C ! ! ! ! !C !C ! ^ ! ! $ !C ! !C ! !C !. ^ ! $ ! !C ! ! ! !C !C ! ! -

Gauteng Gauteng Brakpan Sheriff Service Area Brakpan Sheriff

# # !C # # # # # ^ !C # !. ñ!C# # # # !C # $ # # # # # # # # # !C^ # # # # # ^ # # # # ^ !C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C# # # !C!C # # # # # # # # # #!C # # # # !C # # # # # # # !C ^ # # # # # # # # ^ # # # !C # # # # # # # !C # ^ # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # !C # !C # # # # # # # ^ # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # ñ # # # # # # # # # # # # #!C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # !C # # ^ # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # #!C # # # # # # # ^ # # !C # !C # # # # # # # # $ # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # #!C ^ # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C !C # # # # # # # # # # # !C# # ## # # # # !C # # # # # !C# # # ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ^ !C # # # # # # # # ^ # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # ñ # !C # # # # # # !C # # # # !C # # # # # # # !C ## # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # ## # !C # # !C # # # # # # !C # # # !C # ## !C !. # # # # # # # # # # ## # # !C # # # # # # # ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ^ # # # ## # # # # # # # # ñ # # # ^ # !C # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # ## ## # # # # # # # # !C !C# ## # # # # # !C # # # # # # # !C # # # $ # # !C # # !C # # # # !C # # # ^ # # # ^ ## !C # # # !C # #!C # # # # # ñ # # # # # ## # # # !C## # # # # # # # -

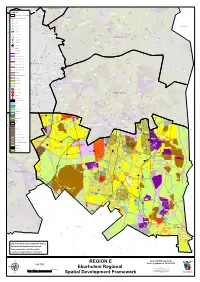

REGION E Ekurhuleni Regional Spatial Development Framework

D R T N ASTON MANOR E TR M NIMROD PARK S J K A U W V O R K N R E G I O N B L A 6 1 R E G I O N B N IL R 8 P O R W A I 2 W M EB H E 1 V EC E BREDELL AH R 3 K IG K D R H 6 D T 8 W R GLEN MARAIS H A T A S KEMPTON PARK V T E T T KEMPTON PARK AH L B D E IR N C A R H R D D R Legend U BENONI AH D P POMONA ESTATES AH D E GORDONS VIEW AH R E ETWATWA K N 8 N 1 O 6 Z T K C 5 S O R O D T N 5 Urban Managment Regional Boundaries N R R S N L T Y VO ON A E OR G L R TR STR N TR ESTHERPARK E G O S KKE T D R I G L ST A O LILYVALE AH R IG S N AR R2 T E M AL AVE 1 R QU ENTR EE L C NSB RD UR G Urban Development Boundary Y R RN S 0 D CO M K 9 A A 6 L K 8 M L 3 D 2 AS R S HOM T T NORTONS HOME ESTATES AH ï R K6 ILE RD G 8 CEC S E P L BRESWOL AH 5 Airport O D o 8 K 1 R K E D N I 6 1 D T BENONI ORCHARDS AH R V 1 1 H A K S H N R K R V 9 T O E 6 U R A E R S H W D D 9 Y V T Y H L E E G G S V BENONI SMALL FARMS S I P POMONA L R S N I S I H S S N A K T O R JATNIEL T T S R E S W N SLATERVILLE AH R H T Cemetery A C R S SPARTAN ïR H D T Y R T T I K BENONI NORTH AH K VALKHOOGTE SHANGRI-LA AH 1 OX RD ENN RD 0 L PITTS v® HoRsHpODitEaSFlIELD 9 FAIRLEAD AH INGLETHORPE AH PUTFONTEIN AH D E L M A S K RD D 1 D R G BONAEROPARK SA I R 0 A L U I S O P B A L E 5 R I R D R R D K O R D O MAYFIELD T R I N N S I R T T W I A 1 N N N E G ï E S T E N L 5 E O S Landfill SiOte 5 D T R 6 E L S ? N 7 R S P R S I R R 8 E L 5 E D R T O I W T A S R K S 1 S N V T 7 E N L O R K L A 3 1 N E D T 3 R E V N A V 7 ISANDO B H 1 C E K A CARO NOME AH W R NDR d M E G Logistics Hub REYV P E ENSTEY E LEK N -

Ekurhuleni Metropolitan Municipality Urban Settlements Development Grant

EKURHULENI METROPOLITAN MUNICIPALITY URBAN SETTLEMENTS DEVELOPMENT GRANT Presentation to Human Settlements Portfolio Committee – 12 Sept 2012 Content 1. Strategic Overview of delivery environment – Key demographic and socio-economic statistics – Services Backlog – Spatial Analysis – Priorities in relation to creation of sustainable Human Settlements 2. BEPP – Budget – Performance Indicators – Risks and challenges 3. USDG Business Plan 2012/13 – Targets & delivery/performance/expenditure 4. Outcome 8 Related Projects: USDG Planning & Delivery 5. Grants Alignment 2 Demographics, social and economic content Key Statistics (2010 estimates) Ekurhuleni Geographic size of the region (sq km) 1928 Population 2,873,997 Population density (number of people per sq km) 1490.72 Economically active population (as % of total population) 48.6 Number of households 909,886 Annual per household income (Rand, current prices) 151,687 Annual per capita income (Rand, current prices) 49,482 Gini coefficient 0.62 Formal sector employment estimates 759,252 3 Demographics, social and economic content Key Statistics (2010 estimates) Ekurhuleni Informal sector employment estimates 93,013 Unemployment rate (expanded definition) 31.1 Percentage of people in poverty 27.5 Poverty gap (R millions) 1,653 Human development index (HDI) 0.65 Index of Buying Power (IBP) 0.08 Total economic output in 2010 (R million at current prices) 137,980 Share of economic output (GVA % of SA in current prices) 6.5 Total economic output in 2010 (R millions at constant 2005 prices) 67,211,143 -

Actonville Wattville Rail Reserve Precinct Plan Draft Jun 2019

DRAFT ACTONVILLE WATTVILLE RAIL RESERVE URBAN DESIGN PRECINCT PLAN Metropolitan Spatial Planning Division City Planning Department City of Ekurhuleni GAPP Consortium Ekurhuleni Urban Design Precinct Plans CONTACT DETAILS CLIENT Metropolitan Spatial Planning Division City Planning Department City of Ekurhuleni tel: +27(0)11-999-4026 email: [email protected] web: www.ekurhuleni.gov.za PROFESSIONAL TEAM GAPP Architects and Urban Designers tel: +27 11 482 1648 email: [email protected] web: www.gapp.net Royal HaskoningDHV tel: email: web: Kayamandi Development Services tel: +27 12 346 4845 email: [email protected] web: www.kayamandi.co.za Submitted: 10 June 2019 2 GAPP Consortium Ekurhuleni Urban Design Precinct Plans TABLE OF CONTENTS 3 REGIONAL OVERVIEW .................................................................... 27 3.1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................ 27 3.2 HISTORIC OVERVIEW OF ACTONVILLE ................................. 27 CONTACT DETAILS .................................................................................. 2 3.3 REGIONAL CONTEXT AND STATUS QUO ............................... 28 3.3.1 Institutional Boundaries ....................................................... 28 TABLE OF CONTENTS ............................................................................. 3 3.3.2 Locality and Accessibility ..................................................... 28 LIST OF DIAGRAMS ................................................................................. -

ALL PUBLIC CERTIFIED ADULT LEARNING CENTRES in GAUTENG Page 1 of 8

DISTRICTS ABET CENTRE CENTRE TEL/ CELL PHYSICAL MUNICIPAL MANAGER ADDRESSES BOUNDARY Gauteng North - D1 / GN Taamane PALC Mr. Dladla D.A. (013) 935 3341 Cnr Buffalo & Gen Louis Bapsfontein, 5th Floor York Cnr. Park Van Jaan, Hlabelela, Zivuseni, 073 342 9798 Botha Baviaanspoort, Building Mandlomsobo, Vezu;wazi, [email protected] Bronkhorstspruit, 8b water Meyer street Mphumelomuhle, Rethabiseng, Clayville, Cullinan, Val de Grace Sizanani, Vezulwazi, Enkangala, GPG Building Madibatlou, Wozanibone, Hammanskraal, Pretoria Kungwini, Zonderwater Prison, Premier Mine, Tel: (012) 324 2071 Baviaanspoort Prison A & B. Rayton, Zonderwater, Mahlenga, Verena. Bekkersdal PALC Mr. Mahlatse Tsatsi Telefax: (011) 414-1952 3506 Mokate Street Gauteng West - D2 / GW Simunye, Venterspost, 082 878 8141 Mohlakeng Van Der Bank, Cnr Human & Boshoff Str. Bekkersdal; Westonaria, [email protected] Randfontein Bekkersdal, Krugersdorp 1740 Zuurbekom, Modderfontein, Brandvlei, Tel: (011) 953 Glenharvie, Mohlakeng, Doringfontein, 1313/1660/4581 Lukhanyo Glenharvie, Mosupatsela High Hekpoort, Kagiso PALC Mr. Motsomi J. M. (011) 410-1031 School Krugersdorp, Azaadville, Azaadville Sub, Fax(011) 410-9258 9080 Sebenzisa Drive Libanon, Khaselihle, Maloney’s Eye, 082 552 6304 Kagiso 2 Maanhaarrand, Silverfields, Sizwile, Sizwile 073 133 4391 Magaliesberg, Sub, Tsholetsega, [email protected] Mohlakeng, Tsholetsega Sub, Khaselihle Muldersdrift, Sub, Silverfieds Sub, Oberholzer, Munsieville. Randfontein, Randfontein South,The Village, Toekomsrus, Khutsong/ Motebong PALC Mr. S. F. Moleko fax:018 7830001 Venterspos, Mohlakeng, Badirile, 082 553 9580 3967 Nxumalo Road Western Areas, ALL PUBLIC CERTIFIED ADULT LEARNING CENTRES IN GAUTENG Page 1 of 8 Toekomsrus, Zenzele. Wedela, Telefax: (018) 788-5180 Khutsong Westonaria, 076 709 0469 Azaadville, Lebanon [email protected] Wedela/ Fochville PALC MS. A.Senoamadi Wedela, Sediegile Fax: (018) 780 1397 363 Ben Shibure 078 6155390 Avenue Kokosi Fochville Tshwane North - D3 / TN Gaerobe PALC Mr. -

Day 2 : Approaches to NDPG Projects Tshiwo Yenana 30 October 2007

TTTTRRII Training for Township Renewal Initiative Day 2 : Approaches to NDPG Projects Tshiwo Yenana 30 October 2007 TTTTRRII Training for Township Renewal Initiative • TTTTRRII Training for Township Renewal Initiative Most people live - whether physically or morally – in a very restricted circle of their potential being. We all have reservoirs of life to draw upon of which we do not dream... William James TTTTRRII Training for Township Renewal Initiative TTTTRRII Training for Township Renewal Initiative Township realities ¾60+% population in townships ¾Unemployment 50+% in townships ¾75+% leakage of local buying power ¾Private sector investment very low ¾Under-performing residential property markets TTTTRRII Training for Township Renewal Initiative • Something needs to be done! • We must dream bigger! • Have a broader vision! TTTTRRII Training for Township Renewal Initiative Overall NDP Approach • Programme Goals • Evaluation Criteria • Funding Allocation • Round 1, 2, 3 & (4) TTTTRRII Training for Township Renewal Initiative Project Locations Round 1 and 2 TTTTRRII TrainingTypes for Township of Renewal Projects Initiative 1. High Street TTTTRRII Training for Township Renewal Initiative Types of Project 2. Nodal TTTTRRII Training for Township Renewal Initiative Types of Project 3. Public Transport TTTTRRII Training for Township Renewal Initiative NDP Unit Project Examples • Njoli • Ngangelizwe • Vilakazi Precinct • Orlando Ekhaya • Monwabisi • Ndwedwe • Bridge City TTTTRRII Training for Township Renewal Initiative NDPG Projects Ref Township -

311 30-10-2013 Gautliquor

T E U N A G THE PROVINCE OF G DIE PROVINSIE UNITY DIVERSITY GAUTENG P IN GAUTENG R T O N V E IN M C RN IAL GOVE Provincial Gazette Extraordinary Buitengewone Provinsiale Koerant Selling price . Verkoopprys: R2,50 Other countries . Buitelands: R3,25 OCTOBER Vol. 19 PRETORIA, 30 2013 OKTOBER No. 311 We oil hawm he power to preftvent kllDc AIDS HEIRINE 0800 012 322 DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH Prevention is the cure N.B. The Government Printing Works will not be held responsible for the quality of “Hard Copies” or “Electronic Files” submitted for publication purposes 305363—A 311—1 2 No. 311 PROVINCIAL GAZETTE EXTRAORDINARY, 30 OCTOBER 2013 ANNUAL PRICE INCREASE FOR PUBLICATION OF A LIQUOR LICENCE: FOR THE FOLLOWING PROVINCES: (AS FROM 1 MAY 2013) GAUTENG LIQUOR LICENCES: R197.90. NORTHERN CAPE LIQUOR LICENCES: R197.90. ALL OTHER PROVINCES: R120.60. CONTENTS • INHOUD Page Gazette No. No. No. GENERAL NOTICE 3025 Gauteng Liquor Act (2/2003): Applications for liquor licences in terms of section 24: Divided into the following regions: ................................................... Johannesburg ......................................................................................................................................................... 5 311 Tshwane.................................................................................................................................................................. 16 311 Ekurhuleni.............................................................................................................................................................. -

Venue Listing

Venue Listing Province : GAUTENG Region : ALL REGIONS Municipality : EKU - EKURHULENI [EAST RAND] Ward : ALL WARDS VD Number : ALL VOTING DISTRICTS VS Status : ACTIVE VS Category : ALL VS CATEGORIES VS Type : ALL VS TYPES VS/VC : ALL VS AND VC Ward VS Name VS VS Type Status Address Stopping Category Times 79700023 LADY FATIMA CHURCH CHURCH (P-VC) ACTIVE 25 VAN WYK STR, BRENTWOOD PARK, N/A 79700023 LADY FATIMA CHURCH HALL PARTITION 1 SUB- (P-SS) ACTIVE 25BENONI VAN WYK STR, BRENTWOOD PARK, N/A 79700023 LADY FATIMA CHURCH HALL PARTITION 2 SUB-STATION (P-SS) ACTIVE 25BENONI VAN WYK STR, BRENTWOOD PARK, N/A 79700024 MUSIC ACADEMY OF GAUTENG SCHOOLSTATION (P-VS) ACTIVE OUTTFONTEINBENONI RD, CLOVERDENE, BENONI N/A 79700024 CRYSTAL PARK HEALTH CLINIC CLINICHALL (P-VC) ACTIVE STRAND STREET, CRYSTAL PARK, BENONI N/A 79700024 CRYSTAL PARK HEALTH CLINIC SUB- (P-SS) ACTIVE STRAND STREET, CRYSTAL PARK, BENONI N/A 79700024 CRYSTAL PARK HEALTH CLINIC TENT 1 SUB-STATION (T-SS) ACTIVE STRAND STREET, CRYSTAL PARK, BENONI N/A 79700024 STARSUN COMPLEX CENTRESTATION (P-VC) ACTIVE 28 C/O BENONI ROAD AND ESTATE ROA, N/A 79700024 STARSUN COMPLEX HALL SUB- (P-SS) ACTIVE 28SMALL C/O BENONIFARM, BENONI ROAD AND ESTATE ROA, N/A 79700024 STARSUN COMPLEX TENT 1 SUB-STATION (T-SS) ACTIVE 28SMALL C/O BENONIFARM, BENONI ROAD AND ESTATE ROA, N/A 79700024 BENONI COUNCIL FOR THE CARE OF THE AGED OLDSTATION AGE (P-VC) ACTIVE PARKERSMALL FARM, ST., RYNFIELD, BENONI BENONI N/A 79700024 BENONI COUNCIL FOR THE CARE OF THE AGED SUB-HOME (P-SS) ACTIVE PARKER ST., RYNFIELD, BENONI