Of Student Teaching in United States Colleges and Universities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MICC Government Purchase Card Program Efforts Earn DOD Recognition

FORT SAM HOUSTON JBSA HOTLINES DOD Safe Helpline 877-995-5247 SEPTEMBER 2, 2016 JBSA Sexual Assault Hotline VOL. 58, NO. 35 808-SARC (7272) JBSA Domestic Abuse Hotline 367-1213 A PUBLICATION OF THE 502nd AIR BASE WING – JOINT BASE SAN ANTONIO-FORT SAM HOUSTON JBSA Duty Chaplain 221-9363 ARNORTH CHANGE OF COMMAND Lt. Gen. Jeffrey S. Buchanan addresses U.S. Army North military members, family, friends and distinguished guests after assuming com- mand of ARNORTH during the change NMETC COLLECTS BACKPACKS FOR KIDS PAGE 3 of command cer- emony at the Fort Sam Houston Quadrangle Friday. For article and more photos, turn to pages 10-11. Photo by Sgt. 1st Class Wynn Hoke MICC Government Purchase Card BAMC COMMANDER HOLDS TOWN HALLS PAGE 6 program efforts earn DOD recognition By Daniel P. Elkins 2015 efforts during the General ing offices, 31 Army command MICC Public Affairs Office Services Administration SmartPay customers, 12 GPC Level-3 Training Forum in Washington, hierarchies, more than 12,000 A Government Purchase Card D.C., Aug. 2-6. Sumpter is the cardholder accounts and program officer at Fort Sam deputy director for program de- approximately $750 million in Houston was recognized earlier this velopment and implementation for annual spending. month by officials from the office defense procurement and acqui- “The fact that you were able to of the undersecretary of defense sition policy at the office of the maintain MICC GPC operations and for acquisition, technology and undersecretary of defense. improve overall program perfor- logistics for improving program Sumpter underscored the size mance … despite the departures of performance while greatly reducing and scope of the Mission and the MICC GPC chief and a business delinquencies command-wide. -

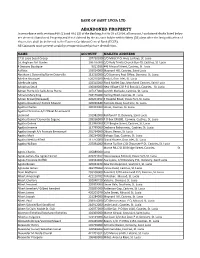

Abandoned Property

BANK OF SAINT LUCIA LTD ABANDONED PROPERTY In accordance with sections#60 (1) and #61 (3) of the Banking Act No 34 of 2006, all account / unclaimed drafts listed below are deemed Abandoned Property and if not claimed by the account holder within thirty (30) days after the last publication of this notice, shall be delivered to the Eastern Caribbean Central Bank (ECCB). All Claimants must present a valid government issued picture identifiction. NAME ACCOUNT MAILING ADDRESS 17 St Lucia Scout Group 107730100 C/O Millet P O, Anse La Raye, St. Lucia 1st Anglican Girl Guides 106756000 C/O Holy Trinity Church Box 40, Castries, St. Lucia 4 Seasons Boutique 9011306 #46 Micoud Street, Castries, St. Lucia A Altius 103014000 Maynard Hill, Castries, Saint Lucia Abraham L Deterville/Karim Deterville 113220000 C/O Dennery Post Office, Dennery, St. Lucia Adeline Bousquet 520210200 Reduit, Gros Islet, St. Lucia Adeltrude Jules 102310000 Black Mallet Gap, Marchand Castries, Saint Lucia Adolphus Small 106049000 New Village C/O P O Box 411, Castries, St. Lucia Adrian Pierre A/c Sally Anne Pierre 107147000 Corinth Marisule, Castries, St. Lucia Adriana Mary King 204126000 Darling Road, Castries, St. Lucia Adrien Brown(Deceased) 420201252 6 Hospital Road, Vieux Fort, St. Lucia Agatha Beaubrun/ Patrick Edward 320026640 Palmiste Road, Soufriere, St. Lucia Agatha Charles 120053000 Union, Castries, St. Lucia Agatha Christmas A/c O'Neal & Leniworth Lesmond 101982000 Richfond P O, Dennery, Saint Lucia Agatha Daniel/ Clementia Eugene 209268000 P O Box CP6091, Conway, Castries, St. Lucia Agatha Delima 212990000 31 F Broglie Street, Castries, St. Lucia Agatha Jeremie 117799000 Desbarra Babonneau, Castries, St. -

Grand Opening for Missouri River Bridge at Rulo

Mound City Published & Printed in Mound City, Missouri Vol. 134, No. 8 75¢ NEWS www.moundcitynews.com Thursday • August 29 • 201 3 A look inside... Rulo Bridge - Out with the old - Early deadline in with the new...........Page 8 for Sept. 5 -------------------- issue Graham Street Fair..............Page 6 There will be an early -------------------- deadline for the September 5, New antique store on State Street 2013, issue of the Mound City in Mound City.........Page 14 News. Due to the Labor Day -------------------- observance on Monday, Sep- tember 2, advertising, news CommuniTEE Golf Benefit raises and photo material are being over $62,000..........Page 9 requested no later than Friday, -------------------- August 30, for the September Squaw Creek Diner to open....Page 14 5 edition. The Mound City News of- -------------------- fice will be closed on Labor Holt County Autumn Festival starting Day, but will reopen for regu- up next week..........Page 7 lar hours on Tuesday, Septem- ber 3, 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. The Maitland, MO, Opera House - Was completely destroyed by fire on Saturday, Midwest Data August 24. The Maitland Rural Fire Department was called to the scene shortly after “Welcome to the Jungle” is theme 7 a.m. Assistance was given by Graham, Skidmore and Mound City fire departments to host customer as well as Maryville Public Safety. for Holt County Autumn Festival appreciation day Holt County residents are in- dents of Holt County; and there vited to get “jungle fever” next is a division that hosts grandchil- September 5 Fire destroys Opera House week during the 61st annual dren of residents of Holt County. -

Independent Study Units: Their Effectiveness in Preparing Cooperating Teachers for Supervisory Responsibility

71-22,510 MILLER, Sandra Waggett, 1940- INDEPENDENT STUDY UNITS: THEIR EFFECTIVENESS IN PREPARING COOPERATING TEACHERS FOR SUPERVISORY RESPONSIBILITY. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1971 Education, teacher training University Microfilms, A XEROX Company, Ann Arbor, Michigan © 1971 SANDRA WAGGETT MILLER ALL RIGHTS RESERVED THIS DISSERTATION HAS BEEN MICROFILMED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED INDEPENDENT STUDY UNITS: THEIR EFFECTIVENESS IN PREPARING COOPERATING TEACHERS FOR SUPERVISORY RESPONSIBILITY DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Sandra Waggett Miller, B.S., M.S. * * # # * The Ohio State University 1971 Approved by Adviser School of Home Economics ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Grateful acknowledgment is made to Dr. Marie M. Dirks, my major advisor, Professor and Chairman of the Division of Home Economics Education, for her cooperation, patience, and positive attitude through out the planning, administration, and writing of this study. Deep appreciation is expressed to all who in any way assisted with the study, and particularly to the following people: my committee members. Dr. Julia I. Dalrymple, Professor in Home Economics Education; Dr. L. 0. Andrews, Professor in Teacher Education; and Dr. Willard H. Wolf, Professor in Agriculture Education, for guidance in planning the study, for reading the dissertation and offering suggestions; the panel members, Miss Janet Fentress, Mrs. Lillie Glover, and Miss Mary Lou Thomas, who so graciously critiqued the conference tapes; the cooperating and student teachers for so kindly providing the research data; and my husband, whose convictions about higher education provided the initial inspiration for me to pursue the doctoral program. -

HAM-75-10.10 Thru the Valley 07-19-06 Public Meeting MASTER MAILING LIST

HAM-75-10.10 Thru the Valley 07-19-06 Public Meeting MASTER MAILING LIST ContactName Mailing Address CSZ 300 E Business Way Cincinnati, OH 45241 312 Davis St Cincinnati, OH 45215 209 Davis St Cincinnati, OH 45215 508 Pike St Cincinnati, OH 45215 PO Box 15771 Cincinnati, OH 45215 Mr. Thomas Abbott 3460 Cooper Rd Cincinnati, OH 45241 Khadijah Abdurrahman 10136 Hunter Ct Cincinnati, OH 45215 Ms. Jackie Abernathy 8005 Stillwell Rd Cincinnati, OH 45237 Mr. Douglas Abney 614 Arlington Ave Cincinnati, OH 45215 Ms. Angela Abrams 328 Central Ave Cincinnati, OH 45215 Renee Ackman 8237 Anthony Wayne Ave Cincinnati, OH 45216 Ms. Janet Acus 104 Pershing Ave Cincinnati, OH 45215 Mr. Charles Adams 441 Hillside Ave Cincinnati, OH 45215 Mr. Scott Adams 225 W Court St Cincinnati, OH 45202 Kelly Adkins 560 Maple Ave Cincinnati, OH 45215 Terry Adkins 248 N Cooper Ave Cincinnati, OH 45215 Ba Adma 8356 Anthony Wayne Ave Cincinnati, OH 45216 Mr. Richard Agee 410 Arlington Ave Cincinnati, OH 45215 Mr. John Ahern, IV 637 E Sharon Rd Cincinnati, OH 45246 Ms. Ruby Aker 423 Arlington Ave Cincinnati, OH 45215 Ms. Tiffany Albright 1405 Adams St Cincinnati, OH 45215 Ms. Kathleen Albrinck 434 Pearl St Cincinnati, OH 45215 Mr. Edward Alcorn 101 Home Ave Cincinnati, OH 45215 Mr. James Alcorn 300 N Cooper Ave Cincinnati, OH 45215 Ms. Tina Alcorn 1111 Market St. Reading, OH 45215 Mr. Jesse Alexander 7858 Dawn Rd Cincinnati, OH 45237 Mr. Floyd Allateef 1270 Chamberlain Ave Cincinnati, OH 45215 Ms. Rica Allen 8359 Anthony Wayne Ave Cincinnati, OH 45216 Mr. -

Driver Blamed in Crash

Safety measures Shift the job Maryland, 5 other states to Commission wants public defender’s launch Ebola monitoring for travelers. 3A office to handle lawyers-at-bail load. 10A Thursday, October 23, 2014 Volume 126 | Number 015 TheDailyRecord.com Driver Longshot candidate at liberty to speak freely blamed Libertarian Dymowski uses campaign for AG to challenge drug laws in crash NTSB: Derailment, spill caused by truck operator who was distracted BY BRYAN P. SEARS [email protected] A 2013 train derailment and explo- sion in Rosedale was the result of a dis- tracted truck driver who failed to ensure that the tracks were clear before attempting to cross, according to a re- port released by the National Trans- portation Safety Board. A nearly year-long investigation by the federal agency found that the May 2013 collision between a CSX train car- rying chemicals and a trash truck was caused by driver negligence. As a result, the board is recommend- MAXIMILIAN FRANZ ing a prohibition on the use of hands- ‘The system now just doesn’t work,’ Leo Wayne Dymowski says of the current laws criminalizing nonviolent drug offenses. ‘We can’t jail free cellphone devices while operating ourselves out of the problem.’ commercial vehicles, according to the BY STEVE LASH cer for the Maryland Parole Commis- report. [email protected] sion. “Current laws may mislead people to “The system now just doesn’t believe that hands-free is as safe as not Libertarian Leo Wayne Dymowski work,” he said. “We can’t jail ourselves using a phone at all,’’ Acting Chairman says he knows he has little chance for out of the problem.” Christopher A. -

The C Club Mado Onna a Bam Mbooz

MIAMI MIRROR – TRUE REFLECTIONS Club Madonna THE CLUB MADONNA BAMBOOZLE the Hoodwinking of Leroy Griffith Page 1 of 43 MIAMI MIRROR – TRUE REFLECTIONS By David Arthur Walters August 12, 2013 Word was out on South Beach’s Washington Avenue this Spring that Leroy Griffith, owner of the totally nude strip joint, Club Madonna, was about to bring a fraud suit against the City of Miami Beach, City Attorney Jose Smith, former Mayor David Dermer, former Commissioners Simon Cruz and Saul Gross, and former city attorneys Gary Held and Murray Dubbin. Furthermore, it was joyfully proclaimed, Griffith planned to expose Mayor Matti Bower and Commissioner Deede Weithorn for promising they would help him get a liquor license in return for $4,000 in campaign contributions. Members of the family of city officials sued by Club Madonna Most people are surprised and patrons of the naked arts disappointed that Club Madonna cannot sell liquor simply because its entertainers appear totally nude, although alcohol may be served in partially nude clubs where private parts are left to an imagination that can be more provocative than the real thing. Sally Rand in Bubble Dancer Recall that the great burlesque dancer Sally Rand was arrested multiple times for indecent exposure although her nudity was only imagined; a San Francisco judge who viewed her performance said that anyone who thought it was lewd had a perverse notion of morals. Page 2 of 43 MIAMI MIRROR – TRUE REFLECTIONS Nude clubs elsewhere can sell liquor, so what in the world is wrong with the City of Miami Beach? Meyer Lansky must be spinning in the grave at the sight of the sunny city exercising a legalized monopoly on pursuits better left to illegally organized crime! Maybe not: Griffith reportedly sued Charlotte, North Carolina, television station WBTV and Fayetteville police Capt. -

Descendants of Brownlee Johnston (1812-1874)

Descendants of Brownlee Johnston (1812-1874) In this record, persons are numbered consecutively. If they married and are known to have children, there is a plus sign (+) in front of their name, which indicates that additional information about them can be found in the next generation. I am solely responsible for all errors in this record. Corrections and additions are appreciated. Stephen W. Johnson 222 Parkman Ave. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15213 [email protected] July 26, 2019 Descendants of Brownlee Johnston 26 July 2019 First Generation 1. Unknown JOHNSTON was born (date unknown). Elizabeth UNKNOWN was born in 1773 in Maryland. This according to the 1850 Census, which shows an an Elizabeth Johnston, age 77 and born in Maryland, to be living with Brownlee Johnston in the Third Ward of the City of Pittsburgh. Elizabeth is presumed to be Brownlee's mother. Unknown JOHNSTON and Elizabeth UNKNOWN had the following child: +2 i. Brownlee JOHNSTON, born December 16, 1812, Ohio; married Eliza Ann RAE OR REA OR RAY, March 24, 1840, Pittsburgh, Allegheny Co., Pennsylvania; died November 28, 1874, West Wheatfield Twp., Indiana County, Pennsylvania. Second Generation 2. Brownlee JOHNSTON was born on December 16, 1812 in Ohio. He died on November 28, 1874 at the age of 61 in West Wheatfield Twp., Indiana County, Pennsylvania. According to a handwritten "Family Record", probably from a family Bible, obtained from Emma Johnson Farmin: 1. Brownlee was born on December 16, 1812, 2. Brownlee died November 28, 1874, and and 3. Brownlee and Eliza Ann Ray were married on March 24, 1840. This source is believed to be generally accurate and will be relied upon unless other sources require a different conclusion. -

An Assessment of the Effects of Two Experimental Arrangements on the Classroom Behavior of Student Teachers As Measured by IOTA

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 053 073 SP 005 031 AUTHOR Kelly, Donald Edward TITLE An Assessment of the Effects of Two Experimental Arrangements on the Classroom Behavior of Student Teachers as Measured By IOTA. INSTITUTION Arizona State Univ., Tempe. PUB DATE Sep 70 NOTE 158p.; Doctoral dissertation presented at Arizona State University, 1970 EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF-$0.65 HC-$6.58 DESCRIPTORS Classroom Observation Techniques, *Effective Teaching, *Field Experience Programs, *Preservice Education, *Program Effectiveness, *Secondary School Teachers, Student Teachers, Teacher Behavior ABSTRACT This study found no significant difference in classroom teaching performance between participants enrolled in the three semester on-site teacher preparation sequence and participants enrolled in a one semester on-campus and two semester on-site sequence. Subjects were 39 volunteer undergraduate students enrolled in the Department of Secondary Education at Arizona State University, randomly assigned to two experimental groups. Group A spent three semesters in on-site experiences which included observation/participation activities and weekly on-site seminars. Participation activities were increased throughout the program. Group B spent the first semester in on-campus activities which included seminars, microteaching, using audiovisual materials, group dynamics, set induction theory, lesson plans, and interaction analysis. Group B's second and third semester experiences paralleled those of Group A. During the last semester, two 45-minute live classroow observations were made on each participant using the Instrument for the Observation of Teaching Activities (IOTA). Data were analyzed by computing t ratios for each of the 14 observation scales based on the mean scores of the two observations. Since there was no difference in performance between the groups, it was recommended that Sequence B be adopted for logistical reasons, and that a longitudinal follow-up study be conducted on participants. -

Commencement1989.Pdf (7.320Mb)

TheJohns Hopkins University Conferring of Degrees At the Close of the 1 13th Academic Year May 25, 1989 Contents Order of Procession 1 Order of Events 2 Honorary Degree Citations 10 Academic Regalia 14 Awards 16 Honor Societies 21 Student Honors 24 Degree Candidates 26 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from LYRASIS Members and Sloan Foundation http://archive.org/details/commencement1989 Order Of Procession MARSHALS Marc D. Donohue Richard A. Macksey Bruce R. Eicher Marion C. Panyan Bruce R. Ellingwood Charles S. Pearson Joseph Hugh Ellis Peter B. Petersen Lawrence Grossman A.J. R. Russell-Wood John W. Gryder Henry M. Seidel Lynn Taylor Hebden Stella Shiber THE GRADUATES MARSHALS Warner E. Love Moshe Rosen THE FACULTIES MARSHALS Carl F. Christ Charles Roger Westgate THE DEANS OFFICERS OF THE UNIVERSITY THE TRUSTEES CHIEF MARSHAL I. William Zartman THE CHAPLAINS THE PRESENTERS OF THE HONORARY DEGREE CANDIDATES THE HONORARY DEGREE CANDIDATES THE PROVOST OF THE UNIVERSITY THE CHAIRMAN OF THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES THE PRESIDENT OF THE UNIVERSITY Order Of Even i s STEVEN MULER r President oj the I niversity, presiding Prki.i in Suite from the American Brass Band Journal G.W.E. Friederich (1821-1885) Suite from Funff—stimmigte blasenda Music JohannPezel (1639-1694) Processional The audience is requested to stand as the Academic Procession moves into the area and to remain standing after the Invocation Festival Marches from "Belshazzar, Flioridante, Ezio, Saint Cecilia's Day, Rinaldo, Scipione and Judas Maccabaeus" Georg Friedrich Handel 1 (1685-1759) The President's Procession Fanfare Walter Piston (1894-1976) Grand Entree from "Alceste" Georg Friedrich Handel '(1685-1759) —2— * Invocation CLYDE R. -

Gabriel Jones Izard Family

Gabriel Jones Izard Gabriel Jones Izard, b. 6 Jan 1813, KY, d. c. 1866, Fayette County, TX, married c. 1832, St. Francis County, AR, Macy Tyer, b. 3 Apr 1814, MO, d. 3 May 1898, Coryell, County, TX (1850 St. Francis County, AR, census; 1860, 1870 and 1880 Fayette County, TX, censuses; “The Izards,” by Julia I. Hemenway) Gabriel J. Izard and Macy Tyer had the following children: 1. Silas Calvin Izard b. c. 1834, St. Francis County, AR (1850 St. Francis County, AR, census; 1860 Fayette County, TX, census) d. 14 Dec 1862, Granada County, MS (NARA Confederate Service Record) 2. Mary Catherine Izard b. 25 Sep 1836, St. Francis County, AR (1840 St. Francis County, AR, census; “The Izards,” by Julia I. Hemenway) d. 25 Aug 1846, St. Francis County, AR (1850 St. Francis County, AR, census; “The Izards,” by Julia I. Hemenway) 3. Elizabeth Jane Izard b. c. 1838, St. Francis County, AR (1850 St. Francis County, AR, census; “The Izards,” by Julia I. Hemenway) d. 27 Apr 1888, TX (“The Izards,” by Julia I. Hemenway) m. 29 Nov 1859, Fayette County, TX, Abraham Conn McCown, b. c. Mar 1833, TN, d. 24 Feb 1928, Wilson County, TX. Abraham C. McCown remarried 10 Jan 1889, TX. No 1870 census record has been found for Abraham C. McCown and Elizabeth J. Izard (1860 and 1880 Lavaca County, TX, censuses; 1900 and 1920 Wilson County, TX, censuses; Texas Marriages, 1851-1900; Texas Death Index, 1903-2000) Abraham C. McCown and Elizabeth J. Izard had the following children: John William McCown b. -

Black Alumni Society Membership Matters

Presented By BLACK ALUMNI SOCIETY MEMBERSHIP MATTERS Become a proud member of the Arkansas Alumni Association at join.arkansasalumni.org for exclusive member perks and the latest news on all Arkansas Alumni events happening on The Hill and around the globe. Get involved with societies like the Black Alumni Society or stay connected virtually and in person by joining your local alumni chapter. There are 25+ chapters across the nation! Follow us on Facebook, Twitter or Instagram: @ArkansasAlumni. Table of Contents Foreword: Letter from the Chancellor ...................................................................................................... 3 Connect Engage Inspire BAS President.................................................................................................... 5 Foreword: Letter from the Provost ............................................................................................................ 6 Foreword: Letter from the Vice Chancellor for Diversity, Equity and Inclusion ................................ 7 Welcome - Associate Vice Chancellor and Executive Director ............................................................. 8 Welcome - Letter from the Arkansas Alumni Board of Directors ........................................................ 9 Sponsors ...................................................................................................................................................... 10 Mission & Purpose ...................................................................................................................................