Ed 070 119 Author Title Pub Date Note Edrs Price

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Societe Canadienne Pour Les Traditions Musicales

50 51 CONSEIL Bulletin editor) Heather Sparling, 128-833 Scollard Res.: (416) 225-1547 Court, Mississauga, Ont. L5V 2B4 D'ADMINISTRATION/ Email: [email protected] Res.: (905) 501-1459 BOARD OF DIRECTORS Email: [email protected] Maureen Chafe,4512 Charleswood Dr. NW, Calgary, Alta. T2L 2E3 Norman Stanfield, 301 2017 West 5 Ave., Res.: (403) 277-7908; Bus.: 240-8984; Fax: Vancouver, B.C. V6J 1P8 Presidente/President 240-6594(must be addressed to Res. & bus.: (604) 732-6404 Maureen Chafe) Leslie Hall, Dept. of Philosophy & Email: [email protected] Music, Ryerson Polytechnic University, Email: [email protected] 350 Victoria St., Toronto, Ont. Phil Thomas, 4158 West 10th Ave., Anne-Marie Desdouits, Universite M4G 2K3 . Vancouver, B.C. V6R 2H3 Laval, Ethnologie, Departement 21 Berney Cres., Toronto, Ont. Res.: (604) 224-4678 d'histoire, Faculte de lettres, Pavilion M4G 3G4 Email: [email protected] Res.: (416) 485-4545; Bus.: 979-5000, ext. de Koninck, Ste-Foy (Quebec) G1V 7P4 (no attachments) or 7044; Fax: 979-5362 2517, rue Des Plaines, Ste-Foy (Quebec) [email protected] Email: [email protected] G1V 1B2 Res.: (418) 652-8225; Bus.: 656-2131, ext. David Warren, 103 Old Forest Hill Rd., SOCIETE Vice-presidents/Vice-Presidents 7996 Toronto, Ont. M5P 2R8 Email: anne- Res.: (416) 781-3922; Bus.: 763-4183; Fax: CANADIENNE Mike Ballantyne, P.O.B. 312, Cobble [email protected] 763-1310 Hill, B.C. V0R 1L0 Email: [email protected] Res.: (250) 743-3996 Dave Foster, 1516 24th St. NW, Calgary, POUR LES Email: [email protected] Alta. -

Communicology and Culturology: Semiotic Phenomenological Method in Applied Small Group Research

The Public Journal of Semiotics IV(2), February 2013 71 Communicology and Culturology: Semiotic Phenomenological Method in Applied Small Group Research Richard L. Lanigan1, International Communicology Institute, Washington, D.C., USA Southern Illinois University at Carbondale, Carbondale, Illinois, USA Abstract Communicology is the science of human communication where consciousness is constituted as a medium of communication at four interconnected levels of interaction experience: intrapersonal (embodied), interpersonal (dyadic), group (social), and inter-group (cultural). The focus of the paper is the group level of communication across generations, thus constituting inter-group communication that stabilizes norms (forms a culture). I propose to explicate the way in which the method of semiotic phenomenology informs the pioneering work at the University of Toronto by Tom McFeat, a Harvard trained cultural anthropologist, on small group cultures as an experimental research methodology. Rather than the cognitive- analytic (Husserl‘s transcendental eidetic) techniques suggest by Don Ihde as a pseudo ―experimental phenomenology‖, McFeat provides an applied method for the empirical experimental constitution of culture in conscious experience. Group cultures are constructed in the communicological practices of group formation and transformation by means of a self- generating group narrative (myth) design. McFeat‘s method consists of three steps of culture formation by communication that are: (1) Content-Ordering, (2) Task-Ordering, and (3) Group-Ordering, i.e., what Ernst Cassirer and Karl Jaspers call the logic of culture or Culturology. These steps are compared to the descriptive phenomenology research procedures suggested by Amedeo Giorgi following Husserl‘s approach: (1) Find a sense of the whole, (2) Determine meaning units, (3) Transform the natural attitude expressions into phenomenologically, psychologically sensitive expressions. -

FACTOR 2006-2007 Annual Report

THE FOUNDATION ASSISTING CANADIAN TALENT ON RECORDINGS. 2006 - 2007 ANNUAL REPORT The Foundation Assisting Canadian Talent on Recordings. factor, The Foundation Assisting Canadian Talent on Recordings, was founded in 1982 by chum Limited, Moffat Communications and Rogers Broadcasting Limited; in conjunction with the Canadian Independent Record Producers Association (cirpa) and the Canadian Music Publishers Association (cmpa). Standard Broadcasting merged its Canadian Talent Library (ctl) development fund with factor’s in 1985. As a private non-profit organization, factor is dedicated to providing assistance toward the growth and development of the Canadian independent recording industry. The foundation administers the voluntary contributions from sponsoring radio broadcasters as well as two components of the Department of Canadian Heritage’s Canada Music Fund which support the Canadian music industry. factor has been managing federal funds since the inception of the Sound Recording Development Program in 1986 (now known as the Canada Music Fund). Support is provided through various programs which all aid in the development of the industry. The funds assist Canadian recording artists and songwriters in having their material produced, their videos created and support for domestic and international touring and showcasing opportunities as well as providing support for Canadian record labels, distributors, recording studios, video production companies, producers, engineers, directors– all those facets of the infrastructure which must be in place in order for artists and Canadian labels to progress into the international arena. factor started out with an annual budget of $200,000 and is currently providing in excess of $14 million annually to support the Canadian music industry. Canada has an abundance of talent competing nationally and internationally and The Department of Canadian Heritage and factor’s private radio broadcaster sponsors can be very proud that through their generous contributions, they have made a difference in the careers of so many success stories. -

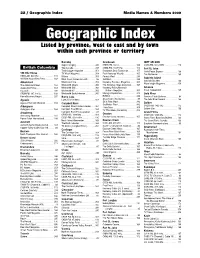

Geographic Index Media Names & Numbers 2009 Geographic Index Listed by Province, West to East and by Town Within Each Province Or Territory

22 / Geographic Index Media Names & Numbers 2009 Geographic Index Listed by province, west to east and by town within each province or territory Burnaby Cranbrook fORT nELSON Super Camping . 345 CHDR-FM, 102.9 . 109 CKRX-FM, 102.3 MHz. 113 British Columbia Tow Canada. 349 CHBZ-FM, 104.7mHz. 112 Fort St. John Truck Logger magazine . 351 Cranbrook Daily Townsman. 155 North Peace Express . 168 100 Mile House TV Week Magazine . 354 East Kootenay Weekly . 165 The Northerner . 169 CKBX-AM, 840 kHz . 111 Waters . 358 Forests West. 289 Gabriola Island 100 Mile House Free Press . 169 West Coast Cablevision Ltd.. 86 GolfWest . 293 Gabriola Sounder . 166 WestCoast Line . 359 Kootenay Business Magazine . 305 Abbotsford WaveLength Magazine . 359 The Abbotsford News. 164 Westworld Alberta . 360 The Kootenay News Advertiser. 167 Abbotsford Times . 164 Westworld (BC) . 360 Kootenay Rocky Mountain Gibsons Cascade . 235 Westworld BC . 360 Visitor’s Magazine . 305 Coast Independent . 165 CFSR-FM, 107.1 mHz . 108 Westworld Saskatchewan. 360 Mining & Exploration . 313 Gold River Home Business Report . 297 Burns Lake RVWest . 338 Conuma Cable Systems . 84 Agassiz Lakes District News. 167 Shaw Cable (Cranbrook) . 85 The Gold River Record . 166 Agassiz/Harrison Observer . 164 Ski & Ride West . 342 Golden Campbell River SnoRiders West . 342 Aldergrove Campbell River Courier-Islander . 164 CKGR-AM, 1400 kHz . 112 Transitions . 350 Golden Star . 166 Aldergrove Star. 164 Campbell River Mirror . 164 TV This Week (Cranbrook) . 352 Armstrong Campbell River TV Association . 83 Grand Forks CFWB-AM, 1490 kHz . 109 Creston CKGF-AM, 1340 kHz. 112 Armstrong Advertiser . 164 Creston Valley Advance. -

Communication History and Its Research Subject1

COMMUNICATION HISTORY AND ITS RESEARCH SUBJECT1 Emanuel KULCZYCKI 2 Abstract: The article proposes a way of defining the research subject of the history of communication. It concentrates on the use of philosophical tools in the study of the collective views of communication practices. The study distinguishes three aspects in the research subject: the means and forms of communication, the collective views of communication practices and communication practices as such. On the theoretical level, these aspects are reflected in various studies undertaken in the fields of media history, the history of the idea of communication and the history of communication practices. The analysis is conducted from a meta-theoretical point of view which places the argument within two orders: that of the research subject and that of the discipline. To give an outline of the current state of research, a distinction is introduced between an implicit and an explicit history of communication. The effect of these considerations is presented in a diagram that specifies the aspects of the research subject as well as the relationships between them. Keywords: communicology, communication practices, reflexive historicizing, communication theory, media. 1. Introduction Scientific research on communication has been undertaken since the first half of the 20th century. Naturally, communication itself, as well as reflection on it, has a much longer history. However, in the pre-scientific studies on what we now call communication, neither the term itself, nor even the notion of communication appears most of the time.3 1 Acknowledgments: I would like to thank Michał Wendland, Mikołaj Domaradzki, Paweł Gałkowski and Stanisław Kandulski for their valuable observations. -

Download the Music Market Access Report Canada

CAAMA PRESENTS canada MARKET ACCESS GUIDE PREPARED BY PREPARED FOR Martin Melhuish Canadian Association for the Advancement of Music and the Arts The Canadian Landscape - Market Overview PAGE 03 01 Geography 03 Population 04 Cultural Diversity 04 Canadian Recorded Music Market PAGE 06 02 Canada’s Heritage 06 Canada’s Wide-Open Spaces 07 The 30 Per Cent Solution 08 Music Culture in Canadian Life 08 The Music of Canada’s First Nations 10 The Birth of the Recording Industry – Canada’s Role 10 LIST: SELECT RECORDING STUDIOS 14 The Indies Emerge 30 Interview: Stuart Johnston, President – CIMA 31 List: SELECT Indie Record Companies & Labels 33 List: Multinational Distributors 42 Canada’s Star System: Juno Canadian Music Hall of Fame Inductees 42 List: SELECT Canadian MUSIC Funding Agencies 43 Media: Radio & Television in Canada PAGE 47 03 List: SELECT Radio Stations IN KEY MARKETS 51 Internet Music Sites in Canada 66 State of the canadian industry 67 LIST: SELECT PUBLICITY & PROMOTION SERVICES 68 MUSIC RETAIL PAGE 73 04 List: SELECT RETAIL CHAIN STORES 74 Interview: Paul Tuch, Director, Nielsen Music Canada 84 2017 Billboard Top Canadian Albums Year-End Chart 86 Copyright and Music Publishing in Canada PAGE 87 05 The Collectors – A History 89 Interview: Vince Degiorgio, BOARD, MUSIC PUBLISHERS CANADA 92 List: SELECT Music Publishers / Rights Management Companies 94 List: Artist / Songwriter Showcases 96 List: Licensing, Lyrics 96 LIST: MUSIC SUPERVISORS / MUSIC CLEARANCE 97 INTERVIEW: ERIC BAPTISTE, SOCAN 98 List: Collection Societies, Performing -

November 6, 2019

Copyright Board Commission du droit d’auteur Canada Canada November 6, 2019 In accordance with section 68.2 of the Copyright Act, the Copyright Board hereby publishes the following proposed tariff: • Commercial Radio Reproduction Tariff (CMRRA, SOCAN, Connect/SOPROQ, and Artisti: 2021-2023) By that same section, the Copyright Board hereby gives notice to any person affected by this proposed tariff that users or their representatives who wish to object to this proposed tariff may file written objections with the Board, at the address indicated below, no later than the 30th day after the day on which the Board published the proposed tariff under paragraph 68.2(a), that is no later than December 6, 2019. Lara Taylor Secretary General Copyright Board Canada 56 Sparks Street, Suite 800 Ottawa, Ontario K1P 5A9 Telephone: 613-952-8624 [email protected] PROPOSED TARIFF filed with the Copyright Board pursuant to subsection 67(1) of the Copyright Act 2019-10-15 CMRRA, SOCAN, Connect/SOPROQ, and Artisti Commercial Radio Reproduction Tariff for the reproduction of musical works by commercial radio stations 2021-01-01 – 2023-12-31 Proposed citation: Commercial Radio Reproduction Tariff (CMRRA, SOCAN, Connect/SOPROQ, and Artisti: 2021-2023) STATEMENT OF ROYALTIES TO BE COLLECTED FROM COMMERCIAL RADIO STATIONS BY THE CANADIAN MU- SICAL REPRODUCTION RIGHTS AGENCY LTD. (CMRRA), AND BY THE SOCIETY OF COMPOSERS, AUTHORS AND MUSIC PUBLISHERS OF CANADA, THE SOCIÉTÉ DU DROIT DE REPRODUCTION DES AUTEURS, COMPOSITEURS ET ÉDITEURS AU CANADA INC. AND SODRAC 2003 INC. (SOCAN), FOR THE REPRODUCTION, IN CANADA, OF MUSICAL WORKS, BY CONNECT MUSIC LICENSING SERVICE INC. -

Communicology, Apparatus, and Post-History: Vilém Flusser's Concepts Applied to Video Games and Gamification

Repositorium für die Medienwissenschaft Fabrizio Poltronieri Communicology, Apparatus, and Post-history: Vilém Flusser’s Concepts Applied to Video Games and Gamification 2014 https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/619 Veröffentlichungsversion / published version Sammelbandbeitrag / collection article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Poltronieri, Fabrizio: Communicology, Apparatus, and Post-history: Vilém Flusser’s Concepts Applied to Video Games and Gamification. In: Mathias Fuchs, Sonia Fizek, Paolo Ruffino u.a. (Hg.): Rethinking Gamification. Lüneburg: meson press 2014, S. 165–186. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/619. Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Creative Commons - This document is made available under a creative commons - Namensnennung - Weitergabe unter gleichen Bedingungen 4.0 Attribution - Share Alike 4.0 License. For more information see: Lizenz zur Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu dieser Lizenz https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0 finden Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0 COMMUNICOLOGY, AppARATUS, AND POST-HISTORY: VILÉM FLUssER’S CONCEPTS AppLIED TO VIDEO GAMES AND GAMIFICATION by Fabrizio Poltronieri Among the philosophers who undertook the task of thinking about the status of culture and the key advents of the twentieth century, the Czech- Brazilian Vilém Flusser deserves prominent recognition. A multifaceted thinker, Flusser produced sophisticated theories about a reality in which man advances towards the game, endorsed by the emer- gence of a kind of technical device that is dedicated, mainly, to the calcula- tion of possibilities and to the projection of these possibilities on reality, gen- erating a veil that conceals the natural reality and creates layers of cultural and artificial realities. -

Introduction

FLUSSER STUDIES 06 1 Introduction The sixth issue of Flusser Studies is the first in a series dedicated to theoretical convergences and divergences between Vilém Flusser’s work and that of other communication theorists and philo- sophers, among them Gilles Deleuze and Jean Baudrillard. We begin with a dialogue between Vilém Flusser and Marshall McLuhan, two of the major, if not the most significant, media and communication theorists of the second half of the 20th century. The issue is also the result of a collaboration between the editors of Flusser Studies and several members of the Visible City Project (www.visiblecity.ca) at York University in Toronto. The VC project, very much inspired by a McLuhanesque framework (i.e., an aesthetic approach to social spaces), investigates how art practices function in specific contemporary urban contexts to educate about and transform the experience of urban dwelling in light of the changing technological, economic and cultural expe- riences of globalization. What is particularly exciting about engaging with theoretical and metho- dological problems in communication and culture through the writings of Flusser and McLuhan is that they were working in very different contexts -- at polar ends, in fact, of the Americas. Consequently, their views of technology, communication, media, and aesthetics are very much a product of these places and of the post-war period. Both Flusser and McLuhan share a distinctive interdisciplinary style of writing that aligns them with a post-war generation of cultural theorists like Raymond Williams, Roland Barthes and Umberto Eco. Their theories exceed academically defined norms of writing and disciplinary boundaries that have contributed to the richness and complexity of humanistic studies (which is not to say that science was beyond their purview). -

SSS 48 1.Indd

146 Johan Siebers Sign Systems Studies 48(1), 2020, 146–158 Philosophy as communication theory Johan Siebers1 Abstract. There has been comparatively little attention for the fundamental ontology of communication in recent philosophy. Nevertheless, from classical metaphysical accounts of relationality and communal being to the analysis of intersubjectivity in phenomenology and to concrete existence as understood by process philosophy, the communicative structure of the act of being has been, if not explicitly then implicitly, a perennial component of metaphysical reflection. Communication theory can be conceived in such a way that it takes this ontological dimension into account. The ramifications of connecting being to communication in this way are explored in discussion with the conceptualizations of communication in integrationism and biosemiotics. An interpretation of Gabriel Marcel’s existential analysis of “my life” is used to show what philosophy as communication theory (in the strong sense of the notion elaborated here) might look like. Keywords: philosophy of being; communication theory; existentialism; process philo- sophy; integrationism; biosemiotics; life It may not be too far-fetched to suggest that integrationism, biosemiotics and philosophy of communication share an idea, perhaps initially not much more than an intuition, about the ubiquity of communication. For integrationists, all being is contextual relating, or what they call sign- making. The integrationist assumes, out of a kind of ontological prudency, that nothing can really be said about other sign-makers than that we know from first-hand experience, namely ourselves. But allowing for that, not insignificant, qualification, communication is a universal ether within which the sign-maker exists, even more intimately infused by it than a fish by the water that it moves around in and that it breathes. -

ED 355 570 ABSTRACT Most of What Communication Scholars Theorize

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 355 570 CS 508 098 AUTHOR Lanigan, Richard L. TITLE Roman Jakobson's Semiotic Theory of Communication. [Revised.] PUB DATE 19 Nov 91 NOTE 10p.; Revised version of a paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Speech Communication Association (77th, Atlanta, GA, October 31-November 3, 1991). PUB TYPE Speeches/Conference Papers (150) Viewpoints (Opinion/Position Papers, Essays, etc.) (120) EDRS PRICE MFO1 /PCO1 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Communication (Thought Transfer); Information Theory; *Language Role; Models; *Semiotics IDENTIFIERS Discourse; *Jakobson (Roman) ABSTRACT For most of the 20th century, Roman Jakobson's name will have been synonymous with the definition of communication as a human science, i.e., communicology. Jakobson is the modern sourceof most of what communication scholars theorize about andpractice as human communication, and he will be the source of howcommunication scholars shall come to understand communication in the future asthe theoretical and applied use of semiotic principles of epistemology. Roman Jakobson alone offers a theory of communication(derived from Jakobson's immediate correction in 1950, on linguistic and semiotic grounds, of an ill-fated information theory) groundedin the study of human language as Aristotle's trivium of an integratedpractice of thought, speech, and inscription, i.e., logic, rhetoric,and grammar, all of which are explicated by a semiotic understandingof what it means to be human. Analysis ofJakobson's model of communication indicates that it is inherently semiotic in origin, rather than linguistic as he himself believed. (A figure representing aspectsof communication theory and information theory is attached.)(RS) *********************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. -

Redalyc.COMMUNICOLOGY: APPROACHING THE

Razón y Palabra ISSN: 1605-4806 [email protected] Universidad de los Hemisferios Ecuador Lanigan, Richard L. COMMUNICOLOGY: APPROACHING THE DISCIPLINE'S CENTENNIAL Razón y Palabra, núm. 72, mayo-julio, 2010 Universidad de los Hemisferios Quito, Ecuador Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=199514906008 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative RAZÓN Y PALABRA Primera Revista Electrónica en América Latina Especializada en Comunicación www.razonypalabra.org.mx COMMUNICOLOGY: APPROACHING THE DISCIPLINE’S CENTENNIAL Richard L. Lanigan1 Abstract Communicology is the science of human communication. The essay tracts the nearly one hundred year development of the concept of communicology into a formal discipline in the human sciences. The chronology of publications begins in the 1920s with the phenomenologist Edmund Husserl and develops up through 2010 with current publications specifying the application of theory and practice in such area as intrapersonal, interpersonal, group, and cultural communicology throughout the world. A focus of this disciplinary development is the foundation in 2000 of the International Communicology Institute. Keywords Communicology, discourse, human science, human communication, semiotics, phenomenology “SEMIÓTICA Y COMUNICOLOGÍA: Historias y propuestas de una mirada científica en construcción” Número 72 RAZÓN Y PALABRA Primera Revista Electrónica en América Latina Especializada en Comunicación www.razonypalabra.org.mx Presentation The human essence of consciousness, and awareness of that consciousness in discourse, is communication in its full semiotic display of verbal and nonverbal codes as the phenomenology of experience.