DARPA's Advanced Logistics Program

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JP 2-03, Geospatial Intelligence in Joint Operations

Joint Publication 2-03 T OF EN TH W E I S E ' L L M H D T E F T E N A R D R A M P Y E • D • U A N C I I T R E E D M S A T F AT E S O Geospatial Intelligence in Joint Operations 5 July 2017 PREFACE 1. Scope This publication provides doctrine for conducting geospatial intelligence (GEOINT) across the range of military operations. It describes GEOINT organizations, roles, responsibilities, and operational processes that support the planning and execution of joint operations. 2. Purpose This publication has been prepared under the direction of the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (CJCS). It sets forth joint doctrine to govern the activities and performance of the Armed Forces of the United States in joint operations, and it provides considerations for military interaction with governmental and nongovernmental agencies, multinational forces, and other interorganizational partners. It provides military guidance for the exercise of authority by combatant commanders and other joint force commanders (JFCs) and prescribes joint doctrine for operations and training. It provides military guidance for use by the Armed Forces in preparing and executing their plans and orders. It is not the intent of this publication to restrict the authority of the JFC from organizing the force and executing the mission in a manner the JFC deems most appropriate to ensure unity of effort in the accomplishment of objectives. 3. Application a. Joint doctrine established in this publication applies to the Joint Staff, commanders of combatant commands, subordinate unified commands, joint task forces, subordinate components of these commands, the Services, and combat support agencies. -

Defense Logistics Agency (DLA)

UNCLASSIFIED Department of Defense Fiscal Year (FY) 2021 Budget Estimates February 2020 Defense Logistics Agency Defense-Wide Justification Book Volume 5 of 5 Research, Development, Test & Evaluation, Defense-Wide UNCLASSIFIED UNCLASSIFIED THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK UNCLASSIFIED UNCLASSIFIED Defense Logistics Agency • Budget Estimates FY 2021 • RDT&E Program Table of Volumes Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency............................................................................................................. Volume 1 Missile Defense Agency................................................................................................................................................... Volume 2 Office of the Secretary Of Defense................................................................................................................................. Volume 3 Chemical and Biological Defense Program....................................................................................................................Volume 4 Defense Contract Audit Agency...................................................................................................................................... Volume 5 Defense Contract Management Agency......................................................................................................................... Volume 5 Defense Counterintelligence and Security Agency.......................................................................................................Volume 5 Defense -

Gao-21-278, Defense Cybersecurity

United States Government Accountability Office Report to the Committee on Armed Services, House of Representatives June 2021 DEFENSE CYBERSECURITY Defense Logistics Agency Needs to Address Risk Management Deficiencies in Inventory Systems GAO-21-278 June 2021 DEFENSE CYBERSECURITY Defense Logistics Agency Needs to Address Risk Management Deficiencies in Inventory Systems Highlights of GAO-21-278, a report to the Committee on Armed Services, House of h Representatives Why GAO Did This Study What GAO Found In November 2018 DOD’s Survivable For six selected inventory management systems that support processes for Logistics Task Force examined current procuring, cataloging, distributing, and disposing of materiel, the Defense and emerging threats to DOD logistics, Logistics Agency (DLA) fully addressed two of the Department of Defense’s including cybersecurity threats. The task (DOD) six cybersecurity risk management steps and partially addressed the force concluded that DOD’s inventory other four. Specifically, the agency categorized the systems based on risk and management systems were potentially vulnerable to cyberattacks, and that DOD established an implementation approach for security controls. However, it only did not have corrective action plans to partially addressed the four risk management steps of selecting, assessing, mitigate the potential risks posed by authorizing, and monitoring security controls (see figure). associated vulnerabilities. Extent to Which the Defense Logistics Agency Addressed the Department of Defense’s Risk House Report 116-120, accompanying a Management Steps for Six Selected Inventory Management Systems bill for the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2020, included a provision for GAO to evaluate DOD’s efforts to manage cybersecurity risks to the DOD supply chain. -

Chapter Xii—Defense Logistics Agency

CHAPTER XII—DEFENSE LOGISTICS AGENCY SUBCHAPTER A [RESERVED] SUBCHAPTER B—MISCELLANEOUS Part Page 1280 Investigating and processing certain noncontrac- tual claims and reporting related litigation ........ 265 1285 Defense Logistics Agency Freedom of Information Act Program ......................................................... 268 1288 Registration of privately owned motor vehicles ..... 287 1290 Preparing and processing minor offenses and viola- tion notices referred to U.S. District Courts ....... 289 1292 Security of DLA activities and resources ............... 297 263 VerDate Nov<24>2008 13:21 Aug 25, 2009 Jkt 217129 PO 00000 Frm 00273 Fmt 8008 Sfmt 8008 Y:\SGML\217129.XXX 217129 erowe on DSK5CLS3C1PROD with CFR VerDate Nov<24>2008 13:21 Aug 25, 2009 Jkt 217129 PO 00000 Frm 00274 Fmt 8008 Sfmt 8008 Y:\SGML\217129.XXX 217129 erowe on DSK5CLS3C1PROD with CFR SUBCHAPTER A [RESERVED] SUBCHAPTER B—MISCELLANEOUS PART 1280—INVESTIGATING AND this part 1280, to investigate and proc- PROCESSING CERTAIN NON- ess claims within the purview of this CONTRACTUAL CLAIMS AND RE- part 1280. (b) Member of the Army, member of the PORTING RELATED LITIGATION Navy, member of the Marine Corps, mem- ber of the Air Force. Officers and en- Sec. 1280.1 Purpose and scope. listed personnel of these Military Serv- 1280.2 Definitions. ices. 1280.3 Significant changes. 1280.4 Responsibilities. § 1280.3 Significant changes. 1280.5 Procedures. This revision provides current cita- AUTHORITY: 5 U.S.C. 301; 10 U.S.C. 125; 28 tions to the Army regulations which U.S.C. 2672; and DoD Directive 5105.22 dated have superseded those previously pre- December 9, 1965. scribed for the processing of some SOURCE: 39 FR 19470, June 3, 1974, unless claims. -

Defense Logistics Agency (DLA)

UNCLASSIFIED Department of Defense Fiscal Year (FY) 2017 President's Budget Submission February 2016 Defense Logistics Agency Defense-Wide Justification Book Volume 5 of 5 Research, Development, Test & Evaluation, Defense-Wide UNCLASSIFIED UNCLASSIFIED THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK UNCLASSIFIED UNCLASSIFIED Defense Logistics Agency • President's Budget Submission FY 2017 • RDT&E Program Table of Volumes Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency............................................................................................................. Volume 1 Missile Defense Agency................................................................................................................................................... Volume 2 Office of the Secretary Of Defense................................................................................................................................. Volume 3 Chemical and Biological Defense Program....................................................................................................................Volume 4 Defense Contract Management Agency......................................................................................................................... Volume 5 DoD Human Resources Activity...................................................................................................................................... Volume 5 Defense Information Systems Agency............................................................................................................................Volume -

Role of the Defense Health Agency Medical Logistics Directorate

Defense Health Agency Medical Logistics Directorate Chapter 61 ROLE OF THE DEFENSE HEALTH AGENCY MEDICAL LOGISTICS DIRECTORATE Victor Acevedo, PA-C, MPAS, and Keary Johnston, PA-C, MPAS Introduction The Defense Health Agency Medical Logistics Directorate (DHA MEDLOG), formerly known as the Defense Medical Materiel Program Office, located at Fort Detrick, Maryland (Figure 61-1), is a joint activity under the direction, authority, and control of the Defense Health Agency (DHA). Since the DHA MEDLOG’s inception, its focus has been medical materiel standardization within the Department of Defense (DOD).1 The DHA has tasked the MEDLOG with integrating and delivering medical logistics materiel, equipment, and services along the continuum of operational and institutional Military Figure 61-1. The Defense Medical Logistics (MEDLOG) Center on Fort Detrick, Maryland, is home to the Defense Health Agency MEDLOG Directorate (2020). 1 US Army Physician Assistant Handbook Health System missions.1 The DHA MEDLOG is supported by an office staffed with diverse clinicians and non-clinicians, including an Army physician assistant (PA), registered nurses, pharmacists, laboratory officers, biomedical equipment technicians, medical logisticians, information management staff, and support personnel representing all the services. Job Duties and Responsibilities The DHA MEDLOG PA serves as chief of the Clinical Product Analysis Office (Figure 61-2). This office’s main role is to provide accurate and appropriate clinical input to the military medical logistics community. The chief is responsible for (a) providing input as a clinical subject matter expert to support current and new medical materiel and contingency readiness; (b) helping identify new requirements and processes within the DOD supply system to support joint and service Figure 6-2. -

DEFENSE LOGISTICS AGENCY WORKING CAPITAL FUND Chief Financial Officer Annual Financial Statement Fiscal Year 1998

AMERICA’S LOGISTICS COMBAT SUPPORT AGENCY DEFENSE LOGISTICS AGENCY WORKING CAPITAL FUND Chief Financial Officer Annual Financial Statement Fiscal Year 1998 March 1, 1999 MESSAGEFROMTHEDIRECTOR ince its establishment as the Defense Supply Agency in 1961, DLA has supported every war, every major contingency, and every theater of operations where our sailors, airmen, soldiers and marines have been deployed. We have been instrumental in ensuring victory by America’s Armed Forces by providing required supplies and services, around the clock, around the world. DLA has received two unit citations, which attest to our focus and ethos as America’s Logistics Combat Support Agency. We are now entering a new century that will provide the most significant period of change in our Armed Forces since World War II. As modern warfare increases in technological sophistication, speed, and complexity, logistics and acquisition organizations must change to keep pace. To remain relevant, DLA will reshape and refocus, applying the same innovation, teamwork, warfighter focus, selfless Director,DefenseLogisticsAgency service, and professionalism that has made us LieutenantGeneralHenryT.Glisson so successful during the past 37 years. UnitedStatesArmy Our refocus and reshaping included revisiting will continue to benefit immensely by our the DLA Strategic Plan during FY 1998. The initiatives – scarce resources can be diverted to Strategic Plan defines our vision, mission, much needed weapons systems values, goals and objectives, and establishes modernization. metrics to measure our progress. It emphasizes our support of the Department of I believe you will find that the DLA financial Defense’s Joint Vision 2010 and its emphasis statements for FY 1998 represent the results of on focused logistics. -

Defense Logistics Agency - Defense Information Systems Agency Charter Review

Submitted to the Deputy Secretary of Defense Defense Logistics Agency - Defense Information Systems Agency Charter Review DBB FY20-03 An examination of the designated roles and missions of the Defense Logistics Agency and Defense Information Systems Agency November 13, 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................................ 3 PREFACE ...................................................................................................................................................... 6 TASK ............................................................................................................................................................ 6 TASK GROUP ............................................................................................................................................... 7 APPROACH AND METHODOLOGY ............................................................................................................... 7 THE STRATEGIC IMPERATIVE ...................................................................................................................... 8 BACKGROUND ............................................................................................................................................. 9 CHARTER COMPARISONS .......................................................................................................................... 12 Defense Logistics Agency ................................................................................................................. -

DEFENSE AGENCIES Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency

DEFENSE AGENCIES Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency 3701 North Fairfax Drive, Arlington, VA 22203–1714 Phone, 703–526–6630. Internet, www.darpa.mil. Director ANTHONY J. TETHER Deputy Director JANE A. ALEXANDER The Defense Advanced Research development projects and conducts Projects Agency is a separately demonstration projects appropriate for organized agency within Department of joint programs, programs in support of Defense and is under the authority, deployed forces, or selected programs of direction, and control of the Under the military departments. To this end, the Secretary of Defense (Acquisition, Agency arranges, manages, and directs Technology & Logistics). The Agency serves as the central research and the performance of work connected with development organization of the assigned advanced projects by the Department of Defense with a primary military departments, other Government responsibility to maintain U.S. agencies, individuals, private business technological superiority over potential entities, and educational or research adversaries. It pursues research and institutions, as appropriate. For further information, contact the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, 3701 North Fairfax Drive, Arlington, VA 22203–1714. Phone, 703–526–6630. Internet, www.darpa.mil. Defense Commissary Agency 1300 ‘‘E’’ Avenue, Fort Lee, VA 23801–1800 Phone, 804–734–8253. Internet, www.commissaries.com. Director MAJ. GEN. ROBERT J. COURTER, JR., USAF Deputy Director PATRICK NIXON Chief, Support Staff LAURA R. HARRELL The Defense Commissary Agency was operational supervision of the established in 1990 and is under the Commissary Operating Board. The authority, direction, and control of the Agency is responsible for providing an Under Secretary of Defense for efficient and effective worldwide system Personnel and Readiness and the of commissaries for selling groceries and 193 VerDate 11-MAY-2000 02:17 Aug 24, 2002 Jkt 010199 PO 00000 Frm 00193 Fmt 6995 Sfmt 6995 W:\DISC\189864TX.XXX txed01 PsN: txed01 194 U.S. -

Defense Primer: the Defense Logistics Agency

December 15, 2020 Defense Primer: The Defense Logistics Agency Established under Title 10, Sections 191 and 192, of the distribute about 5 million distinct consumable, expendable United States Code (U.S.C.), the Defense Logistics Agency and reparable items” to its military customers. The agency (DLA) is a single Department of Defense (DOD) agency contracts for high-volume, commercially available items responsible for supply or service activities common to all based on customer requirements. It then distributes these military departments. Section 193 of Title 10 identifies items directly to the requesting customer (e.g., a shipyard or DLA as a combat support agency, a designation that maintenance depot), or stores them for later delivery. DLA according to DLA, “gives DLA a formal oversight also allows customers to order supplies directly from relationship with the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff integrated supply chain contractors if they are an approved and allows combatant commanders to request specific provider through the Prime Vendor Program (Figure 2). support from the agency.” Under these authorities, the agency manages the global supply chain for DOD and its Figure 2. DLA Supply Chain Management Process partners by providing procurement, storage, distribution, disposition, and other technical services to its customers. DLA is one of several organizations that are essential to the Joint Logistics Enterprise (see Joint Publication 4-0). DLA is headquartered in Fort Belvoir, VA. The agency operates in most U.S. states and territories and in 28 foreign countries (Figure 1). Annually, it provides more than $42 billion worth of goods and services to DOD, other federal agencies, and partner and allied nations. -

Real ID Act, Compliance, Limited Extension

Vol. 75, No. 23 Tinker Air Force Base, Okla. Friday, June 9, 2017 72nd ABW has moved to Bldgs. 1002 Inhofe tours Tinker and 7005 Page 4 INSIDE 552nd ACW cuts ribbon on new medical clinic Lt. Gen. Lee K. Levy II Page 5 AFSC/CC Message Honoring an enduring Air Force photo by Darren D. Heusel symbol Lt. Gen. Lee K. Levy II, Air Force Sustainment Center commander, right, looks on as Sen. Jim Inhofe Massive boards his airplane positioned in front of Base Ops following a brief visit to Tinker Air Force Base May Lt. Gen. Lee K. Levy II undertaking 31. The senator was in the local area to attend a number of community events and received a quick Air Force Sustainment Center of the KC-135 tour of the base to discuss ongoing initiatives he’s working on Capitol Hill. The Oklahoma senator and Commander double-belly pilot occasionally flies his own plane, a Grumman Tiger, when conducting business at Tinker. removal AFSC Airmen, Every year June 14 is a Page 6-7 special, nationally recognized Real ID Act, compliance, day to honor our flag, which Tinker’s Healthy remains an enduring symbol of Lifestyle Festival hope, liberty, and freedom. limited extension On June 14, 1777, the Page 8 72nd Air Base Wing Public Affairs U.S. Permanent resident card (Form I-551) Continental Congress adopted • U.S. certificate of naturalization or certificate a resolution establishing the Tinker Events The state of Oklahoma has been on a limited of citizenship (Form N-550) United States flag as having Calendar extension for the REAL ID Act from the Department • Employment authorization document issued by 13 stripes alternating between of Homeland Security through June 6. -

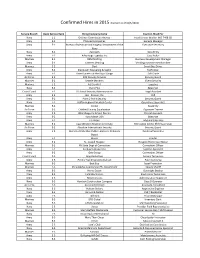

Confirmed Hires in 2015 (Current As of 10/5/2015)

Confirmed Hires in 2015 (Current as of 10/5/2015) Service Branch (Last) Service Rank Hiring Company Name Position Hired For Navy E-1 Defense Commissary Agency Food Service Worker WG-7408-02 Army E-1 Planned Companies General Manager Army E-1 Bureau of Medicine and Surgery, Department of the Executive Secretary Navy Navy E-1 Aerotech Data Entry Army E-1 Advantage Logistics Inc Case Picker Marines E-1 BBM Staffing Business Development Manager Army E-1 Canteen Vending Vending machine merchandiser Marines E-2 Dart Smart Bus Driver Army E-2 Kienbuam Excavating & Septic Technician Army E-2 River Runners at the Royal Gorge Raft Guide Air Force E-2 SOS Security Services Security Guard Marines E-2 Seattle Mariners Event Security Marines E-2 A1 Dry Wall Logistics Navy E-2 Guns Plus Salesman Coast Guard E-2 US Social Security Administration Legal Assistant Army E-2 JGA - Beacon, Inc. DLP Army E-2 Point 2 Point Security Security Guard Navy E-2 Halifax Regional Medical Center Operations Specialist Marines E-2 Crown Assembly Air Force E-2 Oakland County Equalization Appraiser Trainee Army E-2 Winnebago Co School District Clerical Assistant Army E-2 Auto Match USA Salesman Army E-2 TruGreen Inbound Sales Rep Marines E-2 Case Western Reserve University Recreation Center Shift Supervisor Air Force E-2 Absolute International Security Security Guard Army E-2 District of Columbia Public Employee Relations Paralegal Specialist Board Army E-2 Macco Painter Army E-2 St. Joseph Hospice Hospice/Home Care Nurse Marines E-2 NY State Dept of Corrections Corrections