Panel Discussion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Relevant Market/ Region Commercial Transaction Rates

Last Updated: 31, May 2021 You can find details about changes to our rates and fees and when they will apply on our Policy Updates Page. You can also view these changes by clicking ‘Legal’ at the bottom of any web-page and then selecting ‘Policy Updates’. Domestic: A transaction occurring when both the sender and receiver are registered with or identified by PayPal as residents of the same market. International: A transaction occurring when the sender and receiver are registered with or identified by PayPal as residents of different markets. Certain markets are grouped together when calculating international transaction rates. For a listing of our groupings, please access our Market/Region Grouping Table. Market Code Table: We may refer to two-letter market codes throughout our fee pages. For a complete listing of PayPal market codes, please access our Market Code Table. Relevant Market/ Region Rates published below apply to PayPal accounts of residents of the following market/region: Market/Region list Taiwan (TW) Commercial Transaction Rates When you buy or sell goods or services, make any other commercial type of transaction, send or receive a charity donation or receive a payment when you “request money” using PayPal, we call that a “commercial transaction”. Receiving international transactions Where sender’s market/region is Rate Outside of Taiwan (TW) Commercial Transactions 4.40% + fixed fee Fixed fee for commercial transactions (based on currency received) Currency Fee Australian dollar 0.30 AUD Brazilian real 0.60 BRL Canadian -

Relevant Market/ Region Commercial Transaction Rates

Last Updated: 31, May 2021 You can find details about changes to our rates and fees and when they will apply on our Policy Updates Page. You can also view these changes by clicking ‘Legal’ at the bottom of any web-page and then selecting ‘Policy Updates’. Domestic: A transaction occurring when both the sender and receiver are registered with or identified by PayPal as residents of the same market. International: A transaction occurring when the sender and receiver are registered with or identified by PayPal as residents of different markets. Certain markets are grouped together when calculating international transaction rates. For a listing of our groupings, please access our Market/Region Grouping Table. Market Code Table: We may refer to two-letter market codes throughout our fee pages. For a complete listing of PayPal market codes, please access our Market Code Table. Relevant Market/ Region Rates published below apply to PayPal accounts of residents of the following market/region: Market/Region list Vietnam (VN) Commercial Transaction Rates When you buy or sell goods or services, make any other commercial type of transaction, send or receive a charity donation or receive a payment when you “request money” using PayPal, we call that a “commercial transaction”. Receiving international transactions Where sender’s market/region is Rate Outside of Vietnam (VN) Commercial Transactions 4.40% + fixed fee Fixed fee for commercial transactions (based on currency received) Currency Fee Australian dollar 0.30 AUD Brazilian real 0.60 BRL Canadian dollar -

Sada Reddy: Fiji's Economic Situation

Sada Reddy: Fiji’s economic situation Talk by Mr Sada Reddy, Governor of the Reserve Bank of Fiji, to the Ministry of Information, Communications and Archives, Suva, 22 April 2009. * * * I’m very humbled that I had been appointed the Governor of the RBF. I have taken this responsibility at a time when the whole world is going through very difficult times. And, of course, as you know we have our own economic problems here. There are a lot of challenges ahead of us but I am very confident that with my appointment I’ll be able to make a big difference in the recovery of the Fiji economy. I realize the big challenges lying ahead. But given my long experience in this organization running RB is not going to be difficult for me. I’ve worked in the RBF for last 34 yrs in all the important policy areas and have been the Deputy Governor for the last 14 years so. It’s the policy choices that I have to make would be the challenge. I need the cooperation of the Government, of the financial system, in particular, the banks, and the business community to make our policies successful. In the next few months I’ll be actively engaging all the key players and explain our policies and what we need to do so that we are able to somehow buffer ourselves from what’s happening around the world. I think we underestimated the impact of the global crisis on the Fiji economy. It is having a very major impact. -

Country Scheme Alpha 3 Alpha 2 Currency Albania MC / VI ALB AL

Country Scheme Alpha 3 Alpha 2 Currency Albania MC / VI ALB AL Lek Algeria MC / VI DZA DZ Algerian dinar Argentina MC / VI ARG AR Argentine peso Australia MC / VI AUS AU Australian dollar -Christmas Is. -Cocos (Keeling) Is. -Heard and McDonald Is. -Kiribati -Nauru -Norfolk Is. -Tuvalu Christmas Island MC CXR CX Australian dollar Cocos (Keeling) Islands MC CCK CC Australian dollar Heard and McDonald Islands MC HMD HM Australian dollar Kiribati MC KIR KI Australian dollar Nauru MC NRU NR Australian dollar Norfolk Island MC NFK NF Australian dollar Tuvalu MC TUV TV Australian dollar Bahamas MC / VI BHS BS Bahamian dollar Bahrain MC / VI BHR BH Bahraini dinar Bangladesh MC / VI BGD BD Taka Armenia VI ARM AM Armenian Dram Barbados MC / VI BRB BB Barbados dollar Bermuda MC / VI BMU BM Bermudian dollar Bolivia, MC / VI BOL BO Boliviano Plurinational State of Botswana MC / VI BWA BW Pula Belize MC / VI BLZ BZ Belize dollar Solomon Islands MC / VI SLB SB Solomon Islands dollar Brunei Darussalam MC / VI BRN BN Brunei dollar Myanmar MC / VI MMR MM Myanmar kyat (effective 1 November 2012) Burundi MC / VI BDI BI Burundi franc Cambodia MC / VI KHM KH Riel Canada MC / VI CAN CA Canadian dollar Cape Verde MC / VI CPV CV Cape Verde escudo Cayman Islands MC / VI CYM KY Cayman Islands dollar Sri Lanka MC / VI LKA LK Sri Lanka rupee Chile MC / VI CHL CL Chilean peso China VI CHN CN Colombia MC / VI COL CO Colombian peso Comoros MC / VI COM KM Comoro franc Costa Rica MC / VI CRI CR Costa Rican colony Croatia MC / VI HRV HR Kuna Cuba VI Czech Republic MC / VI CZE CZ Koruna Denmark MC / VI DNK DK Danish krone Faeroe Is. -

Currency Exchange Rates

Pacific Data Hub .Stat metadata Currency exchange rates Data description Title Currency exchange rates Description Number of U.S. Dollars per of domestic currency unit for currencies used in Pacific Island Countries and Territories. Monthly and yearly values for end-of-period and period-average exchange rates since 1950 are based on data from IMF International Financial Statistics. Data identification Identifier SPC:DF_CURRENCIES(2.0) URL https://stats.pacificdata.org/vis?locale=en&facet=6nQpoAP&constraints[0]=6nQpoAP%2C0%7CEconomy%23ECO%23&start=0 &dataflow[datasourceId]=SPC2&dataflow[dataflowId]=DF_CURRENCIES&dataflow[agencyId]=SPC&dataflow[version]=2.0 Data source Monthly and yearly currency exchange rates are collected from IMF International Financial Statistics, using the SDMX API. Exchange rates are domestic currency per U.S. Dollar for currencies used by Pacific Island Countries and Territories : Australian Dollar, CFP Franc, Fiji Dollar, Kina, New Zealand Dollar, Pa’anga, Solomon Islands Dollar, Tala and Vatu. End of period rates and period average rates are collected. The call to IMF API used to collect the data is : http://dataservices.imf.org/REST/SDMX_XML.svc/CompactData/IFS/A+M.FJ+NC+PG+SB+TO+VU+WS+AU+NZ.ENDA_XDC_USD_RATE+ENDE_XD C_USD_RATE?startPeriod=1950&endPeriod=2050 Data processing Data values are rounded to 4 decimal places. Quarterly values are calculated from monthly values: end of perdiod value of the last month of the quarter is used for end of period rate, average of average monthly rates is used for period average rate. Reference area ISO3166-1 alpha 2 codes are recoded to ISO 4217 currency codes this way : Temporal coverage First period 1950 Last period Current month-1 Data scheduling Frequency Monthly and yearly Timeliness Data is refreshed at the beginning of each month, timeliness of data for individual currencies has not been assessed. -

Rethinking Forward and Spot Exchange Rates in Internationsal Trading

RETHINKING FORWARD AND SPOT EXCHANGE RATES IN INTERNATIONSAL TRADING Guan Jun Wang, Savannah State University ABSTRACT This study uses alternative testing methods to re-examines the relation between the forward exchange rate and corresponding future spot rate from both perspectives of the same currency pair traders using both direct and indirect quotations in empirical study as opposed to the conventional logarithm regression method, from one side of traders’ (often dollar sellers) perspective, using one way currency pair quotation (often direct quotation). Most of the empirical testing results in this paper indicate that the forward exchange rates are downward biased from the dollar sellers’ perspective, and upward biased from the dollar buyers’ perspective. The paper further contends that non-risk neutrality assumption may potentially explain the existence of the bias. JEL Classifications: F31, F37, C12 INTRODUCTION Any international transaction involving foreign currency exchange is risky due to economic, technical and political factors which can result in volatile exchange rates thus hamper international trading. The forward exchange contract is an effective hedging tool to lower such risk because it can lock an exchange rate for a specific amount of currency for a future date transaction and thus enables traders to calculate the exact quantity and payment of the import and export prior to the transaction date without considering the future exchange rate fluctuation. However hedging in the forward exchange market is not without cost, and the real costs are the differential between the forward rate and the future spot rate if the future spot rate turns out to be favorable to one party, and otherwise, gain will result. -

Understanding Currency Hedging

Understanding currency hedging At Kiwi Wealth, we use currency hedging to reduce the risk to returns that can arise from the change in value of one currency against another. Being exposed to volatile movements in foreign currencies adds another element of risk to our portfolios and to manage the risk we use a technique called currency hedging. What is currency hedging? The best way to understand hedging is to think of it as reducing or removing a particular risk. In the case of currency hedging, the risk is that if a currency changes in value it can adversely affect the returns on a portfolio. There are different instruments that a Manager can use to help manage this risk. One such instrument is a forward currency contract, in which the managers locks in the future value of a currency to the current rate of exchange. Currency hedging has also given an additional return thanks to New Zealand’s interest rates, which are higher than most offshore rates. Kiwi Wealth portfolios are invested globally, which means their returns in New Zealand dollars are exposed to movements in the exchange rate. In other words, the returns on overseas investments are muted by a rising Kiwi dollar. Alternatively – and more positively - the gains on overseas investments can be strengthened by a falling New Zealand dollar. To partially protect against a rising New Zealand dollar, we hedge a proportion of portfolios to reduce exposure to the currency risk. How does currency hedging work at Kiwi Wealth? Kiwi Wealth fully hedges our NZ Fixed Interest strategy (including the Kiwi Wealth Fixed Interest PIE) so this portfolio is immune from movements in foreign currencies. -

International Currency Codes

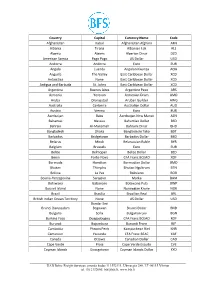

Country Capital Currency Name Code Afghanistan Kabul Afghanistan Afghani AFN Albania Tirana Albanian Lek ALL Algeria Algiers Algerian Dinar DZD American Samoa Pago Pago US Dollar USD Andorra Andorra Euro EUR Angola Luanda Angolan Kwanza AOA Anguilla The Valley East Caribbean Dollar XCD Antarctica None East Caribbean Dollar XCD Antigua and Barbuda St. Johns East Caribbean Dollar XCD Argentina Buenos Aires Argentine Peso ARS Armenia Yerevan Armenian Dram AMD Aruba Oranjestad Aruban Guilder AWG Australia Canberra Australian Dollar AUD Austria Vienna Euro EUR Azerbaijan Baku Azerbaijan New Manat AZN Bahamas Nassau Bahamian Dollar BSD Bahrain Al-Manamah Bahraini Dinar BHD Bangladesh Dhaka Bangladeshi Taka BDT Barbados Bridgetown Barbados Dollar BBD Belarus Minsk Belarussian Ruble BYR Belgium Brussels Euro EUR Belize Belmopan Belize Dollar BZD Benin Porto-Novo CFA Franc BCEAO XOF Bermuda Hamilton Bermudian Dollar BMD Bhutan Thimphu Bhutan Ngultrum BTN Bolivia La Paz Boliviano BOB Bosnia-Herzegovina Sarajevo Marka BAM Botswana Gaborone Botswana Pula BWP Bouvet Island None Norwegian Krone NOK Brazil Brasilia Brazilian Real BRL British Indian Ocean Territory None US Dollar USD Bandar Seri Brunei Darussalam Begawan Brunei Dollar BND Bulgaria Sofia Bulgarian Lev BGN Burkina Faso Ouagadougou CFA Franc BCEAO XOF Burundi Bujumbura Burundi Franc BIF Cambodia Phnom Penh Kampuchean Riel KHR Cameroon Yaounde CFA Franc BEAC XAF Canada Ottawa Canadian Dollar CAD Cape Verde Praia Cape Verde Escudo CVE Cayman Islands Georgetown Cayman Islands Dollar KYD _____________________________________________________________________________________________ -

New Zealand Dollar Report

New Zealand Dollar Report Report by PwC Treasury Advisory 9 February 2021 Table of contents NZD/USD forecast and generic hedging recommendations 3 NZD/USD remains within range as data continues to print strongly 4 Key drivers of the NZD/USD exchange rate outlook 6 Get in touch 7 pwc.co.nz/services/treasury-and-debt-advisory 9 February 2021 PwC 2 NZD/USD forecast and generic hedging recommendations Spot rate: 0.7165 Exporter hedging recommendations: ● 0 - 12 month = Use existing hedging. Ensure midpoints are maintained with orders between 0.7100 and 0.7010, with staggered orders to 0.6930 in order to be near maximums. Clients contact us for specific recommendations. ● ● 12 - 24 month (non-filter test activated) = Target moves back below 0.7000 in order to layer in new hedging. Preference for collar options for any new hedging at this time. Clients contact us for specific recommendations. ● ● 12+ months (filter test activated) = 2-year filter test activation requires spot rate of 0.6016. 3-year filter test activation requires spot rate of 0.6005. Core NZD/USD exchange rate views Importer hedging recommendations: ● Global support factors for the NZD (through equity markets, EUR/USD, AUD/USD) ● 0 - 6 month payments = Maintain maximums of policy above 0.7150. continuing to provide upward pressure on the exchange rate (EUR through gradual ● fiscal integration, AUD via strong commodities and RBA settings, equities through ● 6 - 12 month payments = Should be well hedged. Replenishing recently post-vaccine upward swing and rotation). Equity market pricing extremely optimistic, so struck orders between 0.7200 and 0.7300 to be halfway between slower acceleration expected in 2021, tempering the extent of NZD strength. -

Official Journal C 1 of the European Union

Official Journal C 1 of the European Union Volume 58 English edition Information and Notices 6 January 2015 Contents IV Notices NOTICES FROM EUROPEAN UNION INSTITUTIONS, BODIES, OFFICES AND AGENCIES European Commission 2015/C 1/01 Euro exchange rates .............................................................................................................. 1 2015/C 1/02 Euro exchange rates .............................................................................................................. 2 2015/C 1/03 Euro exchange rates .............................................................................................................. 3 EN 6.1.2015 EN Official Journal of the European Union C 1/1 IV (Notices) NOTICES FROM EUROPEAN UNION INSTITUTIONS, BODIES, OFFICES AND AGENCIES EUROPEAN COMMISSION Euro exchange rates (1) 31 December 2014 (2015/C 1/01) 1 euro = Currency Exchange rate Currency Exchange rate USD US dollar 1,2141 CAD Canadian dollar 1,4063 JPY Japanese yen 145,23 HKD Hong Kong dollar 9,417 DKK Danish krone 7,4453 NZD New Zealand dollar 1,5525 GBP Pound sterling 0,7789 SGD Singapore dollar 1,6058 SEK Swedish krona 9,393 KRW South Korean won 1 324,8 CHF Swiss franc 1,2024 ZAR South African rand 14,0353 ISK Iceland króna CNY Chinese yuan renminbi 7,5358 NOK Norwegian krone 9,042 HRK Croatian kuna 7,658 BGN Bulgarian lev 1,9558 IDR Indonesian rupiah 15 076,1 CZK Czech koruna 27,735 MYR Malaysian ringgit 4,2473 HUF Hungarian forint 315,54 PHP Philippine peso 54,436 LTL Lithuanian litas 3,45280 RUB Russian rouble 72,337 PLN Polish zloty 4,2732 THB Thai baht 39,91 RON Romanian leu 4,4828 BRL Brazilian real 3,2207 TRY Turkish lira 2,832 MXN Mexican peso 17,8679 AUD Australian dollar 1,4829 INR Indian rupee 76,719 (1) Source: reference exchange rate published by the ECB. -

FAO Country Name ISO Currency Code* Currency Name*

FAO Country Name ISO Currency Code* Currency Name* Afghanistan AFA Afghani Albania ALL Lek Algeria DZD Algerian Dinar Amer Samoa USD US Dollar Andorra ADP Andorran Peseta Angola AON New Kwanza Anguilla XCD East Caribbean Dollar Antigua Barb XCD East Caribbean Dollar Argentina ARS Argentine Peso Armenia AMD Armeniam Dram Aruba AWG Aruban Guilder Australia AUD Australian Dollar Austria ATS Schilling Azerbaijan AZM Azerbaijanian Manat Bahamas BSD Bahamian Dollar Bahrain BHD Bahraini Dinar Bangladesh BDT Taka Barbados BBD Barbados Dollar Belarus BYB Belarussian Ruble Belgium BEF Belgian Franc Belize BZD Belize Dollar Benin XOF CFA Franc Bermuda BMD Bermudian Dollar Bhutan BTN Ngultrum Bolivia BOB Boliviano Botswana BWP Pula Br Ind Oc Tr USD US Dollar Br Virgin Is USD US Dollar Brazil BRL Brazilian Real Brunei Darsm BND Brunei Dollar Bulgaria BGN New Lev Burkina Faso XOF CFA Franc Burundi BIF Burundi Franc Côte dIvoire XOF CFA Franc Cambodia KHR Riel Cameroon XAF CFA Franc Canada CAD Canadian Dollar Cape Verde CVE Cape Verde Escudo Cayman Is KYD Cayman Islands Dollar Cent Afr Rep XAF CFA Franc Chad XAF CFA Franc Channel Is GBP Pound Sterling Chile CLP Chilean Peso China CNY Yuan Renminbi China, Macao MOP Pataca China,H.Kong HKD Hong Kong Dollar China,Taiwan TWD New Taiwan Dollar Christmas Is AUD Australian Dollar Cocos Is AUD Australian Dollar Colombia COP Colombian Peso Comoros KMF Comoro Franc FAO Country Name ISO Currency Code* Currency Name* Congo Dem R CDF Franc Congolais Congo Rep XAF CFA Franc Cook Is NZD New Zealand Dollar Costa Rica -

Assessing the Maturity of the AUD/NZD Market

Assessing the maturity of the AUD/NZD market Russell Poskitt +++ University of Auckland Alastair Marsden University of Auckland Abstract We use a high frequency data set to examine information flows between the direct and indirect markets for the AUD/NZD. Our results show that information flows are dominated by the contemporaneous information flow during the most active part of the trading day and by the lagged flow of information from the indirect market when trading activity is low. The lagged flow of information from the direct market to the indirect market is never the dominant channel. These results show that the US dollar markets for the Australasian currency pair remain the locus of price discovery and suggest that the direct AUD/NZD market is still relatively immature, despite the recent growth in trading activity. JEL classification : G13, G14 Keywords : foreign exchange markets; price discovery + Department of Accounting and Finance, University of Auckland , Private Bag 92019, Auckland, New Zealand , Tel: 64 9 373 7599 Fax: 64 9 373 7406, Email: [email protected] Assessing the maturity of the AUD/NZD market Abstract We use a high frequency data set to examine information flows between the direct and indirect markets for the AUD/NZD. Our results show that information flows are dominated by the contemporaneous information flow during the most active part of the trading day and by the lagged flow of information from the indirect market when trading activity is low. The lagged flow of information from the direct market to the indirect market is never the dominant channel.