THE INFLUENCE of EARLY JAPANESE EXPORT PORCELAIN on DUTCH DELFTWARE, 1660-1680 by Drs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fast Fossils Carbon-Film Transfer on Saggar-Fired Porcelain by Dick Lehman

March 2000 1 2 CERAMICS MONTHLY March 2000 Volume 48 Number 3 “Leaves in Love,” 10 inches in height, handbuilt stoneware with abraded glaze, by Michael Sherrill, Hendersonville, North FEATURES Carolina. 34 Fast Fossils 40 Carbon-Film Transfer on Saggar-Fired Porcelain by Dick Lehman 38 Steven Montgomery The wood-firing kiln at Buck Industrial imagery with rich texture and surface detail Pottery, Gruene, Texas. 40 Michael Sherrill 62 Highly refined organic forms in porcelain 42 Rasa and Juozas Saldaitis by Charles Shilas Lithuanian couple emigrate for arts opportunities 45 The Poetry of Punchong Slip-Decorated Ware by Byoung-Ho Yoo, Soo-Jong Ree and Sung-Jae Choi by Meghen Jones 49 No More Gersdey Borateby JejfZamek Why, how and what to do about it 51 Energy and Care Pit Firing Burnished Pots on the Beach by Carol Molly Prier 55 NitsaYaffe Israeli artist explores minimalist abstraction in vessel forms “Teapot,” approximately 9 inches in height, white 56 A Female Perspectiveby Alan Naslund earthenware with under Female form portrayed by Amy Kephart glazes and glazes, by Juozas and Rasa Saldaitis, 58 Endurance of Spirit St. Petersburg, Florida. The Work of Joanne Hayakawa by Mark Messenger 62 Buck Pottery 42 17 Years of Turnin’ and Burnin’ by David Hendley 67 Redware: Tradition and Beyond Contemporary and historical work at the Clay Studio “Bottle,” 7 inches in height, wheel-thrown porcelain, saggar 68 California Contemporary Clay fired with ferns and sumac, by The cover:“Echolalia,” San Francisco invitational exhibition Dick Lehman, Goshen, Indiana. 29½ inches in height, press molded and assembled, 115 Conquering Higher Ground 34 by Steven Montgomery, NCECA 2000 Conference Preview New York City; see page 38. -

Ming Dynasty Porcelain Plate Laura G

Wonders of Nature and Artifice Art and Art History Fall 2017 Blue-and-White Wonder: Ming Dynasty Porcelain Plate Laura G. Waters '19, Gettysburg College Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/wonders_exhibit Part of the Ancient, Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque Art and Architecture Commons, Fine Arts Commons, History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons, Industrial and Product Design Commons, and the Intellectual History Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Waters, Laura G., "Blue-and-White Wonder: Ming Dynasty Porcelain Plate" (2017). Wonders of Nature and Artifice. 12. https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/wonders_exhibit/12 This is the author's version of the work. This publication appears in Gettysburg College's institutional repository by permission of the copyright owner for personal use, not for redistribution. Cupola permanent link: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/wonders_exhibit/12 This open access student research paper is brought to you by The uC pola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The uC pola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Blue-and-White Wonder: Ming Dynasty Porcelain Plate Abstract This authentic Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) plate is a prime example of early export porcelain, a luminous substance that enthralled European collectors. The eg nerous gift of oJ yce P. Bishop in honor of her daughter, Kimberly Bishop Connors, Ming Dynasty Blue-and-White Plate is on loan from the Reeves Collection at Washington and Lee University in Lexington, Virginia. The lp ate itself is approximately 7.75 inches (20 cm) in diameter, and appears much deeper from the bottom than it does from the top. -

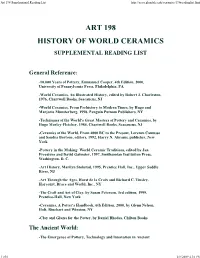

Art 198 Supplemental Reading List

Art 198 Supplemental Reading List http://seco.glendale.edu/ceramics/198readinglist.html ART 198 HISTORY OF WORLD CERAMICS SUPPLEMENTAL READING LIST General Reference: -10,000 Years of Pottery, Emmanuel Cooper, 4th Edition, 2000, University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia, PA -World Ceramics, An Illustrated History, edited by Robert J. Charleston, 1976, Chartwell Books, Seacaucus, NJ -World Ceramics, From Prehistory to Modern Times, by Hugo and Marjorie Munsterberg, 1998, Penguin Putnam Publishers, NY -Techniques of the World's Great Masters of Pottery and Ceramics, by Hugo Morley-Fletcher, 1984, Chartwell Books, Seacaucus, NJ -Ceramics of the World, From 4000 BC to the Present, Lorenzo Camusso and Sandra Bortone, editors, 1992, Harry N. Abrams, publisher, New York -Pottery in the Making: World Ceramic Traditions, edited by Jan Freestone and David Gaimster, 1997, Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, D. C. -Art History, Marilyn Stokstad, 1995, Prentice Hall, Inc., Upper Saddle River, NJ -Art Through the Ages, Horst de la Croix and Richard C. Tinsley, Harcourt, Brace and World, Inc., NY -The Craft and Art of Clay, by Susan Peterson, 3rd edition, 1999, Prentice-Hall, New York -Ceramics, A Potter's Handbook, 6th Edition, 2000, by Glenn Nelson, Holt, Rinehart and Winston, NY -Clay and Glazes for the Potter, by Daniel Rhodes, Chilton Books The Ancient World: -The Emergence of Pottery, Technology and Innovation in Ancient 1 of 6 2/8/2009 4:10 PM Art 198 Supplemental Reading List http://seco.glendale.edu/ceramics/198readinglist.html Societies, by William K.Barnett and John W. Hoopes, 1995, Simthsonian Institution Press, 1995, Washington, DC -Cycladic Art: The N. -

2013 EFP Catalog 19 April

Ephraim Pottery Studio Collection April 2013 Welcome! Dear pottery and tile enthusiasts, As you can see from this catalog, we’ve been busy working on new pottery and tiles over the past several months. While this is an ongo- ing process, we have also been taking a closer look at what we want our pottery to represent. Refocusing on our mission, we have been reminded how important the collaborative work environment is to our studio. When our artists bring their passion for their work to the group and are open to elevating their vision, boundaries seem to drop away. I like to think that our world would be a much better place if a collaborative approach could be emphasized in our homes, schools, and workplaces... in all areas of our lives, in fact. “We are better to- gether” is a motto that is in evidence every day at EFP. Many times in the creative process, we can develop a new concept most of the way quickly. Often, it’s that last 10% that requires work, grit and determination. It can take weeks, months, or even years to bring a new concept to fruition. Such has been the case with frames and stands for our tiles. Until recently, John Raymond was in charge of glaz- ing. As some of you know, John is also a talented woodworker who has been developing a line of quarter-sawn oak frames and stands for our tiles. While we have been able to display some of these at shows and in our galleries over the past year, we would like to make frames and stands available to all our customers. -

Leeds Arts Calendar LEEDS ARTS CALENDAR MICROFILMED Starting with the First Issue Published in 1947, the Entire Leeds Art Calendar Is Now Available on Micro- Film

Leeds Arts Calendar LEEDS ARTS CALENDAR MICROFILMED Starting with the first issue published in 1947, the entire Leeds Art Calendar is now available on micro- film. Write for information or send orders direct to: University Microfilms, Inc., 300N Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106, U.S.A. Leeds Art Collections Fund This is an appeal to all who are interested in the Arts. The Leeds Art Collections Fund is the source of regular funds for buying works of art for the Leeds collection. We want more subscribing members to give one and a half guineas or upwards each year. Why not identify yourself with the Art Gallery and Temple Newsam; receive your Arts Calendar free, receive invitations to all functions, private views and organised visits to places ot Cover Design interest, by writing for an application form to the Detail of a Staffordshire salt-glaze stoneware mug Hon Treasurer, E. M. Arnold Butterley Street, Leeds 10 with "Scratch Blue" decoration of a cattle auction Esq., scene; inscribed "John Cope 1749 Hear goes". From the Hollings Collection, Leeds. LEEDS ARTS CALENDAR No. 67 1970 THE AMENITIES COMMITTEE The Lord Mayor Alderman J. T. V. Watson, t.t..s (Chairman) Alderman T. W. Kirkby Contents Alderman A. S. Pedley, D.p.c. Alderman S. Symmonds Councillor P. N. H. Clokie Councillor R. I. Ellis, A.R.A.M. Councillor H. Farrell Editorial 2 J. Councillor Mrs. E. Haughton Councillor Mrs. Collector's Notebook D. E. Jenkins A Leeds 4 Councillor Mrs. A. Malcolm Councillor Miss C. A. Mathers Some Trifles from Leeds 12 Councillor D. -

CERAMICS MONTHLY a Letter from the Editor

lili.~o;.; ...... "~,~ I~,~.'il;:---.-::::~ ! 1 ~li~'. " " " -"-- :" ' " " ~ ''~: P #~" ...................... ~.c .~ ~7',.~,c-" =---.......... ,.,_,. ~-,~ !,' .......... i."' "~"" ~' ...... !I "'" ~ r~P.tfi.~. ......"-~ .............~:- - -~-~:==-.- .,,,~4~i t,_,i..... ,; ................... ~,~ ,~.i~'~ ..... -. ~,'...;;,. :,,,~.... ..... , , . ,¶~ ~'~ .... ...... i.,>-- ,,~ ........... ., ~ ~...... ~. ~' i .,.... .i .. - i .,.it ....... ~-i ;~ "~" o.., I llili'i~'lii llilillli'l " "" ............... i ill '~l It qL[~ ,, ,q ...... ..... .i~! 'l • IN ~, L'.,.-~':';" ............. ........ 'i'.~'~ ......... ~':',q. ~....~ • ~.,i ................... dl ..... i~,%,...;,, ......................... Ill ltj'llll 1". ........ : ...... " - "- ~1 ~,~.,.--..• ~:I,'.s ...... .................... I' '#~'~ .......................... ~; ~"" .. • .,:,.. _., I;.~P~,,,,...-...,,,.,l.,. ........,..._ .~ -.. ,,~l."'~ ........ ,~ ~,~'~'i '.. .................. ....... -,- l'..~ .......... .,.,.,,........... r4" ...." ' ~'~'"" -'- ~i i~,~'- ~>'- i ill. ....................... ,'., i,'; "" " ........ " • . it, 1 ~,:. i ~1' ~ ~'$~'~-,~,s',il~.;;;:.;' - " ~!'~~!" "4"' '~ "~'" "" I I~i', ~l~ I,J ..v ~,J ,.,, ,., i o. ~.. pj~ ~. ....... yit .~,,. .......... :,~ ,,~ t; .... ~ | I ~li~,. ,~ i'..~.. ~.. .... I TL-8, Ins Economical Chamber TOP-LOADING $14715 high f.o. bus, cra ELECTRIKILNS py .... ter Save your time . cut power costs! These ElectriKilns are de- signed for the special needs of hobbyist and teacher. Fast-firing up to 2300 ° F .... heat-saving . low -

1 the Willow Pattern

The East India Company at Home, 1757-1857 – UCL History The Willow Pattern: Dunham Massey By Francesca D’Antonio Please note that this case study was first published on blogs.ucl.ac.uk/eicah in June 2014. For citation advice, visit: http://blogs.uc.ac.uk/eicah/usingthewebsite. Unlike other ‘objects studies’ featured in the East India Company At Home 1757-1857 project, this case study will focus on a specific ceramic ware pattern rather than a particular item associated with the East India Company (EIC). With particular attention to the contents of Dunham Massey, Greater Manchester, I focus here on the Willow Pattern, a type of blue and white ‘Chinese style’ design, which was created in 1790 at the Caughley Factory in Shropshire. The large-scale production of ceramic wares featuring the same design became possible only in the late eighteenth century after John Sadler and Guy Green patented their method of transfer printing for commercial use in 1756. Willow Pattern wares became increasingly popular in the early nineteenth century, allowing large groups of people access to this design. Despite imitating Chinese wares so that they recalled Chinese hard-stone porcelain body and cobalt blue decorations, these wares remained distinct from them, often attracting lower values and esteem. Although unfashionable now, they should not be merely dismissed as poor imitations by contemporary scholars, but rather need to be recognized for their complexities. To explore and reveal the contradictions and intricacies held within Willow Pattern wares, this case study asks two simple questions. First, what did Willow Pattern wares mean in nineteenth-century Britain? Second, did EIC families—who, as a group, enjoyed privileged access to Chinese porcelain—engage with these imitative wares and if so, how, why and what might their interactions reveal about the household objects? As other scholars have shown, EIC officials’ cultural understandings of China often developed from engagements with the materials they imported, as well as discussions of and visits to China. -

China: Qing Dynasty Porcelain and Global Exchange Pre-Visit

China: Qing Dynasty Porcelain and Global Exchange Pre-Visit Share this background information with students before your Distance Learning session. Grade Level: Grades 9-12 Collection: East Asian Art Culture/Region: China, East Asia Subject Area: History and Social Science Activity Type: Distance Learning WHY LOOK AT PLATES AND VASES? When visiting a relative or a fancy restaurant, perhaps you have dined on “fine china.” While today we appreciate porcelain dinnerware for the refinement it can add to an occasion, this conception is founded on centuries of exchange between Asian and Western markets. Chinese porcelain production has a long history of experimentation, innovation, and inspiration resulting in remarkably beautiful examples of form and imagery. At the VMFA, you will examine objects from a small portion of this history — the 18th century during the Qing Dynasty — to expand your understanding of global exchange in this era. Because they were made for trade outside of China, these objects are categorized as export porcelain by collectors and art historians. Review the background information below, and think of a few answers you want to look for when you visit VMFA. QING DYNASTY Emperors, Arts, and Trade Around the end of the 16th century, a Jurchin leader named Nurhaci (1559–1626) brought together various nomadic groups who became known as the Manchus. His forces quickly conquered the area of present-day Manchuria, and his heirs set their sights on China. In 1636 the Manchus chose the new name of Qing, meaning “pure,” to emphasize their intention to purify China by seizing power from the Ming dynasty. -

Page 1 578 a Japanese Porcelain Polychrome Kendi, Kutani, 17Th C

Ordre Designation Estimation Estimation basse haute 551 A Chinese mythological bronze group, 19/20th C. H: 28 cm 250 350 552 A Chinese bronze elongated bottle-shaped vase, Ming Dynasty H.: 31 600 1200 cm 553 A partial gilt seated bronze buddha, Yongzheng mark, 19th C. or earlier 800 1200 H: 39 cm L: 40 cm Condition: good. The gold paint somewhat worn. 554 A Chinese bronze jardiniere on wooden stand, 19/20th C. H.: 32 cm 300 600 555 A Chinese figural bronze incense burner, 17/18th C. H.: 29 cm 1000 1500 556 A Chinese bronze and cloisonne figure of an immortal, 18/19th C. H.: 31 300 600 cm 557 A Chinese bronze figure of an emperor on a throne, 18/19th C. H.: 30 cm 800 1200 Condition: missing a foot on the right bottom side. 558 A bronze figure of Samanthabadra, inlaid with semi-precious stones, 4000 8000 Ming Dynasty H: 28 cm 559 A Chinese gilt bronze seated buddha and a bronze Tara, 18/19th C. H.: 600 1200 14 cm (the tallest) 560 A Chinese bronze tripod incense burner with trigrams, 18/19th C. H.: 350 700 22,3 cm 561 A tall pair of Chinese bronze “Luduan� figures, 18/19th C. H.: 29 1200 1800 cm 562 A tall gilt bronze head of a Boddhisatva with semi-precious stones, Tibet, 1000 1500 17/18th C. H.: 33 cm 563 A dark bronze animal subject group, China, Ming Dynasty, 15-16th C. H.: 1500 2500 25,5 cm 564 A Chinese dragon censer in champlevé enameled bronze, 18/19th C. -

Antiques-February-1990-Victorian-Majolica.Pdf

if It1ud!!&/ ';"(* ./J1!11L. /,0t£~ltldtiJlR~~~rf;t;t r{/'~dff;z, f!71/#/~i' 4 . !(Jf~f{ltiJ(/dwc.e. dJ /¥ C\-Cit!Ja? /Hc a4 ~- t1 . I. le/. {./ ,...."".. //,; J.(f)':J{"&Tf ,4.~'.£1//,/1;"~._L~ • ~. ~~f tn.~! .....•. ... PL IL Baseball and Soccer pitcher made by Griffen, Smith and Company, PllOeni;'Cville,Pennsylvania. c.1884. Impressed "GSH "in nlOnogram on the bottom. Height 8 inches. The Wedgwood pattern book illustration of the same design is shown in PL Ila. Karmason/Stacke collection; White photograph. PL /la. Design from one of the pattern books of Josiah Wedgwood and Sons, Barlaston, Stoke-on-Trent, England. Wedgwood Museum, Barlaston, Stoke-on-Trent, England. and Company, Josiah Wedgwood and Sons, and majolica.! New designs for majolica ceased to be made George Jones and Sons. From these books one be• in the early 1890's, and production of majolica ceased comes familiar with the style of the maker and comes early in this century. to appreciate the deliberate choice of details that gives The Minton shape books are valuable not only be• each piece its unity. cause they help date the first production of a piece but By 1836 Herbert Minton (1792- 1858) had succeed• also because they show the development of the eclectic ed his father, Thomas (1765-1836), the founder of the and revivalist styles used by Minton artists. The earli• prestigious Minton firm. In 1848 Joseph Leon Fran• est style used by the firm was inspired by Renaissance ~ois Arnoux (1816-1902) became Minton's art direc• majolica wares.Z Large cache pots, urns, and platters tor, chief chemist, and Herbert Minton's close col• were decorated with flower festoons, oak leaves, car• league. -

Cincinnati Art Asian Society Virtual November 2020: Asian Ceramics

Cincinnati Art Asian Society Virtual November 2020: Asian Ceramics Though we can't meet in person during the pandemic, we still want to stay connected with you through these online resources that will feed our mutual interest in Asian arts and culture. Until we can meet again, please stay safe and healthy. Essays: East and West: Chinese Export Porcelain https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/ewpor/hd_ewpor.htm Introduced to Europe in the fourteenth century, Chinese porcelains were regarded as objects of great rarity and luxury. Through twelve examples you’ll see luxury porcelains that appeared in Europe in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, often mounted in gilt silver, which emphasized their preciousness and transformed them into entirely different objects. The Vibrant Role of Mingqui in Early Chinese Burials https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/mgqi/hd_mgqi.htm Burial figurines of graceful dancers, mystical beasts, and everyday objects reveal both how people in early China approached death and how they lived. Since people viewed the afterlife as an extension of worldly life, these ceramic figurines, called mingqi or “spirit goods,” disclose details of routine existence and provide insights into belief systems over a thousand-year period. Mingqi were popularized during the formative Han dynasty (206 B.C.–220 A.D.) and endured through the turbulent Six Dynasties period (220–589) and the later reunification of China in the Sui (581–618) and Tang (618–907) dynasties. There are eleven ceramic burial goods (and one limestone) as great examples of mingqui. Indian Pottery https://www.veniceclayartists.com/tag/indian-pottery/ The essay is informative but short. -

A History of Delftware Delftware Is Tin-Glazed Earthenware, Composed

A History of Delftware Delftware is tin-glazed earthenware, composed of a buff-colored body coated with a layer of lead opacified by tin ashes. It first appeared in the Near East in the 9th century, and then spread through trade to the Mediterranean, reaching South Spain in the 11th century. Delftware appeared in Italy in the 14th century before moving to France and the Low Countries (present day Netherlands, Belgium, and Luxembourg) in the early 16th century. Despite its eastern origins, Delftware was named for the city of Delft, Holland, an area known both for pottery and several Delftware factories. In the 16th century, the Dutch modeled their pottery on the characteristics of Italian pottery. By the 17th century, however, the Dutch controlled much of the trade around Asia, having seized control from Portugal. As a result, Chinese style porcelain became extremely popular in the Netherlands. The factories that produced Delftware began to copy porcelain designs. This practice netted a huge profit after internal Chinese wars disrupted trade between China and the West and reduced the amount of porcelain imported from the east. The great demand for Chinese porcelain led many Dutch to buy Delftware porcelain In 1567 two Flemish potters, Jasper Andries and Jacob Jansen, arrived in Norwich, England to establish a Delftware factory. There was not enough clay in that area of England, however, so the two men moved their factory to London. In the 17th and 18th century other “Low Country” immigrants began arriving in England and established Delftware factories. These factories profited from exporting their products to the colonies in the Americas.